On the night of November 3, 1998, the Ventura family drove to Canterbury Downs under a full moon for an election watch party to celebrate Jesse’s Reform Party gubernatorial campaign. Looking out the window at a hint of Northern Lights bouncing off the moon’s glow, Jesse’s 19-year-old son Tyrel remarked, “Dad, something strange is gonna happen tonight.”

A few hours later, the former pro wrestler stood before a sea of neon campaign signs and declared victory to his elated supporters and a stunned international audience, bucking tradition by not waiting for his two shellshocked opponents to concede. Ventura’s election as both a celebrity and third-party candidate quickly became the stuff of legend in Minnesota and beyond.

The following four years of wild, unprecedented tripartisan governance? Those are often overlooked.

Ventura may have been viewed as a political novice in 1998, though his first foray into politics actually came eight years earlier when he was elected mayor of Brooklyn Park. That candidacy was sparked by opposition to a local developer who had designs on a wetland with the city council’s blessing. In a race that presaged Ventura’s later career, Brooklyn Park politicos laughed off his interest in the project and thereafter his candidacy, but were aghast at Jesse’s 26-point victory over an 18-year incumbent in 1990. Mayor Ventura’s powers were limited given Brooklyn Park’s weak mayor system, which made him little more than an extra vote on the council.

To say he “shook things up” in the suburb’s political dealings, however, would be a massive understatement. Mayor Ventura made fast enemies with his colleagues in city government, who often neglected to refer to him as mayor and took umbrage at the wrestler’s unconventional dress—Jesse would wear bandanas and T-shirts, sometimes under a sport coat, to council meetings. Ultimately, Ventura did preserve the wetland and convinced a company not to leave Brooklyn Park, but was unable to reduce taxes and spent his last year in office batting at a residency scandal. During his tenure Mayor Ventura had purchased a house in Maple Grove, one better suited to his wife Terry’s equestrianism. Pressed on the issue by his opponents and media, Jesse answered, “I haven’t stopped the garbage service [at his Brooklyn Park residence]. I sleep there—sometimes. I mean, not to sound like a slut but I sleep around a lot.”

After leaving local office, Ventura did not lose interest in politics. He quickly aligned himself with the Minnesota Independence Party, an outgrowth of Ross Perot’s first presidential campaign in 1992. Four years later, the IP was absorbed into Perot’s new national Reform Party, a hodgepodge of disparate political elements united around austerity and anti-corruption. Perot, who, it’s widely accepted, rigged the 1996 Reform nomination in his favor and failed to build on his previous 19% of the vote, did little to develop state Reform Parties in the ensuing years. Instead it was Independence Party co-founder Dean Barkley who courted Jesse and his family, beginning Ventura’s ring-walk into the Minnesota-wide electoral arena in 1998.

Then and now, Ventura’s election is often dismissed as a strange accident, the political equivalent of the Vikings’s surprise 13-win 2022 season. But this belies the campaign’s tactical shrewdness in beating Republican Norm Coleman, a then-popular St. Paul mayor, and Democrat Skip Humphrey, son of an iconic U.S. vice president.

Ventura didn’t enter the race until the day of the deadline in July 1998, freely admitting he wanted to keep his sports-talk broadcasting gig as long as possible. (“What am I gonna do if I actually win this thing?” Ventura asked a KFAN producer before the election, per Sports Illustrated.) It was this kind of candor that broke through voter fatigue and gave the new campaign hours of earned media. In a move George W. Bush would emulate in 2000, Ventura balanced his libertarian economic views with an emphasis on education, selecting Mae Schunk, a public school teacher, as his running mate.

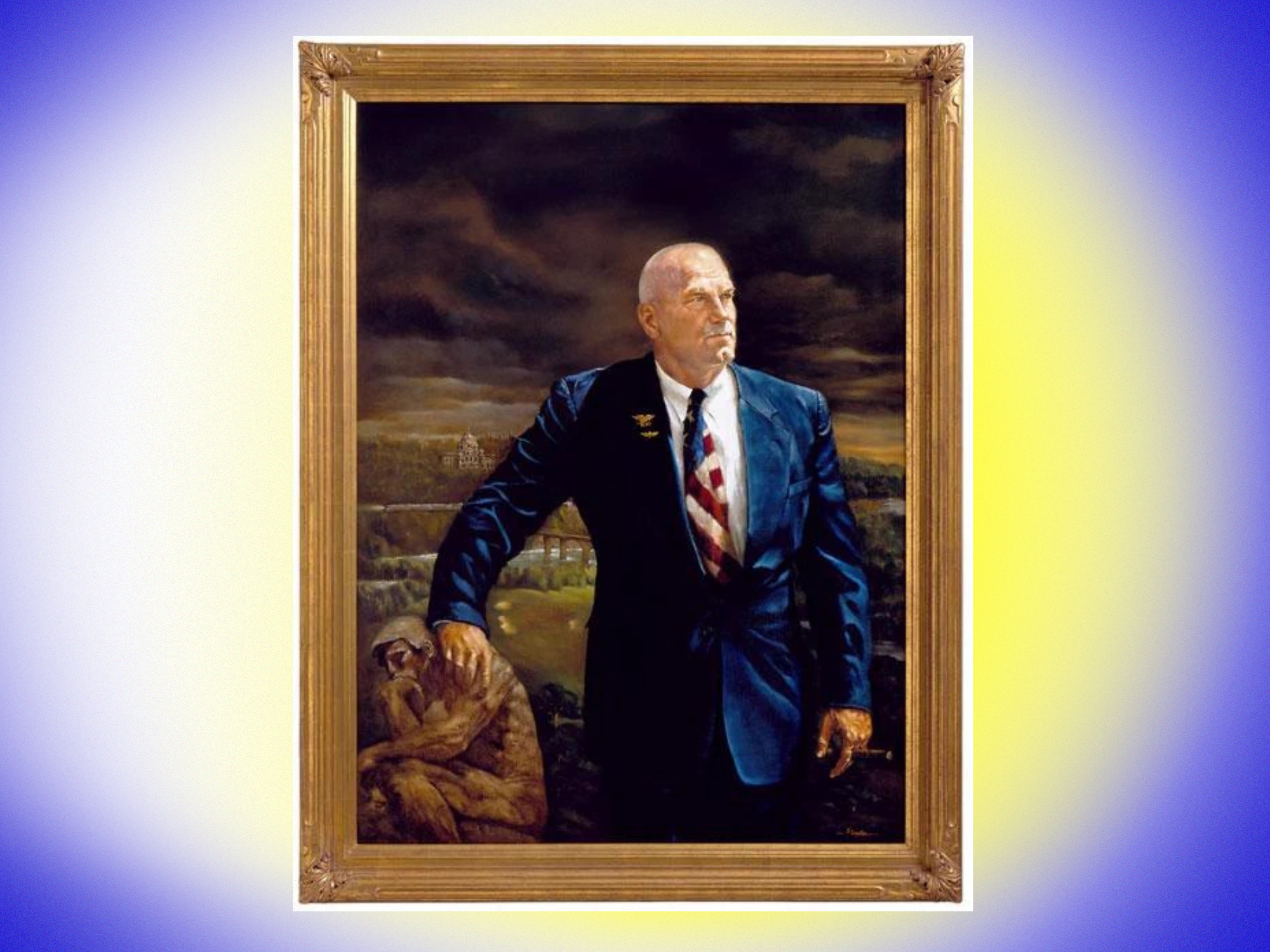

Ventura also toned down his eccentric style with a shaved head, prominent mustache and suits that, thanks to a fatal error by the Humphrey campaign, Jesse got ample opportunity to wear in the debates. Figuring that Ventura’s anti-government rhetoric would draw votes away from Coleman, Humphrey insisted on Jesse’s inclusion in a series of televised debates. But Humphrey went from the top of the polls to 28% of the vote on election day, behind Coleman’s 34% and Ventura’s 37%. Eager to attract his supporters, the Republican and DFL candidates forgot to attack Ventura and the chorus of “I agree with Jesse”s only redounded to the wrestler’s benefit. The Reform campaign was also buoyed by Minnesota’s same-day registration rule, which let thousands of first-time voters, untracked by the polls, in on the fun.

Gov. Ventura took office on January 4, 1999, in a respectful ceremony at the state Capitol, flanked by buddies from the Navy SEALs. This was soon followed by a raucous celebration at Target Center in downtown Minneapolis. Around 20,000 Minnesotans gathered to watch their new governor rock out in a Vikings-colored feather boa, fringe jacket, and sunglasses, with help from "Kid" Johnny Lang and Warren Zevon, the latter of whom played his top hit as Ventura sang a rendition, “Werewolves of Minnesota.” The next day the governor took great offense, at his first press conference, when teased about his imperfect singing. A rocky, four-year relationship with the Minnesota press corps had begun. Within weeks, the extemporaneous speaking style that elected Ventura was embroiling him in controversy with tribal citizens, unwed mothers and, of course, St. Paul residents of Irish extraction. It’s hard to blame reporters for covering the spectacle, but Ventura argued that the bad press overshadowed his gubernatorial accomplishments.

Ventura approached the appointment process free from partisan attachments, instead hiring a professional headhunter to fill state agencies and commissions on the basis of competence. Despite an early hiccup at DNR, the Ventura administration was widely praised for its personnel. Even Jesse’s former opponent Skip Humphrey told the governor at an event, “This is the best cabinet in the United States.” In the late '90s, one of Minnesota’s prime political debates was over what to do with the state’s multibillion dollar budget surplus. Ventura’s prerogative was a rebate for taxpayers which, after prolonged negotiations with the legislature, came in the form of $700 “Jesse Checks” each summer of the governor’s four year term. Ventura’s libertarian views proved to be flexible, however, when it came to expenditures like light rail transit, for which the governor enthusiastically advocated and nudged through a GOP-majority state House.

Another issue Ventura used his platform to promote was free trade, a hot-button topic during the Clinton era. As governor, Jesse went on trade missions to Mexico, secured a pork market for a Minnesota farming cooperative in Japan, and displeased the Bush administration by traveling to Cuba to discuss lifting the U.S trade embargo with President Fidel Castro. Somewhat odd in retrospect, given Ventura’s current anti-corporate sentiment, the governor also testified before Congress about normalizing trade relations with China on terms largely determined by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. His position on trade policy put him at odds with the national Reform Party, which embraced Ross Perot’s steadfast opposition to NAFTA and other big-business-friendly trade deals. The tension came to a head in 2000, when nationalism, economic and otherwise, came to dominate the Reform Party.

In early 2000, Gov. Ventura backed Donald Trump’s exploration of a Reform Presidential run, hosting the real estate mogul in Minnesota for a press conference. Trump had pitted himself against the Reform Party frontrunner Pat Buchanan, calling him a “Hitler lover” in reference to Buchanan’s long history of xenophobia. When it became clear that Buchanan was running away with the Reform nomination, Trump bowed out of the race. On February 11, 2000, Gov. Ventura announced, in a leather Rolling Stones jacket, that he and Lt. Gov. Schunk were disaffiliating from the national Reform Party. The state party immediately followed suit, returning to its original and current form, the Minnesota Independence Party. As its sole elected official, Ventura would have been a logical choice as the Reform Party’s presidential nominee. And with the 2000 election so close, who knows what kind of impact he would have made? But the governor demurred, insisting that he complete the job he was elected to.

With a Republican House and DFL Senate, the Ventura years gave Minnesota a tripartisan state government. If there’s one thing that united legislators from the two main parties, it would be stern disapproval of Gov. Ventura’s personal conduct. In August 1999, he was condemned by Republican and DFL leaders for refereeing a pay-per-view World Wrestling Foundation “SummerSlam” match. (in Jesse’s defense, it was on his “night off.”) Given Ventura's private-sector earnings, legislators neglected to raise the governor’s pay despite doing so for themselves and Lt. Gov. Schenk. This gave Gov. Ventura the perfect excuse to pick up another gig in 2001, this time with the upstart XFL football league.

Ventura’s various off-the-cuff remarks stirred constant controversy as well. In a 1999 interview with Playboy, the governor declared organized religion to be a “crutch for weak-minded people” and, when asked what fabric he would like to be reincarnated as, answered “38 double-D bra.” While Ventura’s popularity took a serious hit from the Playboy remarks, by 2001 he had somehow managed to bring his approval rating back up over 70%.

Often lost in the bombast was Ventura’s capacity to make amends. As noted by Ken Peterson, who served as deputy attorney general during the Ventura years, the governor’s inappropriate statements could become opportunities for growth. After angering members of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe by questioning their claim to fishing rights, Ventura went on to educate himself on tribal sovereignty through extensive tutorials and visits with tribal officials. According to Peterson, his administration oversaw “updated tax agreements with tribes, public safety pacts between tribal, county and state governments and a first-ever executive order recognizing the equal nature of state government and tribal government interactions,” winning praise from tribal presidents like Prairie Island’s Audrey Bennett. Gestures like these, as well as new millennium era economic stability, made Ventura a popular governor. But that high regard wouldn’t last forever.

Ventura did himself few favors with his propensity for petty feuding, a habit from his wrestling days he was unable to shake in politics. In 2001, he made headlines for defending his DNR commissioner in a heated meeting with Star Tribune outdoors columnist Dennis Anderson, whose hunting expertise the governor questioned on the basis of Anderson having never “hunted a man.” That same year, the Capitol press corps received new credentials from Ventura’s office bearing the title “Official Jackal.” Some journalists were amused, but outlets like Minnesota Public Radio, which instructed its reporters to refuse the passes, failed to see the humor, something Jesse could be guilty of when the joke was at his expense. In 1999, Garrison Keillor, MPR’s sleepy yet then-popular main attraction, wrote a satirical book about “Jimmy (Big Boy) Valente,” a fictionalized version of his new governor, portrayed as dim and self-centered. The real-life Ventura responded with a proposal to cut public funding for MPR and, in an interview with former Clinton Chief of Staff/future U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta, stated “Garrison Keillor couldn’t hold my jock strap.”

Jesse also held an open grudge against Sen. Paul Wellstone who, he claimed, resented Ventura’s 1998 victory because Wellstone's son worked on the Humphrey campaign. The pair’s real dispute may have stemmed from their contrary sides of the wrestling discipline. Wellstone, a college wrestler, distinguished himself as a patron of “real wrestling” which Jesse often made a point to refer to as “amateur.” Nevertheless, Gov. Ventura maintained a statesman’s composure after Wellstone’s tragic death shortly before the 2002 midterms, and even committed to appoint a DFL replacement. However, the governor took such umbrage at the politicized nature of Paul and Sheila Wellstone’s memorial service (an odd complaint given how they led their lives) that he reneged on his promise and appointed the Independence Party’s Dean Barkley instead.

By his last year in office, Ventura’s approval rating had fallen to 43%. He spent his final months as executive in a fight over the Governor’s Mansion, whose staff Jesse fired after they told reporters that his son, Tyrel, was throwing raucous parties at the official residence. Gov. Ventura, who had moved with Terri back into their home in Maple Grove, vehemently denied the allegations and took the opportunity to propose defunding the mansion given the state’s new deficit woes. (The Summit Avenue estate is currently undergoing a $6.3 million renovation.)

The post-9/11 recession left state governments across the country with less revenue and Minnesota was no exception. Having announced that he would not seek a second term, Ventura pivoted to full austerity mode and tried to initiate both spending cuts and tax increases to address a budget shortfall. By then, his relationship with the legislature was too damaged for the plan to gain serious consideration. Not helping matters: the permanent basis by which Ventura and the legislature had enshrined tax cuts a few years earlier. Republicans and the DFL were happy to let Gov. Ventura absorb the blame. Ventura's legacy would become synonymous with the $4.5 billion deficit he left office with. In 2002, the stage was set for conservative Republican Tim Pawlenty, who successfully branded himself as a fiscal disciplinarian, despite eventually leaving Minnesota with an even larger deficit than Ventura.

Ventura is remembered fondly by many policy wonks for his judicial and cabinet appointments, including Health Commissioner Jan Malcolm, who set up an anti-smoking endowment with tobacco settlement funds and, decades later, led Minnesota’s DOH through the COVID-19 pandemic. As governor, Jesse also increased education funding by decoupling it from property taxes and streamlined state computer systems through the new Information Resources Department.

Ventura’s greatest impact, though, may be the agenda items he introduced to the public but didn’t get to enact. In addition to passing light rail, which didn’t begin service until 2004, Gov. Ventura advocated statewide broadband, ending the war on drugs, publicly funded elections, legal gay marriage, and a unicameral legislature. That last proposal would have combined the State House and Senate into one legislative body. Minnesotans overwhelmingly wanted a referendum to decide the question, which several officials from the two major parties supported as well—publicly, anyway. To Gov. Ventura’s great frustration, the referendum legislation died in committee.

Positions like the single-house legislature have earned Jesse Ventura the “populist” moniker which, especially over the past decade, doesn’t always have positive connotations. Celebrities running for public office, pundits warn us, denigrate the political process by making a mockery of “experience,” eliding substance and drowning out experts with popular but reactionary ideas. The most egregious example of this is, of course, Ventura’s erstwhile ally, President Donald Trump who, some argue, Jesse laid the groundwork for. When you zoom out, however, the celebrity politician group portrait is more complex. Trump may sit firmly on the right, alongside the likes of former Carmel, California, Mayor Clint Eastwood. But there’s also a vibrant center, occupied by Ventura’s Predator co-star Arnold Schwarzenegger and, arguably, ex-actor/current Ukrainian President Vlodymyr Zelensky; as well as a sizable left, made up of people like one-time New York gubernatorial candidate Cynthia Nixon and Minnesota’s own Al Franken.

With his heterodox hodgepodge of often contradictory views, Ventura is probably the celebrity politician who reflects American opinion best. Just as there is nothing inherently radical about third parties, there is nothing inherently reactionary about entertainers running for office. As Jesse Ventura proves, they can and should be judged on the merits, just like any other old governor of Minnesota.

Additional sources:

- "Running a Three-Party Government," C-SPAN

- "Third Party Candidates," C-SPAN

- "Minnesota's Governor Is Hitting a Rough Spot," New York Times

- "The political legacy of Jesse Ventura," Minnesota Public Radio