For years, I've been haunted by a bygone store at the Mall of America: BareBones, which sold (you guessed it) scientifically accurate replica bones. Mentions occasionally pop up in MOA anniversary blog posts, and there are vague recollections on Reddit, but I wanted the details. Who was behind it, how long was it in business, and... why bones?

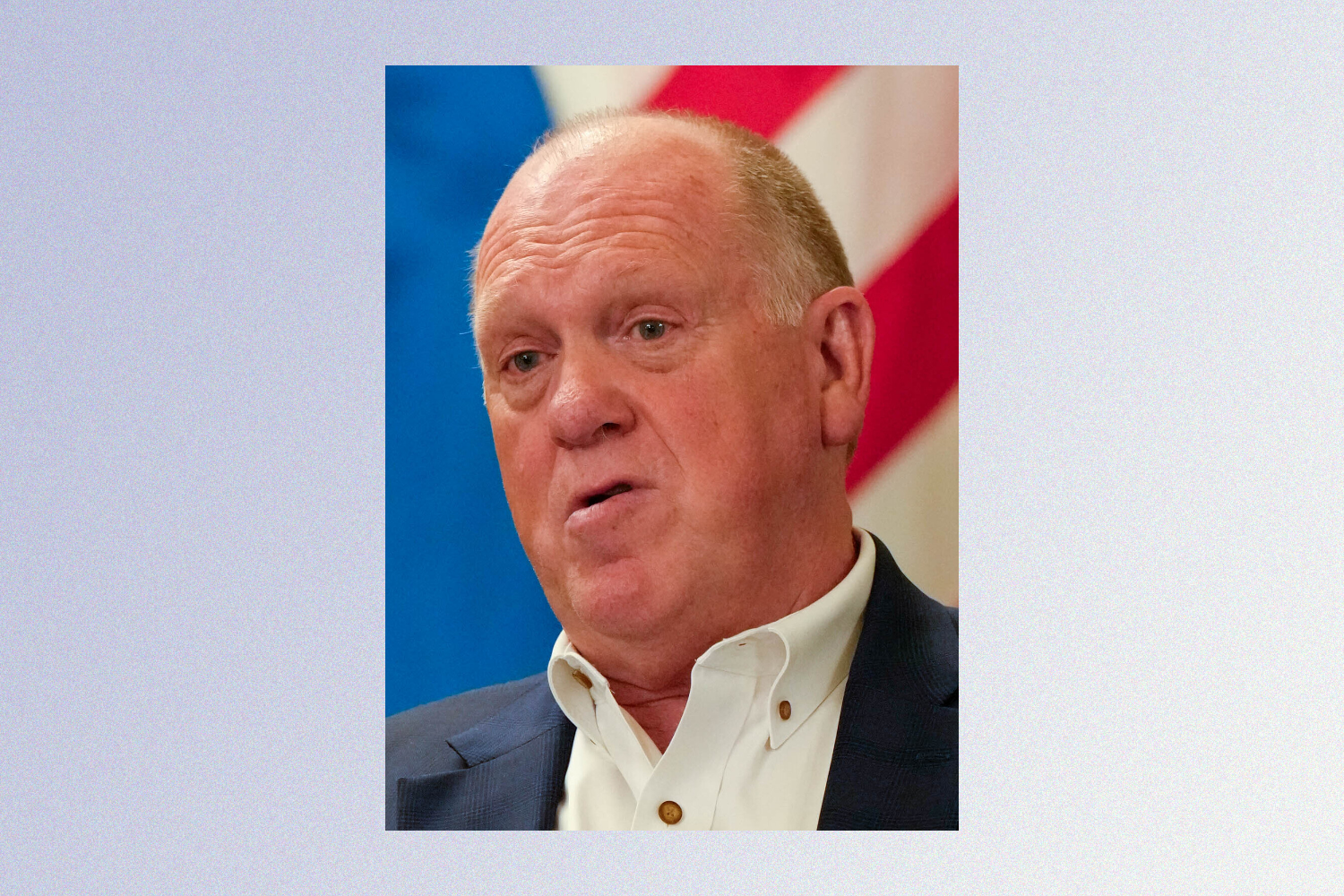

“BareBones was just a sliver of what the business was overall,” erstwhile owner Marshall Cordell tells me. Cordell purchased the Anatomical Chart Company in 1970 and expanded the business into human bones, primarily selling to medical professionals via catalog. After India (his primary supplier) banned the export of human remains in 1985, a Gizmodo profile notes, Cordell became a major player in the replica bones business. He leaned into the burgeoning Halloween industry, opening BareBones stores in a couple Illinois malls, as well as a franchise in Japan.

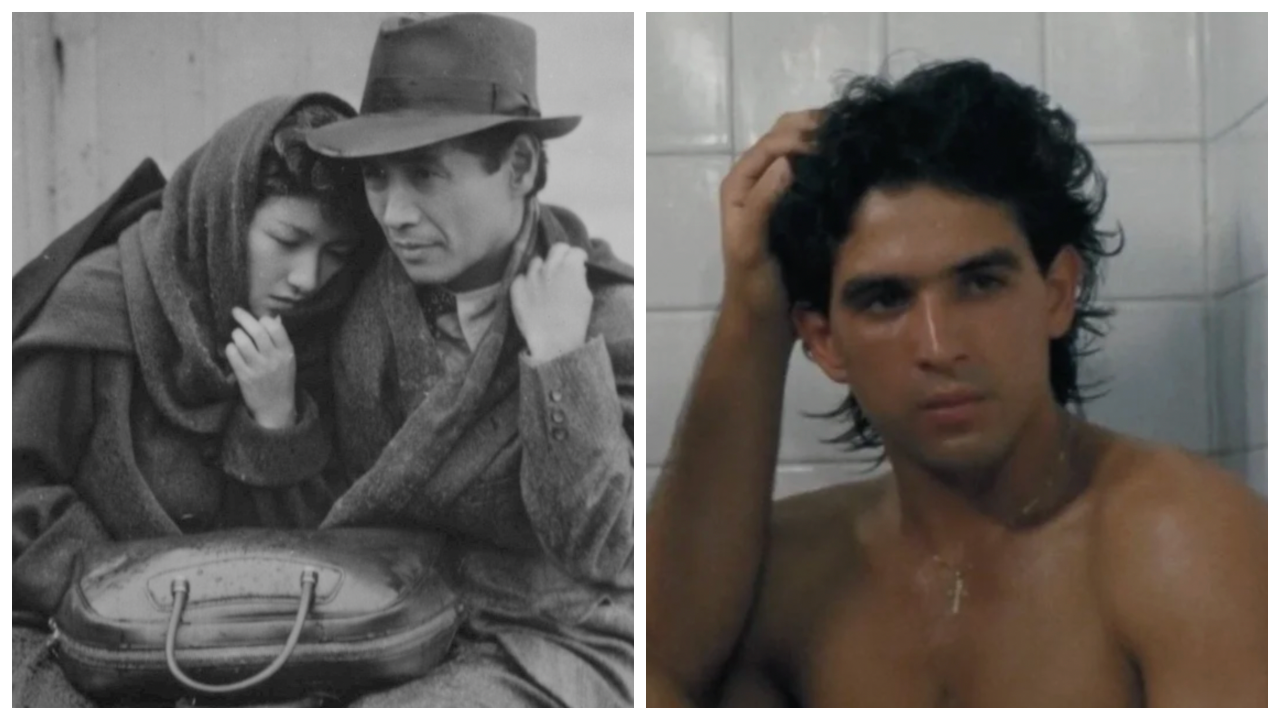

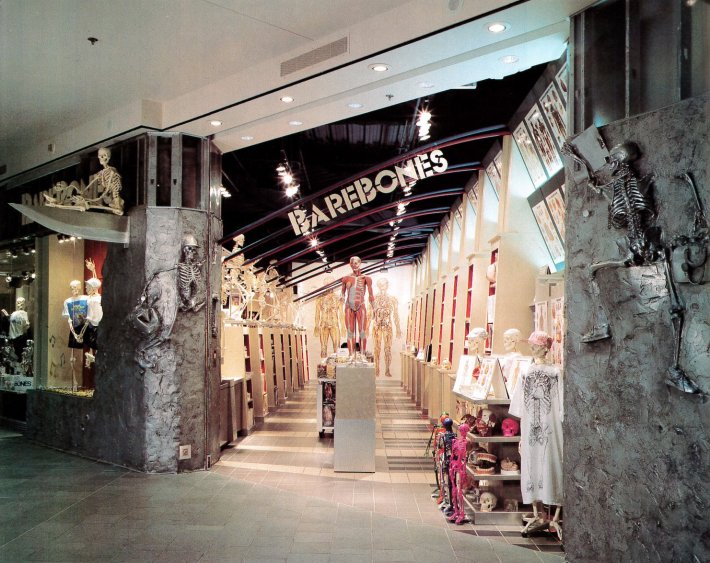

BareBones was an original tenant when the Mall of America opened in 1992, located on Level One North near Nordstrom. In lieu of a traditional sign, a life-sized skeleton perched atop an enormous knife blade jutting from the wall. The entrance was framed by skeletons embedded in the walls, one wearing a baseball cap and another with a stethoscope dangling from its neck. The effect is reminiscent of memento mori carved into Christian tombs—skeletons intended to remind the faithful of their impending demise.

That striking facade was designed by The Kubala Washatko Architects, which specialized in retail clients in the 1980s and 1990s. “We did all the weird stores,” says Vince Micha, the project architect. “We were always doing the different spin and the unexpected.”

The store interior evoked a rib cage, with bone-colored shelves and slender blue and red arches representing veins and arteries. “It was part theater, part anatomical correctness, and part retail,” says Micha. “[We were] making it so there was just enough curiosity that you would draw somebody inside to discover more.”

Once inside, customers discovered many more skeletons, ranging from full-scale replicas to miniature desk-sized models. BareBones also stocked anatomical charts, replica organs, books, educational toys, and novelty items like a color-your-own-anatomy nightshirt. A gelatin mold modeled from an actual human brain was a big seller, Cordell recalls. “It was just really weird, goofy stuff,” he says.

“We have everything from… a $3 keychain to a $3,000 anatomical model,” says Katie Malone in a WCCO 4 News segment covering mall’s opening. (At the time, Malone was married to Cordell and handled the retail side of the business; she didn’t respond to my requests for an interview.)

“It was just so different from any other store, because it's skeletons all over the place,” says Lisa Stockert, the blogger behind Twin Cities Frugal Mom, who recalls visiting BareBones with her friends as a teenager, as well as other offbeat MOA retailers like Hologram Land and Starbase Omega. “[BareBones] was part of the whole ‘Let's go look at weird stores together,’ and that's all we did—we didn't buy a whole lot!”

One customer who did buy a lot? Kurt Cobain. While Nirvana was recording In Utero at Pachyderm Studios in Cannon Falls, Lori Barbero of Babes in Toyland took Cobain to BareBones. “It was my favorite store out there [at the Mall of America], and I knew that Kurt would love it,” she told Gigwise in 2015. “So we went there and he dropped, I think it was over $4,000, and he wrote a check and then, he told me later on, they never cashed the check because it was his autograph!"

Cobain discussed his BareBones shopping spree with Canadian television channel Much in 1993. “I bought all these fetuses, anatomy men, and charts and stuff—it’s like a dream come true,” he says. Some of the anatomical models are immortalized in the collage Cobain created for the back cover album art of In Utero.

Despite celebrity shoutouts and media attention, “that part of the business didn't pan out,” says Cordell. He doesn’t recall exactly when the Mall of America location shuttered, and MOA’s press office wasn’t able to provide a closing date. The final local newspaper mention I could track down was a St. Paul Pioneer Press “Business Beat” column from December 1, 1999. The space is currently home to Sweet Paris Crêperie & Café.

Cordell sold the Anatomical Chart Company around 2000. After waiting out his non-compete agreement, he partnered with his son Adam to launch Anatomy Warehouse. Today, the company’s online store sells anatomy models, anatomy charts, and healthcare simulation materials directly to consumers—an echo of BareBones for the e-commerce era.

Micha recently retired after 41 years with The Kubala Washatko Architects, during which he designed over 500 churches, as well as hotels and nature centers. “We started to shift [away from retail] into projects that had a sense of timelessness,” he says. “It’s a special kind of privilege to do it right and to make certain that what you leave behind is something that is going to be an asset to the community.”

Stockert still regularly visits the Mall of America and covers its newest offbeat attractions on her blog. “There's always something unique there, but it's not that same wild, out there kind of stuff that I remember when it first opened,” she says. “It's more practical shopping than whimsical, weird shopping like it used to be.”

As I worked on this story, everyone I mentioned it to wanted to know why—why bother writing about a store that closed 25 years ago? My superficial answer was that the brief mentions of BareBones piqued my interest.

But there’s a deeper, truer reason. If the memento mori skeletons carved into tombs were a reminder of the inevitably of death, BareBones reminds me of the possibilities of life. We have to work within certain constraints—the square footage of a retail space, the years of a human lifespan—but we can still craft something wacky and wonderful, something that sparks curiosity and inspires others. And maybe, if we’re lucky, the memory of what we created will linger on long after we’re gone.