For a 20-year span around the turn of the millennium, Minnesota sprouted new music festivals the way it produces sugar beets and turkeys.

Between 1995 and 2015, in chronological order, nine major fests emerged within proximity to the Twin Cities: Basilica Block Party, Rock the Garden, 10,000 Lakes, Soundset, SoundTown, Summer Set, River’s Edge, Festival Palomino, and Eaux Claires—whew!

Today, they’re all dead. Long-running, multi-day country blowouts like WE Fest and Winstock persist, but for local fans of rock, hip-hop, and pop, few festival options exist.

"It's really fucking hard to do a festival, and increasingly expensive,” says First Avenue GM Nate Kranz, who helped coordinate Festival Palomino for three seasons. “It comes down to economics."

That is, more or less, the picture that emerged as we interviewed promoters, organizers, musicians, music critics, and radio bosses to answer the question: What killed the Twin Cities music festivals?

A Brief History of Recent Doomed Fests

Randy Levy has been booking bands since 1969. Back then, the University of Minnesota student could land John Denver or the Grass Roots for $1,500. By the ’70s, Levy’s company, Schon Productions, was in business with much higher-dollar acts like J. Geils Band, REO Speedwagon, Johnny Winter, and Bruce Springsteen. Later, as an exec with Live Nation, he’d assist with mega-tours from the Rolling Stones to U2.

Levy entered the festival arena in ’85 when he became part-owner of WE Fest, which he and his partners sold to Connecticut-based Townsquare Media in 2014. “They ran it into the ground; it's only around because Live Nation went in with the existing landlord and saved it,” Levy told us by phone after a round of golf at Palm Springs. Levy’s newer company, Rose Productions, would assist throughout the 12-year run of Rhymesayers Entertainment’s Twin Cities-based rap fest, Soundset, in addition to seven years of working with the jammy 10,000 Lakes Fest in Detroit Lakes and three with the rootsy Festival Palomino in Shakopee.

“Things change. I think, over time, some ideas go flat. To me, it's not a death knell,” Levy says of the semi-recent demise of so many area festivals. The viability of a music fest, he argues, is tied to three core questions: Is there a fanbase? Are there sponsors? Is there affordable talent?

That latter Q slid the nail into the coffin of Soundset, which became one of the country’s largest hip-hop gatherings until it shuttered after 2018. Early lineups served more as label showcases for RSE, though the top billings eventually featured the genre’s all-time heavyweights: Lil Wayne, Snoop Dogg, De La Soul, Ice Cube, J. Cole, Future, Lauryn Hill, Erykah Badu, and SZA, just to name a few.

“We got hooked with talent that cost too much one year,” Levy says, noting that fan demand was never an issue. “We lost too much money in one year. We all survived, but neither of us should be handling that big of a loss."

One of Levy’s Palomino partners, Kranz of First Ave, says his team remains proud of that festival’s lineups, which were curated in conjunction with Duluth-launched bluegrass stars Trampled by Turtles. Over the years, they included the Head & the Heart, the Arcs, Andrew Bird, Dr. Dog, Father John Misty, Low and, of course, TbT. The fanbase just never solidified.

“Honestly, it was a whole lot of work for everybody involved, including Trampled by Turtles,” he says. “It just did not compute with what the attendance figures were. It was a lot of risk, a lot of work, and we just didn’t see room for growth.”

Another artist-driven festival, Eaux Claires, was dreamt up in 2015 by Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon as a deliberate counterpunch to the corporate festival experience. Vernon told the The Guardian the festival was intended as a rebuke of “all the things I hate at festivals: really loud music all the time, no breaks, bad food, all that kind of thing. Why would you make your rock ’n’ roll festival the Sony PlayStation Stage? Why would you take the money to do that? You’re working against rock ’n’ roll, you idiots!”

It delivered on that promise for four summers, bringing the National, Paul Simon, Chance the Rapper, Lizzo, the Indigo Girls, Wilco, and Sufjan Stevens to Vernon’s home turf in the woodsy Chippewa River Valley. But Eaux Claires organizers took off 2019 to recalibrate the festival, saw it mothballed due to COVID-19 a year later, and, now, it’s not clear if it will return.

An hour west of Eau Claire, at the Live Nation-operated Somerset Amphitheater near the Wisconsin-Minnesota border, some fests endured while others sputtered out almost instantly. The three-day Summer Set fest ran there from 2012 through 2017, always offering a drug-friendly mix of EDM, jam bands, and a little rap. Skrillex, Chance the Rapper, Bassnector, Umphrey's McGree, the Weeknd, Grimes, Big Gigantic, and Nas are among the names who performed along the Apple River. SoundTown, with its 2011 lineup of the Flaming Lips, the New Pornographers, and Devotchka, only made it through one run, even though Jane's Addiction, Weezer, and Florence and the Machine were announced for the canceled sophomore edition; organizers cited low ticket sales. (Willie Nelson’s Outlaw Fest is the lone, bright festival slotted on Somerset’s summer calendar this year.)

Speaking of one-’n’-done festivals, Live Nation invested $4.8 million into River’s Edge and, in 2012, told St. Paul leaders the two-day fest would rock Harriet Island for at least five years. After Dave Matthews Band and Tool managed to draw 45,000 fans for the inaugural fest, the corporate concert giant shut down River’s Edge.

“It was an enormous loss. But big deal! They're a big company, and they made that weekend doing 10 other things,” Levy says. “So it's just, you know, it's a fragile tent. If too many of these things go against you…”

The two biggest multi-day Minneapolis festivals—Basilica Block Party, launched in ’95, and Rock the Garden, launched three years later—were sunset for less obvious reasons.

"The purpose of doing those events is for branding, as they would call it,” speculates Jon Bream, the Star Tribune’s music critic since 1975. “And I don't know if it makes sense to spend that much money for a promotional event that doesn't necessarily make money. What's the return? Is it really making a difference?"

For decades, BBP catered to Cities 97 sensibilities—think Jason Mraz, Cake, Brandi Carlile, the Fray, Weezer, and Train—while serving as a boozy collection plate aimed at restoring the Basilica of St. Mary. The churchy party was sidelined by COVID-19 in 2020, but returned in 2021 only to be canceled yet again for 2022 and 2023. "The event is on a planned hiatus this year and will be reconsidered in the future," church officials said via press release this past March. (Like so many prayers to god, Racket’s interview request to the Basilica of St. Mary went unanswered.)

Rock the Garden, meanwhile, signaled the start of summer for 89.3 the Current-listening fans of Bon Iver, the National, Sleater-Kinney, Modest Mouse, and the Hold Steady who’d watch from the grassy Walker Art Center hillside.

“It was a mutual choice between two nonprofit organizations [the Current and the Walker] who were, once a year, trying to step into the shoes of an event promoter,” says David Safar, managing director/host at the Current. “It’s a lot. At some point you gotta decide when you’re going to go.”

As for whether it might stage a comeback? Don’t expect a RTG reboot anytime soon.

“I don’t think I can answer that question without the Walker crew,” Safar says. “We haven’t even talked about it.”

What’s Killing the Fests?

“You're not alone in being a little bit puzzled by it,” says First Ave’s Kranz. “Especially when I look to places like Chicago where you could say, jeez, one could argue they have too many festivals. But people keep going…”

He’s not kidding: Prominent Chicago festivals include Lollapalooza, Pitchfork Music Fest, Riot Fest, Chicago Blues Fest, North Coast Music Fest, and Windy City Smokeout, while Milwaukee (Summerfest, touted as the world’s largest music fest) and Des Moines (80/35 Music Festival, a constant for 15 years) both manage sustained urban festivals. Logistically, Kranz notes, the Twin Cities metro is at a disadvantage due the absence of obvious locations that can accommodate large-scale, multi-day outdoor festivals.

If there’s an across-the-board culprit for the disappearance of Twin Cities-area festivals, rising costs were the top-cited reason referenced to us: talent, security, rentals, gas, hotels, food, you name it, all made worse by inflation and pent-up demand from the pandemic.

As artists make less and less in the age of streaming, live performances have become the dominant income stream. That’s being reflected in the sums they can demand from festivals. At Woodstock ’69, Jimi Hendrix took home the modern-day equivalent of $125,000, according to this explainer from The Economist. Ariana Grande, at Coachella 2019, earned a $8 million payday. And that, of course, plays into the current reckoning over skyrocketing concert ticket prices and fees. Earlier this year, Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota grilled Ticketmaster executives during a U.S. Senate judiciary hearing, taking particular aim at the de facto monopoly the company enjoys—70% of tickets sold for major U.S. concert venues are funneled through Ticketmaster. (AEG Live is the other corporate behemoth in the concert game.)

After listening to her husband and this reporter yammer about festival economics for 30 minutes via speakerphone, Randy Levy’s wife, Katrina Levy, politely interjected with the elephant in the room: Live Nation, which owns Ticketmaster and operates dozens of venues including, locally, the Uptown Theater, the Varsity Theater, the Fillmore, and the Somerset Amphitheater.

“A lot of the cool, interesting festivals were independently promoted, and those are the ones that broke under the pressure of the new, consolidated market. They were no longer viable,” she says. “I think what Minneapolis has to look forward to is festivals that cost as much as Coachella in the future, because that’s what the market is turning into—this giant business. The cost of shows will triple over the next five to 10 years. Who cares what it does to consumers? It’s the trouble with a world where everything is about shareholder value.”

The looming, growing, and much-derided impact of Live Nation came up again and again throughout our interviews. “They have a ginormous advantage when it comes to sponsorships, and that’s especially true at the festival level,” says Kranz, adding that the brand-dominated aesthetics and “experiences” of modern festivals have only gotten more saturated since being spoofed by The Simpsons almost 30 years ago.

Adds Bream:

“Live Nation can kind of leverage themselves into controlling all these acts. And so you overpay for Dave Matthews and Tool. Now you've got them [contractually] next time they come to town. It’s risk/reward. And, you know, when you're Live Nation, you can roll the dice a lot more than if you're an independent promoter. The landscape has just changed. It went from an indie world to a very consolidated world controlled by a monolith.”

Who’s Making it Work?

Now entering its ninth year, the Blue Ox Festival is perhaps the lone survivor of the ’10s Twin Cities festival boom. Curated by Minneapolis bluegrass faves Pert Near Sandstone, the event is something of a throwback to the Newport Folk Fests of yore—string-based acts, musician workshops, and, crucially, vibes.

“When you're talking about the front of house, and everything on the camping side, they nail it every year,” says Justin Bruhn, the bassist for Pert Near. “We have the best porta-potty people, and that goes a long way with festival goers. People love our festival, the vibes and the minutia.”

Co-owner Mark Bischel is a second-generation festival organizer. His father, Jim, founded Country Jam in 1989, and it has been held every year since at the Bischel’s Pines Music Park outside of Eau Claire, Wisconsin. Blue Ox was originally conceived as a Country Jam offshoot, though the Bischels opted to make it a standalone fest, one that has hosted bluegrass, Americana, and folk acts such as Jason Isbell, Béla Fleck, Trampled by Turtles, Margo Price, and Gov't Mule. Beyond live music, Blue Ox offers attendees a yoga/meditation tent, instrument and songwriting workshops, "Potluck Pickin'" spaces for audience jam sessions, nine-hole disc golf, kiddo entertainment (“an investment in the future,” Bruhn explains), and art installations.

If country and EDM festivals are lifestyle events for booze and drugs, respectively, this family-friendly enterprise functions as the laidback alternative for those seeking communal sanctuary in the woods. (Elsewhere, smaller, rural, niche festivals—like the DJ-based InfraSound and jammy Shangri-La Festival, both located in Clarks Grove, Minnesota—have persisted.)

What’s the secret formula for Blue Ox?

“Short answer is I guess we probably get lucky,” Bischel says with a chuckle. A slow-build strategy may have contributed to that luck. Bischel reports Blue Ox has grown by about 400 guests per year, and this season’s installment is capped at 5,000 multi-day passes. It’s projected to be the first-ever Blue Ox to sell out.

“It’s really tough to compete against those higher-level companies, but I think there’s some value to being smaller,” Bischel says. “Part of staying under budget is searching for newer, up-’n’-coming bands instead of chasing the currently popular people. We’ve lucked out. We got Tyler Childers and Billy Strings when they were very much affordable. Now, we couldn’t afford either of those acts. It’s being opportunistic and knowing what your budget is.”

Having the Pert Near guys around to help scout talent is a big advantage, Bischel says. The band also doubles as annual co-headliners, removing yet another costly question mark. This year, they’ll be joined by the Avett Brothers, Sam Bush Band, Mike Gordon, and Charley Crockett.

“There are so many things that can kill a festival: budget, personalities, mismanagement. Maybe you blow your load on a band, and the return isn’t there. It is kind of a bummer,” says Bruhn of Pert Near. “It's sort of interesting how they've all kind of faded. I mean, it's a drag… it's like, why can't we maintain this?”

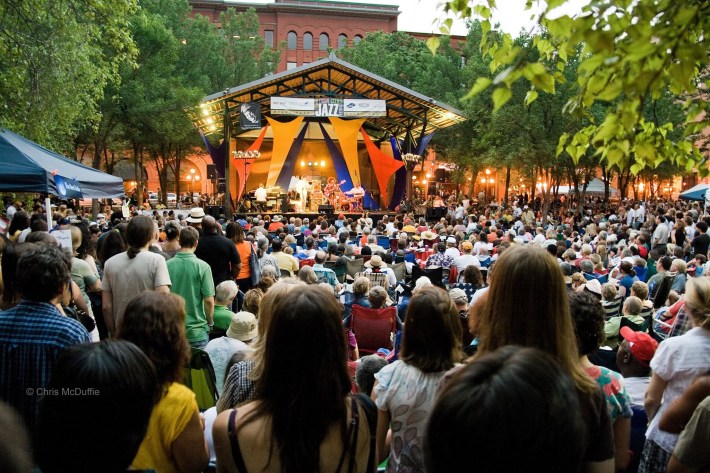

The Twin Cities Jazz Festival has been maintaining its annual St. Paul takeover since 1999.

“It was meant to do something different,” says co-founder Steve Heckler. “I expected 300 people would show up to sell CDs and promote jazz, and thousands showed up—at least 3,000!”

Nowadays, the fest draws upwards of 40,000 people over three days to its hub stages inside Mears Park and satellite venues across the city, Heckler reports. Run as a nonprofit, the free Twin Cities Jazz Fest has lured talents like Curtis Fuller, McCoy Tyner, Chick Corea, and Grace Kelly over the years. (Heckler, a true jazz-head, becomes audibly overwhelmed when asked to choose favorites.) Artists are contractually obligated to participate in clinics with young musicians, adding to the community-first vibe that attracts hundreds of volunteers each year.

Heckler admits it’s not all sunshine for the T.C. Jazz Fest. He reports the price of reserving parking meters has ballooned from $300 to $6,000, security costs have tripled, and new expenses, like the thousands now required to install concrete road barriers (“They bring a crane out to drop the damn thing!”), keep popping up. But between grants, donations, sponsorships, and sales from food and beverages, the event stays in the black.

“We’re community organizers that like jazz. It’s an attempt to create vibrancy in the city—we’re not competing against Basilica Block Party and those types of events,” Heckler says. “We’re niche, we’re flexible, we’re not dependent on ticket sale revenue. Flexibility: That's how we survive; that's what saves us.”

What’s the Future for Fests?

“When there’s a hole like that in the market, I would guess somebody would try to fill it,” Kranz says, adding that First Avenue has no immediate plans to stage a festival. Safar from the Current is also bullish on the future of Twin Cities fests, predicting: “You’re going to see another wave in the coming years, of folks taking their swing at a large-scale, bespoke outdoor event.”

We’re already seeing some semblance of that with Target Field’s recently announced TC Summerfest concert series with the Killers and Imagine Dragons. In practice, however, that event is more back-to-back beefy ballpark bills than an actual festival; the two-night ticket passes—$126 for nosebleed, $372 for on the field—are priced as soaringly as a dinger coming off Joey Gallo’s bat.

And, of course, there’s the return of Taste of Minnesota, the two-day free festival along Nicollet Mall that city leaders are framing as a Minneapolis-is-back victory lap. Nobody we spoke to for this story expressed great optimism for the event, which is effectively a Third Eye Blind concert followed by a Big Boi one with lots of food trucks and some wrestling.

“I mean, I liked the idea of Taste of Minnesota. I don't understand the logistics, how it's gonna play out on the Mall… I just can’t envision how it’s going to work,” the Strib’s Bream says of the food ‘n’ tunes bash that dates back to 1983. Taste was held outside the State Capitol through the ‘80s and ‘90s, relocated to St. Paul’s Harriet Island in 2003, and, finally, lasted for a couple of years in Waconia before shutting down in 2015; its colorful cofounder and face, the late Ron Maddox, was known to patrol the grounds by golf cart with a baseball bat that read, “You agree with me, don't you?"

Summoning his trademark peppiness, Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey hyped the rebooted event earlier this month to reporters: “This is not getting back to the old normal, we’re attracting new events, new talent, new kinds of experiences—and that's what this Taste of Minnesota is all about.” Curiously, the whole shebang will be made possible by a one-time $1.85 million stipend issued by the state to co-sponsor the Minneapolis Downtown Council, a nonprofit civic booster org. The money is being designated exclusively for Taste of Minnesota, which is expected to draw 100,000 people over two days. Organizers hope to secure a “multi-year commitment” to bring the fest back to downtown following its July 2-3 debut this summer.

In the meantime, the Twin Cities Jazz Fest ain’t going anywhere.

“We feel great about the overall health. We choose, as an organization, to keep our event a certain size,” says Heckler, who’s retiring after this year’s 25th anniversary celebration. “We scaled it to where we all enjoy it. We’re not in competition with Live Nation by design. We’re community organizers who do jazz concerts—we’re just coming at the world differently.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misidentified Live Nation as the owner of the Somerset Amphitheater. Matt Mithun owns that venue, though Live Nation books and operates it; Mithun is also the majority owner of WE Fest, which is co-owned by Live Nation.