“WHAT DO YOU IDENTIFY AS?” A grainy, swaying head welcomes me and demands a choice. Three large buttons are arranged on a console before me:

1) I IDENTIFY AS BLACK AND TRANS

2) I IDENTIFY AS TRANS

3) I IDENTIFY AS CIS

I bristle. The options feel limited, and I do not like being boxed in, neatly defined. Nevertheless. I pick the third. I am identified as a potential threat.

“YOU HAVE BEEN RESPONSIBLE FOR HIDING OUR ANCESTORS,” they say. “I DON’T KNOW IF I CAN TRUST YOU. PROVE ME WRONG.”

So begins a journey through a singular, sprawling, collage-like video game world of Black trans existence, set to hypnotic Auto-Tuned chants—a mellifluous incantation of “I DON’T WANT NO TERFS” among them. Created by artist Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, the game is part of the exhibition “I Promise to Burn Forever” at Public Functionary.

The interface continues to prompt me to make choices, and as I do, it becomes apparent that my earlier bristling was part of the point. Brathwaite-Shirley says as much in her artist statement. “HOW YOU FEEL IS THE MEDIUM I AM WORKING WITH,” she clarifies.

But the game isn’t interested in berating me. There is work to do. I am assigned to a security team and told I will be accompanying a Black trans femme on a journey. I continue to make choices, watching as each choice moves her across the screen. I accompany her across a wide, dark river. Finally, we arrive at our destination. I exhale, not realizing I’d been holding my breath, and wish her safety on her way.

“I Promise to Burn Forever” is a show about alternatives to institutional memory, resurrected Black trans ancestors, sovereign states constructed in metaphysical spaces, and a lot more. It’s a show that asks for your time, involvement, and participation—and, inextricably, your recognition that you have been involved and participating all along. The exhibition brings together the alternative archival practices of London- and Berlin-based Brathwaite-Shirley and Minnesota-based Oromo artist Agartuu Inor.

Curator Sati Varghese Mac was looking for clarity amid the devastation of the present.

“There are these massive atrocities happening around the world, and we need the things that we do and consume or engage with to reflect that, and to give us space to process and understand what our place is in all of it,” she tells me. “So I approached the show from that starting point, of being like, how can the work that we show speak to both the violence and pain, but also the coming together that we need right now.”

Varghese Mac found leaning into grassroots, alternative archival practices to be generative.

“Archives that are willing to be political, that are willing to acknowledge that you cannot be apolitical, but also that are interested in things outside of just information,” she explains. “The things that are left out because they don’t serve an objective narrative.”

“I Promise To Burn Forever” joins the work of Black scholars like Saidiya Hartman, who are rethinking what knowledge is remembered and what (and who) is forgotten or deliberately erased in colonial archives. Inor draws on Islamic principles and East African visual and architectural traditions in her interdisciplinary practice of beadwork, sculpture, and computational aesthetics.

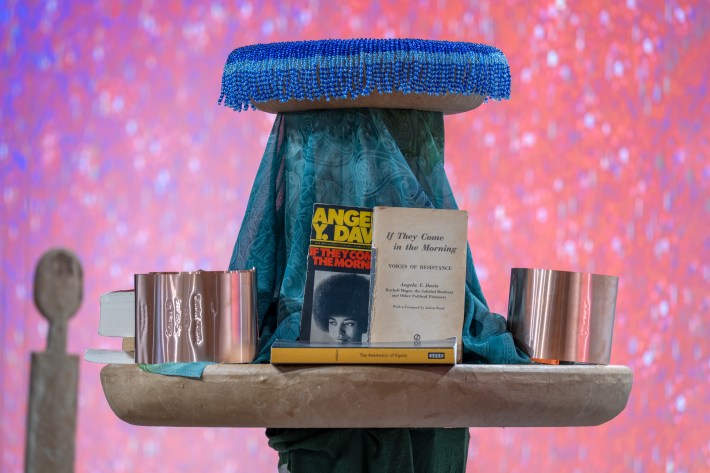

In “I Promise to Burn Forever,” she produces a sculptural monument to martyrs in the Oromo struggle for self-determination, which has long been met with violence by the Ethiopian government. The sculpture is strewn with copies of Black and Indigenous texts for liberation and healing, inviting visitors to linger, to read and learn and rest.

Inor describes how the construction of the sculpture was a communal process, the result of long nights with Varghese Mac and other collaborators during which they laughed, communed, shared stories, and got to know each other. This alternative archive then holds not only the books and the sculpture, but all the connections that were forged in its creation. Of the virtual, algorithmically generated Barakah Garden, a colourful landscape which gently flickers and blinks as it’s projected on a wall in the gallery, Inor describes wanting to make something that could be accessed and enjoyed by Oromo people anywhere in the world.

Both Brathwaite-Shirley and Inor are determined to fight erasure through destruction or assimilation by the state. They build vivid worlds teeming with all the fullness, complexity, humor, joy, and agency never afforded their communities by official, state-sponsored institutional records.

It's a testament to the strength of Varghese Mac's curation that Inor, an emerging artist, isn't eclipsed by Brathwaite's commanding, highly publicized work. A thoughtfully written exhibition text brings their practices into conversation, and Brathwaite's haunting music, playing across from Inor's monument, feels like an apt accompaniment. “I Promise to Burn Forever” is a spirited exhibition—painful, but also reviving and funny—that challenges and implicates, but doesn’t alienate, its visitors. Its aims might initially appear dense and highly conceptual, but they're ultimately born of a fiercely loving desire to honor those buried by history, and restore agency to those of us still here—and therefore possessing some say in how we will be remembered.

“Somewhere in a warehouse,” reads the exhibition text, “a data center devours our water to remember for us, recording every moment, promising, or perhaps threatening to burn forever.”

The artists in the show offer other ways to remember and resurrect; and, if all else fails, a scorching refusal to be lost to the dust of the archive.

“The title is really saying, if you burn me and my existence, I will burn forever,” Varghese Mac says. “You will not forget me.”

“I Promise to Burn Forever”

When: Through October 11, 2025

Where: Public Functionary, 1500 Jackson St. NE #144, Minneapolis

Find gallery hours and more information here.