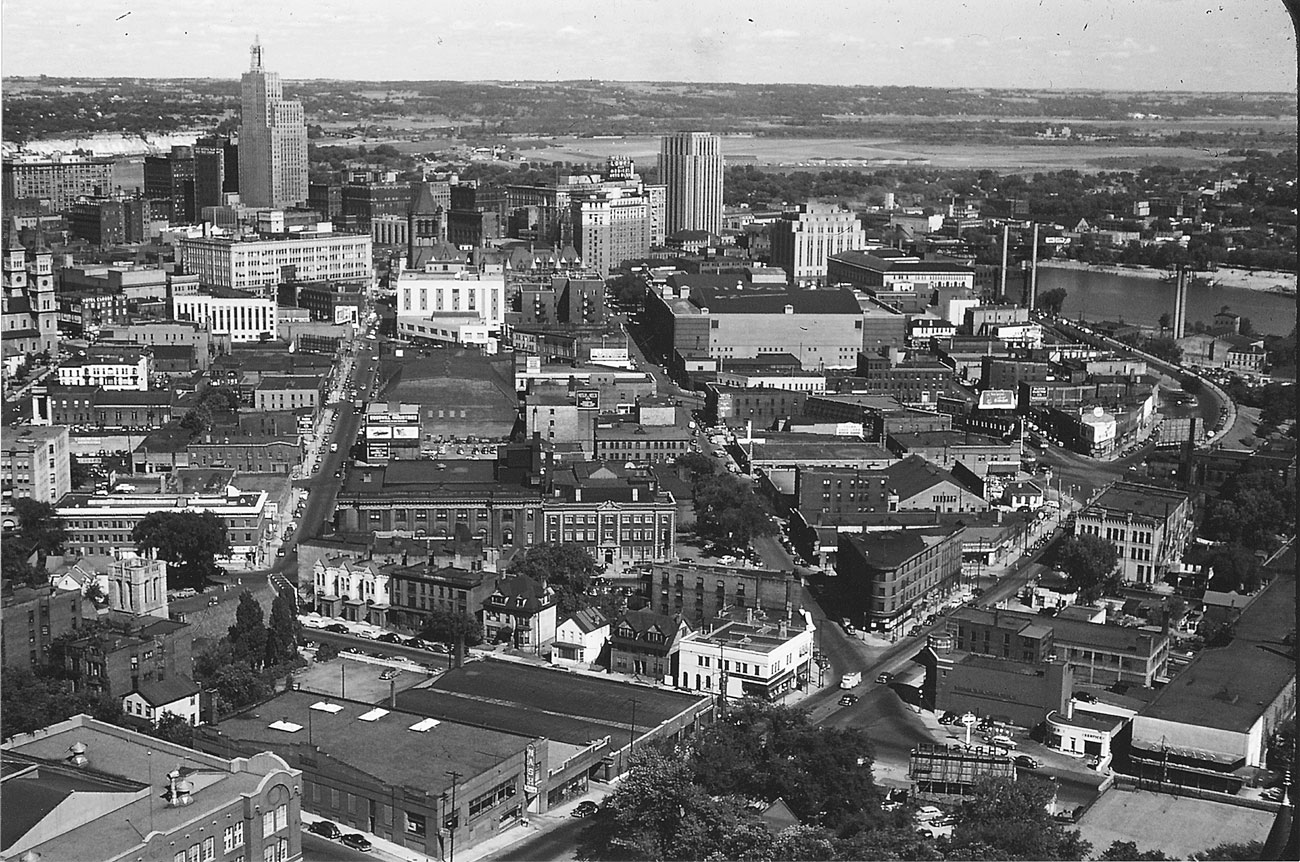

If you stood on the steps of the cathedral in 1950 and looked down at St. Paul, you would have seen a dense and varied city stretching out block after block to the Mississippi River. Twenty-five years later, the view would be almost unrecognizable.

Between the cathedral, the state capitol, and downtown lay one of the city’s oldest working-class areas, a maze of streets coming together willy-nilly. Factories, apartment buildings, old Victorian mansions, hovels, bars, recreational clubs, and corner shops were all mashed together and full of people. Just to the south, the Seven Corners neighborhood lived up to its name, a collision of narrow, busy streets and streetcar tracks forming St. Paul’s liveliest jumble, surrounded by aging buildings caked in crumbling detail.

Attracted by a city full of department stores, downtown crowds were thicker than anything this side of the State Fair. Downtown was the shopping center for the whole eastern half of the Twin Cities, the place for errands and work and where all the streetcar lines crossed.

The result was a logjam of people, goods, and vehicles. As one newspaper columnist described the sight: “Close up, the city is lines of cars, darting in and out of threading traffic; it is the people who pour out of the buildings at noonday, who form a glut of humanity at Seventh and Wabasha, who jostled each other amid a rustle of packages on the buses that weave out of the Loop at 5 p.m.”

But little of the old city would last much longer, as different patterns of urban development would be trumped by plans and progress. The old walking city, with its diverse chaotic neighborhoods on the edge of downtown, was targeted for removal. So too were the streetcars—on their last financial legs, slated to be replaced with buses and the speed of the motor era. The new St. Paul, driven by huge postwar federal investments, would feel radically different from the old, leaving only pockets of the older city landscape behind.

The city’s urban patchwork hid a deeper truth about American cities. Vague concerns over immigration and thinly veiled racism intensified during the labor shortages of the early twentieth century, which saw increasing numbers of immigrants from places like Mexico and southern and eastern Europe. In addition, by the early twentieth century, the Great Migration of Black Americans coming north from southern states had begun. St. Paul’s Black community grew steadily, increasing racial anxieties for white residents raised on intolerance.

Beginning around World War I, many of St. Paul’s residential developments began to include special covenants in their mortgages, restricting future sales of homes to anyone who was not white and Christian. These racial covenants reinforced the class stratification and ethnic segregation that formed the de facto borders of St. Paul’s distinct residential neighborhoods.

Living with de facto racial segregation was an everyday experience for St. Paul’s communities of color, including the small Native American, Mexican-American, and Asian-American populations, but especially for the city’s tight-knit Black community. The vast majority of Black St. Paulites lived in only a few neighborhoods, areas just on the edge of downtown and stretching to the east from the capitol and cathedral. To move outside of these segregated confines was to challenge the unwritten rules of St. Paul’s white society. It was rarely attempted, and with good reason.

The unspoken truth of St. Paul segregation burst into the open in 1924, when a Black lawyer and his activist wife, William and Nellie Francis, bought a house in the middle-class Macalester-Groveland neighborhood. Nellie Francis had spent years advocating for the rights of both African Americans and women, including lobbying the legislature to pass anti-lynching laws. William Francis was earning good money working for the railroads, and the couple saw no reason why they shouldn’t live in one of St. Paul’s nicer neighborhoods. They bought a modest house on Sargent Avenue, but when their neighbors realized what was happening, the community erupted in a fit of organized racism.

The Francises lasted in the home for less than three years. Bigoted neighbors quickly formed a neighborhood “improvement association” and tried to buy them out. After they refused, the deluge of harassment began: marches in front of the Francis home, threatening phone calls, and, twice, burning crosses in their yard. The Francises had to hire a security guard to keep the racist mob at bay, and the standoff ended only when William Francis was appointed to a foreign service position in Liberia. Their horrid tale is one of many similar stories of the racial lines undergirding the city, stories that rarely made it into the historical record.

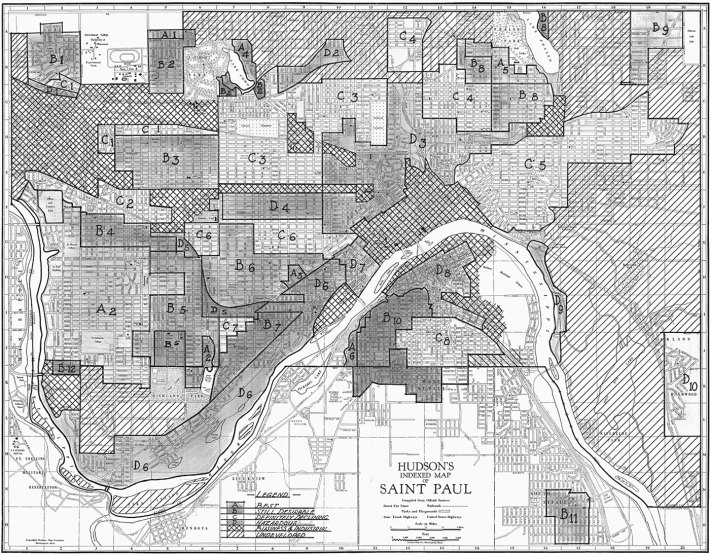

Inspired by early urban planning and sociology, with the hope of enacting homeownership policies that would boost the economy, New Deal inspectors began studying urban neighborhoods across the country in 1932. Unfortunately, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) inspectors harbored biases that lay the foundation for generations of racial inequality in America. Ostensibly grading which neighborhoods were good investments worthy of federal insurance, they baked into their assumptions racist prejudice about age, diversity, and heterogeneity of communities. All-white, single-family residential areas were given an A or B rating, while older, mixed-use, or racially diverse areas were marked with a D and colored red. These redlined parts of town—including most of St. Paul’s diverse, working-class neighborhoods—became ineligible for federal insurance. Overnight it became almost impossible to sell or buy a house if you were not white.

These New Deal maps mirrored the city planning values that guided St. Paul’s postwar transformation, visions of an ideal city that stemmed from the poverty of the Great Depression. At the time, urban reformers had deep concerns about urban poverty and pathologized dense neighborhoods of fast-growing cities like New York, Chicago, and (even) St. Paul. Most believed that crowded apartments, intergenerational communities, and multiethnic neighborhoods led to immorality, vice, and crime, assumptions stemming from prejudice about immigration and race.

This extract from Bill Lindeke's St. Paul: An Urban Biography is reproduced with permission from the Minnesota Historical Society Press.