In the 1930s, Minnesota had two main parties: Republicans and Farmer-Laborers.

Founded toward the end of World War I, the Farmer-Labor Party was an outgrowth of the progressive Nonpartisan League, which took power in North Dakota using the Republican ballot line and had set up a national headquarters in Saint Paul. The FLP united not just its namesake agrarians and urban proletariat, but, in the spirit of the Popular Front, social democratic reformists with revolutionary Marxists.

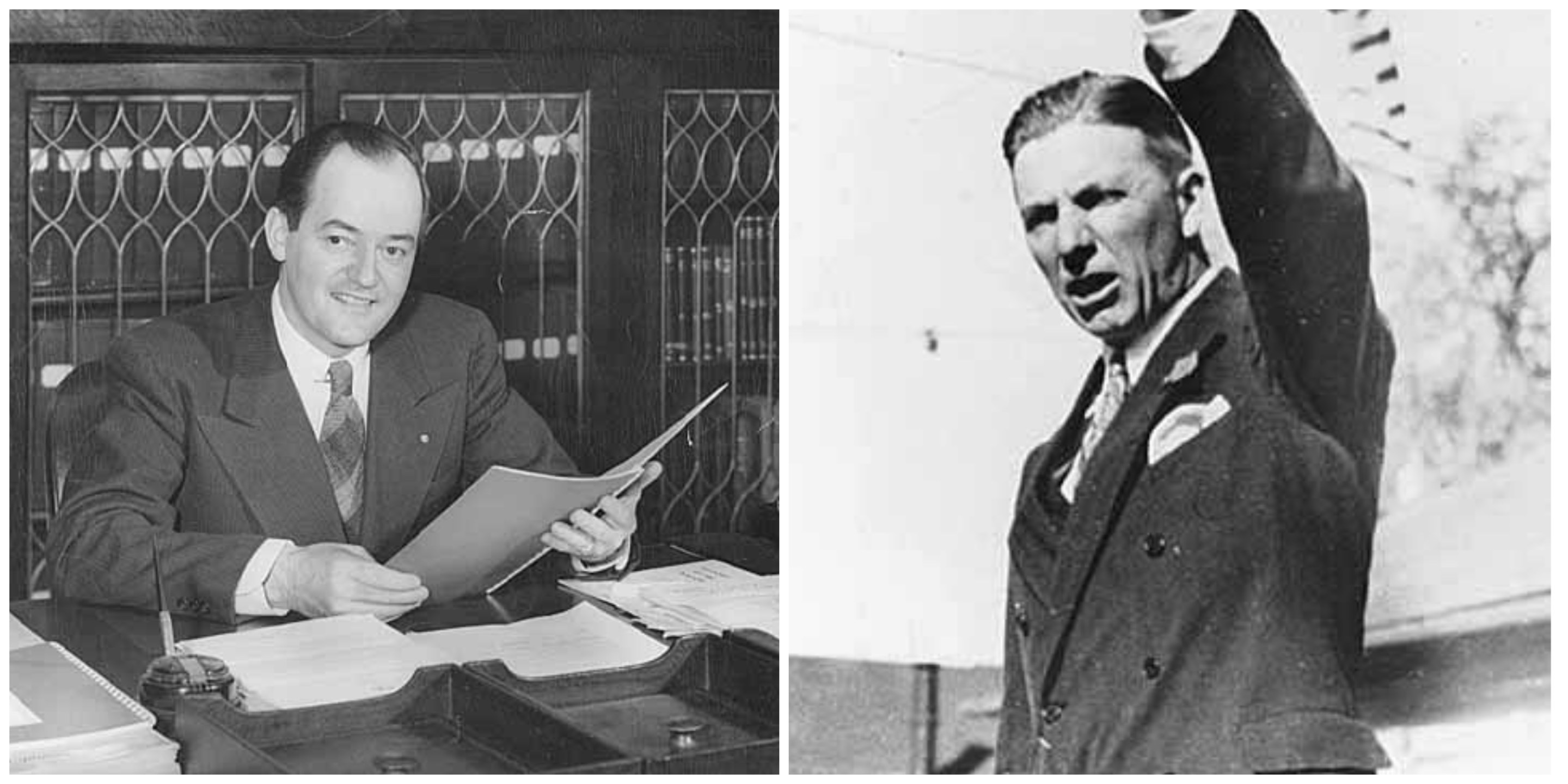

In 1930, the Farmer-Labor Party won the governorship with the legendary Floyd Olson, a left-wing Hennepin County Attorney who had caused a stir by forcefully defending a group of Minneapolis workers accused of dynamiting an anti-union contractor's home. Olson permitted communists and socialists to participate in the Farmer-Labor Party, often to the chagrin of populist liberals, but he also jettisoned controversial planks from the FLP platform like recognition of the USSR, public ownership of key industries, and (odder in retrospect) unemployment insurance and a 40-hour work week. A useful reminder that things seem a lot less radical when you already have them.

Olson is remembered for his shrewdness and keen sense of the Farmer-Labor project’s constantly fluctuating constraints. As governor, he enacted progressive taxation, a moratorium on farm foreclosures and built the FLP into a very powerful political force, at least within Minnesota’s borders. In 1932, third-party advocates urged Olson to take the Farmer-Labor Party nationwide and run for president as its nominee. Acutely aware of the dearth of third-party organization in just about every state except Minnesota, Olson demurred and instead cut a deal endorsing the Democratic nominee, progressive New York Gov. Franklin Roosevelt.

Olson went on to play a decisive role in the 1934 Minneapolis Trucker Strike, though on whose behalf he acted depends on who you talk to. To Trotskyists, whose fellow travelers masterfully organized the strike, Gov. Olson’s decision to bring in the Minnesota National Guard was a betrayal that resulted in the arrest of labor leaders, and allowed trucks to move. But to Farmer-Labor devotees, the National Guard’s real objective was to protect the striking Teamsters from the violent, business funded Citizens Alliance; a maneuver which allowed Olson to broker a resolution that achieved formal union recognition. Lest his left-wing critics doubt Olson’s bonafides, at that year’s FLP convention, the governor tested the bounds of his popularity by allowing a stridently socialist platform and proclaiming, “Now I am frank to say I am not a liberal… I am what I want to be—I am a radical.”

Floyd Olson was in the midst of a campaign for U.S Senate when he died unexpectedly from stomach cancer in the summer of 1936. He was just 44. The Farmer-Labor Party was never quite the same. A nasty power struggle broke out between his successors, Hjalmar Petersen and Elmer Benson, who managed to hold the Governor’s Mansion for all of two years until moderate Republican Harold Stassen took over in 1938. As war with the Axis powers neared, Minnesota’s isolationist undercurrents came to the fore and brought anti-Roosevelt Republicans to power.

By 1940, the FLP had lost every seat they once held in Minnesota’s Congressional delegation and their lone U.S Senator, Henrik Shipstead, had become a Republican to bolster the GOP’s anti-war wing. Meanwhile, the American Federation of Labor, a onetime ally of the FLP, had split, confusing the party even further; and with the Democratic-led New Deal at its zenith, the need for corresponding farmer-labor parties around the country felt all the less urgent. Just as Soviet Russia had been seriously tested by Stalin’s pursuit of “socialism in one country,” the FLP was learning the hard limits of “third-partyism in one state.”

As Minnesotans are usually reluctant to admit, our “Land of 10,000 Lakes” figure may or may not include some exaggerations. In the early 1940s, if the Farmer-Labor Party was a pond, then the Minnesota Democratic Party was a puddle. Since the 1860s, Minnesota Democrats had struggled to shake their party's association with the Confederacy, which took the lives of nearly 3,000 Minnesotans in the Civil War. Democrats hadn’t won a statewide race since 1914, after which they were buried by the FLP as the main opposition to Minnesota Republicans, their support base confined to the Irish ghettos of St. Paul and Minneapolis. But now, as the Farmer-Labor Party faded fast, Minnesota Democrats gained new relevance. With Republicans in control of the Governor’s Mansion and both U.S. Senate seats, it was increasingly clear that Minnesota wasn’t quite big enough for two left of center parties.

In 1944, FDR, gearing up to campaign for an unprecedented fourth term, insisted that Minnesota’s Democrats and Farmer-Laborers merge. FLP stalwarts like Susie Williamson Stageberg vehemently opposed a fusion party but was outnumbered by her peers. Elmer Benson, to this day Minnesota’s most radical governor, was now out of office and represented the Farmer-Labor Party in negotiations with the Democrats. In April 1944, the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party was born.

The next year, the new party’s prime spokesman came through in the profile of Hubert H. Humphrey, who was decisively elected mayor of Minneapolis. Humphrey was an effective leader who made no secret that he was a partisan of the DFL’s “Democratic” wing. Being the most prominent elected DFL official in Minnesota at the time, he showed up to give a keynote address at the 1946 party convention in St. Paul, but was booed off the stage by Farmer-Labor diehards who weren’t about to cede control to Humphrey’s upstart liberal faction.

Tensions grew over the next two years, as Humphrey burrowed in his heels and formed a “diaper brigade” of young party moderates, mostly constituted by himself and DFL Executive Committee Member, Orville Freeman. The dynamic was characterized by a 1947 official party letter to Humphrey, the first draft of which was written by Freeman with a congratulatory tone. But when the Farmer-Laborers who still dominated the Executive Committee went through it with their red pens, all references to “outstanding leadership” were struck from the text.

A year later, in 1948, the ambitious Mayor Humphrey made it his mission to take one of Minnesota’s Senate seats back from the Republicans. But first, he had to get through his own party’s left flank. Humphrey activated his liberal anticommunist organization, Americans for Democratic Action, to red-bait radical Minnesotans out of political life. As a leaflet from Humphrey’s faction posed: “Will the D-F-L party of Minnesota be a clean, honest, decent, progressive party? Or will it be a Communist-front organization?”

To truly weed out the left, Humphrey’s crew would need to win control through the labyrinthine party caucus system. Ahead of the April 30 DFL caucuses, Orville Freeman organized a parallel formation of anticommunists, most of whom had never attended a party meeting, to complete the purge. In Hennepin County, Lester Covey, the County chair and an ally of Humphrey’s, rearranged the caucus locations to favor the Democratic wing. The move outraged party radicals, who opted to hold their own caucuses at individual precincts per tradition. But Humphrey’s faction won the night. As Minnesota historian Rhoda Gilman noted, “Using tactics borrowed directly from the leftists of the party, they swept the DFL all the way to the state convention in the Spring of 1948.”

Humphrey struck his most decisive blow by exploiting a hemorrhage over the party’s presidential nomination. For well over a decade, the presidential question had been non-controversial for Farmer-Laborers who readily endorsed FDR, often with reciprocal support. It was his initiative, after all, that brought the two rival parties together. But with Roosevelt gone and Nazism defeated, the DFL, along with the broader Popular Front, had lost its common purpose.

Harry Truman, who inherited the Presidency in 1945 after FDR’s death, was deeply unpopular among Farmer-Laborites who viscerally remembered how he was forced onto the ticket in 1944 to replace a man even more of their ilk than Roosevelt, Vice President Henry Wallace. In 1948, Wallace left the Democrats to rehabilitate the dormant Progressive Party as its presidential nominee. His campaign attracted what was left of the Popular Front, communists and social democrats unhappy with Truman’s initiation of the Cold War, tepidness on Civil Rights and failure to marshal burgeoning strike activity into a cohesive movement. Naturally, Wallace’s campaign drew a great deal of support from the DFL’s left, including from Elmer Benson who served as campaign manager. Despite this, Hubert Humphrey was not only able to secure the DFL Presidential nomination for Truman, but used the party Steering Committee to disqualify Wallace supporters from Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party participation.

Having been banned from the official DFL convention in Brainerd, the Farmer-Labor left held their own protest convention in Minneapolis as the “Progressive Democratic Farmer Labor League” where they nominated Wallace and Senate candidate James Shields. This was their last gasp. After a round of legal jousting, Humphrey and Truman made the DFL ballot line, cementing the Democratic wing’s dominance over every aspect of the party but the last two words in its name. Over the next several decades, bitterness among old Farmer-Laborites grew, over both the purge and their own decision to fuse with Democrats in the first place. Elmer Benson, who lived to 89, decried Humphrey as a “war criminal” and “ballyhoo artist” in one of his final interviews and expressed regret over the 1944 merger: “I think it was a mistake because the party became part of a larger party that’s been taken over by political hacks.”

In retrospect, it’s hard to imagine the Farmer-Labor left maneuvering their way into some better outcome. Aside from North Dakota, which is still home to the “North Dakota Democratic-Nonpartisan League Party,” there were very few factions of radicals across the country sharing state parties with Democrats for the Farmer-Laborers to coordinate with. The Progressive Party may have felt like it could be built into a national alternative for a time, but it netted a mere 2% of the vote in 1948 and collapsed from infighting a few years later. And while it was likely a better move for the FLP to remain independent of the Democrats, it’s not at all clear that they would have retained second party status and not been overtaken by Humphrey and his coterie anyway.

Some argue that by merging, the Farmer-Laborers did bring the Democrats leftward, at least on the issue of civil rights, which Hubert Humphrey boldly embraced from his mayoralty onwards. This may somewhat explain the DFL’s position today, one or two notches to the left of the average state Democratic Party, as displayed by Minnesota’s recent universal school meals law and Gov. Tim Walz’s pronouncements on trans rights. That would likely be cold comfort to the original Farmer-Laborers and their vision for a “cooperative commonwealth.” Such a vision, however, is increasingly popular across America once again, including in Minnesota where voters have elected over ten current Democratic Socialist officeholders using the DFL ballot line. Ever so often, DFL moderates float shortening the name to “Minnesota Democratic Party.” But with changing political winds and dedicated organization, perhaps one day an opposite edit will come about and allow the “Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party” to rise again.

Sources:

Books:

- The Political Career of Floyd B Olson by George Mayer, 1951

- Stand Up!: The Story of Minnesota's Protest Tradition by Rhoda Gilman, 2012

Articles:

- "The caucus that changed history: 1948’s battle for control of the DFL," MinnPost, 2016

- "The ‘Mother of the Farmer-Labor Party’ didn’t really want to add the ‘D’ to the beginning," MinnPost 2017

- "Socialist Elmer Benson Dies at 89: Radical Played a Prominent Role in Minnesota Politics," L.A. Times, 1985

Podcasts:

- March of the Governors #24: Elmer Benson, Ramsey County Historical Society

- March of the Governors #22: Floyd B. Olson, Ramsey County Historical Society