The History of a Hidden, Toxic Creek That Still Flows Beneath North Loop

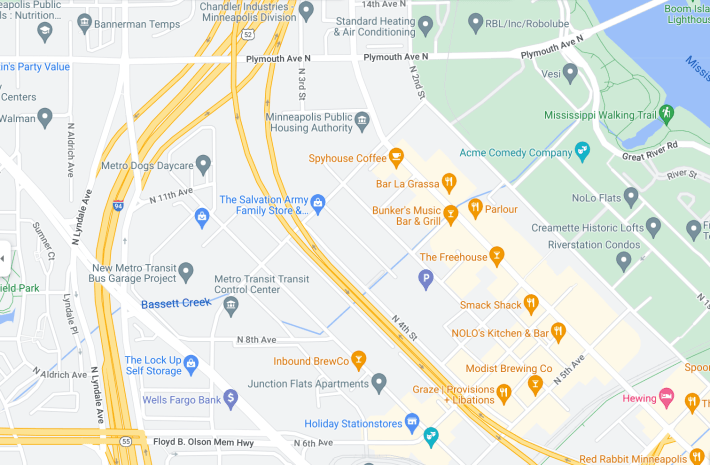

You've seen Bassett Creek on Google Maps, but the 'truculent little river' was hidden deep below Minneapolis streets over 100 years ago.

11:38 AM CDT on August 3, 2022

Where Bassett Creek exits into the Mississippi River.

This story originally appeared on The Minnesota Historian, a new local history website from Josh Biber.

If you pan through the North Loop on Google Maps, you'll see that a pair of odd, blue streaks irregularly jog through the area. Your initial thought might be, “Well that’s not right, I can’t think of any stream in the North Loop.” And you'd be right—there isn’t a creek in the North Loop. But there is one below the North Loop.

Bassett Creek is an ancient water catchment with a modern story to tell. Flowing 12 miles from its source at Plymouth's Medicine Lake, the creek meanders through backyards, parks, and golf courses in the western suburbs. Once the creek reaches the city, however, it quickly vanishes into a gargantuan tunnel where it travels deep underneath roadways, parking lots, buildings, and railways. Fans enjoying a Twins game on a weekend afternoon are none the wiser that there’s a creek flowing through a deep, dark tunnel dozens of feet underneath them.

Bassett Creek is an overwhelmed urban waterway unable to cope with so many humans. What was once a place of vegetation, mud, rocks, and biodiversity is now one of impenetrable surfaces feeding a network of sewers and drains. No Minnesotan creek has suffered as much from urbanization.

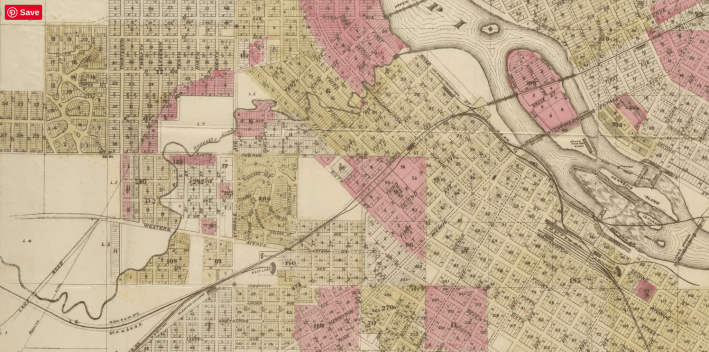

The creek was named after settler Joel Bean Bassett, who worked on his farm and sawmill at the creek’s confluence with the Mississippi beginning in 1852. By 1856, the city began to develop a street grid near Bassett’s property that would become the present day North Loop. Bassett, seeing this as a moment of opportunity, sold much of his property to be developed into city lots prime for industry.

Bassett Creek: It's No Minnehaha

Early in Minneapolis’s history, Bassett Creek was designated as the city’s other creek. Minnehaha was more idyllic, with its beloved Falls and Longfellow Glen. The falls alone ensured that Minnehaha Creek was destined as parkland for citizens to enjoy for generations.

Bassett Creek did not receive the same love. As residents and industry began popping up near its banks in the late 1800s, the creek suffered. By 1876, Bassett Creek was hazardous. Runoff of oils, fats, chemicals, and effluent from the several factories of the Warehouse District all found their way into Bassett Creek’s watershed. The common joke was that if you fell into the creek, you’d dissolve. Individuals walking through the Warehouse District knew they were approaching Bassett Creek when they could smell its sickly sweet perfume.

The city planned to tidy up the creek with cement banks. This took several decades to initiate, with an 1882 article stating that the creek was “a prolific source of filth and poison… the suggestion that a solution of the difficulty might be found in turning the creek into a sewer, the outlet of which should be below [St. Anthony Falls], is certainly worthy of consideration.”

When the Minneapolis Park Board came into existence in 1883, it took interest in Bassett Creek. Horace Cleveland, the Park Board president at the time, stated:

The region traversed by Bassett’s creek is one which threatens danger to the health of the future city, and its proper treatment is a problem that demands early attention. No one has said anything to me in regard to it, and it was only as I have crossed it at one or two different points that I have had an opportunity to observe it. I venture to make only one suggestion in regard to it, which is that the risk of malaria from it will be greatly increased by the construction of causeways across it at the points where it is crossed by streets, as the valley between every two streets would thus be converted into a deep pit, impervious to the air, whereas if bridges are used, the winds would still have free passage up and down the valley.

(Correction: Cleveland is considered "the father of our parks system," Park Board archivist/records specialist Angela Salisbury tells Racket, though he never held an official leadership role with the agency; Charles Loring, the first-ever Park Board president, had just earned the top title in '83.)

Several ideas were floated to counter the city’s suggestion to tunnel the creek. Real estate investor Louis Menage brought forth a plan to route the creek across a swath of land he owned to the west of Washington Avenue so he could build houses there. However, most residents that once lived near Bassett Creek had already departed to areas away from the noise and pollution of the Warehouse District. Even Bassett himself had long left the banks of the creek named after him, relocating to a home on Nicollet Island in 1870.

Conservationists advocated for the diversion of Bassett Creek’s course into the chain of lakes. The community largely backed this idea; a 1905 Minneapolis Journal article, "Getting Rid of a Nuisance," suggested that, in the drier summer months, the addition of Bassett’s water flow into the chain of lakes would guarantee a steady stream at Minnehaha Falls, “relieving everyone of the Bassett Creek problem.” The diversion would cut off the creek’s flow into the Warehouse District, thus “suppressing this truculent little river” from further pollution and flooding in the city’s industrial center.

But this plan never moved beyond the suggestion phase. Bassett Creek continued to be a problem for the city that needed sorting out. A 1906 article concluded that “[eliminating] Bassett Creek is not an easy matter.” As it turned out, they were right. Eliminating Bassett Creek wasn’t an option, but building over the creek was.

In 1908, the city began to tunnel the creek at its confluence with the Mississippi; by 1912, the entombment through the Warehouse District was all but complete. Roughly 60 years after the city of Minneapolis was born, Bassett Creek had transitioned from a peaceful flowing body of water to a polluted sewer buried 80 feet underground.

Bassett Creek's Future: Now What?

Over the last 110 years, there have been countless plans for restoration and reclamation. There have been plans to daylight the creek, plans to clean it from pollutants, plans to straighten its flow, plans to divert it, and plans to turn portions of its path into storm retention ponds.

Of these, only two public reclamation projects for the section of Bassett Creek within Minneapolis ever came to fruition. The first was in 1934, when the Fruen Milling Co. donated a dozen acres of land to Theodore Wirth Park. The Works Progress Administration hired hundreds of individuals to tidy up the creek and straighten its channel north of Glenwood Avenue.

This public works project was not without issues. A culvert connecting the straightened channel with the original creek bed was built incorrectly, and the water had no place to go. A nine-foot-deep sandy swimming hole has now become a shallow eutrophic pool where algal blooms are a common occurrence. For nearly 100 years, this old creek bed has been a stagnant body of water, unable to flow through the culvert.

The second reclamation project for Bassett Creek occurred in the 1990s. The Sumner-Field neighborhood, located just west of Interstate 94, contained a low-income housing project that had been built in the mid-20th century. This housing, built atop unstable soils on Bassett Creek’s original course, ultimately faced severe foundational issues and continuous flooding. This was exacerbated by runoff from the surrounding freeway and impermeable surfaces that couldn’t flow into the wetlands that once surrounded this portion of the creek.

Over the course of several years and several lawsuits, large areas of this neighborhood were razed, and parts of Bassett Creek and the surrounding wetlands were retrofitted to see daylight for the first time in over half a century. Today, Heritage Park has replaced Sumner-Field.

The last 300 yards of Bassett, before it vanishes into the tunnel just past Van White Memorial Parkway, is where the creek is sickest. It's designated as a Superfund site, and toxic metals and waste have seeped into the water from a nearby dump and impound lot.

Not long ago, it wasn’t uncommon to find large debris—trash bags, shopping carts, tires—in this section of the creek. Today, most of the larger detritus has been removed, though smaller waste items remain: soda bottles, beer cans, food wrappers, and the occasional errant golf ball from one of the upstream golf courses.

Bassett’s path of least resistance has rapidly changed over the years at the hands of humans. Fresh water becomes a reason to make camp, camps become settlements, settlements become villages, and, eventually, a city. Cities spur development and industry, and industry pollutes the surrounding land and waters. That’s where Minneapolis finds itself today: stuck with a problem hundreds of years in the making. Meanwhile, St. Paul is working to daylight the once-tunneled Phalen Creek—perhaps Minneapolis can learn a thing or two from how this goes.

Sources:

- “Minnesota Historical Aerial Photographs Online” WN-9-783. July 26, 1937. https://geo.lib.umn.edu/Hennepin_County/y1937/WN-9-783.jpg

- “Getting Rid of a Nuisance” The Minneapolis Journal, May 5, 1905. P. 20.

- Stamps, David. “The Hiding of Bassett Creek” Star Tribune, September 29, 1985. P. 18.

- Ek, Trinity. “Hidden Waterways: Bassett Creek” Open Rivers, Spring 2021. https://openrivers.lib.umn.edu/article/hidden-waterways-bassett-creek/

- Smith, David. “The Myth of Bassett’s Creek” Minneapolis Park History, November 27, 2011. https://minneapolisparkhistory.com/2011/11/27/the-myth-of-bassetts-creek/

- Hart, Chas. H. Davison's Pocket Map of Minneapolis, Minnesota. 1882. Hennepin County Library, James K. Hosmer Special Collections Library, collection.mndigital.org/catalog/mpls:252 Accessed 2 Aug. 2022.

- Rainville Jr., Michael. "Bassett's Creek" Mill City Times, June 28, 2020. http://millcitytimes.com/news/bassetts-creek.html

- Johnson, Daryl. "BassettCreek_TheTunnel" July 8, 2019. https://amaliatulkki.com/bassettcreek_thetunnel/

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Racket

Barnard College Demonstrates Commitment to Free Expression by Suspending Isra Hirsi for Protesting

Plus school district drama, another union Starbucks, and Lake Chipotle 2.0 in today's Flyover news roundup.

Meet David and Goliath: Best Friends, Minneapolis Sidewalk Celebrities

Cities thrive on characters, and these matching buddies are getting noticed all around town.

My MSPIFF So Far and Everything That’s on the Big Screen Right Now

Pretty much every movie you can catch in Twin Cities theaters this week.

Soon You Can Repair Your Computer in MN Without Apple’s Permission

Step aside, planned obsolescence: This July, a new state right-to-repair law will make fixing electronics easier.

MN GOP Lawmaker: Do You Want a House or Do You Want Capitalism?

Plus weed party woes, Clark loved the Lynx, and a safe driving tip in today's Flyover news roundup.