Sean Sherman’s Turtle Island: Food and Traditions of the Indigenous Peoples of North America is a stunning, ambitious cookbook, spanning several regions across North America—or, as it’s referred to in many Indigenous cultures of this land, Turtle Island.

The book itself is historic: a broad introduction to North American Indigenous cuisine, with chapters featuring recipes all the way from the Canadian Arctic to the Mesoamerican Rainforests of Southern Mexico. The Eastern Woodlands of what’s now known as Massachusetts, New York, and Maine are featured, as are the many Indian nations in Oklahoma and the deserts of the Southwestern U.S. and Northern Mexico. And of course, there’s a Great Lakes Section.

With Sherman’s restaurant Owamni located here in Minneapolis, along with his marketplace Indigenous Food Labs, the Twin Cities are a core part of the book, and so are the local people who worked with Sherman to help make it happen, including co-author Kate Nelson; Mecca Bos, who did the recipe-testing; and Linda Black Elk, who foraged ingredients along with her husband, Luke Black Elk.

Meet the Team

Before joining the Turtle Island team, Kate Nelson, an Alaska Native Tlingit tribal member and award-winning writer and editor, had followed Sherman’s work and covered Owamni for publications like Esquire. “We had a lot of shared space, both here in Minneapolis, and other places within the Native community across the country. We developed a nice rapport,” Nelson says.

In 2021, Sean’s partner Mecca Bos hosted a launch party at the couple’s home for her own initiative, BIPOC Foodways Alliance. At the gathering, Sherman told Nelson that the book was going slower than he expected and had hit a few obstacles, and asked her if she could help with the Alaska chapters. “The next thing I knew, he was asking me to come on as a co-author,” she says.

For Nelson, the timing felt ordained. “[It] coincided with me embracing my Indigenous side of my background, so that seemed serendipitous," she says. "We'd already developed that warm, trusting relationship, and I was able to capture his voice in different articles, so he felt comfortable with me helping capture his voice and sharing his mission, his work, and his story in this book. It came together in a way that felt organic, like the universe conspired for it to happen.”

To tell this story, Sherman and Nelson created something almost more akin to a history book than a traditional cookbook. “We've never actually crawled out of American colonization yet,” Sherman says. “My work has always been steeped in just exposing true American history to everybody, and here, we’re utilizing something like a cookbook to slip in a whole bunch of history.”

Telling that history was necessary to set a political intention, particularly an effort to dismantle the ideas of colonial borders that separate Turtle Island into nations and are used to persecute immigrants, people of color, and Indigenous people.

“This kind of cookbook has never existed before, which is why it needs to exist,” Nelson adds. “But that meant that there was no roadmap for us. So we were really carving out our own path as we went. There are already other Native chefs and thought leaders who are coming out with cookbooks and memoirs and all of these really important works of art. And the hope is that Turtle Island breaks open the opportunity for even more people.”

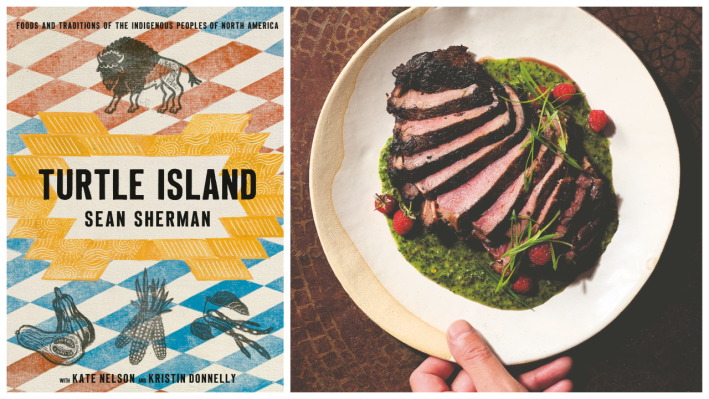

Jaida Grey Eagle, an Oglala Lakota photographer based out of St. Paul, started working on Turtle Island as a way to challenge herself. Grey Eagle’s specialty was documentary photography and portraiture. Even though she’d done some food photography for Bon Appétit and Owamni, she’d never photographed an entire cookbook before.

So Sherman brought her on as an assistant photographer, for a sort of crash course in food photography. “It was a lot of really long days and hard work, but it was also a lot of fun,” says Grey Eagle, who thinks food photography is one of the more collaborative forms of photography. “We had an on-set prop stylist and then a food stylist ... It just takes so many hands to create one photograph.”

Grey Eagle also helped connect the book’s creators with local artists who made the pottery or basketry that helped style the dishes, like ceramicist Chanel Gallagher and weaver April Stone.

Linda Black Elk, an ethnobotanist with Sherman’s non-profit NATIFS, and her husband Luke, Food Sovereignty Director at Makoce Ikikcupi, did much of the foraging for the book, going out to bring ingredients back to Sherman’s home for Bos to test in the recipes. Although Turtle Island can feel like a daunting book, Black Elk stresses that so many of the plants needed are right in front of you.

“Luke and I were struck by the dependability of these plant relatives, that we could rely on them to be there for us,” Linda says. They also foraged with culture and responsibility in front of mind. “Sustainability is super important, and in harvesting, we made sure to follow all of the Indigenous protocols that were put in place by my husband's family and by the people who came before us.”

Even their children got involved in the project, which Black Elk says was a great learning and bonding opportunity. “Now our 10 year old looks at some of the pictures in the book and he's like, ‘I remember harvesting that with you.’ It's such a great way to get your kids involved and to help them to build relationships with traditional foods.”

Sherman’s partner Mecca Bos, who leads both the BIPOC Foodways Alliance and its offshoot program, Immigrant Kitchen, first told me she was recipe-testing Sean’s book in 2022. Three years later, she says it was a culinary adventure she’s missed since the project ended.

“This book kept me in the kitchen daily, in a real and special way,” she says. Bos, who has worked as a food journalist and a professional chef, says it was a beautiful experience to “wake up every day, cook, and have our whole house filled with these beautiful and evocative aromas. Our next door neighbors loved us too because there was no possible way we could eat all the food, so there was always extra.”

For Bos, Sherman and recipe writer Kristen Donnelly’s talent made the huge task easier; about 75% of the recipes she tested would come out great the first time around.

And as the recipe tester, Bos also fed the Twin Cities team. “I got to try most of the dishes that we photographed,” Grey Eagle says. “Oh my god, they were amazing. Some of those dishes I still think about on a daily basis, like the duck egg aioli. I hope everyone makes it. There was also this dish that I've never tried, but it comes from out of Oklahoma, it’s called grape dumplings.”

You Might Not Be Able to Cook Every Recipe—And That’s The Point

With recipes like California Bear Stew, Iguana with Green Mole, and Seal Tartare, Turtle Island isn’t necessarily designed to be a cookbook where making each recipe is accessible no matter where you live.

“That was part of the gist,” Sherman explains. “This book isn’t designed so you find everything at your local Whole Foods, but instead it’s designed so that you might not even get to try some of these recipes unless you happen to be in the right region at the right time with the right people. We don't have to have access to everything, just because we want it. There's some things that are special, and there's some plants that are special.”

For Bos, sourcing was one of the more challenging aspects, but she and Sherman relied upon their community relationships. “Sean has a pretty vast network of people around the country, and we would also have Sean's dad or uncles or cousins hunt sometimes for us,” she recalls. “We got some beaver meat that way, sent on ice via FedEx. We’d just be opening up these crazy packages of unidentified hunks of meat.”

Things didn't always go as planned, though. “I'll never forget opening up that package of beaver, and somebody had unfortunately punctured the stink gland. And I told Sean, ‘Hey, I don't know what beaver is supposed to smell like, but I don't think this is anything I should be putting in my mouth.’”

Cooking Through This Book Is Easier—and Cheaper—Than You Think

Despite the uniqueness of some ingredients, making these recipes isn't always a big challege. “The vast majority of the recipes are accessible to the average home cook, especially if you're willing to put in a little extra work to get the stuff,” says Bos.

Many of the ingredients, including the game meat and plants, are now available at specialty purveyors or boutique grocery stores. But Bos strongly recommends building relationships and buying directly from Indigenous producers. Just because you might be able to find a website to order seal meat from doesn’t mean you should.

“Immerse yourself in the hyper-regionality of it,” Bos says, “because that's the way that people used to cook and eat. And arguably, if we were eating and cooking that way now, we would be in a much better place.”

In the Great Lakes section particularly, so many of the ingredients are in your backyard. I made the wild rice-crusted walleye cakes with wild rice from Indigenous Food Lab and walleye fish from Jake’s Country Meats.

I also needed burdock root, which Black Elk told me was easy to forage, but I could find in pretty much every Asian grocery store. “It is also a very important Indigenous food here on Turtle Island, and it is also considered a very important food for Koreans in particular, who will make a banchan, which is like a side out of the burdock root,” she explains.

Anise hyssop—which is good for lungs and digestion—is easily forageable in woodlands and prairies. And according to Black Elk, now is the time to look for rosehips in unsprayed rose gardens, a season that will be going on until well into the deep winter here in Minneapolis.

Imagining Different Food Futures

Even though everyone I interviewed for this piece lives in the Twin Cities, many of them felt the book helped them connect to their homes. For Grey Eagle, who grew up on Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota (also where Sherman grew up) the Great Plains section resonated with her deeply.

“I think Americans call it tripe, but we call it taniga. It's the guts of a buffalo or a cow, and Sean included that recipe because we all grew up eating that as Lakota people,” she says.

Grey Eagle feels like right now, as the people all over Turtle Island and especially within U.S. borders grapple with worsening food insecurity, people will look to this book for guidance. “I think Indigenous foodways have a lot of answers to a lot of our problems, like climate change and environmental stewardship,” she says.

“Growing up, we didn’t have access to a lot of foods if it wasn’t available in a supermarket or some kind of system. It was through the land and through your own family and just spending time on the land. I think about picking timpsila as a family or going out with my sisters and getting wild peppermint for the team,” she explains. “When I think about our food, I don’t think in terms of supermarkets or money. Our food exists outside of capitalism. But it’s going to take a really long time for us to get back there because we've been very intentionally removed from land.”

“Indigenous communities have community-based food systems,” says Sherman. “Everybody worked hard and played a role in their food system, whether they're farming, gardening, gathering, hunting, fishing, tending soil, tending plants—whatever it might be … I want to showcase what America has been and can be, rather than someplace that has completely ignored or destroyed Indigenous food systems.”

As an Alaska Native, Nelson felt it was crucial to depict the foodways of the people of the tundra and the Arctic authentically, even if that meant people couldn’t cook things like seal or beluga whale. “In the lower 48, we feel pretty detached from Alaska, and the far north and the Arctic,” she says. “We wanted to help readers understand that in these Alaskan and far north communities, a lot of these food traditions have been carried forward out of survival. Food sovereignty is synonymous with food security for many of these communities, which is a reality that is really hard for the rest of us to imagine.”

In remote northern communities, where all the food must be flown in and small amounts of chicken or beef can cost anywhere from $50-100, hunting, foraging, and preserving food that the land provides—not a company—is the only way.

“In some of these communities, [subsistence hunting, fishing, and foraging] makes up the majority of their food source,” Nelson continues. “It's not something they do as a hobby or as a pastime, it's a year-round process because otherwise their families and their communities wouldn't eat, especially in the winter.”

For Nelson, her approach to telling Indigenous stories is one that resists extractive philosophies of white supremacy, and instead relies on political intention and equitable collaboration. “It's important that we think about and are really intentional about how we're engaging with Native communities, both as Natives and non-Natives,” she says. “It isn’t just about ‘What can we get?’ or even ‘What can we learn?’ but ‘What can we all share together?’”

“My hopes are that we can start to see and appreciate the immense diversity that we have as Indigenous peoples, but realize that we're all deeply connected, and that there is strength in numbers,” Sherman says. “I would hope that Black and Indigenous people could come together more, to really stand stronger and to see that we share so much of the same violent history, but we can also see a path through to how we can heal.”