Welcome to the latest installment of Let's Taco 'Bout Politics, a series that has us sitting down with as many 2025 Minneapolis mayoral candidates as possible over Mexican food. During the coming weeks, joined by Wedge LIVE! correspondent Jason Garcia, we’ll be getting tacos, burritos, quesadillas, and tortas with as many mayoral candidates as possible. In the hot seat this week…

Name: Jazz Hampton

Current Position: Co-founder, CEO, and general counsel of TurnSignl

Background: Hampton is a lifelong Minnesotan; he grew up in Richfield, the youngest of four, and today lives in southwest Minneapolis with his wife and three kids. A lawyer, Hampton has served as a public defender, and he worked with the Great North Innocence Project to help exonerate Marvin Haynes. After George Floyd’s murder, he co-founded TurnSignl, an app that connects drivers with attorneys during traffic stops. He also teaches entrepreneurial finance at the University of St. Thomas.

What’d he order?: Two barbacoa tacos ($6 each) from Nico’s Tacos & Agave Bar on 50th Street & Penn Avenue.

Em Cassel: Tell us a little bit about why you want to run for mayor.

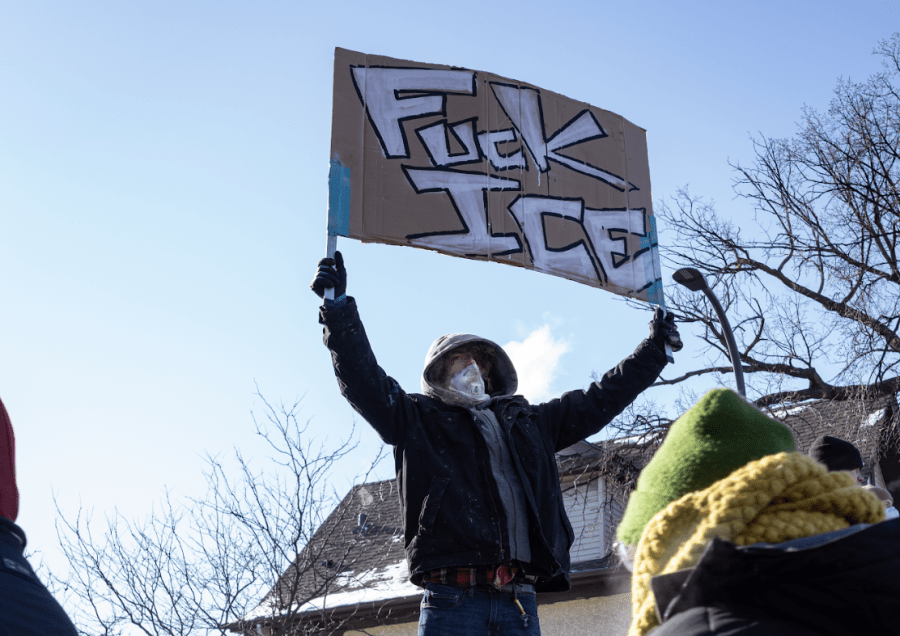

Jazz Hampton: I’ve spent my career seeing problems and trying to address them in whatever way possible. The most recent version of that is my current job, which is I’m the CEO of TurnSignl, an app that connects drivers to an attorney in real time when they’ve been pulled over to protect their rights, de-escalate interactions, and get them home safe. I was a former public defender that was working in corporate law, and after the murder of George Floyd, I just kind of looked in the mirror and was like, “What am I doing, using my law degree as a Black lawyer in the city of Minneapolis, to be a part of the solution?” I had gone to all the marches and the protests—I was on 35W with my wife when that semi rolled through—I had been to all the things, but have I taken the next step to take the baton? Because I firmly believe protests are the start, and then the baton can be handed off to the next group that’s doing the work.

So I quit corporate law to start TurnSignl four years ago with Andre [Creighton] and Myke [Frelix], and I remember, as a lawyer, I thought I’d be a litigator for the rest of my life. I’d never leave the corporate realm. Until I felt the need and the pull to be somewhere else with TurnSignl. And that’s the same feeling that I had with running for mayor. I saw the lack of traction that we have seen over the last several years; I saw the tension between groups in city leadership. And frankly, I’ve lived on both sides of the track for so long that I really felt I could sit at the table and say, “How can we actually get something done and make some progress?” Most importantly, with wild optimism and positivity and happiness. From college football to being a lawyer, I’m tough when you need to be tough, and I’m leading an organization now. But I want someone to vote for me because they are super excited to vote for me, not because they’re voting against someone else.

Em Cassel: You want them to be literally jazzed about it.

Jason Garcia: That is kind of a thing we saw in the last election, where it felt more like people were running against someone and against the status quo versus saying, “Here’s why you should be excited to vote for me.” What do you think is something, specifically, that will get voters really excited to vote for you?

Hampton: I think it’s that not only do I see an issue like TurnSignl and try to do things—my background is much more diverse than just that—but if you talk to any candidate about the issues, I feel like a lot of them are going to say three of the same things in some order: affordable housing, public safety, ensuring that small businesses are doing well while workers are treated well. That’s what I say, and I’m sure all of them would say something similar. But what I think is true for a lot of people in this city is, they’re worried if they choose someone who’s been leading for a while already, that they aren’t going to get that change and progress that they want. And so one is, coming in as an outsider, from outside of the establishment.

I get a lot of people saying, “Oh, are you nervous because you haven’t held city or elected office positions before?” And I say “No.” I’m a cofounder and I run a business. I teach entrepreneurial finance; I know what a PnL [profit and loss statement] looks like. I teach it on the university level. I’ve been on the Catholic Charities board for four and a half years because I care deeply about our affordable housing needs. I’ve been on the Great North Innocence Project board, and I represented someone who was wrongfully incarcerated successfully, to free him after being incarcerated for 19 years. I’ve been doing the work, and now I have the opportunity—just like I felt in terms of being a Black lawyer with a computer science undergrad degree—I felt the same call, like now I can step into this space and be a part of the movement, momentum to get things done, and bring everyone to the table.

Cassel: I am curious about TurnSignl, in general. It’s been four, four and a half years—how have things gone for the business during that time? It’s a little bit separate from the mayoral conversation, but I’m wondering: Are people using it? What is that looking like?

Hampton: As I walked in here, we received a message from someone saying, “Hey, I’m working on downloading my video right now, I just used the platform.” It’s used over 150 times a month, on average, and we’re right at, if not just over, 200,000 on the platform right now, in every state in the United States. When you press the button, you’re connected to a lawyer, in real time, on a video call, that practices law in that jurisdiction. What is legal in Arkansas is different than Arizona, so they know the laws of that area and can guide you through it and can follow up after. The important thing I always need to say about TurnSignl is also, if you’re a person who’s raised their hand to say, “Hey, this is something I don’t feel like I’m comfortable or able to pay for right now,” we give subsidized memberships to those individuals through partnerships with people like Blue Cross Blue Shield Minnesota, who identified racism as a public health crisis, all the way to the Minnesota Vikings. We have over 20,000 people who have never paid for the platform.

It’s used all the time. And my face lights up when I talk about this. When you’re working on a business and there’s that many people, it feels like you’re focusing on a very high level. But the testimonials that come through: a teenager that’s pulled over by an unmarked police car late at night. She’s like, “I don’t even know if this is a police officer.” So many stories. And by the end of that interaction, he was like, “Hey, you actually handled this interaction really well.” I know it can be really scary. She didn’t get a ticket—that’s not what we guarantee or promise, but cool—but to get, even a compliment from the police officer. We always say we’re an app to bridge the gap, we’re not an adversarial platform. We’re here to help people understand their rights.

Garcia: One of the things that we were just talking about before we started recording was the water main break here, just across the street, and how that’s impacted some local businesses and how there’s been maybe not the best feeling between business owners and the city. If you’re elected, how do you see yourself handling a situation like that, where there’s not an immediate person or thing to point at and say, “This is at fault”? How would you go about trying to work with and repair that?

Hampton: It’s funny, the word “repair” is an important part of this, because of course the fix has to be implemented as soon as possible, with what occurred. But also, part of this leans into a lot of the infrastructure work that gets done. No one likes when their road gets torn up, but no one likes when something that’s under their road causes damage. It’s a fine line to balance, and everyone is super upset. It actually reminds me a lot of TurnSignl—when we’re successful, nothing bad happened. And it’s really hard to prove that something didn’t happen. So not only do I feel like the city has to be very active in that work, saying, “This is what we’re doing and why,” if anyone thinks about all the construction that they interact with in the city of Minneapolis, I would love for them to say, “Oh, this is making my journey a little longer, but I know that they’re doing X, Y, and Z to help the city’s infrastructure so things like that don’t happen.”

If something does happen, and it is the city’s fault, I want us to address that and handle it in an expedient way. And financially, when we have $75 million in police misconduct payouts since 2017—I’m glad that folks are being compensated, and they should be when things go wrong—but also, let’s make sure that doesn’t happen. Whether we’re talking about police interactions or we’re talking about water mains, it’s a lot cheaper to handle it on the front end. And we need to try to keep that in mind.

Cassel: I’m very curious what will happen, and what your thoughts are, about the relationship between the mayor’s office, the police department, and the people of Minneapolis. It seems like—we talked about this during our conversation with Omar Fateh—right now, it’s a situation where nobody is happy. People who want more police are unhappy; people who want less police are unhappy. There’s a lot of discord on all sides. Do you have ideas for how you would begin to resolve that very contentious situation?

Hampton: This is honestly one of the things I want to lean into most as mayor. Back to “I’ve lived on both sides of the track”: My car has been stolen from in front of my house multiple times since we moved here a few years back. It’s rummaged through even more. I was standing outside watering my lawn at noon, and the car right behind me, my neighbor’s car, was burglarized. I chased the car—like it took off, and I chased it to the other side of the school, where another car was being burglarized. We’re calling [the police], communicating, and we don’t feel like it was addressed. In that last one, the officer never came. The police never came. We need that to be better. In the past, my wife was out of town and I was home alone when the security alarm went off, and they call and ask for your code or whatever; I didn’t remember the password, and they were like, “We’re going to dispatch the police.” And I called my wife, who was in California, and explained what happened, and I said, “I’m going to run down and hide in the basement because I don’t want the police to see me in our home, and I’m too scared to run out the front door because they might see me doing that.” I’m just scared in this moment after calling 911.

Both of those things can be true and are true. I’ve experienced both as a Black man in the city. I can sit honestly and understand that both of those things are true, and we need to build a solution around it. We need to have a robust public safety system that is more than just individuals with guns. We need to also ensure that fire departments—I talked to a fire fighter recently who said, “We’ll go to calls, and people will yell at us because we don’t go into the building to help, but we can’t go in until it’s cleared by the police on some calls, and they aren’t there yet.” They need someone showing up in a timely manner. So what’s the base-level solution? It’s trust. It’s building trust back so that citizens feel safe… but also, trust coming back the other way. If officers don’t like what we’re doing, I don’t care how much people are trying to pay them, they won’t come here. They’ll work in another city.

Garcia: One of the other things we tangentially touched on while we were just chatting before was: It’s a beautiful day out, a great day to bike and walk around the neighborhood. Right now, one of the big transit projects that’s coming through this part of the city as well as going through downtown is the new Bus Rapid Transit Line. There’s also talk about taking the buses off Nicollet Mall, moving them to Hennepin Avenue, and things like that. As somebody who lives in the southwest part of the city, what is your interaction with public transit and how do you see that as part of the city of Minneapolis?

Hampton: I view it as a vital part of the city of Minneapolis. There’s so many folks who work in places across the city who might not live in close proximity and can’t spend all their money paying for Ubers or other things to get to that location. So I think it’s vitally important. I believe firmly that we have to keep expanding that infrastructure to be helpful to individuals who rely on or prefer public transit. What’s also important about that, because I think all these things connect: I talked to a woman who runs programming at North Minneapolis High School, and she said she has young women that would rather pay $18 for an Uber to get somewhere than ride on public transit because they don’t feel completely safe. That is tied in—the next one, which might be another conversation, is affordable housing, which also connects to policing, and affordable housing connects to public transit. We need to have an infrastructure that is robust and supportive of individuals that prefer to or need to take public transit, and ensure that we’re doing everything possible to do it in a way that isn’t disrupting people, businesses, etc.

The mayor, in a strong mayor system, has an opportunity, duty, responsibility to appoint individuals into those leadership positions within the city that aren’t just ideologically close with them or have personal relationships with them—it’s people who are the best people for that job. Minneapolis has too often been thought of as the younger brother in all of the 50 big cities. We need to be the city where someone’s like, if you have that leadership role in transit in Minneapolis, you’re on deck to be a part of the national leadership.

Cassel: You mentioned the strong mayor system, and we’ve done a lot of talking about that in these conversations. Do you have any thoughts about, I guess, the big component of that, is having a relationship between the mayor’s office and the city council and what that would look like. I don’t think it’s a secret to anyone at this point that the relationship between the mayor’s office and the city council is quite strained, so how would you work with the city council? Are there things you would do differently? Things you would introduce?

Garcia: And to quickly throw another part of that in, are there people on city council right now that you feel like you have a good connection with and that you’d be comfortable working with right away?

Hampton: Yeah, I’ve made a point to reach out to city council members—I was just talking to one yesterday—everyone from the City Council member that represents me [Linea Palmisano] all the way through the current vice president of the city council [Aisha Chughtai] to say, “Hey, here’s what I’m thinking.” I’ll use an analogy of my business. TurnSignl, we had three co-founders and leaders of the business. And we agreed that we’d make decisions by a majority vote. One rule that we put in day one is, if any one of us feels like something is going terribly wrong or you disagree, you have one veto per year that you can use. In those four and a half years, not one of us ever used that, and I’ll tell you why. The closest we ever got was one of our co-founders said, “Hey, I do not agree with this decision, I do not think it’s the right personnel decision, and I just want you guys to know, after arguing for two and a half hours, that I’m considering using my veto.” And you know what that did? We extended that meeting for another two hours, and we got to the bottom of why he felt that way. If he felt that strongly, I believed that we had to continue that conversation. And by the end of it, we agreed to go with his path without him using the veto. Two months later he changed his mind, and that’s fine.

What’s the point of that story? The veto should be something that helps you understand how serious the matter is and gets you to the table to finish the work and finish the conversation. I don’t feel like we need to be using the veto as much as we have been the last two years; I think we need to be at the table. I believe this, and I would encourage anyone to ask the city council or the mayor—I don’t think they’re at the table. And I’ve heard that firsthand. I think we need to be at the table having that conversation, even when it gets hard. Being a mayor means that you are leading the conversation but also hearing what everyone is saying. And we need to get back to that.

Garcia: You mentioned that you played college football…

Hampton: Well, I was on the team—I was on the bench.

Garcia: You went to practice every day! I was fortunate enough to be involved in athletics when I was in college as well, and it helped sharpen my concept of what leadership looks like and what teamwork looks like, things like that. As somebody who has a strong background in working as part of a team to achieve goals, you mentioned you haven’t held elected office before, do you have a team around you? Who do you go to to ask questions about, “Hey, I’ve never done this before, what do I need to know?”

Hampton: That’s one of the opportunities that I have is to take my experience from being outside of elected office and pair it with folks who have experienced elected office, who have worked in public service for many years, and help understand how I can bring my viewpoint, my diversity of thought, into this conversation, but understanding the mechanisms, and the organization, and the structure in which to do it. My campaign manager was one of the first people that I felt really strongly about—she is a current employee within the city, she’s doing really great work there. And I think that she has had an incredible influence in what has happened in the city, and I’m excited that she’s brought that to our campaign already. Beyond that, I’ve reached out to and been working with folks who’ve had experience in local politics all over the Twin Cities: mayors of other cities, city council members from other cities, and also, of course, ours.

When I co-founded TurnSignl with my co-founders, I knew nothing about starting a business. I took one entrepreneurship class in college. Four and a half years later, I’m teaching entrepreneurial finance at St. Thomas. I had an accelerated path to understanding a new system, which is something I’m able to do and excited to do, and this feels very similar to that.

Cassel: We’re at Nico’s, it’s wonderful—do you want to talk a little bit about this restaurant, or any of the other restaurants you frequent in this neighborhood? What are some of the other small businesses and restaurants that you like around here?

Hampton: I grew up as the child of a restaurant owner, my mom owned a restaurant called King Oscar’s that was on 66th, just across town in Richfield, right by the Richfield pool. I grew up in the restaurant industry—I have pictures of me cutting potatoes when I was far too young to be doing it, sitting on top of a table at the restaurant. Unfortunately, my mom had to shut the restaurant down when I was in about sixth grade, and from there we all just migrated to Applebee’s. The entire crew went and worked at Applebee’s together, and I worked there for years and years. So I just have a deep love for it, and we still go out to eat more than we should.

Broder’s is across the way, it is unbelievable—that’s a special-occasion spot for sure, and what people don’t know is the DoorDash pizza options are super affordable from the little walk-up place they have across the way. Our office is in northeast Minneapolis, so we hit up Stanley’s a lot; 1029 is my go-to spot for wings and lunch. I love Maison Margeaux, their smoked old fashioned is really, really great. And then I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Stepchld and Parcelle. I went to college with [owner] Kamal [Ansari]. And if I can sing karaoke at 1029, I’m there.

Garcia: So that’s usually the question that Em asks, and then I follow up by saying—and maybe we’ll get a really good answer from you, since you grew up cooking and in restaurants—what’s something that you like to make at home? What’s your specialty, or something you really enjoy making when you’re at home?

Hampton: I really enjoy making breakfast foods, because I don’t need much sleep to operate. I stay up late and I get up early, especially with our three kids that are 7, 5, and 3. The reason I like it, also, might touch back to: My early mornings growing up, I would go to my mom’s restaurant before school, so it was all breakfast food at the time. There was a guy named John Cardinal who was a cook, and he always said, “I’m going to make the perfect omelette, and the day that I make it I’m quitting, I’m done, I’m retiring.” And every day I would walk in and say, “John, did you make the perfect omelette yet?” And he’d say, “I’m still standing here, aren’t I?” So I love making omelettes, and that’s probably why, now that I think about it. You can throw anything in there and trick the kids into eating it—spinach or whatever. I know it’s an interview, but what about you all?

Cassel: My favorite thing to make, which is also incredibly messy, is I like to make karaage. It’s just one of my favorite snacks and foods, and it’s just easy enough to make at home where you’re like, “Yeah, this is reasonable,” and then you’re dropping things in hot oil and it’s a chaotic mess. So I do it every couple of months after I’ve forgotten just how difficult and messy it will be.

Garcia: I really lean toward comfort foods; my grandmother on my mom’s side also owned a restaurant, and when I was young she worked as a cook in a restaurant. My grandmother on my dad’s side, she never learned to speak English, and when I was young—and still now—I spoke very little Spanish. So a lot of our connection came from me watching her cook and her pointing at things and showing me how to do things. The things that I really enjoy making are comfort food things: tacos and enchiladas and things like that. That’s the Mexican side of the family. When I’m feeling more like I want to dig into the stuff that my grandmother would make, it’s a lot of pot roasts, or like—I’m not in practice with making biscuits anymore, but biscuits and gravy. Biscuits and chocolate gravy was something my grandmother would make. It’s kind of an Arkansas thing, but it’s basically something that came out of being really poor and trying to stretch out ingredients. It’s kind of like a thin chocolate pudding that you eat with hot, buttered biscuits.

Hampton: I’m a big, big rap music fan, and that reminds me of a lyric from a rapper from Chicago who said, “They gave us scraps, some of it old/We cooked them up and called it soul.” I love that. My dad’s Black and my mom’s white, and so at my mom’s restaurant, they served lutefisk, which is gelatinous, gross, and then my dad, when they were having family events, they’d cook chitlins. I really had all portions of this.

Garcia: One question, kind of to tie it into what we just talked about, is that one of the priorities you talked about is small businesses thriving in Minneapolis. Is there anything, where you look at the situation in Minneapolis right now, that you would want to tell voters—these are the things that I would do, when elected, to help you out? Especially our immigrant-owned businesses, our minority-owned businesses?

Hampton: As three Black men that started our business, we’ve seen what it’s like, and I have happy hours and lunches with Black business owners weekly, because we see firsthand what it’s like to be in that space. So from an experience standpoint, I already know where a lot of those things are coming from. Speaking more generally about small business, what I hear time and time again from folks is, there’s this nebulous phrase that everyone uses: “There’s just so much red tape.” But I always like push that one step further and say, “Help me understand what you mean by ‘red tape.’” What I’m hearing from folks is, “When I’m reaching out and I’m waiting for a permit, I don’t know who to call.” Or “I don’t get answers back for days or weeks on end.” Or “I have enough money, as I’m building out a restaurant like this one, to build it out over the course of two months, and anything past that, you’re jeopardizing the success of the business.”

With permits or waiting to hear calls back or waiting for an inspector to come out, when that stretches too far, then the business is in trouble. It’s some of those things that I really want to address right away with small business owners. The other thing, and I say this a lot, is there’s a phrase—all those things can be a rising tide that will raise all boats. What I feel like people don’t appreciate or don’t understand is, some peoples’ boats have holes in them, inherently. So we also need to plug those holes while we’re raising the tide. Or else, those boats are just going to continue to flounder and eventually sink. So I think it’s a yes-and. Of course we need to do everything to support all small businesses, but we need to look at why there are holes, and what they are, and fill them, especially for minority-owned businesses and for other businesses that are struggling to thrive because of other systematic or city-related issues.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Previously in Let’s Taco ‘Bout Politics, we sat down with Minneapolis City Council Member Emily Koski, Reverend Dr. DeWayne Davis, and DFL State Senator Omar Fateh. Check back for conversations with the rest of this year’s mayoral candidates.