This story originally appeared on The Minnesota Historian, a new local history website from Josh Biber.

Ten-thousand years ago, as the Wisconsin Ice Sheet retreated to the north from Minnesota, it left behind an insurmountable amount of debris and melting ice chunks. The glaciers carved deep gouges in the land, thus creating many bodies of water in Minneapolis. However, the City of Lakes once had nearly a dozen more bodies of water than today. Several of the city’s lakes and ponds have been lost in the process of industrialization and urbanized growth.

In 1883, the Minneapolis Park Board was created. In the 50 years that followed, the board worked tirelessly to build the Grand Rounds National Scenic Byway, parkways, and chain of lakes systems. Most of the parks we know today were built during this period of time, while the ongoing work of dredging and reclaiming the chain of lakes was accomplished by 1911.

Not all lakes and bodies of water were treated equally in Minneapolis. Where Minnehaha Creek was preserved as pristine parkland for the city, Bassett Creek was entombed in a drain pipe underneath the North Loop. Where the chain of lakes were heralded as the watery jewels of the City of Lakes, several other lakes were considered truculent or otherwise impeding Minneapolis's development.

These undervalued lakes were ultimately disregarded, polluted, and leveled by the hands of city employees to make way for urbanization in the early years of Minneapolis. It’s likely that you’ve walked on or even lived by these lost lakes that earlier settlers of Minneapolis once swam or fished on.

Blaisdell Lake

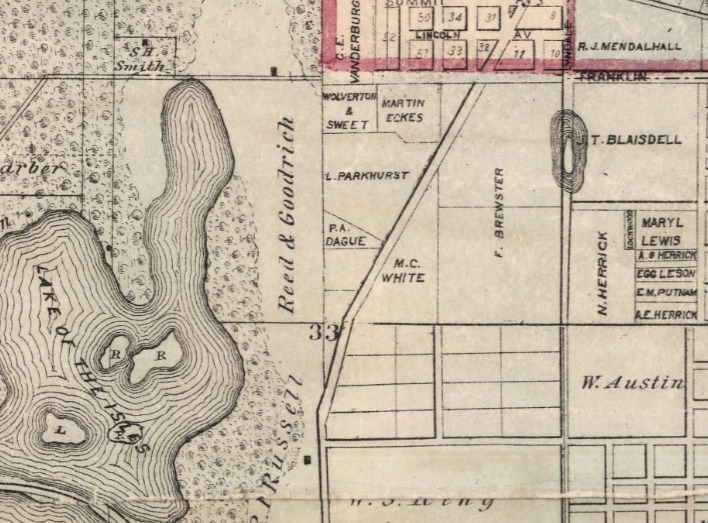

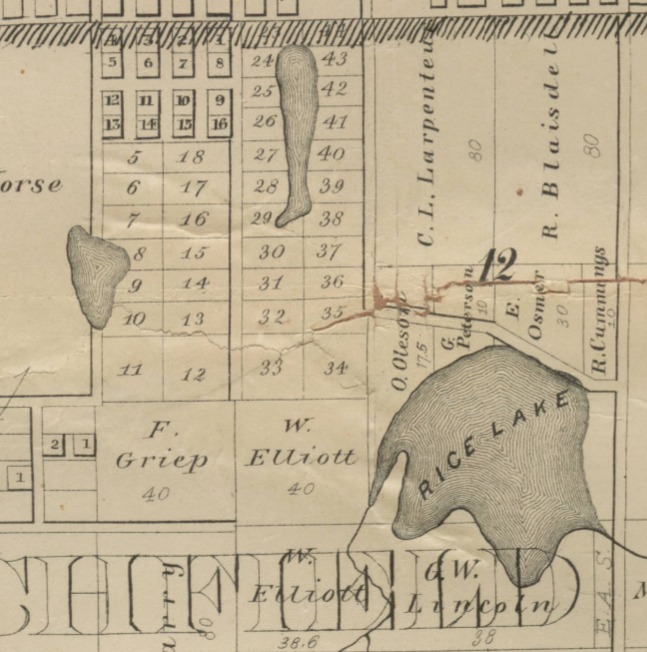

In 1855, early Minneapolis resident John Blaisdell built a log cabin on a small bluff near the present-day intersection of Nicollet Avenue and 24th Street, overlooking a small but deep lake southwest of downtown. Blaisdell constructed a carriage road to the lake on what would become 24th Street. At the time, this plot of land was considered the countryside, and Blaisdell found peace and refuge on the fringes of the city.

Named after its first Euro-American resident, Blaisdell Lake was a popular location for swimming and ice skating in the 1870s, as downtown Minneapolis, located just over a mile away, became heavily populated. Its short distance from the city’s epicenter made Blaisdell Lake a popular getaway. Its shores were roughly bordered by present day 22nd Street to the north, 25th Street to the south, Harriet Avenue to the east, and Lyndale Avenue to the west.

Blaisdell Lake was about 40 feet deep and covered 20 acres. It became a victim of the housing boom in the Whittier neighborhood in the late 1880s. By 1890, the city needed to extend Lyndale and Harriet Avenues to the south. The lake was filled in so as to not impede those avenues from running in a tidy north-to-south direction. With the lake bed filled, the city sold the land for development.

In 1936, the lake was reminisced upon by two early Minneapolis residents, Frank Lewis and George Porter. The two recounted memories of skating and swimming on the lake, having picnics under the canopy of trees near the shore, and relocating some trace evidence of old trees that once dotted the shore. Porter recalled, “It was really a country resort of the old days, but I don’t believe anyone ever caught a fish in [Blaisdell Lake]… I never saw any other water containing so many leeches.”

The lake itself is long gone, but that doesn’t stop water from flowing into its old basin. When larger storms rear their ugly head over this section of south Minneapolis, Blaisdell Lake emerges again as storm runoff flows into the old lakebed, frequently flooding local businesses and homes.

Sandy Lake

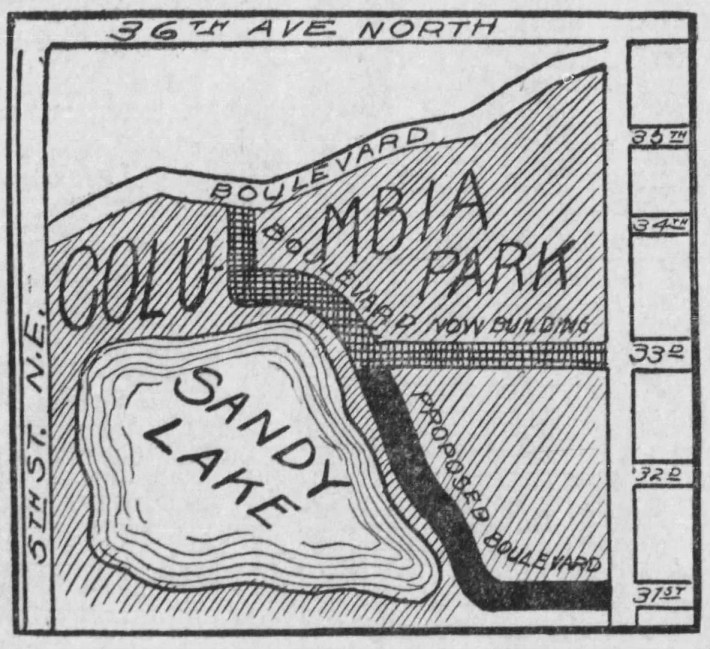

“Sandy Lake is the place on which the people of northeast Minneapolis have an eye," the Minneapolis Journal wrote in 1905. "It suggests to them a beautiful vista of pleasure and enjoyment—not in its present state by any means—but perhaps some time after the hand of cultivation has taken hold of it. In a district where water is at a premium and where lakes and rivers are conspicuous by their absence, a lake counts.”

Sandy Lake was an imposing sheet of water in the far northeast reaches of Minneapolis. The lake was spring fed, but its size was largely dependent on rainfall, frequently waxing and waning between 40 to 75 acres. In 1905, the city was working with the Minneapolis Park Board to improve Sandy Lake. Ideas were proposed to build a small network of boulevards to circule a portion of the lake, as well as dredging operations to deepen the lake for swimming. The big idea was that with enough money and effort, Sandy Lake would become a suitable rival to the chain of lakes in southwest Minneapolis.

However, these ideas were short-lived. By 1914, the lake had mostly dried up. The Soo Line Railroad Company was first to take advantage, purchasing and vacating several blocks for an imposing rail yard and roundhouse to the south and west of the lake. Seeing that reviving the lake was a steep uphill battle, the city graded and filled most of the lakebed, turning the new land into an athletic field and playground. This change was met with little pushback from the nearby residents, as this area of the city was in desperate need of more parkland.

After a few years as an athletic field, the land that was once Sandy Lake was redeveloped into Columbia Golf Course. The course first opened in 1919 as a six-hole course, then expanded to nine holes by 1920. By 1923, the course saw its final expansion to a full 18-hole regulation golf course. There are very few signs that this section of Minneapolis was once home to Sandy Lake, though even today some of the deeper portions of the original lakebed remain as water hazards on the course.

Long John Pond

Just to the northeast of Thomas Edison High School lies the old lakebed of Long John Pond. This body of water stretched roughly two blocks long and a block-and-a-half wide. Long John Pond was a popular winter recreation area with ice skaters and ice fishers until about 1905 when, after years of illegal dumping of refuse and rubbish into the pond by surrounding establishments, it became an eyesore. The city sought to resolve the issue by constructing 22nd Avenue through the middle of the pond. Subsequently, the pond was drained for development. In 1906, the remains of the pond were filled in to create Jackson Square Park.

Removal of the pond was widely opposed by the neighborhood. Many surrounding residents felt that there were more pressing needs and improvements the city needed to take care of before the conversion of Long John Pond into parkland. The general consensus? That it would have been more worthwhile to clean the pond of its detritus. Despite the large push to keep Long John Pond, the city redeveloped the land into a small park.

A 1907 Minneapolis Journal article reminisced on Long John Pond. On a search for the appellation of the pond, a neighborhood policeman was asked who Long John was. “I guess he was one of these tall, slim fellers, maybe," he replied.

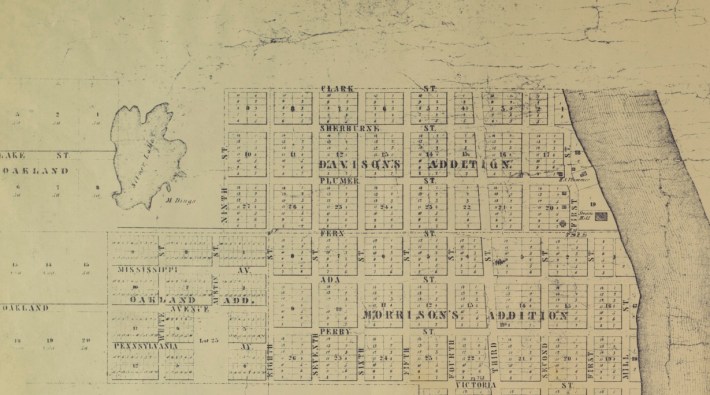

Silver Lake

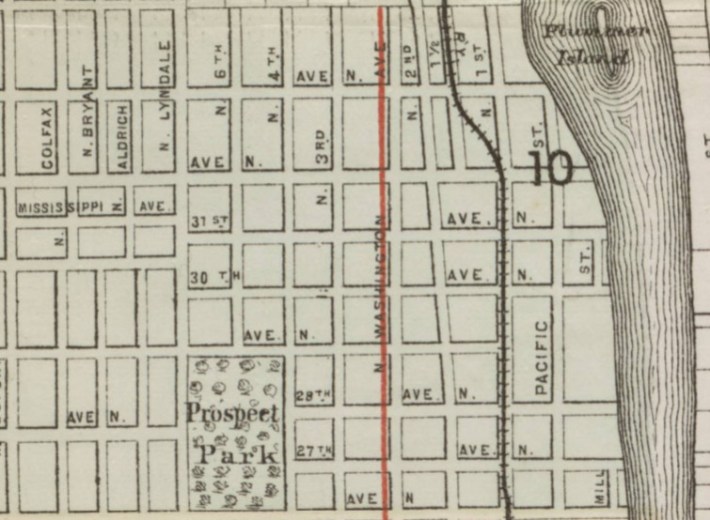

Silver Lake was about a block long, centered on 33rd Avenue North between Colfax and Dupont Avenues. After extensive searching, I was unable to find any historical context about the lake, or when it was possibly filled in. Newspapers as early as 1889 were selling lots in the Silver Lake Addition of north Minneapolis. Therefore, it can be presumed the lake was filled in by then.

The first map below depicts Minneapolis circa 1861; Silver Lake sits unbothered by the encroaching development of the prairies of northern Minneapolis. However, the 1888 map in the middle depicts Silver Lake over-imposed by a street grid. By 1889, Silver Lake no longer appears on the official map of Minneapolis, as seen on the third map. One can deduce that between 1889 and 1890, Silver Lake was leveled for property development.

Silver Lake paints a picture of the shortcomings of historical documentation. Things that seem inconsequential at the time—say, filling in a small lake for the development on the fringes of a frontier city—are entirely lost to history if not captured in writing. We know there was a Silver Lake, but, sadly, we don't know its fate or the stories of those who visited it.

Oak Lake and Hoag’s Pond

It’s hard to imagine that the location of the Minneapolis Farmers Market was once a small lake, and even harder to imagine that the surrounding industrial park used to be a regal neighborhood of Victorian- and Queen Anne-style homes.

Oak Lake was a small pothole lake immediately to the west of downtown. Another, smaller body of water named Hoag’s Pond was situated a few blocks to the east of Oak Lake, within the outfield of present-day Target Field.

Hoag's Pond was named after Charles Hoag, the first schoolmaster of Minneapolis. Hoag's Pond was filled in during the development of the Hoag Addition (bordered by North Third and North Sixth Streets, Hennepin Avenue, and North Fifth Avenue in the North Loop) of Minneapolis between 1857 and 1873. Unlike the other lakes, Hoag's Pond was not filled in by the Minneapolis Park Board.

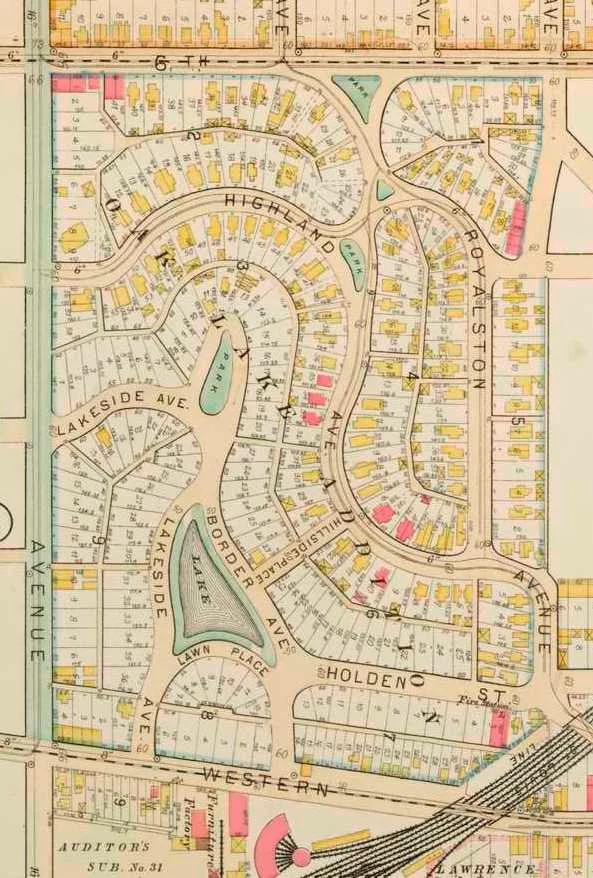

Surrounding Oak Lake was the Oak Lake Addition, an early upper class neighborhood platted in 1873. The Oak Lake Addition was confined by Glenwood Avenue to the south, Sixth Avenue to the north, a railyard and Royalston Avenue to the east, and Lyndale Avenue to the west. Curiously, there are some streets in this area today that pay homage to Oak Lake, à la Oak Lake Avenue and Lakeside Avenue.

Oak Lake Addition was an enticing neighborhood for the Minneapolis elite in the 1870s and early 1880s. Several high profile families moved to the new neighborhood. Leroy Buffington, the man who patented the “cloudscraper” (known today as skyscrapers), also called the Oak Lake Addition home.

However, things quickly stagnated at Oak Lake and the surrounding neighborhood. One of the Park Board’s first actions was to establish an attractive new park around Loring Pond, just over a half-mile to the south of Oak Lake. Thus, Loring Park (then Central Park) quickly eclipsed Oak Lake in terms of beauty and accessibility. Loring Park was both closer to downtown and easier to get to. To reach Oak Lake, travelers had to travel beyond the Great Northern Rail Yards, which posed as a man-made barrier separating the Oak Lake Addition from the rest of downtown. To further complicate matters, Oak Lake was close in proximity to Bassett Creek; the creek’s putrid scent frequently wafted over the surrounding neighborhood, dissuading residents from visiting the little lake.

By the early 1910s, the unattended Oak Lake was a languid body of water ripe with algae and mosquitoes. In addition, several of the prominent families who lived in the neighborhood had relocated to more valuable properties in Kenwood and Lowry Hill, and their old properties in the Oak Lake Addition fell into despair. The Park Board filled the lake in 1915 and built tennis courts on the ground where the lake once was. By 1936, the Minneapolis Park Board conceded the Oak Lake land to the city to develop a farmers market.

In the span of several decades, Oak Lake and the surrounding neighborhood had evolved from an upper-class neighborhood, to forlorn abandoned properties, to a farmers market and surrounding industrial park.

Stocking Lake and Bancroft Marsh

Named after its sock-like shape, Stocking Lake was located at 19th Avenue South between 39th and 42nd Streets (where present day Sibley Field is located). Stocking Lake was the lowest point in the surrounding valley where storm runoff would frequently congregate to form a small pond after heavy rainfall. With nowhere for the rainfall to drain, the stagnant water of Stocking Lake was a breeding ground for flies and mosquitoes. In 1923, the Park Board leveled and graded Stocking Lake to create Sibley Field.

Bancroft Marsh was another low point in the surrounding prairie to the west of Stocking Lake. With heavy rainfall, the marsh would fill with water to create a sizable pond. In the 1920s, Bancroft Marsh was filled and leveled with dirt excavated from the nearby Sears Building construction project on Lake Street and Chicago Avenue. For several years afterward, the former marshland was used as a dumping site until the land was purchased for the development of small rambler homes in the 1950s. Having been built on former marshland, the collection of homes experienced frequent flooding issues.

After decades of complaints from residents, the city purchased and razed the homes on the block to build an underground waste-water pumping station commissioned by the Minneapolis Department of Public Works in the late 1980s. The land was then converted into Bancroft Meadows, a partially wooded and open space frequented by dog walkers.

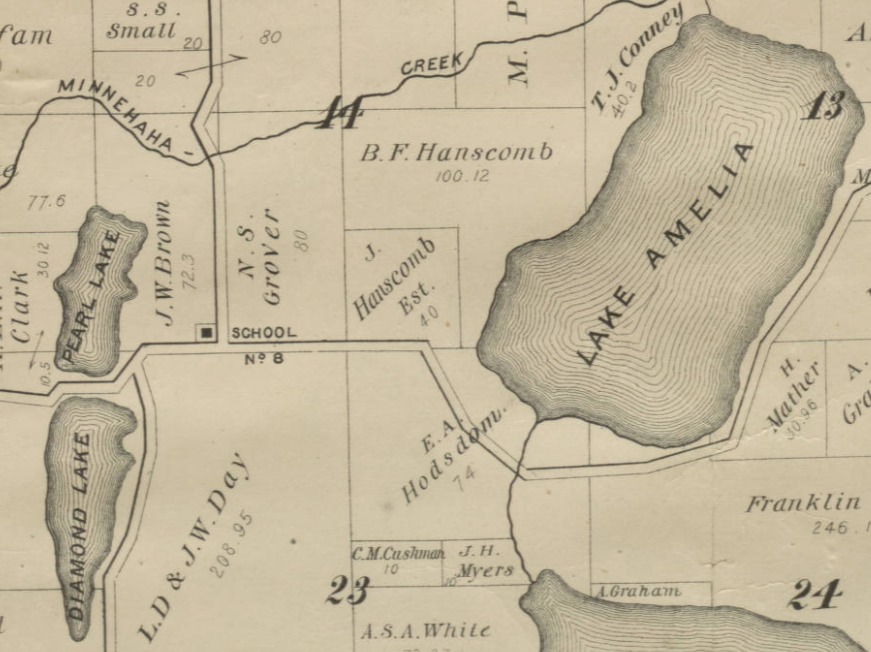

Pearl Lake

Pearl Lake was the twin sister to the north of Diamond Lake. Pearl Lake was a shallow, boggy, 29-acre basin. The lake was converted to a park when it was filled during a 1936 Public Works Administration project in conjunction with the Minneapolis Park Board.

During this project, the peaty layer of lakebed was removed, dirt excavated from the runway development project at the Minneapolis-St. Paul Airport filled in the lakebed of Pearl Lake, and the layer of peat was placed atop the dirt to form Pearl Park.

Richfield Mill Pond

The Richfield Mill Pond was a man-made dammed backup of water on Minnehaha Creek from the Richfield Mill near present-day Lyndale Avenue and Minnehaha Creek Parkway. This pond encompassed Lyndale Avenue all the way to the southeast shore of Lake Harriet, covering over 30 acres of land. Historical recounts surmise that the Richfield Mill Pond was approximately 20 feet deep, with good waters for fishing.

Richfield Mill Pond and the subsequent flow of Minnehaha Creek in this area was corrected in 1892 when the mill’s dam was torn out by the Washburn family to build the Lyndale Avenue bridge over Minnehaha Creek, connecting Richfield to Minneapolis.

Todd’s Pond

Todd’s Pond was a three-acre, 20-foot-deep body of water. The pond was roughly a block long between North 17th and 18th Avenues, bordered to the east and west by Fremont and Girard Avenues respectively. Todd’s Pond was adored by many community members in the late 1800s for its pristine conditions for wintertime activities such as ice skating and ice fishing. To others, the defiant pond was an issue, as it frequently breached its banks and flooded the surrounding properties. After the particularly wet spring of 1888, community members met to discuss the future of the pond. Residents who lived directly beside Todd’s Pond wished for the pond to be filled, thus relieving their properties of the frequent flooding.

It wasn’t until 1915 that these wishes were met. With the expansion of North High School’s athletic teams, the school was in need of an athletic field. Subsequently, the nearby Todd’s Pond was chosen as the preferred location for the new field. The pond was leveled and replaced with the first iteration of North High School’s football field. After the football field experienced endless flooding issues throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the field's drainage was substantially improved upon in 1937 and renamed Hobbs’ Field in honor of W. Hobbs, a former North High principal.

The below images first depict an 1888 headline highlighting the concern of flooding at Todd's Pond. The second headline unveils the new Hobbs' Field at North High School in 1937.

The Impact of Our Lost Lakes

In the first 60 years after Minneapolis’s founding, the City of Lakes lost 11 bodies of water. Under the jurisdiction of the Minneapolis Park Board, several of these ponds and lakes were drained, grass was planted, and parks were created. The newly created parks were but a small silver lining, as the removal of these waters meant the destruction of valuable centers of biodiversity.

Besides the wide selection of microorganisms and flora, these bodies of water provided habitats to mammals, fish, and several species of birds. However, to our early Park Board presidents, wetlands were mostly considered inconvenient places where mosquitoes thrived.

In Minneapolis’s brief modern history, all lands and bodies of water were taken by white settlers from the Mdewakanton Dakota and brought into an expanding agricultural, industrialized American empire. In the process of being integrated into a new regime, several Minneapolis lakes faced the subjective reckoning of the Minneapolis Park Board. When the Park Board struggled to find solutions for these lakes, they simply chose to level them.

In limbo between the intersection of humanity and nature, the life of these bodies of water became entwined with the ethos of capitalism, industrialization, and manifest destiny. The thought that we can sacrifice one environment to develop another is not unique to our lost lakes. However, the sacrifice of these lakes was anything but inevitable. Rather, these abdications were a byproduct of how those in power desire society and landscape to be constructed.

Sources:

- “Old Willow Tree on Harriet Avenue Marks Shoreline of Lake Blaisdell” The Minneapolis Tribune, February 2, 1936. P. 6.

- “Site of old Blaisdell Lake, Minneapolis” MN Historical Society. 1936. http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/largerimage?irn=10104184&catirn=10722101&return=

- Cook. R. F. “Map of St. Anthony and Minneapolis” 1861. http://geo.lib.umn.edu/historicmn/minneapolis.pdf

- Wright, George Burdick, 1835-1882. Map of Hennepin County, Minnesota. 1873. Minnesota Historical Society, collection.mndigital.org/catalog/mhs:865 Accessed 18 Aug. 2022.

- “Complete Boulevard Around Sandy Lake” The Minneapolis Tribune. June 16, 1905. P. 11.

- “Want to use Sandy Lake” The Minneapolis Journal. June 2, 1905. P. 19.

- “Must Long John’s Name Be Dropped?” The Minneapolis Journal. December 16, 1907. P. 9.

- Smith, David C., “Lost Minneapolis Parks: Oak Lake, Two Ovals and Two Triangles” Minneapolis Park History. May 1, 2022. https://minneapolisparkhistory.com/2011/05/01/lost-minneapolis-parks-oak-lake/

- Froiland, Samuel. “Making the Minnehaha: The Reengineering of a Creek and the Creation of an Envirotechnical System” May, 2019. https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/206186/Froiland_umn_0130M_20251.pdf;jsessionid=628DC0BF56DA347F51B10F47FCE27591?sequence=1

- Smith, David C. “Sibley Field Flattened 1923” Minneapolis Park History. August 1, 2012. https://minneapolisparkhistory.com/tag/sibley-field/

- Smith, David C. “Is That a Lake?” Minneapolis Park History. December 7, 2012. https://minneapolisparkhistory.com/tag/pearl-park/

- Busch, Robert C. “Back of an Apartment House at the Edge of the Former Lake Blaisdell” Hennepin County Library Digital Collections. 1936. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/MplsPhotos/id/11064

- Buchta, Jim. “Spotlight on Bancroft Neighborhood” Star Tribune. November 16, 1996. P. H7.

- Felien, Ed. “Find Bancroft Meadows Down in the Valley” Twin Cities Daily Planet. August 8, 2010. https://www.tcdailyplanet.net/find-bancroft-meadows-down-valley/

- Davison, C. W. “Davison's Directory Map of Minneapolis, Minn.” Hennepin County Library Digital Collections. 1883. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll17/id/138/rec/21

- “Plan of the City of Minneapolis and Vicinity” Hennepin County Library Digital Collections. 1874. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll17/id/59/rec/7

- “Houses and Duplexes on Royalston Ave” Hennepin County Library Digital Collections. May 13, 1930. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/CPED/id/10834

- “Graft Charge Over New Park” Minneapolis Daily Times. July 12, 1905. P. 3.

- PEARL LAKE https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/mhs:865#?c=&m=&s=&cv=8&xywh=51%2C359%2C2122%2C1488

- "Minneapolis Municipal Market" Hennepin County Library Digital Collections. September 2, 1937. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/CPED/id/10205

- Demolition of Houses on the Site of the Minneapolis Municipal Market" Hennepin County Library Digital Collections. 1936. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/CPED/id/17345