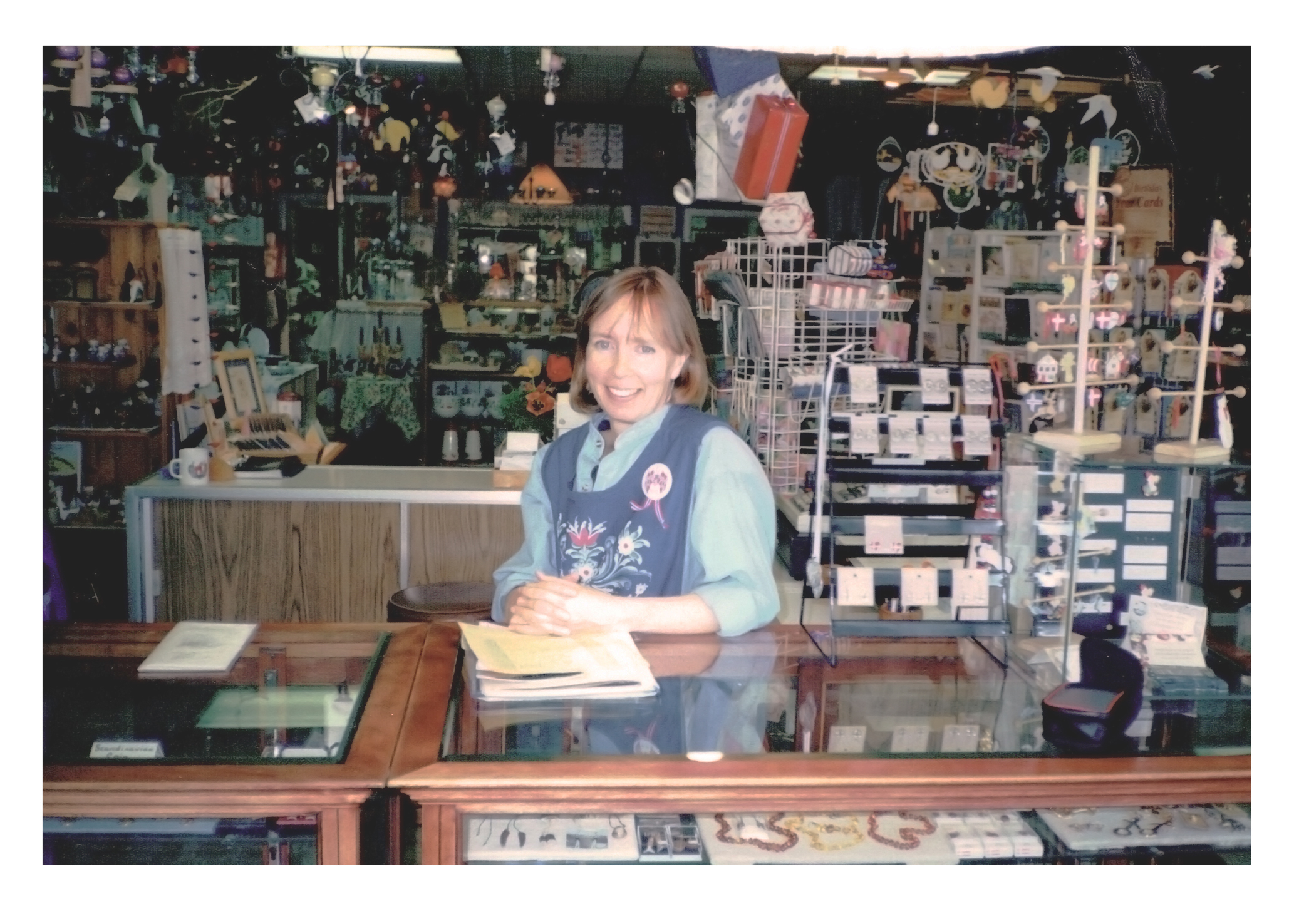

In 1974, Julie Ingebretsen started a job that would keep her occupied for the next 50 years: managing the gift shop at Ingebretsen’s Nordic Marketplace.

“I was sort of between jobs,” recalls Ingebretsen. “I had done education for a while and that wasn't working the way I hoped it would, so I was looking for something else to do. I still remember my silly vision of what it would look like: I’ll put some stuff on some shelves, and I’ll sit at the cash register, and I’ll have time to read.”

Ingebretsen’s Norwegian immigrant grandfather, Charles Ingebretsen Sr., had founded the meat market and deli adjacent to the East Lake Street gift shop in 1921. Her father, Charles “Bud” Ingebretsen Jr., took over the market after WWII and brought a partner, Warren Dahl, into the business. The duo purchased the building in 1974 (at the time, their business occupied one of the building’s four storefronts) and decided to add a Scandinavian bakery and gift shop. Julie Ingebretsen was tasked with managing the gift shop.

“I learned I knew absolutely nothing about business!” she says with a laugh.

She remembers not knowing how much to mark up the merchandise, since her family’s grocery experience wasn’t relevant to gift items. “They had no idea what to tell me to do. So I just sort of guessed. I got a call from one of my competitors not long after saying, ‘What are you selling blah, blah, blah for?’ And I told them, and [they said] 'You can't do it for that!' I was learning by making a lot of mistakes.”

Eventually, Ingebretsen’s husband joined her at the gift shop, and she appreciates that they were able to take turns working and caring for their children. The gift shop gradually expanded from a small counter to its current form as Ingebretsen’s Nordic Marketplace, spanning four former storefronts and including a butcher shop and deli, gift shop, needlework store, and classroom for Nordic craft classes.

Much of the gift shop merchandise is imported from the Nordic countries of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, and Finland, and there’s also a robust kitchen section with pans, tools, and dish towels. The shelves of books—one of the shop’s best-selling categories—range from gritty Nordic noir to illustrated children’s books. There are colorful notebooks, elegant silver earrings, glass candle holders, salted black licorice, and bars of lingonberry-scented soap.

Ingebretsen estimates there were about 20 similar Scandinavian gift shops in the Twin Cities in 1974. Today, Ingebretsen’s is the only one that remains, with a handful of local Nordic shopping options including the American Swedish Institute Museum Store and Scandinavian North in Stillwater. (The gift shop at Norway House is an Ingebretsen’s outpost.)

“Why did we survive and all the other 20 have disappeared? I think there are a lot of reasons,” muses Ingebretsen. “Part of it was the combination of the meat market and the gift shop—I think that’s unique. The food is the heart and soul for sure.”

She also notes that Ingebretsen’s has evolved to embrace contemporary Nordic culture. For example, the shop stocks simple, minimal decor and housewares in addition to offering traditional items like cardigan sweaters and lefse-making supplies.

“The immigrants who came over here didn't change much—they held on to a lot of the old stuff and kept some of the old traditions going,” Ingebretsen explains. “But back in Scandinavia, they kept evolving. We try to strike a happy balance between the two, between the updated, modern, contemporary stuff and the older stuff. How do they relate to each other, and how do we navigate that?”

That balance is especially apparent during the gift shop’s busiest time of year: Christmas. “It’s probably the most traditional holiday, the one with the deepest roots,” says Ingebretsen. “[People think] Grandma always did this, so I want to do that again.” To that end, the shop is stocked with Swedish angel chimes that gently twirl with the heat from candles, advent calendars filled with Danish chocolate and licorice, and tomtar figurines depicting the domestic sprites that protect Scandinavian farmsteads in exchange for Christmas porridge.

However, not all of Ingebretsen’s customers are looking to connect with their heritage. “We have plenty of customers who aren't Scandinavian in any way, but they like the aesthetic. They like the feel of it,” says Ingebretsen. “Things made in Scandinavia, or designed there, there's such an emphasis on doing it the right way, quality-wise, sustainability-wise, all of those things are important. I think a lot of people appreciate that a lot. I appreciate it.”

For some, a visit to Ingebretsen’s has become a Christmas tradition in itself. “It’s a really old business that’s been through a lot, and it's important to a lot of people—they would seriously miss us if we were gone,” says Ingebretsen.

Ingebretsen is hesitant to predict the future since there are so many unknowns. In the recent past, she’s had to navigate the uncertainties of the COVID pandemic and the unrest following the murder of George Floyd. The neighborhood has changed dramatically since her grandfather opened his meat market in what was then a Scandinavian-American business district known as “Snoose Boulevard.” Today, Ingebretsen’s Nordic Marketplace is surrounded by Mexican bakeries and taquerias, halal butchers, and East African restaurants.

“We're really pleased to still be a part of what goes on here on Lake Street with our immigrant neighbors, who are all part of this really interesting place,” says Ingebretsen. “We're just happy we can stay and that enough people appreciate our staying and come down and support us. Even though not many of our customers live nearby, they keep coming back.”