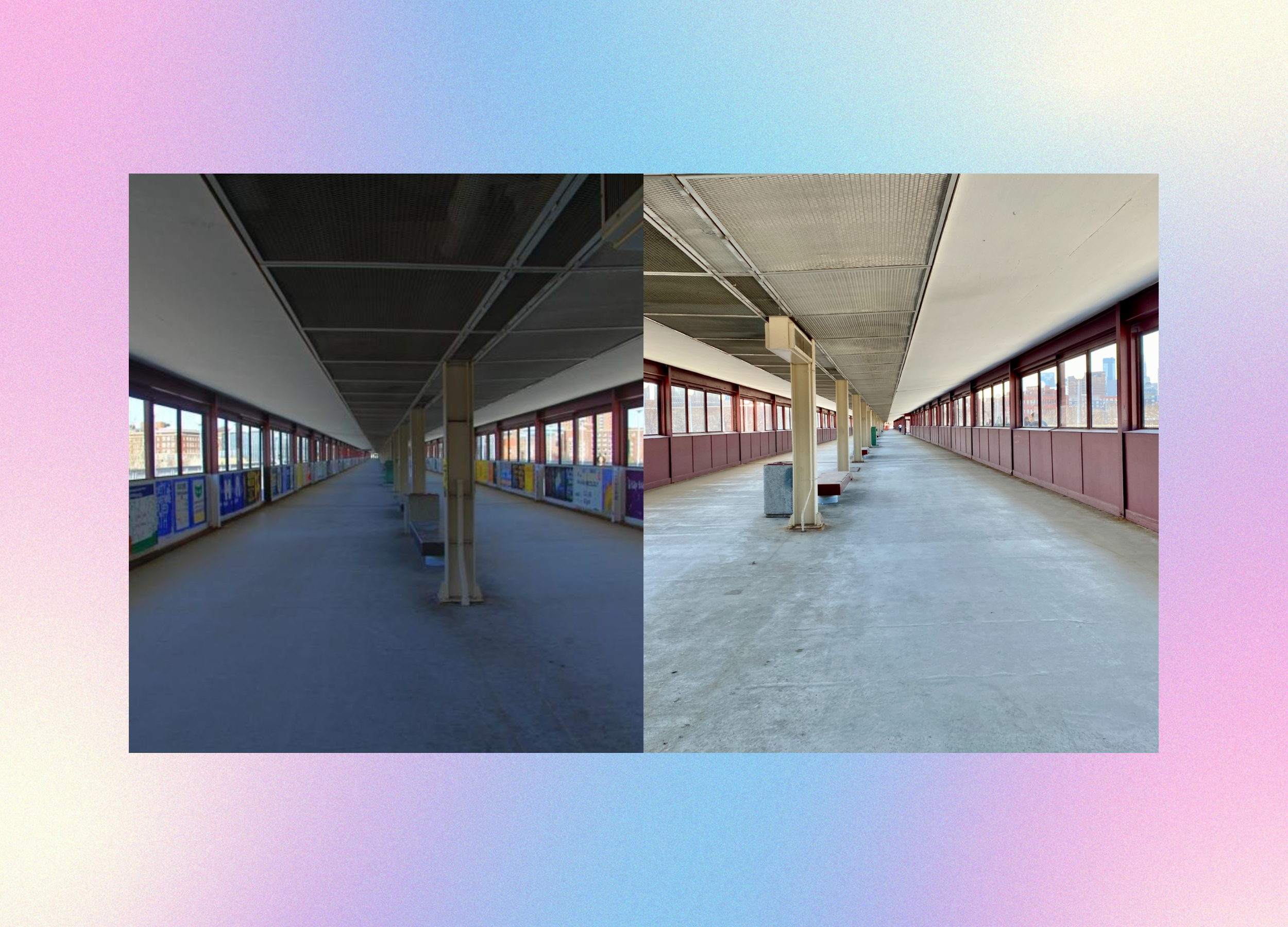

When Bryce Riesner toured the University of Minnesota in the summer of 2020, the bright colors of student club signs along the Washington Avenue Bridge gave him a sense of hope.

Riesner was transferring from Augsburg University, where campus life is almost nonexistent, he says. Seeing painted signs from over 1,000 student organizations spanning the bridge suggested a more vibrant college culture at the U. Clubs included politics, dance, volunteering, and even a Lettuce Club, where students gather for (occasionally viral) lettuce-eating competitions.

As an urban studies major, Riesner was especially interested in how communities are formed, and his plan was to join as many clubs as possible. During his first semester in 2021, however, the university washed the entire bridge with coats of flat maroon paint.

The campus seemed like a different place from the one Riesner had toured. Today, as he walks across the Mississippi River to class on the campus’s West Bank, he still misses the eye-grabbing spectacle the annual “Paint the Bridge” event created.

“There’s nothing to get distracted by,” Riesner says. “It’s just: red panel, red panel, red panel, red panel… eerie liminal space. It was like the reason why I came here was just ripped away from me.”

What Killed ‘Paint the Bridge’?

“Paint the Bridge,” a fall event where student clubs and orgs each painted a square on Washington Avenue Bridge, officially ended in 2021, just before Riesner enrolled. According to Student Unions and Activities, “Paint the Bridge” was created in 1997 as a campus beautification project. It doubled as an opportunity for student groups to promote their clubs.

But in recent years the event became a flashpoint for political conflict.

Officially, the decision to cancel “Paint the Bridge” was made by both SUA and Facilities Management so the university could begin maintenance work on the bridge, according to Garnette Kuznia, communications adviser of SUA.

But several well-publicized clashes preceded that decision. During Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, the U’s College Republicans club painted the slogan “Build the Wall'' on their designated bridge square. Protests ensued. Eventually, the panel was painted over with the phrase “Stop White Supremacy.” Every subsequent fall until 2019, the College Republicans’ panel was vandalized. In 2019, for example, the group painted their panel with “Keep America Great” and “Donald Trump The Wall.” It was vandalized with “White Supremacy Kills.” (Members of right-wing campus groups didn’t respond to a recent request for comment.)

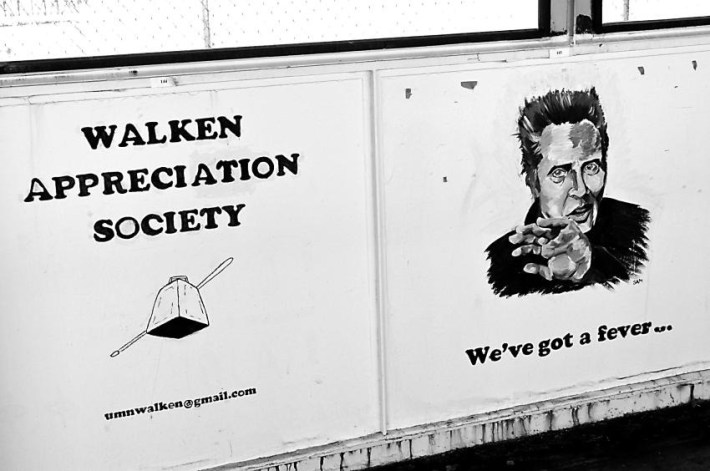

The controversy around the College Republicans’ panel stood apart from the other panels, where the paintings were mostly benign, according to Jane Kirtley, a professor of media ethics and law at the U; messages from sororities, the Minnesota Quidditch Club, and the Christopher Walken Appreciation Society don’t tend to elicit much blowback.

“Expressive activities take all kinds of forms,” Kirtley says. “I think it’s really unfortunate, both from the perspective of those who wanted to have a square on the bridge and also from the perspective of those who wanted to receive that information, that the university decided that would no longer be allowed.”

When asked by Racket last year if “Paint the Bridge” was squashed due to political controversy, a U of M spokesman echoed the “ongoing repairs and maintenance” line, noting that there are “not presently” plans to bring the event back. “‘Paint the Bridge’ was not developed as an added platform for informed debate in addition to the many existing opportunities for discussion and expression already offered at the U of M,” adds Kuznia of SUA.

Nick Hervatin, an alumni who was in the band fraternity Kappa Kappa Psi, helped paint music notes on a square his freshman and sophomore years. When “Paint the Bridge" was canceled Hervatin’s junior year, he assumed it was merely paused because of COVID-19. The outright elimination disappoints him.

“I do think the university has a lot of great resources for students to find community,” he says. “But ‘Paint the Bridge' was a way for new opportunities to be presented to students year-round.”

A Movement to Revive the Bridge

During a student government forum this past November, members of the Infrastructure Committee asked for a vote on a “positioning statement” to revive “Paint the Bridge.”

Students Ian Tripp and Leo Puntillo argued for the proposal, noting they were acting on behalf of students who responded via a survey that they want the annual event restarted. Because the university is such a large campus, they argued, an event like “Paint the Bridge” is even more important as “a means of outreach and community building,” Puntillo said, while acknowledging that there’s “inherent risk” for future tensions around it.

The GOP-shaped elephant in the room was vandalism. As Shashank Murali, student body president, put it, “The biggest concern is student groups might have aggressive acts against them… the negativity that affects the students in that group is really challenging to navigate.” Other concerns bubbled up at the forum, like equity: The 1,130-foot-long bridge does not have enough spaces to accommodate all the clubs at the university, provided each and every one wanted to participate.

The measure just barely failed, by a vote of 51 to 49. There will be a future opportunity to present a revised, more detailed statement on what a revitalized “Paint the Bridge” could become, Tripp says.

Yet Another College Campus Free Speech Fight

Undergraduate Student Government officials are currently consulting with university administration and various student groups on bringing back “Paint the Bridge,” reports Daniel Tobias, the director of the group’s Infrastructure Committee. “It’s really what student groups want, even now that they’ve had that experience with vandalism,” he says.

Whether people like it or not, speech that could be deemed hateful is protected by the First Amendment unless it can be legally proven as a “true threat,” says Kirtley, a media law professor. The College Republicans’ “Build the Wall” sloganeering can be interpreted as offensive to immigrants, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t protected speech, she explains, adding that she believes the elimination of “Paint the Bridge” generally inhibits student expression.

“There are plausible interpretations that see it as non-threatening, and there are also interpretations that see it as extremely threatening,” Kirtley says. “That doesn’t mean it should be banned as an expression, but, to me, that’s the kind of thing that has an ambiguous meaning—if it’s ambiguous, it should be protected. If we really believe in a diverse university, which is what the University of Minnesota always says it is, then they have an obligation to mean it and say, ‘Yes, we include not only diversity in terms of race, gender and ethnic origin, but also diversity of thought.’”

Shortly after he transferred to the U, Riesner ended up joining two student organizations—lefty political org Students for a Democratic Society and the Undergraduate Student Government. He recognizes SDS’s panel might get vandalized if “Paint the Bridge” returns, but says it’s well worth the risk.

“The remedy for hate speech is not to tear it down, blot it up, paint over it, or blow it up,” he says, “but to counter it with better speech.”