The Mighty Ducks trilogy. The Grumpy Old Men duology. The Drop Deads (Fred and Gorgeous). Fargo and A Simple Plan. Little Big League and Major League: Back to the Minors. The Good Son, The Naked Man, Angus, and Mallrats.

Those are just 15 of the 62 movies filmed in Minnesota in the 1990s. This was the golden era for the Minnesota Film Board, a nonprofit founded with the goal of wooing production companies to Minnesota. If those companies were game, the Film Board would help with location scouting, securing filming permits, and hiring in-state castings and crews.

The board was formed in 1983, following a push from Gov. Rudy Perpich and MN Rep. Richard Cohen, a fairly new state representative who would go on to serve 34 years on the state Senate. As a nonprofit, half of the Film Board’s funding came from state appropriations, with the other half coming from companies like Northwest Airlines, Target Corp., Best Buy, and various hotel chains—places that stood to benefit from productions setting up shop in Minnesota.

Thanks to the board, Minnesota managed to land a few movies in the second half of the 1980s, including That Was Then… This Is Now, a coming-of-age story based on an S.E. Hinton novel starring Emilio Estevez, and Youngblood, a hockey flick with Rob Lowe and Patrick Swayze. But things really took off in 1990 when the board got a new director, Randy Adamsick.

“He was a visionary in what he did,” says Cohen.

“He was the battery, man,” adds filmmaker and storyboard artist J. Todd Anderson.

For one of his first moves as director, Adamsick ventured out to Los Angeles, setting up a booth at a state film commissions conference. That’s where he met Donna Smith.

Smith was Universal’s president of physical production and post production—the first woman to hold such a title at a major studio. But she was very familiar with the Twin Cities, having started out as an administrator at the Guthrie.

Smith explained to Adamsick that the board was targeting the wrong people.

“She basically said—she used such a Minnesota word—‘What’s wrong with you ditzes?’” Adamsick remembers.

“It’s not the people who decide what movie is going to be made that they should be talking to,” she told him, “but the people who decide where the movie is going to be made.”

Smith stayed in touch, using her connections to help the board land previously unbookable meetings with executives. Adamsick also started making regular trips to Los Angeles, where he would network at “Ice Pack” meetups, parties for Minnesota transplants in Hollywood. There he met people like producer Patrick Wells, who told him there were only 20 questions production heads would ever ask him about filming in Minnesota.

A few guarantees: What locations do you have? What kind of crew do you have? What actors do you have? What equipment and supplies do you have for filming?

“He was absolutely right,” Adamsick says.

But Adamsick wouldn’t have brought in $150 million for the state if he hadn’t had good answers to all of those questions.

Of course, because it’s Minnesota, Prince was a part of those answers.

The Prince Factor

The rise of the film board “basically paralleled the making of Purple Rain,” says Tim Campbell, the Minnesota Star Tribune’s former arts editor.

Purple Rain was filmed in 1983, the same year the board launched, and when it came out the following year, it gave Prince the money and the power to build Paisley Park.

In a 1987 cover story for the Twin Cities Reader about Paisley Park’s opening, Martin Keller wrote that the facility had “a 12,000-square-foot soundstage, the largest between New York and Los Angeles,” as well as “the most massive film and TV lighting and rigging assembly available statewide.”

At the time, Adamsick’s biggest—though not only!—selling point was that we had plenty of snow. Thanks to Paisley Park, movies that needed outdoor snow shoots, like Grumpy Old Men, could now also film their interior scenes in Minnesota as easily as they could in Hollywood.

Eric Howell was living on a houseboat when location scouts for Drop Dead Fred checked out his residence. He leveraged that meeting into a job on the film, and later ended up taking on a variety of roles at Paisley Park.

“I would be rigging [Prince] in a harness to fly from the stage and then, before you knew it, I was pushing a camera dolly or I was helping build a set,” he says. “[Paisley Park] was just one of these places where you started learning all sorts of stuff.”

When Hollywood came to town, it created more job opportunities for Minnesotans working in film, as talented local crews would be hired to take on successful productions. That led to more productions coming to town, which led to more jobs, and so on.

Howell, for instance, got consistent work as a stuntman, learning enough from the California crews to eventually become a stunt coordinator.

Paisley Park would also connect Minnesota to bigger studios. When Prince’s palace opened in 1987, Harry Grossman was the head of studio operations there. In 1989, he left for an executive position at Disney. Without him, Minnesota may have never landed the Mighty Ducks trilogy, a series that had one of the biggest budgets of the Minnesota movie boom, and served as an early showcase for the state’s film economy.

Sustaining an Infrastructure

As fun as it is to credit Prince with creating all the jobs for the state’s key grips and best boys, Minnesota was also already a hub for industrial videos, commercial shoots, and home shopping television networks like ValueVision. Those types of projects weren’t nearly as glamorous as a major Hollywood film, but they did provide consistent work, practice, and pay for crews so talent could remain in the state.

The Twin Cities theater scene was also thriving, as the Guthrie Theater, Park Square Theatre, Brave New Workshop, the Jungle Theater, Chanhassen Dinner Theatres, and others made the Twin Cities a premier destination for actors. Having great actors in town meant productions could save money in casting.

The Naked Man was directed by J. Todd Anderson, the Coen brothers’ longtime storyboard artist (he also had a small role in Fargo as “victim in the field”). While he had originally planned to shoot it in Ohio, he chose Minnesota because “the talent I was looking at at the time in Cincinnati just wasn’t cutting it,” he says.

Jim Cada worked on movies in and around Minnesota in the ’70s and ’80s, but his career really took off in the ’90s, when he appeared in seven locally shot movies. “I was working like crazy,” he says. “I was doing indie theater or films or voiceovers for commercials. I mean, [Minnesota was] a great place to be.”

John Carroll Lynch, who was working at the Guthrie when he scored first film role (“moving man” in Grumpy Old Men) would become a well-known character actor after playing “Frank Womack” in Beautiful Girls and Norm “Son-of-a-” Gunderson in Fargo.

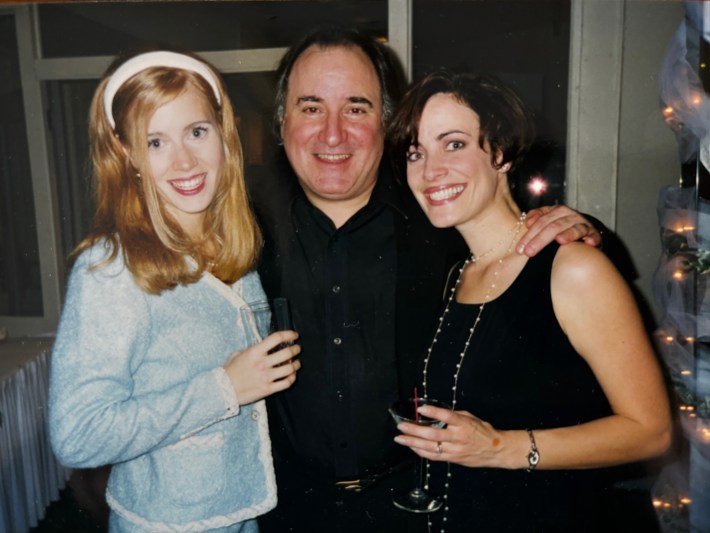

Amy Adams, who starred in several Chanhassen Dinner Theatres productions in the ’90s, made her big Hollywood debut in the Minnesota-made Drop Dead Gorgeous.

“I truly believe I would not be where I am,” she told Racket when asked what her life would be like if CDT’s longtime artistic director Michael Brindisi hadn’t plucked her out of the Colorado theater circuit. “I know that sounds like a big statement, but there’s so many [things], not only the opportunities that were held in Minneapolis, but the family and the community. I don't think I would have had the confidence to move to L.A. without the experience of CDT, and knowing that I truly believed I always had a home to go to.”

Mo’ Money Mo’ Problems

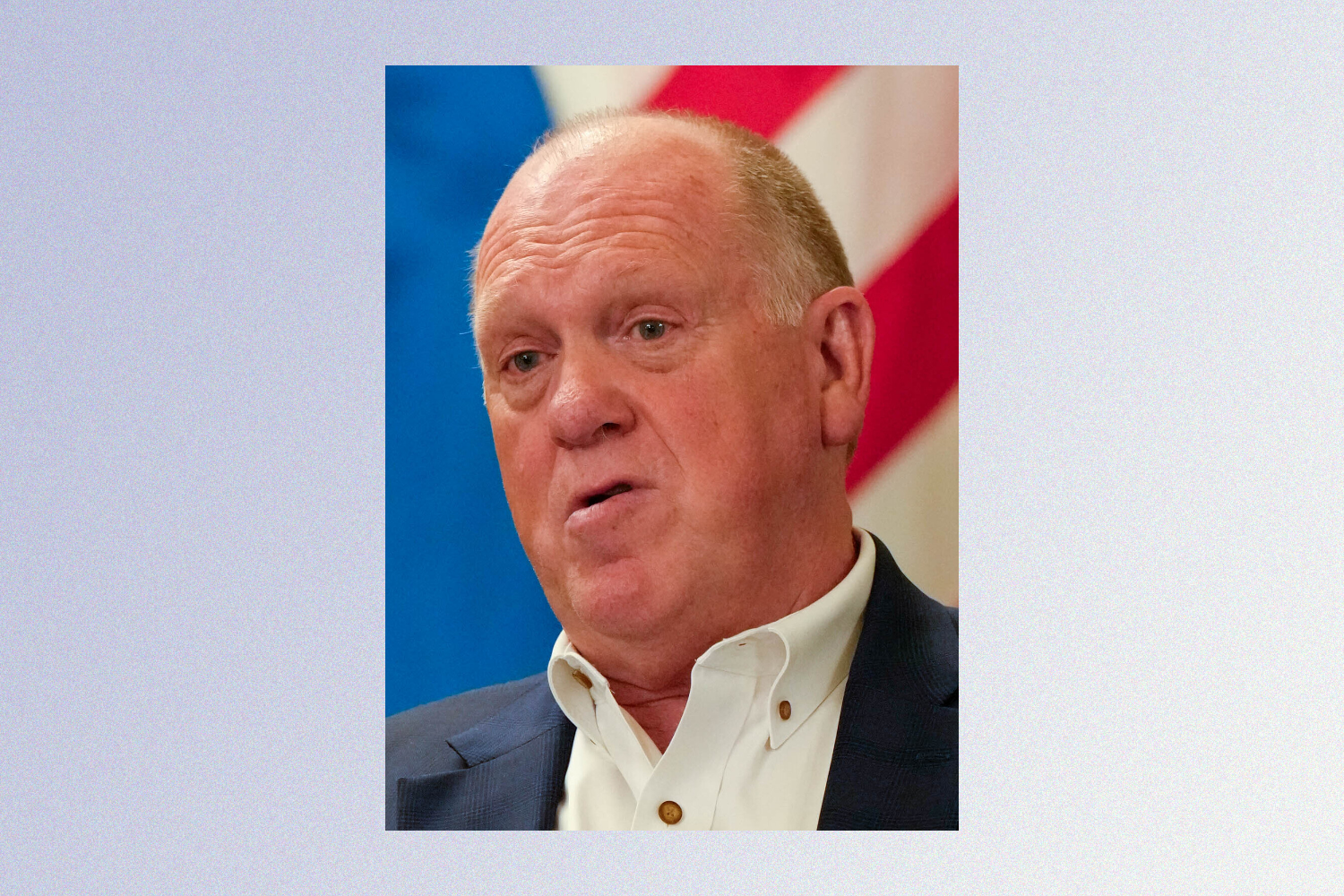

In 1991, less than a decade into the board’s creation, Governor Arne Carlson felt it had matured enough that it could support itself.

“When I came into office, we had this massive deficit,” Carlson told Racket in 2021 of his first legislative session. “So I wanted to go through every line of the budget and veto everything. So, bingo, I put a red line right through [the MN Film Board]!”

Disheartened, Adamsick began looking for new allies. “We turned to the news, because they viewed us as their peers,” he says

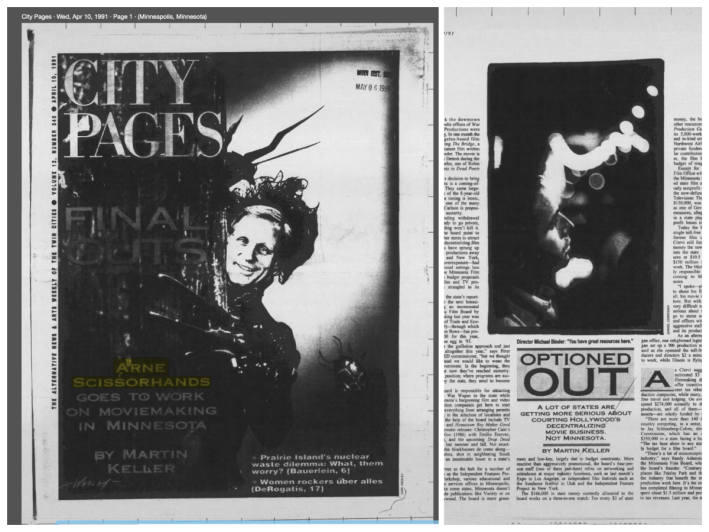

He contacted pop-culture journalist Martin Keller, who’d already written about how great Paisley Park could be for local movies for the Twin Cities Reader, and he ran with it. “I just started calling film commissions around the country,” Keller remembers.

What he found was that privately funded film boards didn’t work; movie producers trusted government-backed boards more, and government boards had better success pushing for more money if needed.

Cohen, by then a Minnesota senator, argued that film board appropriations made back eight times more for the state, almost entirely from out-of-state companies. In other words, the board was bringing in enough money to pay for other government programs.

Then came Keller’s “Arne Scissorhands” City Pages cover, designed by artist Carl Wesley, which featured Carlson’s face pasted over Johnny Depp’s iconic character. “I heard almost immediately when it hit the street that the governor went apeshit,” Keller says.

It all set Carlson on the road to becoming the board’s strongest supporter, bolstered by a starstruck trip to the Grumpy Old Men set. Government appropriations were never questioned again under his administration.

“[The media blitz] saved the day,” says Adamsick.

But there were other problems. By 1995, just as the board was landing bigger budgets and hipper projects—Jingle All the Way, Mallrats, Fargo, Beautiful Girls—Canada had introduced a national tax credit for film productions. Add to that a favorable exchange rate and equally snowy weather, and Canada had a lot of appeal.

While some filming locations in the states were impacted by this, Minnesota’s combination of cold, a nice soundstage, and local professionals kept it in competition with Toronto and Vancouver.

In 1996, State Senator Cohen introduced the Minnesota Film Jobs Fund, a 5% tax rebate for productions that hired local crews, and in 1997 he introduced a program known as “Snowbate,” which refunded 10% of production taxes to the production company, up to a maximum of $100,000.

These helped keep Minnesota in the game, but Canada kept poaching movies.

When Jesse Ventura became governor in 1999, his celebrity cachet helped Adamsick get a few more meetings with stars, including a dinner with Jack Nicholson and Sean Penn at the Governor’s Mansion. But schmoozing wasn’t enough to keep a steady run of productions.

“Canada was killing us,” says Adamsick.

While a few big stars and big budgets have come through town over the past 25 years, including pics like A Prairie Home Companion, A Complete Unknown, Factotum, and A Serious Man, nothing has even come close to approaching that ’90s boom.

Cohen remained an advocate for film in the state until he left office in 2021, but funding and tax rebates have fluctuated greatly over the years. In 2024, the Minnesota Film Board closed in favor of the fully government-funded operation Explore Minnesota Film.

Minnesota is not the only state to lose movie deals to foreign markets. As Trump threatens to annex Canada he’s also suggested what would be an industry-ending 100% tariff on Hollywood movies made outside the U.S. Meanwhile, a more rational Sean Astin, who is currently SAG-AFTRA’s president, has said that he wants to find new ways to incentivize domestic production.

As for Minnesota, we still have snow, Paisley Park, and a strong local theater scene. And in recent years Duluth has hosted a flurry of film crews, including ones for a Hallmark Christmas movie, a Hulu romcom, and a beauty pageant thriller. Maybe someday we’ll see another true Minnesota movie boom.