This won’t be another online litigation of Joe Rogan vs. Neil Young, we promise.

Rogan—Spotify’s misinformation-platforming, mega-earning podcast star—looks bad. After linking up with Spotify’s much eviler competition, Young—the classic rock icon who yanked his catalog from the music-streaming giant in protest—doesn’t look great. The weeks-long saga has monopolized Twitter discourse, doing little more than further entrenching stances on either side.

But the drama did present us with an excuse to dive deep into the business of music with Minnesota musicians, educators, and label owners. None of them cared to offer up fiery Joe Rogan takes, especially Motion City Soundtrack frontman Justin Pierre, who is only vaguely aware of the controversial podcaster.

“I don’t know that I like him, just, based on his face?” Pierre muses.

We’ll leave it at that.

Of much more interest: Locally, what do music-streaming royalties mean for artists at various strata of the industry, and, more broadly, how do you make a living today as a musician?

“Every artist is trying to figure that out,” says Minneapolis rapper Dwynell Roland. “If you woulda told me people could buy a picture they can’t physically own, and make all this money? I would tell you you’re fuckin’ tripping. Everything is changing and evolving a little bit daily.”

A Recent History of Moving Units

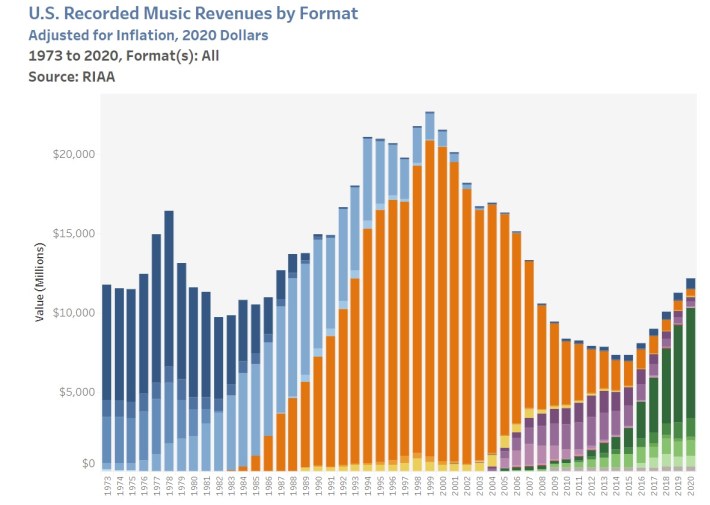

The music industry peaked right around the double-platinum release of Will Smith’s Willenium. In 1999, revenue from record sales topped $20 billion for the first time ever, according to inflation-adjusted figures from the Recording Industry Association of America; CD sales accounted for 88% of that haul. Things would get precipitously worse almost every year into the new Willenium.

“I joke with students today that when I started teaching in 2000, we would explain in the classroom, ‘Hey, here’s how to get Best Buys to consign your CDs,” says Scott LeGere, an assistant professor who teaches the business of music at Minnesota State University. “And look where we’re at now.”

LeGere played in Twin Cities bar bands throughout the ’90s, but had pivoted mostly to studio work by the end of the decade. Launched in 1999, Minneapolis’s Echo Bay Studios was one of the first Pro Tools-focused recording spaces in the upper Midwest. “We were filled to the brim for maybe 18 months, I thought I had the best job in the world,” LeGere remembers. That same year, the Digidesign Digi 001 dropped. For around $2,000, musicians could seize the power of Pro Tools digital recording at home. Business plummeted at Echo Bay.

LeGere stuck it out in the business, landing a job running the studio at Paisley Park around 2004. He received a world-class education in innovative music salesmanship from Prince, who harbored a famously humongous grudge with the major record labels. At the 1995 BRIT Awards, Prince’s acceptance speech was succinct and stinging: “Prince. In concert: perfectly free. On record: slave.”

“I really watched what Prince was doing,” LeGere says. “He was still fighting with the major-label system, but online he had launched the New Power Generation. He was releasing record after record after record, and they’d do well! At a lower price-point, direct-to-fan, and that was really inspiring.”

As LeGere segued into teaching at places like IPR, University of St. Thomas, and McNally Smith, he forged a partnership with St. Paul singer-songwriter Martin Devaney to help local artists sell their records. Together, they watched Twin Cities music makers enjoy the tail end of the CD boom.

“I’d say 2007, 2008, we were getting excited, like, ‘Hey, we sold 50 CDs in Sweden!’ I can write somebody a royalty check for $400,” LeGere says. “That’s a nice little thing to put in the mail for an artist. Almost overnight, as Spotify launched, we went from 500 CDs a month to 50,000 streams in Sweden—you’d go from $800 to $3.40.”

Eric Foss, the owner of Minneapolis label Secret Stash Records, was briefly excited by the subsequent download era. From 2008 to 2015, single and album downloads accounted for over 30% of music revenue, according to the RIAA.

“When iTunes came out [in 2001], it was a windfall,” Foss says. “It was amazing—$1 per track, Apple keeps 30%, and you’re seeing artists and labels split up maybe 50 cents per track. You can do the math and see that add up pretty quickly.”

In conjunction with merch, touring, and the resurgence of vinyl, “it was an ecosystem that made sense,” he adds. The download cost savings were obvious for indie labels: no manufacturing, no storage, no shipping. But, of course, the download heyday wouldn't last.

By 2015, streaming options made up almost 50% of all music revenue, a number that would climb to 83% by 2020. For music executives and streaming platforms, the increasing dominance of streaming helped spike overall revenues to their highest level since 2007—$12.2 billion in '20. For the artists making the music? Infinitesimal per-play royalty rates, as well as every artist swindler’s go-to pittance: exposure.

(You can calculate the grim, platform-by-platform royalty arithmetic here.)

“That’s all messaging that’s coming from billionaire, hedge fund-backed Silicon Valley dickheads and legacy major labels who have a decades-long history of devaluing the shit out of their product,” Foss says. “It’s fucking wrong.”

Streaming Royalties: ‘A River of Pennies’

While on the phone with Racket, Justin Pierre excitedly clicks through royalty spreadsheets that show how much money he earns from his band—’00s emo/pop-punk stars Motion City Soundtrack—in a given year. As he rattles off ballpark figures, some of the results surprise him in real-time.

“Peloton, this blew my mind: $1 per 165 spins—that’s one of the best,” he said of the exercise brand that features “The Future Freaks Me Out” during workout classes.

“$1 per 40 spins on Ultimate Guitar, that was the best one,” he notes.

What the hell is Ultimate Guitar?

“I don’t know!” he says with a laugh. “This stuff just hurts my brain.” (Editor’s note: Ultimate Guitar describes itself as “Your #1 source for chords, guitar tabs, and bass tabs.”)

Powered by Pierre’s cleverly confessional lyrics and blasts of Moog synth, MCS forged a career that took them from Minneapolis basement shows all the way to Columbia Records. Pierre admits he didn’t pay attention to the band’s finances until they got dropped from Columbia following 2010’s My Dinosaur Life. “It’s crazy; we sold more records our first week on Columbia than… I don’t know, it was ridiculous, but it was embarrassing for them,” he says, adding that they’re “so lucky” to be back with longtime indie home Epitaph Records.

The overwhelming bulk of the band’s non-performance profits, Pierre reports, come via the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), the nonprofit that collects royalties from public plays of its members' songs. Mechanical royalties represent a significant piece of the pie, too. The rest, including streaming, “is pretty minimal,” he says. Touring is the group’s financial lifeblood, though that hasn’t happened since the pandemic broke. MCS does have back-to-back nights scheduled for this July at First Avenue, part of a summer tour that kicks off at a throwback emo and punk festival in the U.K.

Still, you might expect a band that racks up 881,746 monthly plays on Spotify alone to be comfortably supported by streaming royalties. Afterall, emo-boom peers like Say Anything (514,691), Hellogoodbye (584,931), and Saves the Day (206,757) don’t come close to that figure. You’d be wrong, but Pierre takes a glass-half-full approach.

“If I added up all the money I make in a year just on royalties through streaming services, I’m able to pay a couple months of my mortgage, which is pretty great,” he says, adding that his wife’s job at Target corporate has carried their family through COVID-19 financially. “But I have 20 years of music out there, and between 150-175 songs I’ve recorded or worked on. We’re like a mid-level nostalgic act now, for all intents and purposes… shit man, I feel grateful for being able to do this as long as I have.”

Diane Miller, who records and performs mononymously as Diane, relocated to the Twin Cities from Fargo in 2018 to make music and, eventually, host 89.3 the Current’s The Local Show. Having not yet produced “a hot-selling record,” she says her streaming royalties are almost insignificant; live shows, merch sales, and Venmo tips from fans make a much larger impact on her bottom line.

“Music fans are so used to streaming music for free that they don't realize the time, energy, and money that goes into the product they are consuming,” Miller says, rattling off expenses like gear, studio time, instrumentalists, and music videos. “This is why you see so many artists feeling taken advantage of by billionaire tech elites who exploit their work without much return.”

Digital distribution companies like CD Baby remain essential for smaller artists, according to Secret Stash’s Foss, even though the label’s catalog of mostly older R&B/soul does much better business being sold direct to customers and record shops. For a flat fee, those companies will upload an artist’s entire discography to the increasingly dizzying list of streamers—Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon, Tidal, Deezer, Pandora, etc. For yet another fee, royalty-collection companies like SoundExchange will automatically collect and distribute payments to an artist's bank accounts.

“It’s like a river of pennies,” Foss says. “You have to get your bucket and scoop ‘em out.”

Even if the bucketfuls feel like slaps in the face.

“Luckily for me, I get a pretty good amount of plays,” says Roland. “Does it feel like I’m getting what I deserve when I get this check? Fuck no, but at the end of the day, I’m still getting a check.”

The Death of Selling Out

In the 1990s and 2000s, a cultural obsession with selling out gripped musicians and, mostly, music fans. That retrospectively privileged debate over authenticity vs. commericialsm is apparently dead. Hold Steady keyboardist Franz Nicolay, whose band never made the major-label leap, even wrote an obituary on the concept of selling out for Slate in 2017. “It never crosses their mind,” LeGere says of his current class of music-biz students.

“You could hate the major record companies,” the professor adds. “But in 1980, if one of them gave you a major deal, maybe, just maybe, the only thing you have to think about the rest of your life is making great art.”

These days, outside of the Billie Eilishes and Harry Styleses of the world, musicians have no such luxuries. On top of writing, recording, and performing your music, you must also become a master marketer of your brand, LeGere says, citing Dessa as a prime example of doing so successfully. Among the Doomtree artist’s various hats: singer, rapper, poet, author, and podcaster with the BBC. She’s a savvy salesperson too, having recently paired the staggered release of her IDES singles with limited-edition merch at every drop. (Through her rep, Dessa politely declined to chat for this article, calling the differences between digital streaming platforms “negligible.”)

In the era of streaming, selling out isn’t a matter of principle—it’s a means of survival.

“It’s a question of diversity,” LeGere says. “We’re still in an era where you can get six figures for landing a song on Netflix; you can get 10 grand for getting a song in an online Target commercial. You look at the licensing money that’s coming out of Fortnite, Peloton—that’s starting to drive meaningful income.”

Foss says he’d advise young musicians to be wise with copyrights, and to explore every possible way to monetize them, including film, TV, and web licensing. While every tree demands shaking, he cautions to not ignore the oldest, most lucrative trunk of all: touring.

“There’s money to be made on the road, if you reach just, even the second tier up from the bottom—festivals will pay you thousands of dollars to show up and play,” Foss says. “You need to look at all of it.”

Streaming Into the Future

LeGere and Foss are, in the short term, bullish on streaming.Their reasoning? Fundamentals of scale.

“Fifteen years in, we’re still in a surprisingly immature streaming market,” LeGere observes. “We still only have, globally, 519 million people paying for streaming music. Versus, ya know, there’s 4.6 billion people on Facebook. If we get more people into the streaming ecosystem paying for it, there’ll be more money. I’m bullish on streaming because I think we have to be. We’re in a streaming mentality for most of our content—the genie is out of the bottle. How do we make the best out of where the industry is clearly going?”

But, as Foss notes, placing your bets on the existing companies means you’re tethered to the “very ugly brand of capitalism” that got us here in the first place, whether that’s retro corporate thieves like Warner Music Group or the glitzier newcomers from Silicon Valley.

“In 2022, if you’re a creative, you can probably do anything on the internet,” Roland says, name-checking the metaverse and NFTs. “You got TikTok literally making people famous overnight. It’s a weird thing.”

We’ve witnessed that weirdness locally with Hot Freaks and Durry, both of whom blew up on TikTok. Hot Freaks had been broken up for six years before scoring a “substantial” one-song record deal with Atlantic Records for “Puppy Princess,” the dance-pop track that exploded seemingly out of nowhere.

“Record labels and artist teams recognize TikTok as one of the most powerful promotional tools in the business,” Ole Obermann, TikTok’s global head of music, tells NME. The Gen-Z-driven social network is changing the music industry, as Business Insider details, even if the actual musicians it popularizes are sometimes left scratching their heads.

“It’s a strange platform, but when it hits it really hits,” Durry frontman Austin Durry says. “I think it’s the future of indie music, honestly.”

Smaller sites like Bandcamp and SoundCloud have made genuine artist-friendly ovatures, like Bandcamp’s weekly waiving of fees and SoundCloud’s new “fan-powered” royalties. But, for now, casual listeners are mostly stuck with market-dominating Spotify or a slightly better-paying alternative like Tidal.

In 2000, the notion of a streamable library stocked with most of history’s recorded music for $10 per month seemed inconceivable, yet we got the first iteration of Spotify six years later. So, what could come next?

Legendary punk-rock crank Steve Albini toyed with possible, less exploitative hypotheticals to streaming platforms on this episode of Pod Damn America, though the fascinating conversation deals mostly in the crystal-ball realm. With the exception of Pierre, everyone we spoke to for this story mentioned NFTs, with varying degrees of skepticism. For some, they’re tech-bro MLMs; for others, including LeGere and Foss, they could potentially re-introduce scarcity into the marketplace for musicians.

“The potential of music is really exciting, and there are more areas of opportunity than we’ve ever seen, but it’s way more complicated,” LeGere says. “We need a lot more community support, we need more helpers, organizations, and individuals being transparent so we can learn from each other and grow.”

In the meantime, Diane Miller suggests some old-fashioned monetization channels.

“If I truly want to support an artist, I buy their music, merch, and see them live in concert.”