Stepping into the Cedar Cultural Center after Drone Not Drones has begun is like becoming Alice, walking through the looking glass. It’s another world. Dark. Meditative. Reverential.

But instead of dapper rabbits and zonked caterpillars, hundreds of people lie on the floor nestled under blankets. Some are even asleep for the night.

Originally conceived by founder Luke Heiken as a protest against Obama-era drone warfare, Drone Not Drones, a concert and benefit for Doctors Without Borders, will host its 10th installment on January 24. Born out of a 2013 Rock the Garden set from Low, it has become a reliable muster of the—for lack of a more accurate and encompassing term—experimental music community.

The 28-hour marathon features more than 60 performers who continue a drone without interruption, passing a sonic baton between overlapping sets that, briefly, necessitate an improvised collaboration.

More than a dozen performers, organizers, and listeners have shared their stories of how the event came together and became an annual gathering place for venturesome performers and listeners.

“These Drones Are Bullshit. That’s All I Gotta Know.”

Luke Heiken, founder of Drone Not Drones: I was playing with a sticker maker, listening to drone. I forget exactly why I made one, but I made one that said “drone not drones.” It came to me based on just the play on “blank out of blank” or “blank, not blank,” just one of those bumper sticker cliches.

Then that night or something, because the sticker was sitting next to me on the couch, I pulled up Twitter, which even in its heyday I didn't look at a lot, but I just happened to pull it up that day. Alan Sparhawk had posted, “Mim says, fuck drones.” And then I sent him a picture of the sticker and he might've retweeted it.

Alan Sparhawk, musician/Low: I knew Luke, and I think he sent me a bumper sticker.

Heiken: The original thought was to do a benefit drone compilation album, and that's how I was going to raise money for Doctors Without Borders. Maybe the compilation would've happened, maybe it would've petered out. Who’s to say? I get a lot more ideas than necessarily results in my life.

So, I was not at Rock the Garden in 2013. Especially now, I wish I would've gone.

Sparhawk: I remember when we did that show, there was a certain series of events that happened that day that just kind of tipped it to where we ended up being like, ‘Well, let's just play this one song.’ Our set had gotten shortened. There's weather problems and stuff like that.

There was some stuff that had come out recently about the U.S. using drones. It was just another flex of imperialism. So, we did that piece and it felt like, just to me, it felt the whole time we were doing it had a weight to it. I don’t know, Luke’s slogan just came to mind, and I said it at the end.

Heiken: All of a sudden I started getting texts.

Sparhawk: It wasn’t planned necessarily. It was just what I was feeling in the moment.

Heiken: I had posted the phrase before. So, people kind of knew to text me.

Sparhawk: I think possibly because we had played this piece and it was just this drone thing, it kind of divided the audience a little bit. Some people perceived the show as some sort of protest that we did, some sort of whatever. But we were just trying to do something cool. I'm not going to waste a platform and not say what I felt needed to be said.

Heiken: The Walker wanted to do a story right away when they heard it had to do with something and he was quoting that. They wanted to interview me for this thing. So, all of a sudden, people are talking. It's kind of a local meme at that point.

Philip Bither, Walker Art Center’s senior curator of performing arts, writing on the Walker’s website: I guess the kind of riots that erupted in Paris after Stravinsky’s premiere of The Rite of Spring in 1913 now happen online.

Heiken: Getting into late summer, the compilation thing was still happening, but that kind of stuff is very slow moving and I'm like, “Hey, this is like a moment.” I need to—I wish there was a better word to use than capitalize on it—but to do something with it because it's ultimately to raise money for Doctors Without Borders. So, then I had the idea for the concert.

I kind of started to find theaters and no one was biting. But when I approached the Cedar, they were all about it. They were all in from the beginning. They got it.

Caleigh Souhan, senior events manager at The Cedar Cultural Center since 2021: They have just been the most magical events.

Heiken: So, 28 hours was partly because people were complaining about Low doing a 28-minute drone. I was always like, 28 minutes? Shit. I want a 28-hour drone.

Part of it was that. Part of it was, 28 hours is the perfect time. If you start a show at 7 p.m. the first night, you don't want it to get done at 7 p.m. the next night. That's too early for something to be done.

Liz Draper, bassist/portal iii/Chama Devora: It's like a grownup sleepover.

Heiken: The concert itself was inspired by a couple things. There was one that was done up in Duluth as a benefit.

Sparhawk: Up in Duluth, we did a continuous drone, 25-hour drone, one time. It was right after 9/11, actually. It was kind of a little collective. We did this weekly Tuesday experimental event stage, and there had been a little bit of a scene building around that.

Heiken: I was inspired by that and by how much fun I had at one of Mark Mallman's marathons. It was those two things, I think, even if I didn't know it at the time.

The First Year, “Rules,” and Beyond

Luke Heiken, founder of Drone Not Drones: The first band was Prairie Fire Lady Choir.

Lisa Heyman, Prairie Fire Choir: Valerie Kahler wrote the arrangement for us based on the Crosby Stills, Nash, and Young song "Find the Cost of Freedom.”

Heiken: The recording is on Bandcamp, and people actually clapped when they were done and I was like, “Oh, God, I don't want people to clap.” But I didn't want to be like, “No clapping!”

Alex Bissen, IOSIS/stage manager and creative partner for Drone Not Drones: It's really not a series of performances. It is one performance, and you stick around for any duration until the end.

Liz Draper, bassist/portal iii/Chama Devora: It's an all-night experience to just become fully immersed in, if you can and want to, and you'll hear really interesting diverse takes of what it means to even create a continuous drone.

Elaine Evans, founding member of International Novelty Gamelan/multi-instrumental performer: The continuous thing reduces the social time because a lot of times, going out to music shows, there are people who, they really like to talk during the breaks. For some people, they're into music, but they're going to see their friends.

Scott Brown, Noise Quean Ant: A definition of drone is subject to a wide variety of interpretations, and what makes something a drone to one person is not necessarily what makes it for another person. It's a state of mind. And, I am sorry, what was the question? [Laughs.]

Paul Metzger, banjoist: It doesn't have the same baggage as the blues as a form because it really can go anywhere. So, I have a very open idea of what drone music is, and so do most of the people that I've been lucky enough to hear at the thing.

Brown: I mean, it's based on repetition to the point of confusion for me.

Benjamin Polk, Old Moon: I’m really interested in the way drone can disrupt our perception of time and how that can maybe interrupt, let’s say, capitalist modes of domination.

Jon Mueller, percussionist: I knew that people going to this were focused on listening. Certainly, there's a social element to everything when there're people in a room, but I knew that the focus was really on this sort of long-form listening. That has a built-in idealism to me, because you're presenting your work in a scenario where it's not about you. It's about being part of this experience where people are engaged in the process of listening.

Bissen: There's only one round of applause, and when it hits, if you've been there for a while, when that hits, it's just so weird. It's just like, “Oh yeah, this is the end of this performance.”

Alan Sparhawk, musician/Low: I think there's a certain relief in knowing that you're part of the background in some ways. You know what I mean?

Metzger: I like that invisibility when there's so much of a focus on, I don't know much about it, but there's so much a focus on wanting to be somebody. For me, that's never been an attractive pursuit.

Bissen: While I don't think it was called “the drone” from the beginning, it was, speaking for Luke here, I think as he envisioned it, it is one thing very intentionally, very fundamentally, it's one thing. It is the 28-hour drone.

Heiken: Then after the second band, people kind of stop clapping. That made the precedent to not clap. So, it almost turned into a clapping thing.

Metzger: I love the lack of applause. I don't want to hear that anyway.

Bissen: We have two rules for the performers. I mean, it really is this simple. Don't stop. Hard rule. Do not stop, ever, for any reason. We had a performer, Alone-A, last year. The power went out. Don’t stop. She knows the rules, man.

Caleigh Souhan, senior events manager at The Cedar Cultural Center since 2021: She worked for The Cedar before.

Bissen: I was watching and she flustered for just a moment and then she fucking went.

[Alone-A sang a cappella until the power came back.]

Heiken: It was perfect that it was her. She knew what to do.

Souhan: It was just a weird little fluke, but we're all so grateful that she was actually able to not allow it to stop.

Metzger: I'm pretty reclusive, but whenever I see Luke, I'm happy to see him and I want to hug him. I think what he's doing is—I have this outlook on being a musician in this area of creativity that's kind of off the beaten track. It's not mainstream. You're doing some shit that most people wouldn't want to be around. I call that kind of pursuit ridiculous, in a way, because you're doing it in spite of the pragmatic concerns of trying to be alive on the planet in a capitalist nation.

Heiken: I used to not want the drone to stop at all. I just kind of had to let it go. The first time there was something, it was like, “Oh no.” You could feel the energy in the room when it went silent, like, “Oh no, you're not supposed to do that.”

Bissen: We've had one person in nine drones that did not get that. He gets up there and plays for, I don't know, five minutes or something, then stops. Starts another song. When he stopped, you can hear people fucking gasping.

Heiken: To me now, that silence is just, it's being framed by the drone before and after it. It's part of it. But when it first started, I was more like, I want it to be like this continuous sound. As long as it's silences within the dynamics of a song. I don't want silences where it's just in between songs that you're playing.

Metzger: This particular thing that Luke wanted to do is equally ridiculous. I want to take a whole bunch of musicians and have them continue a drone idea for 28 hours? I mean, the amount of work and caring about it is pretty huge. It's as ridiculous as anything, and I really love that type of pursuit.

Bissen: There’s that crossover where one band, one act is handing off to the other. If there is a third rule, I tell people to relish that. Spend some time in there, man. That's where the real cool shit happens.

Heiken: Crossovers are where the magic happens. That's our secret sauce or whatever. I think that's where the magic is. I think that's kind of the je ne sais quoi.

Sparhawk: Those are my favorite. Sometimes it's really exciting. Sometimes it's terrifying. Going after Joe Rainey in 2024 was personally just really heavy and intense for me. It really made me stop and sort of have to check myself. Well, I am nothing at the feet of this amazing person. I feel the weight of what he's speaking of, and I feel the weight of my own history and my own ancestors, and the fact that I exist on the suffering of something that this person is addressing right now. How do you follow—how do you interweave with that, much less follow it?

Joe Rainey, powwow singer/Bizhiki: We've done that before, but he's so respectful. Alan's such a humble dude. Just having conversations with Alan the number of times that I've had, he's always just very thankful to Indigenous music, Indigenous artists. He's always willing to learn more, but he's also wanting to shine a light.

Laraaji, musician: You relate to it or you relate within it. I like that idea. That's the way life is, too. You hear an ambulance siren and then you hear a mother and daughter talking as they're walking down the street in front of you. All kinds of sonic intentions can overlap in the city, especially, and in life. There's a license. If you're a sound and you want to happen, there's nothing that says you're out of place in life.

Heiken: From the beginning, I had hoped it'd go well enough where maybe we could do it every year. Because, at that point, Heliotrope was every year, and that was one of my favorite things every year.

Bissen: Put that in the list of places where Luke got lucky. [Laughs] He figured out the show’s structure the first year, and it really hasn’t changed. I think the only real difference is, the first year, there was a march down Cedar Ave. This thing started as a very clear anti-war statement.

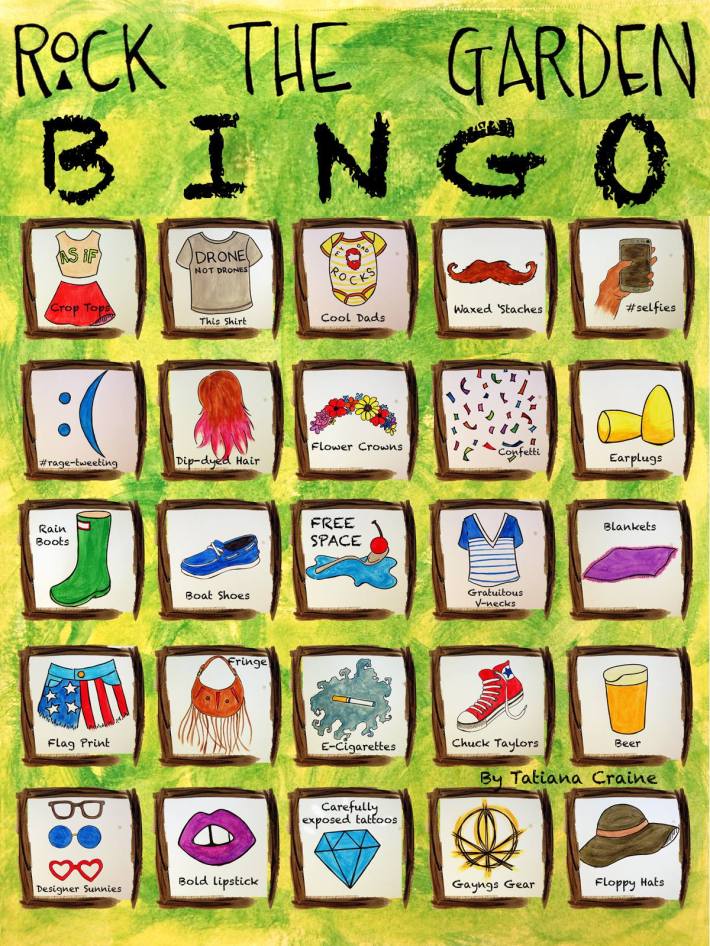

Luke Heiken: That next summer, for Rock the Garden, City Pages made a Rock the Garden bingo card, and one space was spot a Drone Not Drones shirt.

And City Pages put Low on the cover for something or other, and they wanted Alan to wear a Drone Not Drones shirt. So, it was on the cover of City Pages. Two different people wore it on late-night TV performances. Then somebody gave one to the drummer from Grateful Dead, Mickey Hart. He wears it all the time.

Will Oldham, musician/Bonnie “Prince” Billy: I wear my T-shirt all the time.

Heiken: The first couple of years, I benefited from lucky things like that. A lot of times people will come to me and be like, “I want to pick your ear about starting a thing.” It's like, I'm not good at this. I lucked out… It was just the perfect stuff happening at the perfect time. It's helped that we made something that lasted on its own. People don't really remember all that other stuff anymore.

Bissen: The other soft rule is: Know when you're playing and play to that time. A 3 p.m. set isn't going to be the same as a 3 a.m. set. People are sleeping in the room. Respect that. Moreso, use that as an opportunity. Playing music to a room of people sleeping is a really cool and unique thing to do.

Metzger: That is a great time to play, while people are asleep or falling asleep.

Draper: I like knowing that there are people literally lying down or feeling like they can do whatever it is that's most comfortable for them. There aren’t a lot of situations that you play where there might be somebody napping. That actually feels really good.

Elaine Evans, founding member of International Novelty Gamelan/multi-instrumental performer: I tend to include parts that get kind of abrasive. I like to go through an arc of things. And I was like, "I can’t be waking people up." I have to kind of change.

Draper: There's a trust that's going on. People are there. Even if they are sleeping, they’re doing that not necessarily because they're bored, but they are feeling so comfortable and they're trusting you. I feel so comfortable in this space that I can let all of my guards down, and I'm just taking things in and not having to worry about whatever other millions of things you could worry about… It's one of the most ultimate honors.

Oldham: It's one of the most accepting and relaxed environments you could imagine to be performing in.

Heiken: The first year, there were so few people [who slept over] that when they woke up in the morning, The Cedar gave everyone who stayed the whole night a ticket to drink free for the rest of the concert.

Bissen: Me and a guy named Tom, I can't remember his last name. He's a taper. We were the only two people that spent the whole night and didn't bring sleeping bags or anything, just kind of powered it out on some chairs. The staff were, in the morning, they're like, “Fuck yeah, we're so glad you guys spent the night. Here's some passes so you can just drink.”

Heiken: People were like, “Oh, I don't know if I'm going to sleep in here.” And then they went and saw that other people did it. They're like, “Oh, next year, I'm going to do it.”

Bissen: I also performed the first one. That’s how I met Luke. I approached him at a Retribution Gospel Choir show, actually, and asked him to do the drone. He ended up giving me a slot and that was my first ever solo or synthesizer or drone set.

Heiken: Alex is busy the whole time. At this point, I don't know. I couldn't go back to doing it all myself, doing what Alex does on top of everything else. He understands the drone, and he’s been there from the beginning. Alex is great.

Bissen: The third or fourth year, Luke posted on Facebook looking for stage managers, wanted to get people doing it in shifts. I signed up and did a four-hour stage manager shift. Then over the years, I just started doing more of that and other people were taking less of it, until, it was maybe my fourth year, I was just doing the whole fucking thing.

Heiken: There's almost like a high school reunion every year, people that you haven't seen. It's like you're somewhere where it's all your people. Usually, we're all out in the world with a bunch of squares. It's like a sportsperson at a sports bar or whatever.

Evans: We're generally pretty picky about where we're going to play because we just don't want to deal with the work for any kind of situation. But we're always excited about coming and participating in this. It’s just a special thing.

Heiken: It's just a perfect combination of a perfect audience of people who want this kind of weird, unusual, thoughtful kind of music. It’s just by concentrating it where it’s able to flourish because there’s a guaranteed space for it and there’s a need for it.

Bissen: It's empowering and it brings people up into it and, again, they go out and carry it forth into other shit like a weird fucking church or something. I feel like that's what I'm describing.

Heiken: It was very intentional, trying to foster that community that was already here. Now, it's kind of fed into it, which has made Drone Not Drones better, which has made the community better, which has made Drone Not Drones…

Weird Music for Weird People

Luke Heiken, founder of Drone Not Drones: It was stuff I already liked about the weirdos in the Minneapolis music scene and wanting to provide space—holding space, as the kids say—for weird music for weird people.

Scott Brown, Noise Quean Ant: The idea that you would have a favorite year or something like that is very, very difficult to consider.

Alex Bissen, IOSIS/stage manager and creative partner for Drone Not Drones: I don't think anybody would have a favorite year. I definitely don't. It's for a lot of reasons. So many of the people that perform it are coming again and again. It gets kind of mushy from year to year. I guess most people probably aren't attending the whole thing, but it's 28 fucking hours, man. The corners start to get pretty round.

Xopher Besinger, STNNNG: Some of the best ones have been Noise Quean Ant in the middle of the night. Any of those little just churning, all of a sudden it's three o'clock in the morning and someone's playing whatever, death metal noise drone stuff.

Caleigh Souhan, senior events manager at The Cedar Cultural Center since 2021: I absolutely always love International Novelty Gamelan. That's always my favorite.

Liz Draper, bassist/portal iii/Chama Devora: Paul Creager from the Square Lake Festival, he had some visuals going on, I want to say it was prairie or something… Basically, they were taking “This Land Is Your Land,” but it was a really weird, different direction. You maybe wouldn't know that’s actually what they were hinting at in the sound. Then, at one point, there were two Indigenous jingle dancers who came from the back and their dancing created the percussion. It was just a really beautiful moment.

Heiken: Lee Ranaldo's stands out because he hung a guitar on a rope and was swinging it around the room.

Besinger: Lee Ranaldo with the guitar hanging from the ceiling was great because that was a little bit of, most of the acts, most of the artists playing are heads down onto a laptop, onto their instrument, onto a keyboard. And Lee Ranaldo, that was a little bit more theatrical.

Heiken: There was one where STNNNG played and Xopher Besinger read these poems.

Besinger: I wanted to find something that would add to the protest aspect of it, and also maybe amplify an idea or something that people don't normally think about. The people victimized and affected by drone strikes.

They’re Landays, an Afghan Pashto poetic form. It's a rhyming couplet. And they're mostly, and I think maybe exclusively, composed by women, and they tend to be poems of grief, but they're also very sarcastic and are full of incredibly bleak humor. There’s this book, “I Am the Beggar of the World,” a U.S. poet, Eliza Griswold, researched and translated these poems and then put this book out as a collection. And the book is fantastic.

Heiken: He read some poems from that. They were doing this music and it was really getting droney, and he started to read. That was very emotional because of the reason why we're there.

Souhan: I think it went Paul [Metzger] into Cole [Pulice] into Cole with two other musicians and then Florina was two after that. That flow of it all and the fact that it never stops and things can really build, that entire evening just felt like the momentum never really stopped. It was absolutely impeccable.

Dane Cree, illustrator: Gaelynn Lea playing with Alan [Sparhawk], that was another set that was, I don't know if anybody else was tearing up, but I felt like the room was.

Heiken: Jon Mueller. That was not droney at all, but that was, in a way, the most drony.

Bissen: I'll approach you and be like, okay, what's your instrumentation? What do you need? And Mueller’s like, “I have two small tom drums.”

Jon Mueller, percussionist: What I did was really just focused on the pure tone of the acoustic drums, because ideally what happens is people start to think there is other stuff going on, that there's maybe some backing track being played. That's sort of the wonder of it is that it's just acoustic sound. You're hearing all this stuff that you start to imagine is maybe other things happening. It's not. It's just the instrument, actually. It's really beyond the instrument. It's the room. It's all the frequencies and everything you're hearing bouncing around the room.

Brown: That one was super weird and absolutely kind of mesmerizing.

Paul Metzger, banjoist: That set was wicked to me. That set said everything that I have tried to say.

Heiken: I had someone, he was in the green room when it started, and he was like, "This is the worst thing in the drone. What is this?" And he goes out, and once he's out in the room where it's happening, he was like, “Wow, this is the best part of the drone. This is amazing.”

Will Oldham, musician/Bonnie “Prince” Billy: I created a little section of my living room that had a guitar, a melodica, a couple of microphones, two or three loop pedals, and maybe two amps. I had just started seeing a woman [Eliza Hansen] who, now, I've been married to for almost a decade. We would get up and take our turns going over to this morning music station and creating things so that the morning would be filled with basically drone music.

She's a visual artist, not a performing artist. I was like, "Would you want to go with me? Because that would make it interesting." I'd go up there and if she wanted to perform, do our morning music thing essentially.

Metzger: There are all kinds of motherfuckers that hit the drone stage, all kinds.

Oldham: Everything was great until we went on stage and my wife, at that moment, realized that she had crippling stage fright like I’ve never seen before in my life. She was petrified. It was like she was in an underground torture chamber or something. She was just beside herself and it was like, well, somehow we've got to get through this hour of just being so chill.

Brown: There was one year that Alan Sparhawk did something that was really just kind of bone-rattlingly loud and noisy. That one I remember just rattling my cage.

Alan Sparhawk, musician/Low: There've been some really cathartic times. I remember playing there pretty shortly after my father died and I played my dad's cymbal. He was a drummer. I played cymbal. It was one time I had broken five ribs and I performed. I just kind of sang and made vocal sounds and made loops and stuff. And it was really excruciating. It was really painful.

Bissen: He just fucking ripped the most incredible set you've ever heard.

Draper: The one last year with Alan Sparhawk really stuck out to me. I knew places he was going or things he was experimenting with or what was coming out of him post-Low and post-the time I got to play with them in Low. But I wasn’t exactly sure what to expect.

Sparhawk: The drone always comes up during a very pivotal time of my life and ends up being kind of this vehicle for really expressing what the dead of the winter is doing to me.

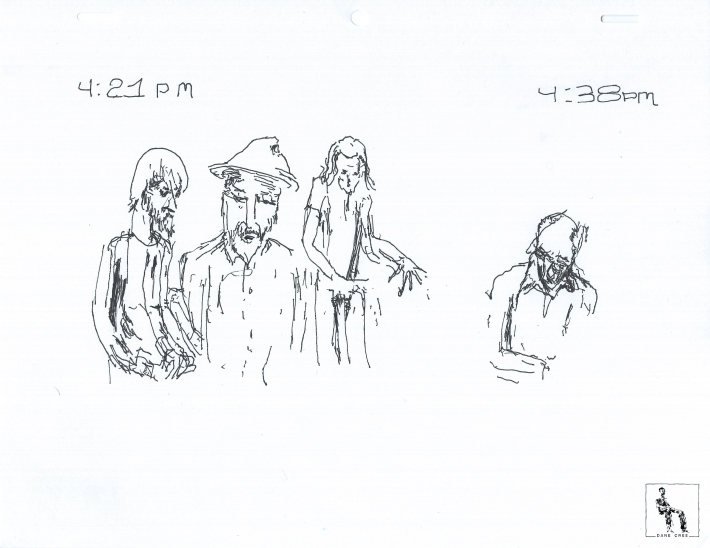

Bissen: Also, we have visual artists every year who are part of it. We got this guy, Dane Cree, he's an illustrator, visual artist. He showed up one year and just drew the whole thing. He drew every fucking performance of that drone, came back the next year, did it again.

Cree: I kind of like the endurance and performative nature of long stretches of drawing things in person versus taking photos and then going home and drawing those. Documenting: How does the music feel? What does the space feel like? What is it like to bump up against somebody while standing in a crowd?

Bissen: He donated his drawings to the drone last year. He gave one to me from the first year that he did it, and it's on my wall. It's one of my favorite things in the world, man.

Cree: The level of detail can depend on the amount of people. If there's one person, that person's going to get a lot of time from it. There's like seven or eight people up there, drawings get a little simpler. The images, the people are a little smaller as time wears on, the effort and the wear and tear on my eyes looking up and down, just my hand, and just being awake for that length of time also is impacting how I'm drawing and how I'm getting through it.

Nine Drones and 12 Years Later

Luke Heiken, founder of Drone Not Drones: We missed two years during Covid, and the second year I was considering doing it to an empty venue and streaming it. I don't know, maybe it wouldn't have been the same without the weirdness of the room. There's the power going on in the dark room. You go in and it's pitch dark and everyone's on the floor and there's music already happening.

Alex Bissen, IOSIS/stage manager and creative partner for Drone Not Drones: I don't remember why we started doing this mental exercise, but we were like, “What if we can't do it at the Cedar anymore?” Maybe we were worried that the Cedar was going to close. So, we're trying to figure out what that would look like and pretty quickly you realize there's nowhere else in this city where this would work.

Heiken: The first year after the pandemic, it started and it was like, we're back. People were ready for it.

Caleigh Souhan, senior events manager at The Cedar Cultural Center since 2021: People really missed it. Our numbers were definitely up.

Bissen: This would be entirely impossible if it weren't for the Cedar… You think back on that, you're like, “How the fuck did they agree to do this?”

Jon Mueller, percussionist: Seeing what Luke and everyone has built over the years with gathering this community of people… it’s really commendable because, for certain people who work in the realm of sound and music, that's what they want at every performance. They've figured out how to make that happen and continue to do it every year.

Will Oldham, musician/Bonnie “Prince” Billy: We see these festivals with 150 bands, but it's just 150 isolated incidents. It seems like such a wasted opportunity.

You're going to live and breathe and have 28 hours of your life potentially exposed to this musical cultural experience, which is going to give you ample opportunity for transformation and for reflection that maybe a two- or three-hour show isn't going to, or even a 10-hour festival experience, should you choose to subject yourself to such a thing.

Bissen: You're kind of grazing up against the other thing, which is the community. That's why people want to do it.

Joe Rainey, powwow singer/Bizhiki: Alex mentioned the drone and how cool it was and what it means, the cause that it's for. And that's one way that artists can be of help. I think that was the important thing, realizing the meaning of the night.

Liz Draper, bassist/portal iii/Chama Devora: We're all doing something very unique together. Everybody is like, I would say everybody, I shouldn’t speak for everybody, but it seems like everyone's welcome to share this experience which translates then into the larger community as a whole.

Paul Metzger, banjoist: It's not that common to come together and everybody just kind of brings themselves to receive the other person bringing themselves musically. It's special, and it's such a long period of time that it can have this mental effect on you if you're there for the whole thing.

Mueller: What is people's attention span today? What are they willing to commit to and what are they not? It was just very nice to see that in action and see the amount of people, the audience size, their willingness to give in to something.

Bissen: I've cried [when the final applause comes]. It's like, “We did it. It's over.” Celebrations. Sadness. The emotions from the music itself.

Alan Sparhawk, musician/Low: It's really unique, the collective feeling of it and sort of a humility to the bigger accomplishment is definitely pretty evident.

Bissen: This drone means so much to so many people.

Heiken: It was a perfect town to do something like this because we have all these people who are perfect for it. That's all tied into community. That's what makes it special. It's a community protest and a community collaborative art project. It's almost like the audience is part of it too. They contribute to the vibe or this symbiosis of providing space for musicians to do something special. Then the musicians deliver that. It's that self-feeding cycle where it's just, that's where the magic is, this magic that’s always there in the community.

These quotes have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Drone Not Drones 10th Anniversary

With: Earthen Sea, Spiral Joy Band, SWAM, Arrington de Dionyso, Amy Cimini, Matt Jencik, Chingiz Kam

When: 7 p.m. Fri. to 11 p.m. Sun.

Where: The Cedar Cultural Center, 416 Cedar Ave., Minneapolis

Tickets: $35-$40; find more info here.