I wake up Saturday morning unaware that I’ll soon be getting on-the-job training as a nurse, operating in an ad-hoc field hospital out of a local brunch joint.

The day begins as most have over the last two months: wake up, check Signal, decide where and how to help amid the ongoing federal immigration occupation of Minnesota. Except that today, around 9:30 a.m., Minneapolis’s Uptown/Whittier rapid response chat is aglow with warnings. Another shooting, possible killing by the feds. In a different chat, a link begins circulating to a video of the apparent execution. It’s bad.

By about 10:30, I arrive at 26th & Nicollet, near where the Trump administration’s invading goons have fatally shot Alex Pretti. The air is already heavy with tear gas and ire. An on-site responder on a bullhorn announces that there are two medics inside of Copper Hen Cakery & Kitchen, the farmhouse restaurant and bakery. With my digits already seizing in subzero temps, I figure there must be hand warmers and head in.

Inside Copper Hen, an older pair of nurses introduce themselves. One asks if there are more medics in the building, explaining that he’s going to show us “right fucking now” how to treat someone impacted by chemical irritants. I tepidly raise my hand to join the fearful but now dutiful care team in the bathroom down the hallway.

The nurse is armed with no more than four pairs of purple nitrile gloves and a plastic water bottle. He instructs a woman in tie-dyed pink sweats, her eyes raging and red around their edges, to take off her jacket and sweatshirt, as any prolonged period with chemicals on your body can cause excruciating damage. The riled-up and activated medic continues his instructions.

Within seconds of treating our first patient, throngs of neighbors begin filing into the restaurant, choking on tears and snot from the blocks-long cloud of tear gas. The two bathrooms past the coffee bar are now filling up with our team, who instruct the new patients: First, gargle with water, then spit. Repeat. We each take a comrade into our hands, gently tilting their heads to the side so that water flushes the irritants down and away from their eyes. Turn the head in the other direction. Repeat.

Before long, all of the tables in the restaurant are filled with protesters, observers, and media looking like they just got off the worst ski-lift ride of their lives. We dedicate one table to some paltry first-aid kits; the staff is still hard at work, ferociously running around with cinnamon buns and coffee orders. This is our field hospital, but it’s also still a restaurant.

Half-empty water bottles surround the bathroom sinks, and we struggle to remember which ones people drank from and which were just for eyes. There are metal pitchers too, just in case, and the floors are sopping wet. I take the overflow patients to hover over the toilets as a secondary location for flushing out eyes. We are getting buried.

Cases of water are flying toward the back-of-house while a former EMT, now a law student, directs traffic at the front door: “If you are warming up, move to the right. If you need medical attention, straight back.” Every few minutes, I gently escort the afflicted towards whichever bathroom currently holds the fewest people.

It’s around noon now, and three physicians in high-vis neon jackets join us in the first bathroom. We less initiated “staff” breathe a quick sigh of relief that we have bonafide doctors on site now, after about a half hour of our somewhat crack decentralized M.A.S.H. unit. We familiarize each other with what minimal supplies we have on hand as the doctors deploy their heavy-duty kits, ready to step in for higher intensity traumas. Fortunately, throughout the whole day I only witnessed one wound from a flash-bang being tended to by other plain-clothed physicians. Later a psychiatrist joins our ranks as well.

Over the next few hours, the crowds grow. I ask for periodic updates from the outside: Are the state police still here? Is ICE gone? When is the National Guard coming? Even in periods of relative calm, there’s an on-edge feeling that the situation will keep escalating, that more people will come in waves.

Sure enough, 30 or more folks rush the front door. I take an East African reporter for a local news outlet down the hall and position his head over a waste bin ready to be flushed; this is now our fifth or sixth auxiliary wash station. We hear that ICE is now coming up the corridor with more munitions and tear gas, and a dude in full riot-protection gear carrying the new state flag guards the back door to the alley. He slides a few people in, and with them come more bangs and toxins. Remembering the airline instructions to put on your own oxygen mask before helping others, I throw my respirator on.

In a rare moment of quiet, our crew of about a dozen asks the kitchen staff if we can use the prep-station as an equipment closet. I help organize gauze, bandages, handwarmers, mylar blankets, saline, and gadgets I don’t have the medical experience or words to describe. I have no medical training or expertise, which I continue to remind our team throughout the day; they shrug it off and reassure me that being able to care and communicate is the job, at least for right now. Our more senior staff determines that the baked-goods rack can be used to better organize our supplies. The Copper Hen is now a hospital.

The Copper Hen’s staff of six or seven is still crushing orders, clearing glasses, and cranking the espresso machine into overdrive. The chef asks if we’re hungry, and when I nod, he fires up 15 biscuit, egg, and bacon sandwiches delicately wrapped in tinfoil. I later learn that he saw Pretti’s death earlier that morning. I also learn that Copper Hen’s owner’s mother just had bypass surgery within the last 24 hours. She snacks on cheese as I wonder if and when the Hen will close and we’ll have to relocate our operations.

They never do. All along Eat Street, businesses like Glam Doll Donuts, Pimento Jamaican Kitchen, My Huong Kitchen, and b. Resale have opened their doors for first responders and observers, handing out respirators and toe warmers or donuts and coffee.

As the hours flash by, we receive more supplies from veteran EMTs who have been doing laps outside on the frontlines all day: saline plungers, pediatric ambu masks, saline bags with IVs. A couple groups of friends drop off Ibuprofen, extra-strength Tylenol, blankets, wound wash—anything they can get their hands on.

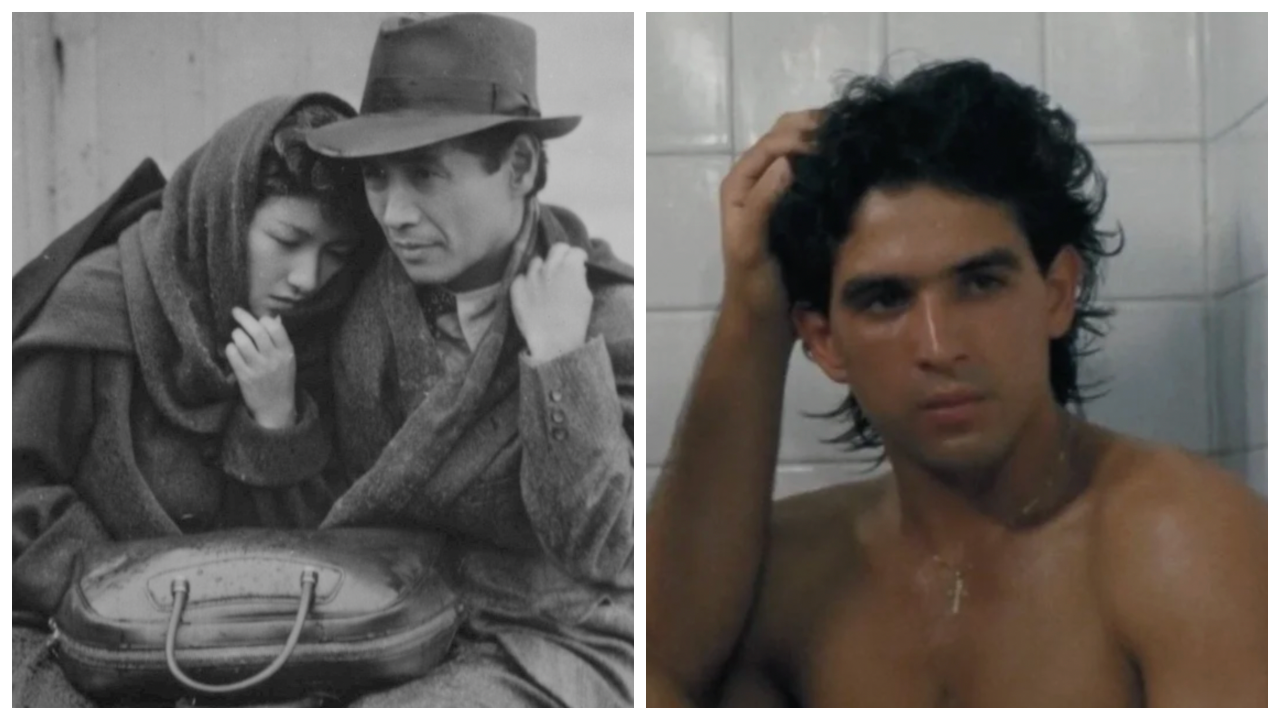

Halfway through the day, during a lull, we officially learn Alex’s name. I share his picture on my phone to my team as we huddle by the baking rack. His face is unmistakably generous, that bearded grin. He was an adventurer, and, as we soon learn, an ICU nurse at the Veteran’s Affairs hospital. The parents of one of the doctors onsite, who had also been tending to a woman who was having a full-blown anxiety attack, shivering uncontrollably and smothered in jackets, immediately recognize Alex. We all began to tear up, and then, we simply carried on with the work in an unspoken agreement to honor Alex’s life.