There’s no greater benchmark of mainstream acceptance than Good Morning America.

Recently, the ABC morning show ran segments on: Petite Mom Has Her Hands Full with 40 Pounds of Babies; Gabby Petito Case Example of 'Missing White Woman Syndrome,' Experts Say; and Our Favorite Kim Kardashian Moments for Her Birthday. The summer concert series confirmed that, 20 years later, "Nelly is Still 'Hot in Herre.’”

And two weeks ago, GMA introduced its 3.8 million viewers, most of them likely non-radical by any metrics, to the term “Striketober.” Channeling his inner Studs Terkel, ABC News’s Terry Moran issued the following report to hosts Robin Roberts, George Stephanopoulos, and Michael Strahan.

“There is a new, militant spirit in the American workforce," Moran said. "Workers want more, and they're willing to strike to get it... workers notice the top executives and bosses are getting paid, and so for the first time in a long, long time, workers have the upper hand."

America on strike? 10,000 John Deere employees walk off the job amid contract dispute. @TerryMoran reports. https://t.co/0l9m4dPi0d pic.twitter.com/wPKNWrSYrT

— Good Morning America (@GMA) October 14, 2021

Striketeober is very real.

Just ask the 1,000 Warrior Met Coal miners who’ve been on the picket lines in Alabama since April. Or the 10,000 workers currently striking at 14 John Deere plants. Or the 1,400 workers striking at four Kellogg's factories. Snack makers at Nabisco ended a weeklong strike late last month, and IATSE—the union that represents film and TV production crews—narrowly avoided one this month. On Tuesday, McDonald’s workers at 10-plus nationwide locations staged a one-day work stoppage with pro-unionization overtones; around 2,000 Amazon warehouse workers just signed union cards in Staten Island, setting the stage for another labor showdown with the world’s largest retailer.

In total, more than 100,000 unionized workers flashed their fangs at employers in October, either striking or threatening to do so. Though historically it’s small, the current strike wave is towering by modern standards.

After decades of plummeting membership and influence, labor is having a moment. The U.S. workforce is only 11% percent unionized, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, down from a peak of over 30% in 1945. But 65% of the country supports unions, recent Gallup polling discovered, the highest percentage since 2003. And, in Joe Biden, labor has a surprise booster in the White House; breaking from decades of bipartisan consensus, the president has offered full-throated support of unions—rhetorically and legislatively. It's worth noting, however, that Biden has mostly retreated from labor's side during Striketober.

“People look at corporate America and they go, ‘These guys don’t care about us; they don’t care about our kids; we have to fight,’” says Donald “D” Taylor, the leader of hospitality union Unite Here, whose local chapter sparked a craft beverage unionization boom. “It’s a repudiation of the neo-liberal economics that both Democrats and Republicans have propagated for 40 years; all these companies feed at the trough of Wall Street. The kind of support you’ve seen for strikes—Nabisco, John Deere, Kellogg’s, the nurses, the coal miners—it’s getting back to the old principle of solidarity forever, and solidarity works.”

The momentum of Striktober can also be felt here in Minnesota. From hospitals to bookstores to skyscrapers, local workers are flexing union muscle like we’ve not seen in recent memory. Here are the stories behind their fights.

Healthcare Heroes, Negotiation Nonsense

The 48 union nurses at Plymouth’s Allina Health clinic know their old contract is terrible.

“It’s the worst contract," Sonya Worner, a registered nursing veteran of 20 years, says from the picket line during this month’s three-day strike. “All the other 12 contracts [at area Allina clinics], they get summer holiday pay at time-and-a-half… we’re the only nurses in the metro who don’t get holiday pay.”

That has become a major point of conflict during current negotiations, which were supposed to end by June 1. The Minneapolis-based health care giant—whose revenue approaches $5 billion and whose CEO makes $2.1 million—is steadfast in its refusal to pay the estimated total of $30,000 it’d cost to provide the nurses with paid summertime holidays, Worner reports. As negotiations intensified, the company began taking things off the table, including PTO. Ahead of the strike, Allina was forced to shut down its Plymouth urgent-care facility, resulting in the loss of hundreds of thousands in revenue, Worner estimates. (We asked Allina to confirm that figure, but never heard back.)

Why such fierce opposition to a peanut-sized ask? The company fears that precedent would entice non-union workers to ask for holiday pay, Worner says. “They told us, ‘If we give it to you, we’ll have to give it to them’—fine, give it to them!”

Due to sky-high nursing demand, the Plymouth nurses could jump ship and snag hefty sign-on bonuses at better-paying hospitals, Worner says. They’re determined to improve their current conditions out of “devotion to the community and the patients.”

An Allina Health PR rep offered Racket the following statement:

“Throughout negotiations, we have offered a comprehensive contract. Our current proposal, which was unanimously recommended by the union’s bargaining team, yet not ratified by its members, includes an immediate wage increase as well as other benefits. The current paid time off benefits offered would continue under a new contract. Looking forward, we are hopeful the union is ready to come to agreement on a new contract that prioritizes the health needs of the community, while also sustainably recognizing the contributions of our employees.”

When asked about summer holiday pay, specifically, in a follow-up question… crickets.

“The pandemic has exacerbated everything,” says Taylor of Unite Here. “If you look at who the essential workers were, they are largely people of color and women. And yet, the minute a company feels out in the clear, you wouldn’t know they’re essential with how companies treat them.”

(Adding further disrespect to essential workers, Minnesota politicians continue to bungle the distribution of $250 million in federal dollars intended to compensate frontline workers who kept the gears of capital spinning during the pandemic.)

The Allina nurses, who are among the Minnesota Nurses Association’s 22,000 members, aren’t backing down. Stacey Jacobsen, an RN with 25 years experience, struggles with the disconnect of being called a hero by Allina during the worst of COVID, then being treated with contempt during negotiations. “It’s very hurtful, it doesn’t feel good to be told you’re good enough to be subpar, contrast-wise,” she says from the picket line.

Jacobsen is inspired by the show of solidarity from her fellow nurses, around 90% of whom reject the contract, as well as from patients who’ve joined the picketing and donated food, candy, and thank-you cards.

She says the possibility of additional strikes is absolutely on the table.

“I think Allina, in some ways, wants to portray us as the ones who are harming the people we work with,” Jacobsen says. “We work with some really fantastic people—EMTs, RTs—and they’re hurt by this as much as we are. They’re not union, so they don’t have a voice, but we can be their voice, and that’s part of the reason we’re striking. Good patient care costs money. You have to treat the people that work the frontline as well as you wanna treat patients, and Allina is not delivering that.”

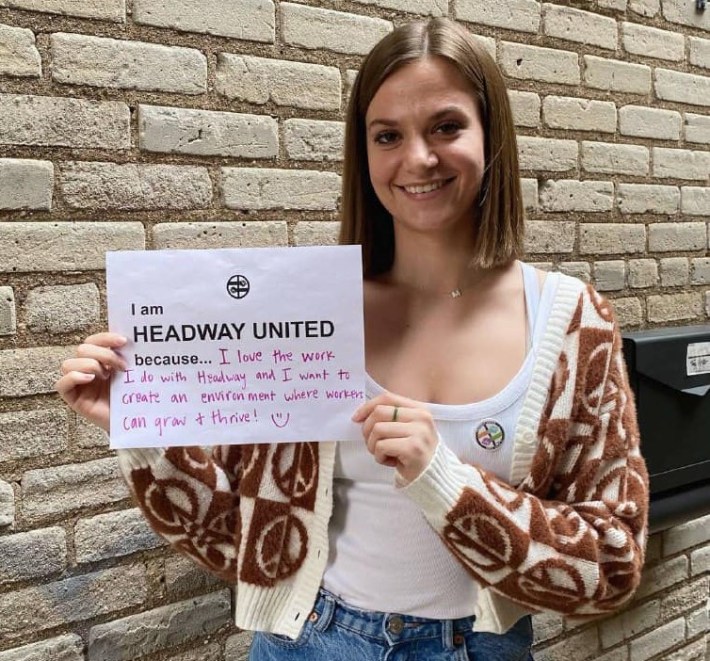

Labor Making Headway at Headway

Headway Emotional Health employs around 150 therapists, psychiatrists, caseworkers, and admin staff who specialize in outpatient therapy, in-school therapy, and other psychiatric services. Over a year ago, they began unionizing. By May, a majority had signed union cards. And, earlier this month, card-wielding workers informed the Richfield-based nonprofit company of their intent to unionize, though the cat was already out of the bag.

“Management has been leading anti-union rhetoric for some time now,” says Maggie Murray, a school-based therapist who’s been with Headway a little over a year. “Back when they found out our intent to unionize, they set up an anonymous question box where you could submit questions about unions and they’d provide ‘answers.’”

New-employee orientations now include “a pretty strong anti-union pitch,” she adds, and anti-union emails appear in employee inboxes with regularity. Unsurprisingly, the company declined to recognize its unionizing workforce, one that hopes to organize under the umbrella of OPEIU Local 12—the local chapter of the Office and Professional Employees International Union. Headway CEO Patrick Dale has since received almost 200 letters encouraging the union effort, Local 12 reports, from clients, community members, and lawmakers.

“Headway strongly supports our employees’ right to explore whether unionization is the right call for them and their families,” Dale tells Racket. “We are committed to making sure they have a full and fair opportunity to make a democratic decision by voting on the issue.”

Given the absence of voluntary employer recognition, Headway workers will have to take the more laborious route: An election overseen by the National Labor Relations Board that will determine whether their union legally exists.

How’d it get to this point?

Money, benefits, lack of worker input, and high turnover, Murray says. There are staffers who have never received raises after five years with Headway, she says, and the “revolving door” of therapists is detrimental to patient care. Murray says many of her peers could quit and get better-paying jobs with little effort, but they remain because “we love Headway, that’s why we’re unionizing.”

“We’re not disgruntled employees, we’re not money-hungry: We believe in the Headway mission, and want to stay there long-term,” Murray says, echoing every other worker we interviewed. “There are things that we are unwilling to accept, and want a seat at the table to change so that it is a thriving business.”

The wind-in-the-sails of Striketober has been impossible to ignore, Murray says.

“Hearing about strikes and unionizing in the news, it feels like there’s a lot of momentum,” she says. “There were always things brewing under the surface, but over the pandemic and with the murder of George Floyd, we’re seeing how, on a systematic level, how we can have more power. We’re just not willing anymore to take policies that are handed down.”

A New Chapter for Unions?

Gutted by decades of globalization, the historically unionized U.S. manufacturing sector offers few new leads for organizers. So labor is getting creative. You might not have expected the Minnesota Historical Society to unionize, but it’s happening here and at museums around the country. Same for the Twin Cities craft-beverage sector.

Half Price Books is the latest non-traditional union prospect.

HPB worker David Gutsche wasn’t sure if his organizing pipe dream was practical, let alone legal. For the past five years, Gutsche and his co-workers at Roseville’s Half Price Books have murmured and grumbled in private; the word “union” started getting floated more and more often.

“After a while, I realized, I’m going to actually ask somebody who works at a union,” Gutsche says, “and say, ‘Hey, what if a retail establishment did have pretty good retention, and loyal employees who really did like their jobs and want to fight and make it better… is it possible to organize one or two stores out of a big corporation, is that even legal?’”

United Food and Commercial Workers Local 1189, which represents 10,000 members throughout the Midwest, answered resoundingly in the affirmative.

“In fact, they told us it’s encouraged,” Gutsche says with a chuckle.

Around 30 workers from HPB’s Roseville and St. Paul shops met with UFCW reps at George Floyd Square this past May Day, an apropos date if there ever was one. An organizing committee was formed, and the workers “slowly built power in secret,” Gutsche says.

Earlier this month, workers let that secret out: More than 75% of the employees at each store had signed union cards. About 10 workers at the Coon Rapids location joined the push last week, meaning three of HPB’s six Twin Cities locations are now unionizing.

The easy next step—voluntary employer recognition—was quickly snuffed out. “‘I cannot and will not support a union’ is exactly what we heard from our store manager, which was not a huge surprise,” Gutsche says. Next step: An election overseen by the NLRB, just like at Headway. One will be held in the coming weeks, and should the yeas outweigh the nays, Minnesota will become home to the first union shops among HPB’s 120-plus locations.

“It’s unfortunate for Half Price Books that they don’t see this as an opportunity,” says Claire Van den Berghe, UFCW 1189’s director of organizing. “This could be a great way to distinguish themselves from that shadowy competition of theirs, Amazon.com.”

HPB, the country’s third largest bookstore retailer, did not respond to Racket’s request for comment.

Gutsche, on the other hand, was eager to talk about why he spearheaded the first-ever union effort inside HPB. He’s loved his job for nine years, but low wages make it difficult to view as a long-term career option. Some 20-year HPB veterans are still making $16 an hour, Gutsche says. “Upsetting, confusing, and frustrating” behavior from the company during COVID-19, including layoffs that “lacked transparency,” amplified worker grievances, he adds.

“The general idea of workers having a seat at the table to appeal and improve our working conditions,” Gutsche says, summarizing his desire to unionize. “To at least have a dialogue, in the negotiation of a contract, is going to be huge for worker power at Half Price Books”

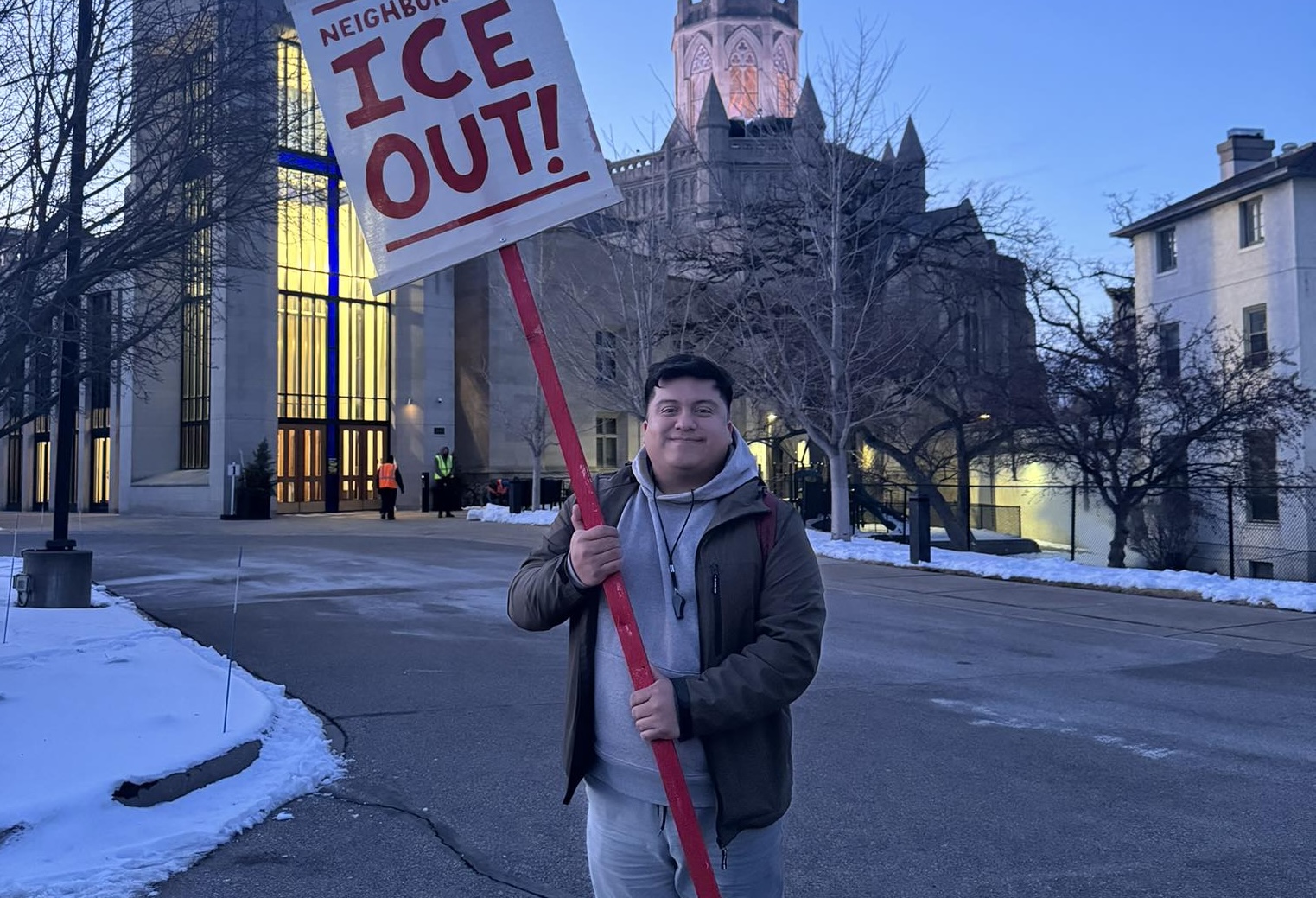

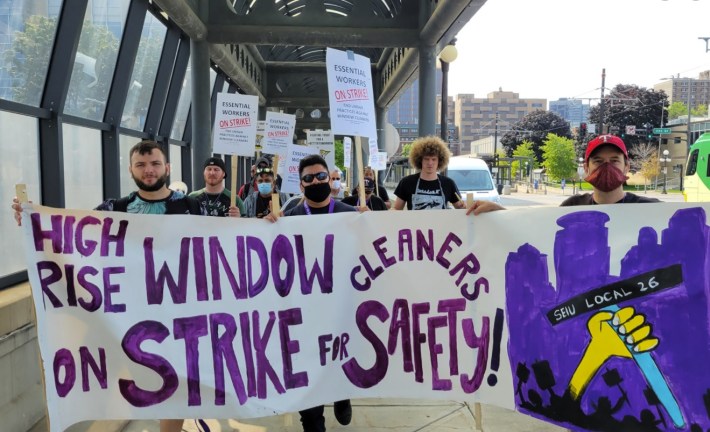

Squeegee Solidarity

The biggest Striketober victory might be IATSE, the union repping 60,000 TV/film production crew members that averted a strike last week. But, considering the shaky and tense state of their tentative contract agreement, leaders at IATSE’s local offshoot politely declined to take a victory lap with Racket.

So we’ll risk offending calendar purists and look back to late August, when the high-rise window washers who keep your skyscraper gleaming won a new contract following a 10-day strike. It’d take a brave scab to dangle 50 stories in the air while balancing cleaning gear.

Around 40 workers, who count among the 8,000 represented by Minneapolis union SEIU Local 26, scored 12% wage increases, reportedly placing them only behind their New York City counterparts with regard to pay. The four-year contract also includes an apprenticeship safety program plus increased sick and disability pay.

“The last 10 days were so beautiful, and I’ll never forget the unity for the rest of my life,” window washer/union steward Eric Crone said in a statement following the victory. “From my fellow window cleaners to people on the street honking horns and pumping their fists, the solidarity that came out is something I’ll treasure forever. Our strike showed that no one will just give that to us, but you have to stand up and fight for what you deserve. I hope our strike, and our strong new contract, show other essential workers that when you band together and stay the course, you can get results.”

Labor still faces an uphill battle. Right now, a “reserve army” of unemployed workers, to use Marx’s term, is forcing capital’s hand, resulting in higher wages being dangled like carrots to keep the status-quo humming. The PRO Act, the most labor-friendly piece of legislation in decades, is currently working its way through Congress with presidential support; it would help level the worker vs. industry playing field that’s been tilted in favor of big business since well before Reagan fired the air-traffic controllers. Renewed willingness to strike is essential, according to Unite Here’s Taylor.

“The labor movement had unilateral disarmament for a while by not striking—why would you take a weapon off the table when the employer has so many weapons?” he says. “Labor needs to go much bigger and much bolder in organizing; workers are crying out to have a better deal.”

Worker anger is unquestionable. Can labor leaders seize on the generational opportunity that anger presents? That’s the big question as we turn the calendar from Striketober.

“Workers right now are fed up and tired of being taken advantage of,” says Brahim Kone, SEIU Local 26’s secretary-treasurer. “Rent is skyrocketing, everything is expensive, and we call workers essential, but when it comes to pay, they’re not that essential. We need to coordinate our fight, and create a big voice among various movements.”