This post originally appeared on Anders Lee's Substack.

My family moved to Minnesota in 2003, the year that state’s politics became boring again. Jesse Ventura had moved out of the Governor’s Mansion and a sense of melancholy hung in the air around Paul Wellstone, Minnesota’s second-least orthodox politician, who had tragically died in a plane crash—along with his wife, daughter, and three campaign staffers—less than two weeks before the 2002 election. I didn’t become aware of Paul and his wife Sheila until after they were gone. Green “Wellstone!” signs stood on the lawns of what felt like every other yard in our new neighborhood of Cathedral Hill, where the Wellstones had lived out their final years.

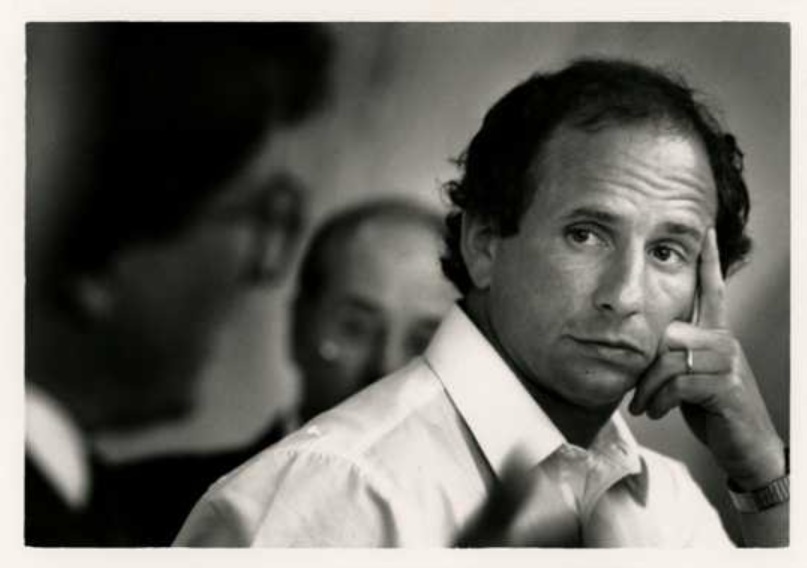

It took awhile for me to really understand what set Paul Wellstone apart from other senators and politicians and what made his death so painful, often on a personal level, to my new neighbors. Footage of the late senator shows the level of sheer passion he had for justice and life itself. Wellstone more than made up for his short height with his charisma, loud voice, and ebullient personality. There are few people for whom the word “pugnacious” has been deployed so frequently. He served through the Clinton era, when the president had made glad-handing an art form. But, whereas Slick Willy would “feel your pain” in one room and cut your benefits in the next, Wellstone actually fought for the people he made it a point to always greet and remember. No Jedi mind tricks are needed when you actually give a shit.

Wellstone served as a friendly ghost as I developed politically in my teenage years. My first job was at a video store on Selby Avenue, where Paul and Sheila had been customers. (For the record, the last movie they rented was Bandits with Bruce Willis and Billy Bob Thornton.) There I watched documentaries about figures like Ralph Nader, Noam Chomsky, and this one about Wellstone himself. Eventually, I wound up a Marxist, which Wellstone was definitively not. Son of a Russian émigré who wrote anticommunist propaganda for the Voice of America, Paul often invoked the Soviet Union in typical Cold War caricature as a dystopian hellscape. He was deeply patriotic and a self-described liberal. In Wellstone’s time, however, these differences were more or less immaterial. Ideology aside, Wellstone was a significant departure from his fellow Democratic electeds.

Wellstone first won in 1990, narrowly unseating out-of-touch incumbent Rudy Boschwitz in what many considered a fluke. Six years later, when Rudy wanted his job back, the common wisdom would have had Wellstone triangulating along with the White House, latching himself to Republican ideas to hold on to power. Regrettably, Wellstone did vote for the Defense of Marriage Act that Fall, but stuck to his guns on one of the '90s most hot-button issues: welfare. Indeed, Wellstone defied Clinton on a whole suite of policies including NAFTA, GATT, NATO expansion, and deregulation of the financial and telecom sectors. In his election year votes against welfare reform and the Iraq War—the only senator up for reelection to vote against either—Wellstone flouted the Democratic Party’s iron aversion to standing on principle at political risk.

A veteran of the 1960s New Left and later the 1980s Rainbow Coalition, Wellstone represented an alternative course to the Democratic Leadership Committee, whose overtures to “electability” always magically line up with the desires of corporate America. One of very few bonafide progressives to make it to the senate post-Reagan, Wellstone openly considered a presidential candidacy in the late '90s. He decided against it for health reasons and, lacking any better option, threw his lot in with former senator and basketball star Bill Bradley’s primary challenge to Al Gore for the 2000 election. Bradley was a steadfast advocate of campaign finance reform, but an enthusiastic booster for the status quo on the late '90s other hot button issue: trade—aka “globalization.” It would have been a nearly impossible feat for any Democratic challenger to best then Vice President Gore. But a Wellstone candidacy would have at least tested the allegiances of organized labor, heightened the contradictions between leadership and the rank and file.

The real difference between Bradley and Wellstone wasn’t a narrow policy distinction, however. It was in their approach to politics at large. Wellstone was the product of movements. The purpose of his hypothetical presidential campaign wasn’t just to win, but build a grassroots machine. A progenitor of Bernie Sanders and his national campaigns, Wellstone was able to win statewide race; something that eludes today’s Democratic Socialist movement, aside from Bernie, of course. After the deaths of Paul and Sheila, the group Wellstone Action (now called Re:Power) was formed to train not only progressive candidates, but organizers as well. Ultimately I’m glad we have Democratic Socialists of America, a distinctly socialist organization, that coordinates hundreds of electeds and tens of thousands of members nationwide. But a similar structure with a broader base is a welcome thought, at least to me, looking back on the dull and dismal political landscape at the turn of the millennium.

Wellstone’s persona and the tragedy of his death are the things remembered in Minnesota ahead of his beliefs and political vision. He was counted as the political hero of Al Franken, who avenged Wellstone’s U.S. Senate seat in 2008, inspired by this insensitive comment from Paul’s successor. There are certainly worse Democrats, but during his time in the senate, Franken held no candle to Wellstone in his willingness to buck leadership and, awash in money from Hollywood, had little interest in building the same kind of small-donor funded movement Wellstone did. Speaking of worse Democrats, the appropriation of Wellstone’s legacy by Minnesota’s senior senator, Amy Klobuchar, is more offensive to me than any of the crude conservative responses to his death—this includes my friend’s dad who bought a bumper sticker reading “Wellstone! Is dead. Get over it.” Paul Wellstone, for the entirety of his time in public life, championed a Medicare for All-style, single-payer health insurance system. He almost definitely would have been a loud supporter of the Green New Deal. To premise your presidential campaign against both of these things using a logo explicitly modeled after Wellstone’s, is to projectile vomit kelly green puke all over his legacy.

At the time of his death, Paul Wellstone had been pulling ahead in the polls despite a controversial vote against the Iraq War. A Wellstone reelection would have denied Republicans a unified government—both houses of congress and the presidency. The pugnacious senator from Minnesota was poised to be a serious thorn in the Bush administration’s side as they prosecuted the war, especially given his vocal opposition to military contractors. Three months before his death, Senator Wellstone had inserted an amendment into the Homeland Security Act barring tax dodgers from receiving Defense Department contracts. After his death, it was jettisoned. Bush, Cheney, and their motley band of thugs stood in direct opposition to everything Paul Wellstone believed. Reportedly, Cheney even said to Paul, “If you vote against the war in Iraq, the Bush administration will do whatever is necessary to get you. There will be severe ramifications for you and the state of Minnesota.” Unfortunately, inquiry into the deadly northern Minnesota plane crash itself has been tainted by its lead investigator. Nonetheless questions remain: Why did the plane have no black box? Did witnesses hear gunshots near the crash site? We’ll likely never know.

Over the course of his life, Paul Wellstone’s core conviction was that politics wasn’t money and power but improving people’s lives. In his words, he didn’t want to be a senator for the drug companies or the tobacco lobbyists because, “they already have great representation. I want to be a senator for you.” When you’re a political person, it can be tempting to think of yourself and whatever movement you belong to in grand, historical terms. To a large extent that’s important. But, as Wellstone believed, that’s not all politics is about either. As he’d often say, it’s “about doing well for people.” No better way to remember him than trying to do that.