It’s understandable if you walked out of director Denis Villeneuve’s first Dune film in 2021 thinking you’d just watched the start of the same old hero’s journey you’d seen in so many movies before. Like Luke Skywalker or Harry Potter, Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) is a cute young guy discovering the extent of his mystical abilities, which will place him at the center of a massive conflict between good and evil. Yawn.

Maybe you knew that the film’s source material consciously undermined the mythology of the noble chosen savior. Yet side from some catastrophic visions of the future that trouble Paul, there was little in Dune to suggest that Villeneuve shared author Frank Herbert’s obsession with the moral consequences of exercising political power, or that his sequel would attempt more than a superficial exploration of the novel’s complicated interplay between colonial resource extraction, religious fundamentalism, and prophetic realpolitik.

And, like, I get it. The guy’s making movies, after all. You’re there to see giant worms emerge out of the desert floor and gobble people up, to watch Timmy and Zendaya make googly blue-within-blue eyes at each other, not to study for your PoliSci exam. But here’s the Dune paradox: The more strictly you hew to the mere plot, the duller it is. And so, as I wrote here, the first part of Villeneuve’s adaptation was a well-crafted slog, occasionally spectacular but often merely studently, as Villeneuve seemed intent to prove that he deserved the assignment. (Ornithopters! Glowglobes! Ooh, Holtzman shields that don’t look like Atari 2600 graphics!) Because if anything is interesting about Dune (and I admit that’s a debatable if) it’s not what the characters do, but why they do it. Otherwise, you’re just moving chess pieces with funny names around a board made entirely of sand.

And so the only proper response to hearing Florence Pugh’s throaty alto drone on about the events of the first film at the start of Dune: Part Two is a hearty “Hell yeah! It’s time for some space politics, baby!” Pugh is Princess Irulan, daughter of the Padishah Emperor (Christopher Walken, who somehow looks even more like himself the older he gets). Stone-faced and analytical, Pugh’s intermittent narrator is clad in a sort of Joan of Arc chainmail getup at all times. We’ve never seen or heard her before, and her appearance at the start places us immediately on notice that though Paul may be the central figure of this saga, the boundaries of power in Dune are set by women of far-reaching vision.

Among these women is Paul’s mother, Jessica, and in this sequel Rebecca Ferguson comes into her devious own. While her role in the first installment could be summed up with the recurring closed-caption notation “[Lady Jessica whimpering],” that changes now that she and her son are in hiding. Her husband the Duke (Oscar Isaac) is dead, murdered along with most of his people by his rivals, the evil, bald, pallid Harkonnen family, who once more control the desert world of Arrakis and can mine its invaluable spice, a substance that every other planet relies upon to travel through space.

But in exile, Jessica assumes a powerful role among the Fremen, the people of the desert, as she conspires with her in utero daughter to convince them that Paul is their messiah. Jessica, like most of the women pulling the strings here (including Irulan), belongs to the Bene Gesserit, an order of witchy puppeteers who, like gender-flipped space Jesuits, exercise power behind the scenes. Paul is their creation, his mystical gifts the result of centuries of selective breeding, and the prophecies about him are Bene Gesserit-generated as well, seeded into Fremen culture for the order’s future use.

Whew.

OK, I know that can read like a whole mess of exhausting nonsense. And trust, Dune: Part Two is indeed as humorless as it is ambitious—with a single snicker of disbelief you can bring its epic pretensions crashing down like a sun-baked sandcastle. Unlike its predecessor, though, there’s some pay-off to your emotional and even intellectual investment. As Paul’s exposure to spice hones his visionary gifts, he becomes acutely aware of the immense suffering a wrong decision on his part can bring about, and seeks to balance his duty to those he loves with his struggle to prevent his apocalyptic visions from becoming reality. And that’s a quest that Villeneuve, hoping to mine IP with more dignity and respect than the Harkonnens of the MCU and other lesser corporate pirates, certainly identifies with.

Dune: Part Two does an awful lot right. As written, with characters mentally questioning the meaning and intent of what others say aloud, Herbert’s Dune is no more filmable than late Henry James. But Villeneuve distills the essence of the novel’s currents of deception and misdirection. Paul works to determine how much he can trust his mother, given her divided loyalties to him and to her order, even as he tries to convince his Fremen lover, Chani (Zendaya), who’s rightly skeptical of how the otherworlders are using fundamentalism to exploit her people, that she can have (secular) faith in him.

The sequel pares away a greater deal of Dune lore than the first half did. Gone is Atreides aide Stephen McKinley Henderson’s Thufir Hawat, so if you never bothered to figure out what a mentat is, don’t worry, you’ll be fine. (You didn’t really want to sit through a lecture about the Butlerian Jihad, did you?) And Villeneuve ably streamlines the crosses and doublecrosses of the book’s latter half into a more sleekly coherent arc, even if there are some sacrifices: Paul’s sister Alia is not born before the final battle, so anyone who’d hoped to watch a four-year-old girl run around stabbing soldiers is sadly out of luck. So is anyone who (foolishly) thought they’d see a major studio movie in 2024 that didn’t have Anya Taylor-Joy in it. (She appears briefly as a vision of the adult Alia.)

Speaking of people who seem to get cast in every damn movie these days, my biggest concern with Dune: Part Two was whether the perpetually callow Chalamet, who has seemed as incapable of gravitas as he is of a full mustache, could grow into the role of a messianic desert warlord. And not just for the sake of Dune—the guy’s not going anywhere, and we’re all better off if he expands his range beyond jerky kids with sexy hair. For the most part, he does, showing us a man who makes a pragmatic decision to exploit the dogmatism of his followers because he believes that every other choice will cause more death and destruction, or who at least rationalizes his motives that way. By the end of the film Paul has become an intriguing composite of bluster and doubt.

Even more rewardingly, Villeneuve finally generates some truly uncanny moments in this film. The scenes on the Harkonnen home planet Giedi Prime, where a black sun casts everything in a photonegative colorlessness, make for a grim spectacle, as fireworks splatter across the sky like inkblots and pasty hordes cheer for rigged gladiatorial spectacles. Here Villeneuve strips the fascist aesthetic of its cinematic appeal to reveal the petty bloodlust at its core.

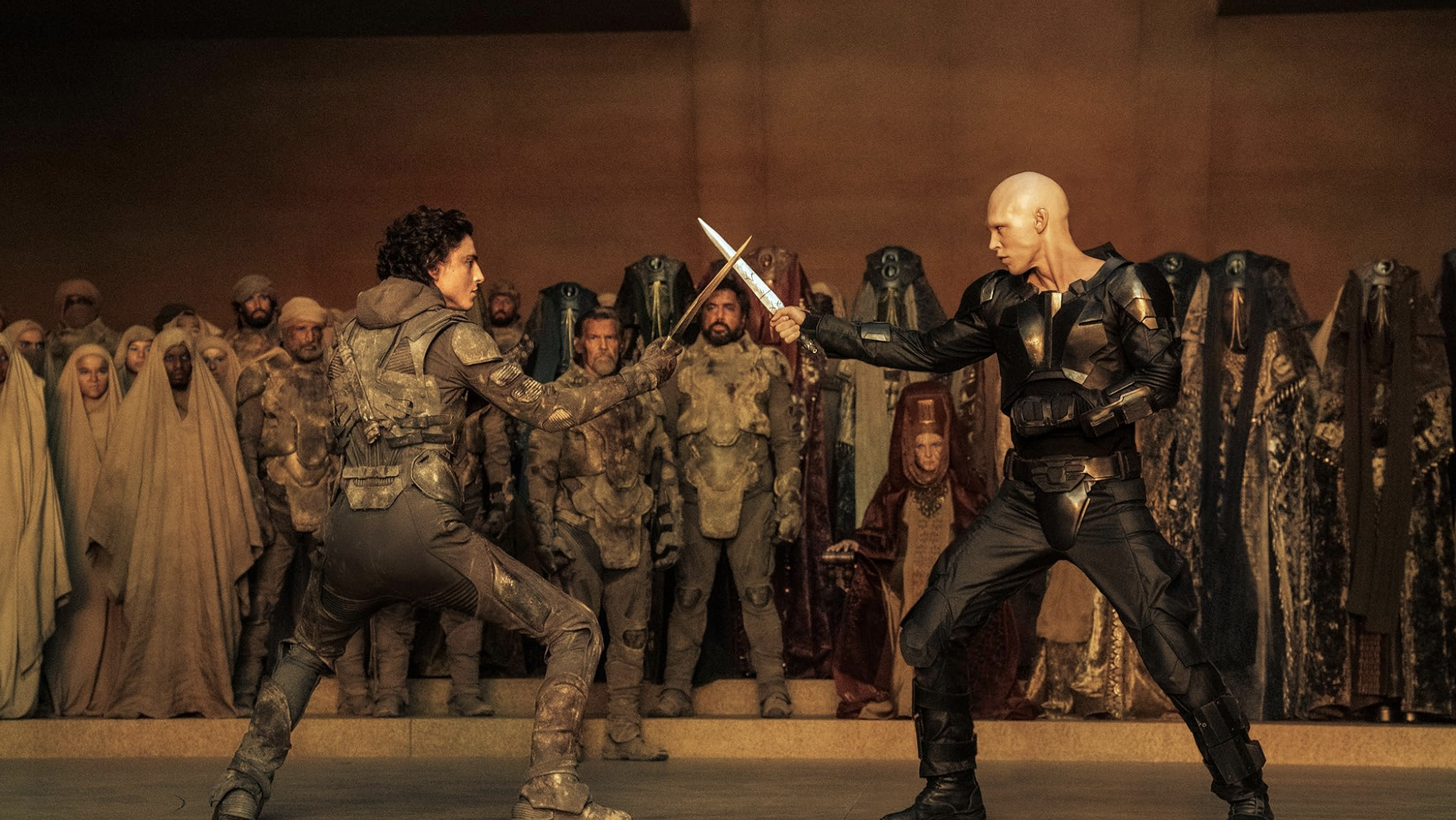

The baddies who dwell on that world—Stellan Skarsgård’s bloated Baron Harkonnen and Dave Bautista’s cowardly and impulsive Beast Rabban—are joined this time around by their dynasty’s great white hope, a blade-happy freak named Feyd-Rautha. He’s played as a masterpiece of clammy prosthetics and disturbingly incongruous tics by Austin Butler, and when he channels Skarsgård’s gravelly tones he comes off like Froggy from The Little Rascals.

Feyd-Rautha also happens to be a Bene Gesserit asset, and Léa Seydoux has a brief, terrific turn as his handler. Hers is among some well-executed supporting parts. As the Fremen leader Stilgar, Javier Bardem (one of the few actors who seems to be enjoying himself here) slips slowly yet decisively from comradeship into committed fanaticism. Saggy and stooped, Walken’s aloof Emperor embodies a dying regime that keeps itself intact by overplaying its hand.

On the “eh” side we have the return of Josh Brolin’s Gurney Halleck, still less a character than a series of variations on “grizzled.” (Though we do finally get to see him bust out his lute.) And Zendaya—well, she’s fine, but Villeneuve places more of the film’s emotional burden on her shoulders than she can bear. Though she and Chalamet do have chemistry, the squint ‘n’ furrow of her fierceness still has too much Disney channel attitude to it.

And in general, Villeneuve still errs on the side of faux-realism when we could use a little more make believe. Too often, action sequences are cloaked in dust clouds, which, yes, I suppose would happen in a desert, but this is not really happening, so you can make it look however you want. No doubt Villeneuve is haunted by the garish pop grotesquerie of David Lynch’s doomed 1984 adaptation, but for all its flaws, that strange creation remains visually memorable in a way Villeneuve’s rarely does. There’s a reason “Villeneuvean” is not yet an adjective. (That said, a grisly scene with ants crawling into an ear here has got to be a nod to Blue Velvet, right?)

And even if Villeneuve’s not going to be David Lynch about things, there’s no reason he can’t at least be David Lean. Sometimes the camera closes in on a scene when you wish it would pull back for a more cinematic sweep, especially when Paul finally rides atop a mega-sandworm. And while the Fremen attack technique of rising from below the sand to ambush their foes is consistently awesome, too often Villeneuve’s idea of a battle sequence is to have a bunch of soldiers run into a bunch of other soldiers. It’s like he’s afraid of making his movie look too much like a movie.

Dune’s real-world referents must have felt like one-to-one parallels when the novel was published in 1965, with spice a mystical variation on oil and the Fremen as Arabs sussing out their relationship with the First World powers. Maybe the most significant change Villeneuve has made is to excise much of the Arab-ness from Herbert’s conception of Fremen culture. The word “jihad” has given way to the more generic “holy war”—probably for reasons of “sensitivity,” but effectively a kind of whitewashing—while their language in general has been stripped of Arabic roots for more pedantic lexicological reasons.

Then again, Herbert’s preoccupations have since been refracted through a half-century of history, revealing instance after instance of failed foresight from the secular prophets who serve as architects of political power. (Paul could be the U.S. arming the mujahideen to resist the Soviets—and we all know how well that played out.) The hard colonialism that was in retreat after World War II was reasserted through “softer” financial extortion, and fundamentalism is no longer some exotic strain of religion but an emergent force that seeks control right here in the homeland. You can’t tell this story exactly the same way now—especially with real Arab corpses appearing in your news feed daily.

Though both the Dune films and the novels toy with fatalism they can never reject out of hand, it’s hard to determine how thoroughly Villeneuve’s politics overlap with Herbert’s. As the films tell his story, Paul (aka Usil, aka Muad'dib, aka the Mahdi, aka the Lisan al Gaib, aka the Kwisatz Haderach—dude has more names than Ray Jay Johnson Jr.) is a man with no good choices, looking for the least worst route through history. And his solution may be a more flexible colonialism. Sometimes an empire’s gotta do what an empire’s gotta do, after all, and once powerful outsiders tinker with an indigenous culture, Dune: Part Two suggests, the only way out is through.

And maybe spice is something more than fossil fuels these days. When an unknown voice rumbles, “He who controls the spice controls the universe” in an unknown tongue to begin Dune: Part Two, certain other less tangible sources of wealth and power that have risen in value since 1965 come to mind. Among those, yes, is intellectual property, and you can’t address the politics of Dune: Part Two without acknowledging the politics of commercial art. Especially at a moment where we can understand why Herbert’s imaginary civilization banned computers as heretical devices. (If I can speak strictly to my Dune-heads for a second, most filmmakers are just duplicitous Bene Tleilax fashioning ghola from the corpses of dead IP, amirite?)

With IP-recycling now the culture industry’s standard cannibalistic practice, Villeneuve, like Paul, imagines himself the good guy in this scenario, respectful of the traditions placed in his care rather than merely exploitative. But also like Paul there are forces at play beyond his control. So what happens when Villeneuve’s hero threatens to become a butcher?

It’s hard to read any final, fixed meaning into all this because of course Dune: Part Two isn’t the end. A third film is yet to come, and if it tracks closely with Herbert’s own sequel, Dune Messiah, we have some downright freaky shit to look forward to. Dune: Part Two left me wanting more in a way Dune hadn’t, and I can see Villeneuve extracting an emotionally satisfying (if far from happy) ending from the source material. Then again, as Herbert constantly reminded us, our visions of the future are not always accurate.

GRADE: B+

Dune: Part Two is now showing is area theaters.