In May 2023, HUGE Improv Theater made a big announcement. After 13 years at 3037 Lyndale Ave., the theater was relocating to a new, larger space a few blocks away. The move would mean roughly 3,000 additional feet of space, and, for the first time, the pioneering improv company would own its building.

But by October of the following year, HUGE had closed, citing insurmountable financial challenges. And that was that. The Twin Cities lost the only venue in town entirely dedicated to longform improvisation.

The closure of HUGE has been a blow to the local improv community—of course it has. But, as we learned in conversations with a dozen area improvisers, it’s also presented an opportunity. Over the last six HUGE-less months, the scene has seen an infusion of energy. New groups are staging new shows and taking over new venues, and improv is coming to places that would have been unthinkable just a year ago.

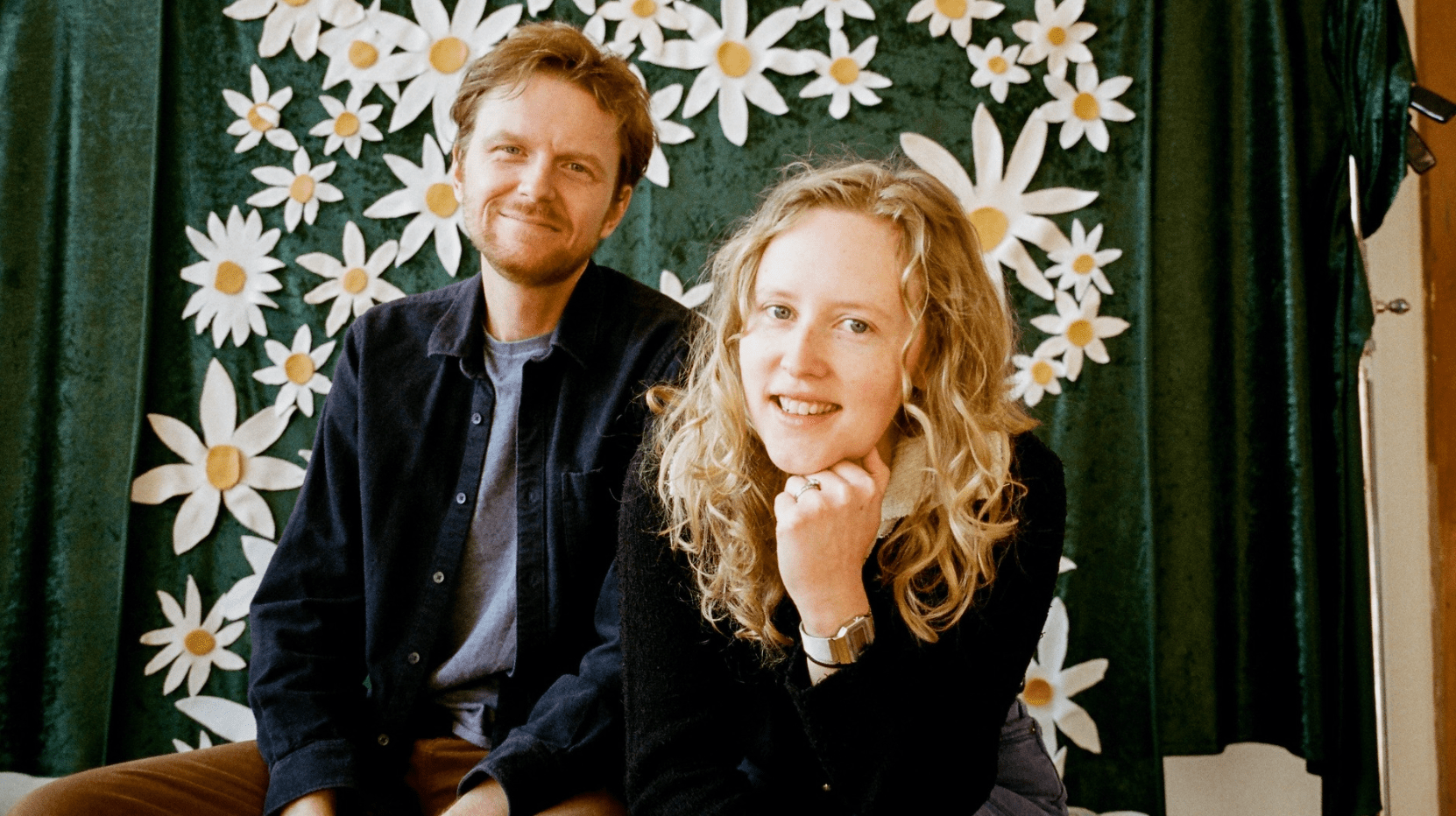

“It’s a community of improvisers—we work best making it work even though it shouldn’t,” says Philip Simondet, who’s producing a new Bryant Lake Bowl improv series with his wife, Sarah Arnold-Simondet. “There is kind of an energy of, well, we have to make creative choices, because we don’t have what we had before. We have to come up with something new.”

A HUGE Undertaking

In 2005, around the time of the national improv boom that saw The Upright Citizens Brigade expanding from Chicago to both coasts and The Second City becoming a household name, HUGE was founded by a group of local improvisers: Jill Bernard, Butch Roy, Nels Lennes, Joe Bozic, and Mike Fotis.

“Like every improv theater in the entire world, we started as a group of friends who just wanted to make stuff up on stage. That’s it! Nothing noble,” Bernard tells Racket. “Sometimes people retcon that we were so forward-thinking, but we just wanted to make stuff up with our friends, like every improv theater.”

At the time, there wasn’t really a designated longform improv theater in the Twin Cities. (Yes, Brave New Workshop had been around since the ’50s, but it also emphasized sketch comedy and satire. Semantics!) Instead, groups produced shows independently all over town, but there were plenty of challenges associated with that; improvisers often found themselves relegated to off nights at traditional theaters, or performing on someone else’s set. Finding space to practice or rehearse was an eternal struggle.

“We were looking around, and it just seemed like there was enough improv to have a theater for it, to have a designated theater,” Bernard says. “The goal was to have a place where you could just walk down the street and know there was gonna be an improv show that night.”

HUGE (an acronym for Hey U Get Entertainment) opened the doors to its original Lyn-Lake space in 2010. Bernard says audiences were interested and invested right away—even if, she admits today, six nights of improv a week might have been an ambitious opening goal.

Among HUGE’s hallmarks was the fact that it welcomed performers at any stage in their career. Just learning about improv? There were classes and jams where you could try it out. If you were early in your career and wanted to try something experimental, there was Improv A Go Go on Sundays. HUGE Wednesdays were for groups that were ready to have their own show but needed a “beta test” environment, and there were weekend slots for more established groups producing their own thing. “As well as, we were auditioning shows all the time, so that an individual artist could find their way into a cast,” Bernard explains.

The benefits were numerous, from practical concerns of practice and performance space to less tangible advantages of fostering friendship and community. HUGE was a place where you could go and find like-minded artists—roughly 200 of them—and just about every area improviser’s path took them through the theater at some point, whether they eventually landed at Stevie Ray’s Comedy Cabaret in Chanhassen or ComedySportz or Brave New Workshop in Minneapolis.

“I fell in love with the concept, first off, with HUGE, which is, it is a place where people actually have a stake in it,” says John Gebretatose, co-founder of the all-Black Minneapolis improv group Blackout. “People owned it.”

“They were able to capture the sense of community, I think, in a way that is kind of rare and hard to do,” adds HUGE co-founder Fotis, who left to explore other projects before the theater opened. “It was impressive to see how many people took personally the wellbeing of a physical space. And I think that’s a credit to the type of environment that everyone tried to create over there.”

Nearly everyone we spoke to for this story mentioned the environment at HUGE, which felt different—more warm, welcoming, and diverse—from what you’d find in other improv scenes around the country. Gebretatose became HUGE’s co-executive and diversity and inclusion director in 2016 and introduced jams and workshops for performers of color. When the #MeToo movement sprang up, HUGE took it as an opportunity to reinvestigate whether women, nonbinary, and queer participants felt welcome.

“One of the biggest differences I saw when I moved here was the whole idea of boundaries,” says Steph Callaghan, a former HUGE instructor whose improv career started in Chicago. She remembers being invited to take part in HUGE’s BIPOC jam shortly after moving back to Minneapolis and the surprise she felt at just how many different jams there were: a 40+ jam, an “average joes” jam for people with disabilities, a queer jam. (Jams are more casual gatherings where improvisers create scenes together—like an open mic, for improv.)

“In Chicago, it’s a very white, male-dominated sport,” she says. “And if you’re a woman, or a person of color, or if you have different abilities, it’s very difficult to break into the scene. It’s very hard to prove yourself.”

Bernard says HUGE was greatly invested in making sure its classes were safe. The theater had a bill of rights posted on the wall and sent documents to performers so they knew what conduct was expected of them and what was out of bounds. There was a way to report people who were predatory or who were creating bad situations in classes, shows, or rehearsals. “People would even report things to us that had happened at other theaters; we were a central hub in that way,” Bernard says. “I do worry that [since HUGE’s closure] there’s not as many safeguards to protect people.”

Those values do live on in the thousands of improvisers who came up through HUGE over the years. Callaghan has since gone on to found Minneapolis-based Very Good Improv with Laura Berger and Chris Rodriguez, whom she met while teaching at HUGE in 2024, and the trio all say they prioritize making their classes and workshops feel as safe and as inclusive as possible.

“I don’t see it as a failure—I still see that we won,” Gebratatose says. “We walked in, we told everybody, ‘We’re not gonna have a script, this is not no Cirque du Soleil,’ … It’s a bunch of regular folk, like you and me, coming in with a hobby they just learned like a year ago. And you’re gonna pay a ticket price like you would to see a Marvel movie or something to watch them do it.”

“I’ve been using this metaphor to describe it: I was always imagining passing the torch, I just didn’t know that we would like, clumsily drop the torch in a dumpster and set it on fire as we tried to pass it,” Bernard says. “But I knew the torch would be passed to a new generation.”

Yes, and… Now What?

On Friday nights at Bryant Lake Bowl and Theater, two different improv groups—new ones each month—take the stage, performing for 25 minutes apiece. The show is a tight one hour, but the fun doesn’t stop after everyone clambers off the stage. Instead, the cast and the entire audience are encouraged to migrate over to BLB’s restaurant and bar side to hang out, get drinks, goof off, and “do bits.”

This is The Residency at BLB, a new series started by the husband-and-wife duo of Philip Simondet and Sarah Arnold-Simondet in January.

“A big thing that happened when HUGE closed was everyone was kind of mourning that social aspect—the ability to gather after shows and chat in the lobby and just be around friends,” Arnold-Simondet says. The Residency is intended to build that back, giving local improv performers and enthusiasts a reliable place to gather in person, week after week, and close down the bar if they so choose.

“We started The Residency because we were like, we want to make sure improv keeps going in this city, and because we love improv, and we love our community, and we just want to make sure that it doesn’t die out because HUGE died out,” Arnold-Simondet continues. “I think a lot of people felt that way after HUGE, like, ‘Well, I’m going to take up this mantle and make sure that improv continues in Minneapolis and St. Paul.’”

The pair say this is an exciting time, if an uncertain one, with new groups forming and new shows popping up at venues all across the Twin Cities. And most performers expressed a version of this sentiment—that while losing HUGE was a blow, the loss has invigorated the improv community, opening performers up to new venues and leading to the formation of new groups, new shows, new jams. In some ways, it’s even been a long time coming.

“For years, HUGE had been trying to push people out of the nest in a way, saying, ‘Hey, go out, teach your own classes, find places to do shows,’” says Sean Dillon, HUGE’s longtime managing director.

“When you do have a central space, people rely on that space for their opportunities,” adds Very Good Improv’s Laura Berger. “Improv comes from people who are motivated, who want to hustle, who want to be weird with their friends. And if you’re just waiting around to get cast in a show at the one theater you think improv happens at, you’re not going to go be weird with people.”

So, local performers have been hustling. Gebratotose founded Good Camel Comedy Theater, which in addition to classes like Improv Decolonized hosts the monthly Oasis Laugh-Battle at LUSH Lounge & Theater in northeast Minneapolis. In the Laugh-Battle, one cast member gets to invite a family member or a friend or a coworker—someone in their life who doesn’t do comedy or improv—to compete in the show.

Sean Dillon’s long-running HUGE show Off Book, which he co-directs with Isabella Dunsieth, pairs an actor who’s memorized a script with an improviser who very much hasn’t, and it now appears in south Minneapolis at the Jungle Theater once a month as part of its Improv at the Jungle series.

“The real irony is, we’re now reaching sort of a more classic theater audience that we had a hard time reaching when we were at HUGE,” Dillon says, Off Book’s Jungle performances have earned rave reviews from local theater websites Cherry and Spoon and Stages of MN, which called Off Book “hands down… the best improv show I’ve ever seen.”

“I think a certain amount of the public just sort of wrote off improv as, ‘Oh, they do funny Whose Line is it Anyway? type of stuff,’” Dillon says. “Not that I blame anybody for that, but there is some frustration in: Why did we have to close down the improv theater to get people to come see improv?”

Very Good Improv calls Uptown’s Phoenix Theater home, and Mike Fotis says Strike! Theater in Northeast, where he’s also a co-founder, is looking for ways to support less-experienced performers in addition to its existing improv programming: “You’ve got to get up on your feet in front of people.”

“It kind of reminds me of before HUGE started, where people were really trying to get shows up all over the place,” Fotis says. “I’m glad that people are trying to take it as an opportunity to move forward and try shows and try other venues and things like that.”

The co-founders of Very Good Improv describe the Twin Cities’ improv scene as “special,” “unique,” “very experimental,” and “very weird.” There’s a real love for genre and narrative improv here, and The Twin Cities Improv Festival, which takes place June 5-8 this year, is known as a place for out-of-town performers to try their stranger and more outlandish stuff. Their hope is that, outside of HUGE, theaters will continue to welcome that kind of bizarre and unusual longform improv.

Of course, Arnold-Simondet says, it would be great to have multiple improv theaters in town; in an ideal scenario, she says, “There’d be so much improv you’d be nauseated by it.” And it can be difficult to reach people with news about new shows, especially as folks move away from social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram.

“I’m certain there’s less total improv happening now than there was when HUGE was around, just because [there were] 10 to 12 shows a week at that venue,” Dillon says. But among the advantages to seeing improv all over town, at arts spaces like 825 Arts in St. Paul and legion halls like the Eagles 34? “It makes us harder to avoid,” Dillon chuckles.

But for all the brave faces and chins held high, the closure of HUGE does raise concerns.

“The loss of HUGE is huge, I don’t think that’s something that should be understated. The loss of the space is a big one,” says Destiny Davison, a member of Blackout and co-host of the new improv variety show The Honey Jar. HUGE was the longtime home of Blackout’s Black and Funny Improv Festival along with other fests like the Queer and Funny Improv Festival, which landed at Minneapolis’s Red Eye Theater last November. “The loss of the space has come with unknowns,” Davison says. “Where do we go from here? How do we best be of use to our community? How do we actively produce while also taking time to reflect on what we’re making?”

Many spoke to a feeling that the community is “scattered” or “disconnected” since HUGE’s closure, or mentioned the loss of an important third space.

“After a show was done, people could hang out, and really the only time limit that was enforced was what time the people in front of house wanted to go home,” says Evelyn Vocu, an improviser who’s also a prolific photographer of the community.

“We go from seeing each other every single week, or multiple times a week, to—some people I haven’t seen since, you know? That, to me, was the hardest part, was that our community became so spread out,” says Chris Rodriguez, one of Very Good Improv’s three co-founders.

And while other local theaters have welcomed improv groups onto their stages over the last six months, it’s not quite the same as having a central improv hub. There’s also no guarantee those stages will stay open to improv forever. “I guess the best way I can describe it is it feels like there’s more shelters than there are homes for the improv community,” Vocu says.

Six months out from HUGE’s closure, there’s a lot of energy and excitement as improvisers embrace this new frontier. But will that momentum carry through a year from now? Five years from now? “It’s a lot of work to start a show, but it’s way more hard work to keep a show going,” says Simondet of The Residency at BLB.

Other performers worry about the longterm implications of not having a designated improv theater in town. Will improv newbies know where to look if they’re curious about the art form? Will they be encouraged to grow without the many levels of instruction HUGE offered and the varied types of shows it staged?

“It’s kind of like, have you ever seen a population density chart of when people stop having children?” asks improviser Angelique Lisboa, who performs with shows including Whose Beer Is It Anyway? and Family Dinner. “The people who have had their comedy children are going to grow up and out and retire. And so the closing of HUGE is kind of a hit, in my opinion, to new comedy children—although those children are very well, like, 32-year-old IT professionals.”

But even though Lisboa is a relative newcomer to improv—she’s been performing since 2020—she feels more optimistic than concerned about the HUGE-less future.

“I personally think it’s kind of good, as weird and loaded as those words sound,” she says. “It’s a very punk-rock time for those people who are newer to their own little comedy journey.”

And, Scene?

A few months ago, HUGE’s Jill Bernard launched the website Twin Cities Improv, a calendar collecting all of the disparate improv shows happening throughout the Twin Cities. “I registered that domain 10 years ago,” she laughs. “I’ve been thinking about this website for 10 years, and finally the need was there.”

In a gratifying moment, the calendar filled up right away. Clicking through it, you’ll find many nights are full of four or more shows, both longstanding ones (like Soda Pop Improv and Improvocation) and newer ones (The Honey Jar, Improv Zodiac!).

“There was something about collecting it all together and seeing the scope of it that just felt good,” Bernard says. She recalls studying theater at the U of M in the early ’90s and having this idea of improv as a respected art form on par with scripted theater in the Twin Cities.

“I distinctly remember having a dream that you’d be able to see improv on stage at the Jungle,” she continues. “And to have that come true the minute after we closed… it just felt really like some kind of completion of a journey.”

“In a way, I think it’s healthy for us to have our sort of ‘wandering in the desert’ moment here,” Dillon says, adding that, when he started performing improv in New York, a lot of his experience was in the back rooms of bars. “That was kind of a right of passage, playing to crowds that are only half paying attention, competing with noise from the front room. And I think there’s some value in getting those reps in.”

(Though he adds: “I think in the long run, man, it would be great if there were at least one physical space here in the cities that was just dedicated to improv.”)

Davison puts it matter of factly: Things change, and spaces come and go. “No matter how we might feel like our communities are static, they’re really not,” she says. “They’re changing all the time.”

“I think it gets people out of their comfort zone,” Lisboa adds. “Which, ya know, is kind of the whole thing of improv.”