There’s an odd dance going on in the Minnesota legislature this spring, as lawmakers in St. Paul tackle what they say is a literacy crisis of third graders not reading at grade level.

Their solution to this suddenly discovered emergency—an ongoing problem for 30 years—is to embrace an academic and media fad called the “Science of Reading” (SoR). Key players behind the push include private-equity companies that are keen to cash in by selling teacher training and curriculum products, and radio reporter Emily Hanford, a phonics fabulist who works for American Public Media (the corporate parent of Minnesota Public Radio) and whose popular podcast, Sold a Story, is a hard sell for SoR. The legislation currently before the Minnesota House is larded with “must”-do mandates. It would effectively outlaw an approach long used to teach many Minnesotans to read, and replace it with a drill and kill curriculum which critics say will cause many students to hate reading.

The Science of Reading is not actually a science. It is phonics fundamentalism that ascribes virtually all reading failure to flawed curriculum. And like most fundamentalist creeds, SoR has zeroed in on a villain: an unscrupulous literacy education establishment that ignores science and insists on clinging to outmoded models. For parents, politicians, and other education stakeholders frustrated by the reading woes of some students, the simplicity of the SoR holds an obvious appeal; we can radically improve academic performance by tinkering with curriculum mandates, proponents argue. Unstated in the rush to embrace SoR is a more complicated reality. In fact, the core tenets of SoR are unsupported by some research and unlikely to move the literacy needle much, if at all.

Debunking the Science of Reading is not hard. After all, if associating sounds with symbols was the only way people learned to read, then no deaf person would be able to read—nor, for that matter, would 1.4 billion people in China, as Chinese is a non-phonetic language. Truth is, tens of millions of people around the world learn to read every year without phonetic instruction. Science of Reading boosters love to claim that recent advances in brain science prove their theory. When asked in January by Racket for proof of this assertion, Hanford pointed to the resources page for her stories, which includes just one 13-year-old book on brain research. (She declined further comment this week.) Given the pace of brain research, a book that old is about as reliable as a 13-year old-book on the current state of research into artificial intelligence.

“Neuroscience research is about neural phenomena, not about the macro-level behaviors that are being used as variables in the [SoR] studies,” explains George Hruby, a national literacy scholar at the University of Kentucky. “These brain studies are not really 'about reading,' and thus they cannot prove anything about how to teach kids to read; they are about the biological, physiological, and anatomical structures, and processes of the brain.”

Legislating Literacy Curriculum, Training Based on a Hoax

The current campaign by the SoR crowd isn't rooted in literacy education, but rather is an extension of an attack on schools of education that began in earnest in 2000 when the leader of the education reform movement, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, launched a think tank called the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ).

A principal goal of the NCTQ is to discredit schools of education in order to create new, “alternative” paths to teaching, which includes licensing Teach For America recruits, who enter classrooms with only weeks of instruction. The schools’ supposed weak support of phonics was originally just a path to this goal, but the tactic has now taken on a life of its own.

The federal bipartisan No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 tested this theory with a $6 billion appropriation for phonics-intensive curriculum. Called the Reading First program, it was riddled with corruption and failure. But even this wasn't enough to put to rest the notion that the problem with primary education is schools of education and the teachers they educate. In the ensuing decade both the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the St. Paul-based Bush Foundation launched expensive, long-term attacks on public schools of education and public school teachers, and both predictably failed.

In 2013, NCTQ reignited the Reading Wars, this time publishing “ratings” of teacher education schools that ranked almost all of them negatively. At the time a distinguished group of Reading Hall of Fame educators and researchers called out the rankings, primarily because they did not “... consider the actual quality of instruction that the programs offer, evidence of what their students learn, or whether graduates can actually teach.”

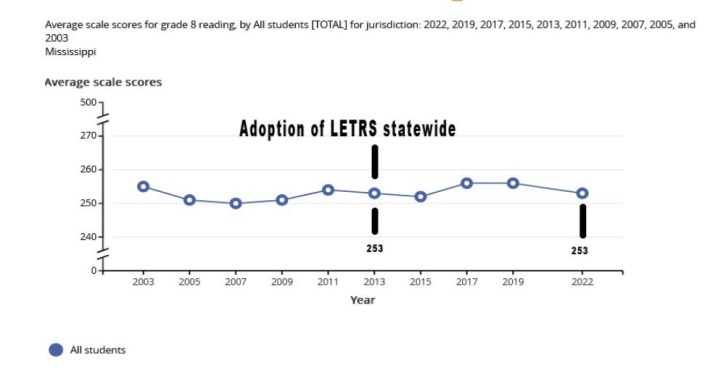

Since then 29 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws either partly or wholly based on the Science of Reading. The deluge started in 2013, when Mississippi passed a series of education laws that required, among other things, the statewide take-up of LETRS, a commercial teacher training program owned by the private equity company Veritas Capital. Touted as the Science of Reading, LETRS is really just a phonic fundamentalist approach to teaching reading. Mississippi provided an inviting natural experiment, and in subsequent years the state actually did have increases in fourth grade reading scores. Hanford of APM/MPR seized on this fact in a 2019 LETRS victory lap on the New York Times op-ed page. Her story, written in the polemical style she has since become famous for, is based on unfounded inferences and ignored confounding variables. In a word, it's nonsense.

But those increases don’t tell the whole story. As part of its education reform laws of 2013, Mississippi also mandated the retention of more third graders than any state in the nation. If you take your lowest scoring third graders and put them through third grade again, of course reading scores for fourth graders will go up, as the leading right-wing education think tank also wrote in 2019.

In fact, NAEP math scores also went up after the 2013 law was passed. Did LETRS cause math scores to go up for fourth graders in Mississippi? As others have written, Hanford routinely fails to address research that conflicts with her narrative.

And even if you thought that LETRS had something to do with elevating fourth grade reading scores in Mississippi, by eighth grade any gains were gone:

The Hoaxer and the Hoaxed

Minnesota has had its own brushes with LETRS, first in the 2021 legislative session, where Republican control of the Senate forced a compromise that included $3 million specifically and only for LETRS. In the non-budget year of 2022, still with divided government, Republican chair of the Senate Education Finance and Policy Committee Roger Chamberlain proposed no new spending on education except for $30 million for LETRS. That proposal (like virtually everything else in the session) went nowhere. The current proposed legislation to enshrine SoR into state law is called the Read Act, authored and carried in the legislature by Rep. Heather Edelson of Edina (DFL-Edina).

Early versions of the act included 11 direct references to the “Science of Reading,” and an appropriation of $100 million for teacher training and the purchase of learning materials based on it. But as the bill journeyed through committees, all references to the Science of Reading vanished, most replaced by the phrase “evidence-based.” That sanctifying term is invoked 46 times in the current version of the bill.

Why was this language changed? “Science of Reading was removed and replaced with Structured Literacy which is the application of the Science of Reading,” Edelson tells Racket, declining further comment.

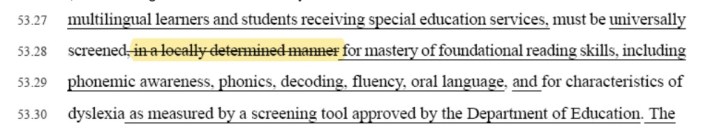

The bill itself is a giant middle finger to teachers, districts, and schools of education. It repeatedly takes decisions about curriculum, teacher training, and testing away from local control and imposes myriad burdensome mandates. It contains a built-in conflict of interest where the institution required to approve training and curriculum programs is allowed to include ones it sells. The bill requires a slew of new testing, including requiring schools to test all students in grades K-3, with a state-approved “screener,” for reading deficiencies twice a year.

There are changes that take away local control, like the one highlighted above in the Senate Omnibus Education Funding bill, throughout the Read Act.

The bill also requires anyone who teaches reading in public schools to be trained in the Science of Reading. At the same time, it prohibits current methods that have been used to teach many Minnesotans to read for decades. It does this by liberally sprinkling the phrase “evidence-based” throughout the bill's text, and then provides the following as part of its definition: “Evidence-based instruction does not include the three-cueing system.” Just what is this horrific thing called “three-cueing”? Synthesizing meaning, structure, syntax, and visual cues to figure out word meaning is what other people call “thinking,” but what Rep. Edelson and her bill would specifically prohibit. And the part of the bill requiring this teacher training is not optional.

Most of the mandates include funding for a year or two, with no guarantee of funding from future legislatures. Put another way, the Science of Reading could easily become just another unfunded mandate for public schools, which already bear a $1 billion a year cross-subsidy for Special Education and English Language Learners.

On the carrot side, the bill provides for $40 million in one-time money for districts to purchase approved training and curriculum. Though the use of these materials isn't required by the legislation, $40 million is a lot of money and most districts and charter schools will undoubtedly feel compelled to apply for it. But the bill is silent on what happens when this fund runs out. Undoubtedly, owners of the few approved curriculum and trainings—like Veritas Capital's LETRS—will demand their annual fees. Will the Read Act just turn into another unfunded burden for school districts, many of which are already on the cusp of a fiscal death spiral?

MN Dept. of Education's Foray Into Prescribing Specific Training, Curriculum

Which brings us to the most curious part of this bill: It mandates that districts “...provide training from a menu of [three] approved evidence-based training programs” to basically anyone who teaches reading in any way.

So for the first time ever the Minnesota Department of Education would mandate the use of particular teacher training and curriculum. And the institution designated to approve those programs, the Center for Applied Research and Educational Achievement (CAREI) at the University of Minnesota, has a glaring conflict of interest in this pursuit: It has recently begun selling its own teacher training/curriculum which it claims is aligned with the Science of Reading.

CAREI Director Kim Gibbons said in a phone interview that the Center's Science of Reading implementation, called Functional Phonics, wouldn't qualify for reimbursement under the Read Act because their program is not a “comprehensive, universal curriculum.” The phrase does not appear in the Read Act, and the webpage for Functional Phonics describes it as “...a comprehensive, evidence-based curriculum...” So… just missing the “universal” part. And since CAREI is the institution deciding who gets paid, it could just add the word “universal” and approve its own product–it even says so in the proposed law.

The direct grant of $4.2 million CAREI receives under the Read Act does not include any money appropriated for teacher training or curriculum under the bill. It's just for helping the state implement it.

The Read Act Is Big Doings

The Read Act envisions huge changes for teaching reading in Minnesota. It sets a new precedent of the state both prescribing certain kinds of teacher training and proscribing others, it requires new testing and reporting, and it bans teachers from using a method of teaching used successfully for decades. Rep. Edelson told her own constituents, without hyperbole, that her bill “...massively overhaul[s] how we teach literacy in Minnesota...”

Despite this proposed revolutionary change, the hearings for the Read Act in both the House and Senate suggested that the outcome had long ago been decided. Testifiers seemed to try to outdo each other in their race to utter the phrase “Science of Reading.” And even though the phrase “Science of Reading” had been taken out of the Read Act, the code words within the text signifying the same thing remain: “evidence-based,” “structured literacy,” “systematic phonics.” And they know their hated bête noire, “three-cueing,” has been banned.

But there's a hidden weakness in the SoR argument here in Minnesota this year: The Read Act is the Science of Reading Act, but supporters won't say that. It seems they fear an airing of their foundational claim, that they and they alone hold the keys to the one true “science” of reading.

Many Science of Reading true believers either have kids, or know kids, who could be better served by our public schools. But the causes of reading struggles are much more complicated than our all too usual blame-the-teachers reflex. And the solutions do not lie in adopting authoritarian teaching techniques and writing giant checks to private equity. There's also nothing intrinsic about the levels we set for various standardized tests whereby we label children as “not proficient.” Children are unique beings who learn at their own pace. Even testifiers at Rep. Edelson's hearings agreed that the MCAs—Minnesota's standardized tests used to assign these labels—just aren't that useful.

It's also disappointing how Science of Reading advocates single out reading as the one thing they want to improve in our public schools. They seem to ignore that proficiency gaps exist in other tested subjects. These gaps are not the fault of teachers, schools, districts, or schools of education, as the SoR advocates love to assert. They are the product of a racist and classist society, and of literally decades of under-funding public education in Minnesota. There are proven ways to increase educational attainment across the board, common sense —but expensive—measures such as decreasing class sizes and providing universal Pre-K. But none of that gets a mention in the Read Act.