“We’re looking to stem the tide of streaming.”

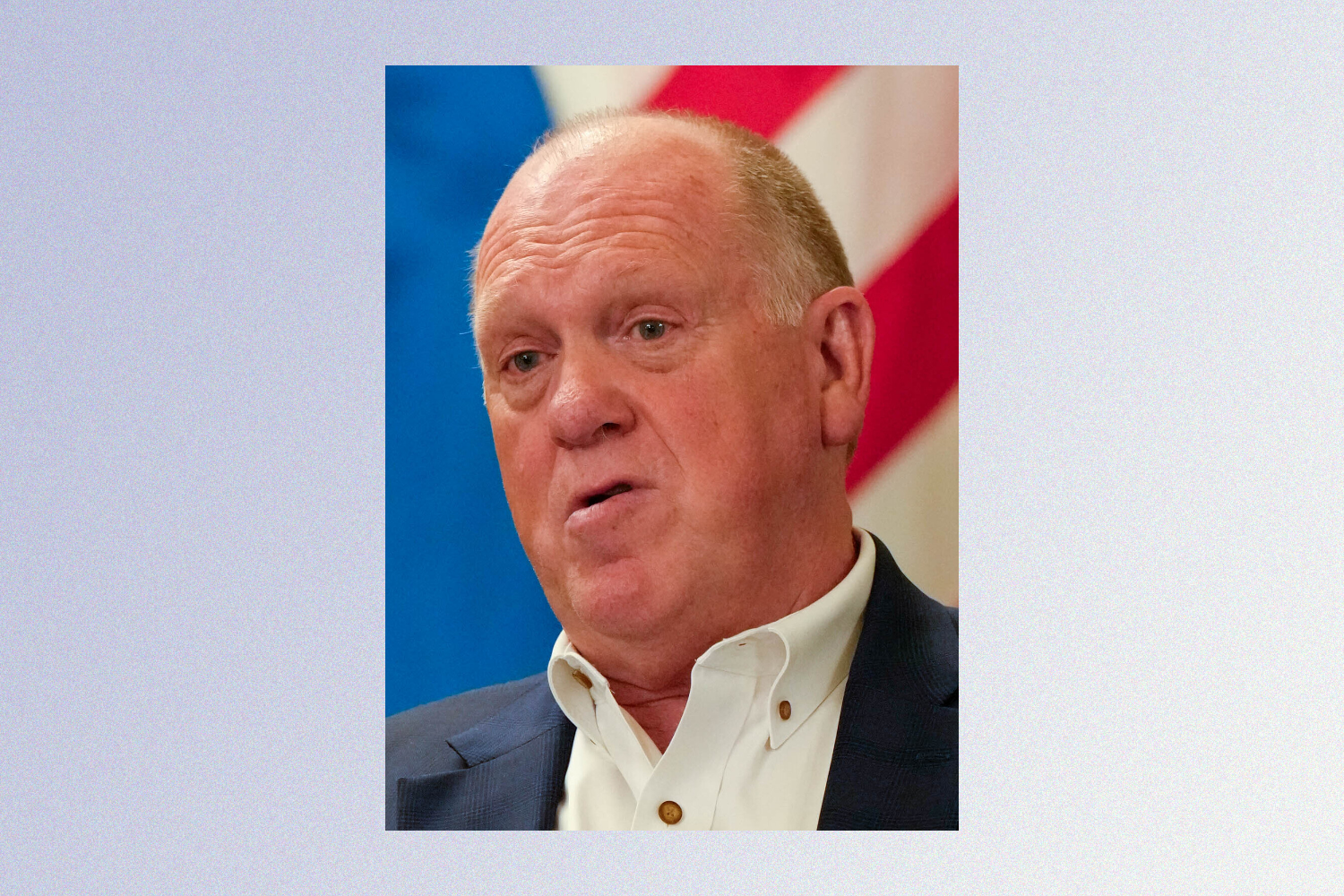

That’s how Ward Johnson, co-owner of the Parkway Theater, describes his goal when programming movies.

We all know the complaints. The average home viewer is probably watching a TV show instead of a movie, and their eyes are just as likely on their phone as their TV. And if they are watching what’s on TV, it's something algorithmically suggested to keep them subscribed and binging.

If you’re looking to snap out of the perpetual menu scroll, there are a lot of great independent movie theaters around the Twin Cities. The Main Cinema hosts the massive Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival and screens many other series you can’t find anywhere else, while the Riverview shows first- and second-run movies.

And four of those theaters—the Parkway Theater, the Trylon, the Heights Theater, and the Walker Art Center—aren’t just programmed by humans rather than algorithms; they also show a selection of their movies on film, rather than digitally, to deepen the viewing experience.

Racket spoke to the programming powers at each theater to learn about how they do their jobs, and to get the ball rolling we asked each the same question: What would be a good example of a journalism movie you’d screen at your theater?

“The first one that would come into my head is All the President’s Men,” Trylon programmer John Moret says. “But I would probably want to pair that with something that’s maybe a little more off-the-cuffish.”

The Parkway’s Johnson says he probably wouldn't screen All the President’s Men, “because it’s not fun.”

Tom Letness, owner of the Heights, says His Girl Friday. Peter Schilling, an unofficial promoter of The Heights who helps with programming, first said Citizen Kane, before adding that All the President’s Men would work too.

Pablo de Ocampo, Director and Curator of Moving Image at the Walker Art Center, couldn’t come up with an answer. He just laughed.

Johnson can remember where he first saw the movies of his childhood—Star Wars at the Hopkins Theatre, The Empire Strikes Back at the Southtown Theatre, Return of the Jedi at Ridge Square 3. Now when he picks a movie he wants to give his audience “that feeling of what it was like to see it on the big screen for the first time.”

He mostly screens 1980s movies at the Parkway, but stretches a decade or two in either direction, and likes to keep it lighter and more accessible with comedy, action, and horror. (As we discussed journalism movies further, he settled on Superman and Superman II with intrepid reporters Clark Kent and Lois Lane, both of which he’s shown before, as the his theater's spin on the genre.)

Johnson, who bought the Parkway in 2017 with business partner Eddie Landenberger, has kept the south Minneapolis theater from 1931 looking like its historic self. “We have the original seats in there, so we’re probably not as comfortable as your reclining La-Z-Boy theater,” he says. And in the Parkway’s Art Deco lobby you won’t buy tickets at a computer kiosk or pour your Coke from a touch-screen.

The Parkway also makes moviegoing an event. The theater often hosts trivia, live music and comedy, or even movie-themed poetry contests before a screening. In October, people in the lobby dressed as that night’s horror movie characters to set the mood.

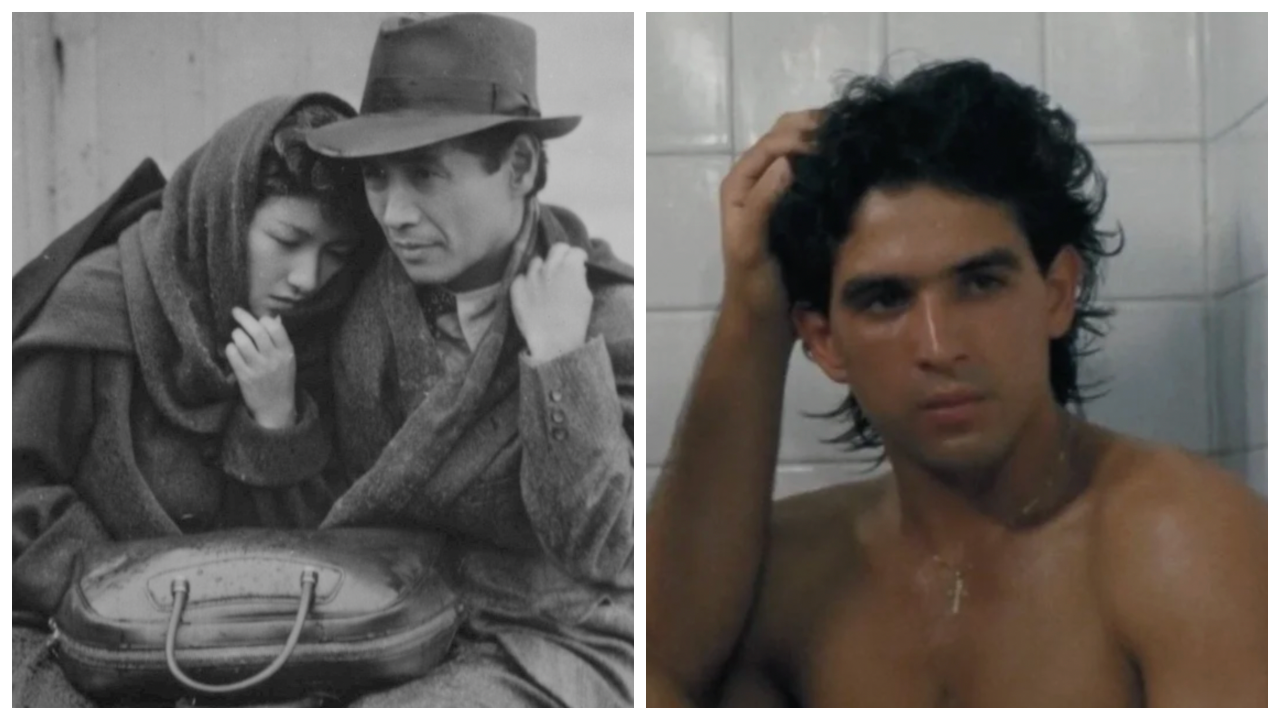

The Heights, as Letness and Schilling’s journalism movie picks might suggest, is more focused on Old Hollywood, screening more black-and-white movies than anywhere else in town. Their big events are built around older movies too, like their yearly Hitchcock series and White Christmas screenings.

“It’s the whole experience, it’s the package,” Letness says of how the programming matches the building. Built 99 years ago in Columbia Heights, the Heights still maintains a century-old look. An organ from 1929 plays before films, and can be used to accompany a silent movie.

Where those two theaters spin their experience around the feeling of going to a movie, the Trylon and the Walker are more like film school, introducing people to what movies can be.

When the Trylon's Moret said he would need to provide a second movie to go with All the President’s Men I suggested Between the Lines, the 1977 movie about a struggling Boston alt-weekly (featuring a young but fully self-actualized Jeff Goldblum), and he agreed.

That combo would be an example of Moret’s programming process in Minneapolis's Longfellow neighborhood, which, he says, starts with the question: “What’s the movie I really want to show that generally people aren’t going to come buy tickets for?”

Then he asks, “What can I surround this movie with that’s going to pay for it?”

“What I’m hoping,” he explains, “is that people want to see movies they love again, and then that draws them to something else that’s new to them that they can fall in love with.”

Similarly, de Ocampo, who took over as the Walker's Moving Image Department curator in 2021, says, “I don’t think about ‘what’ the Walker is showing as the organizing principle, but ‘how’ and ‘why.’” Like the rest of the famed Minneapolis museum, he says, the department is “artist-forward.”

That’s why he laughed when asked about journalism movies. Everything is on the table.

“I don’t really know why we would ever show those,” he says of the obvious choices, “but I could totally also see this scenario where an artist might come to the cinema that might have nothing to do with journalism altogether, but be like, ‘I’m doing something that’s about secrets or secret sources or networks of information. Let’s show All the President’s Men.’”

“Once or twice a year at the Walker,” he adds, “a film will show up and my colleagues will be like, ‘Why are you showing that?’”

Digital projection became the dominant format for new releases around 10 years ago, and today the little black circles in the corner that cued the projectionist to change reels are almost all gone.

And with them, Moret says, went “the immediacy of the moment.” He points to a recent Trylon screening of Punch-Drunk Love, where he mis-framed one of the reels: “I don’t want to do that, but there’s an element that reminds you that someone is working hard on it.”

Unlike the computer files that contain digital movies, a film reel gets closer to its final run with each viewing. Moreover, Moret points out, each film print ages differently, so each becomes its own version of the movie. “There’s something very of this moment and temporary about it,” he says, making each screening all the more special.

Film shows its age with scratches and slight discolorations (who among us?) but with film, Moret says, “There’s a density to the image that’s really different. It feels deeper. It feels like the colors are more thoroughly separate, it feels like the blacks are more black.”

“Anything black and white, in general,” Letness agrees, “is going to look better on film.”

Schilling is pretty confident that the Heights is the only place in the country that shows a particular Technicolor print of The Wizard of Oz each year.

“It was so overwhelming,” he recalls of first seeing this copy, “I would describe it as looking at a van Gogh in a coffee table book and looking at one in a museum up close. Colors are just coming at you, and they are just so rich, it looks like it’s a hand-painted film. It’s just gorgeous.”

During the original 2021 release of Licorice Pizza the Heights showed it digitally, but they recently showed it on 70 mm film. Letness didn’t notice any lack of quality with the digital version, but on the re-screening found the “70 print has way more punch to it.”

Alas, not everything can be shown on film. Wear and tear and changes in the film business mean there just aren’t as many film prints available as there once were.

Schilling mentions that for the Jack Lemmon series at the Heights this summer, they can’t show the actor’s Oscar-winning movie, Save The Tiger, because there are just no prints to be found. “I swear this happens every year,” he says.

Even prints that do exist aren’t always easy to find. In plenty of cases, the distributor is gone, and their catalog was parceled out to other companies, or the distributor still exists, but the rights have reverted to a different company. Then programmers need to follow unmarked trails to find them. “Sometimes,” Moret says of studios that take in new rights, “they don’t even know what they have, and I have to prod numerous different people to look.”

It can be even more complicated. In May, the Trylon is showing Elaine May’s The Heartbreak Kid. “The whole time I’ve been programming I’ve wanted to show that movie,” Moret says.

But, like many films in the 1970s, when tax shelters and money laundering were factors in how movies were financed, The Heartbreak Kid is rumored to have partly financed by the mob. “Once stuff with John Gotti and all that happened, they lost their part of the rights and it went completely to Bristol Myers Squibb,” Moret says.

“They own the rights to this movie and like seven other movies,” Moret explains. “And they have no ability to take care of materials, they have nobody who can book the films because they don’t have a film booker, they have random lawyers who don’t understand how this works, so these movies have basically been unavailable to watch for decades.”

Moret finally was able to track down a film collector in Texas who owned a 16 mm print of the movie. The Texan negotiated with Bristol Myers Squibb, and they are now letting him show a fresh scan of that print.

The number one limitation, though, is cost. Letness explains that shipping alone can sometimes cost hundreds of dollars for one movie, and for the larger format of 70 mm, the costs can run past $1,000. That’s one reason that less than half of what these theaters show is on film.

That’s unfortunate. But the times these theaters do get to bring people together around a great movie on a great print, it's worth it.