David Byrne closed out a two-night stand at the Orpheum Theater in downtown Minneapolis Tuesday with a colorful multimedia humanist spectacle that dazzled all your friends with deep pockets and/or media connections and even tickled a jaded crank like me.

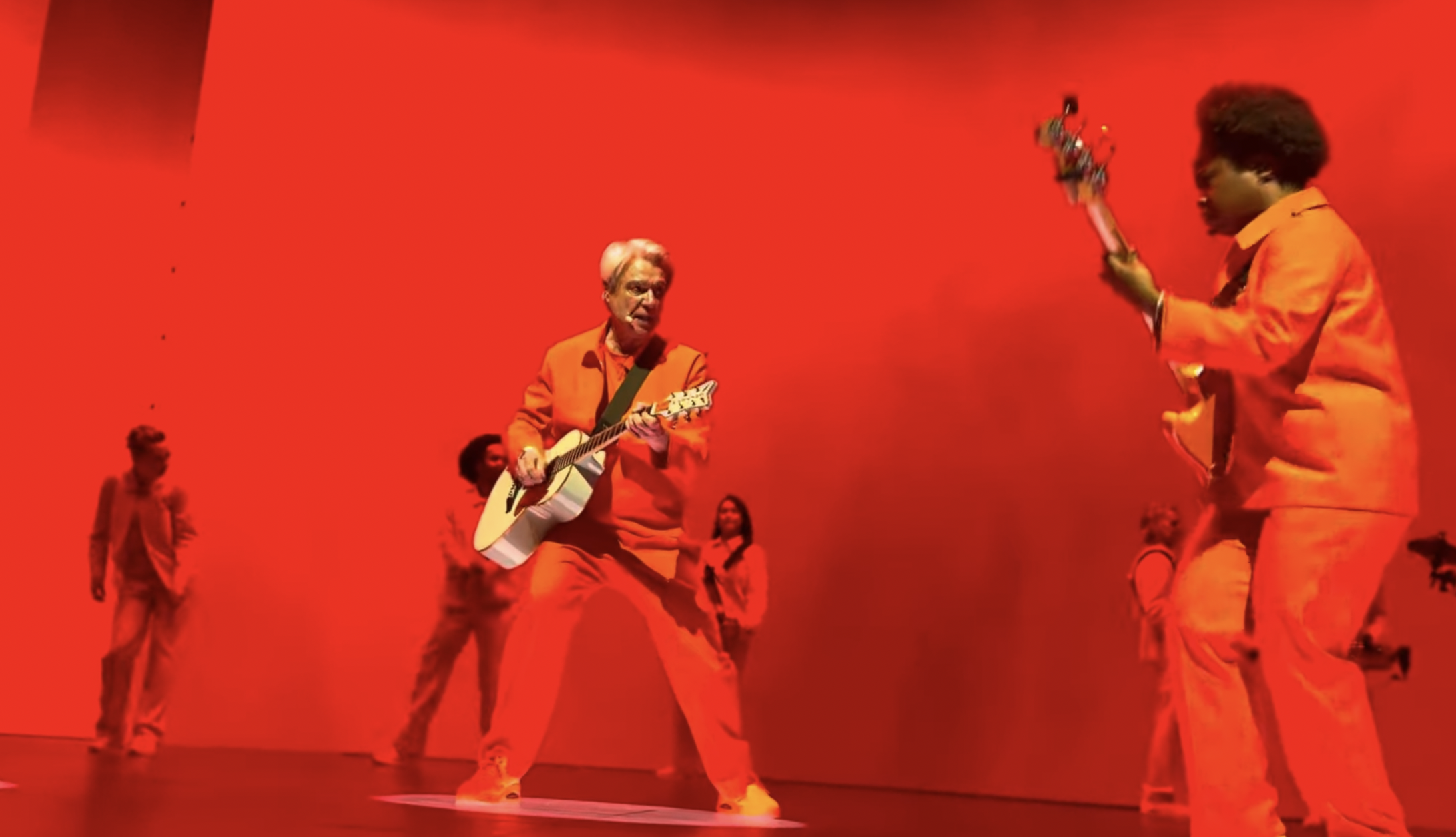

As on the celebrated “American Utopia” tour that passed through town in 2018 (which the less fortunate of us could witness in its beautiful filmed version), each member of Byrne’s 12-person backup crew is mobile and untethered by patch cords. The percussionists and the synth player had their instruments strapped around their necks. The stage was in constant motion.

All 13 performers wore loose orange pajama-like suits on Tuesday, like well-adjusted citizens of some playfully postmodern communal society. (At Monday’s show, the suits were blue.) These colors popped out against the huge panoramic digital screen around the stage, where images supplemented or commented on what was happening onstage.

This aesthetic, with its focus on rhythm and movement, matched Byrne’s aphoristically voiced philosophy, which struck a middle ground between childlike wonder and liberal truism. Even some of the weaker cuts from Byrne’s new album, Who Is The Sky? (why am I just now getting the title pun?), were recontextualized by the visuals and their proximity to Talking Heads faves.

I left the Orpheum elated. What was not to love? But as my serotonin inevitably dipped over the following few days, I asked myself instead, “What was so great about it?”

That’s what critics always ask, of course, and why we’re often dismissed as killjoys, insisting on a peek under the hood when most people just want to cruise down the highway.

Yet knowing how the magic happens doesn’t undercut the trick. And truly, there’s nothing more Byrnian than dissecting emotional responses to see how they’re generated. This is a guy who wrote a book called How Music Works, after all, and who has always approached human feeling as an outsider hoping to learn its ways.

To put the shows in Byrnian terms, we’d experienced a series of striking choices that, through some physicochemical process, brought us joy. So let’s examine those choices, that process, and yes, that joy.

Byrne opened his show in the afterlife. “Heaven is a place,” he sang to the accompaniment of violin, cello, and just a slight synth adornment, “where nothing ever happens.” A photo of the Earth as seen from space appeared behind him toward the end of the song, and afterwards, Byrne opined, “There it is, our only heaven.”

A turquoise guitar was then brought to him as the stage filled with his 12 accomplices: guitar, bass, synth, four percussionists, and five singer/dancers. Let me give a nod to Kely Cristina Pinheiro, the star of the night, whether slapping funky intros or interludes on her bass or bowing a portable electric cello.

Byrne moved on to “Everybody Laughs,” a straightforwardly universalist song from the new album that doesn’t get much deeper than its opening line (“Everybody laughs and everybody cries”). But it was enhanced if not upstaged by the series of images of colorful NYC oddballs that accompanied it.

Compared to the TED-Talky neurology lessons of his last tour, Byrne’s remarks seemed less structured. He showed us a slide of Minnehaha Falls, which he and his bandmates had visited that day. (He’d eaten at Diane’s Place the night before—he’s a very good tourist.)

Byrne introduced “And She Was” by telling a story about a girl he knew in high school who seemed happier than the other students. When he’d asked her what her secret was, she said she liked to lie in the fields out by the Yoo-hoo plant. Pause. “And I take LSD.” What could be more Byrnian than trying to imagine someone else’s acid trip?

During “T-Shirt,” an unrecorded song Byrne has premiered on this tour, the screen displayed (what else?) T-shirt slogans, some comic, some pandering to the sensibilities of the crowd, like “No Kings” or even “Minneapolis Kicks Ass.” From what I caught of the lyrics, I surmised that Byrne was having it both ways: Slogans are a simplistic and reductive way to communicate, he acknowledged, but that doesn’t mean they’re not effective or true.

On that point, Byrne recalled reading a quote from playwright etc. John Cameron Mitchell, which he paraphrased as “Love and kindness are two of the most punk things you can do right now.” From this, Byrne derived the true if limited sentiment “Love and kindness are a form of resistance.”

Byrne revisited oldies like the apocalyptically ecological “Nothing But Flowers” and “This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody),” which have surprisingly yet justly emerged as the best-loved Talking Heads songs. This segued nicely into “What Is the Reason For It?,” a distanced examination of affection that I think of as a warmer sequel to the Heads’ “I’m Not in Love,” followed by the similarly anthropological “Like Humans Do.”

Byrne cherry picked his solo work with curatorial finesse. He reached back to his first solo album, Rei Momo, for “Independence Day,” which had a nice accordion/saxophone Paris cafe feel; he preserved “Strange Overtones,” his Brian Eno collaboration.

Still, the stretches of solo material, especially the newer songs, did occasionally make it feel like we were earning the Talking Heads oldies. No offense but “Houses in Motion” and “Slippery People” just groove to a rhythmic synthesis that’s no longer in Byrne’s arsenal. Up against those songs, “I Met the Buddha at a Downtown Party,” where the old fella tells Dave he’s given up on enlightenment, felt like shtick. Was this Byrne’s way of telling us he is just a nor-mal guy?

When’s the last time you saw a rock performer give, well, a performance?

To state the obvious—which is always how to begin with this fellow—what’s special about a David Byrne show is that there’s dancing. Or maybe I should say “choreographed motion.”

What Byrne has learned from modern dance (he collaborated with Twyla Tharp while still in Talking Heads) is that the simplest movements, executed with deliberation, are inexplicably effective. As arranged by British choreographer Steven Hoggett, small unison hand gestures, or two groups of musicians marching in opposite directions—the sort of moves that even a 73-year-old can execute—had outsized effects.

Of course, if this had been a pop or R&B show in an arena or stadium, dancing would be assumed. No one would expect Taylor Swift or Beyoncé to stand behind a microphone and in front of a band for two hours and just sing.

But rock shows are expected to be spontaneous, or at least to simulate spontaneity. For nearly 50 years, David Byrne has been undermining the righteous fib that rock music can’t be premeditated and effective. With dancers, Byrne shifts the conventions from one genre to another with thrilling effect.

At times, Byrne’s Orpheum show flouted how planned it was. At one point, an onscreen video of the performers wearing animal heads moved in time with the real life humans onstage; at another, their names appeared onscreen, floating across a starry background to mirror their bodily movements.

As for the audience, It was up-and-down all night, never less than fully dialed in and appreciative, but on its feet for the more familiar oldies and sitting when the music got less familiar. “So fucking boring,” the woman next to me grumbled about her fellow showgoers when we all plopped back into our seats during a new track.

The critic Tom Carson once warily but not dismissively called Stop Making Sense “a control freak’s idea of paradise, less edgy theater-of-the-real than sublime avant-garde showbiz.” I thought of this when Byrne performed “My Apartment Is My Friend,” an ode to isolation from Who Is the Sky? We got a 360 view of Byrne’s home, including some bookshelves I quite greedily wanted to zoom in on, a place where he learned to cook in the early days of the pandemic. And thrived in isolation. As someone whose social anxieties were much eased by being trapped at home for months, I could relate.

Maybe Byrne’s apartment, like heaven, was a place where nothing ever happens.

That wasn’t the first time in the evening Byrne had mentioned the pandemic. “Sometimes we sing to strangers,” he’d stated earlier, as the screen shared clips of Italians in 2020 serenading each other from their balconies—a practice Byrne added, that stepped up considerably on Liberation Day, which commemorates the fall of Mussolini.

But only late in the show did I pick up on how much 2020 had shaped what seemed like a deliberately shapeless show, that Byrne was working through the pandemic still.

After an energetic reimagining of Paramore’s “Hard Times” that I only recognized when they reached the chorus, Byrne told us about a bike ride he took just as things were opening back up in late 2020. Hearing people chatter at outdoor restaurants, he’d had an epiphany: In spite of everything, “people really do want to be around each other.”

Typed out baldly here, that seems, like so many of Byrne’s observations, a bit of a duh. Yet there’s something moving about Byrne’s brain-first recognition of the need for community, especially viewed in light of his career arc.

“Irony” never seems like the correct word to use to describe Byrne’s art, because it suggests a self-imposed critical distance; Byrne instead works—at times, struggles—to bridge an already-existing distance, and to dramatize that process. And this was most apparent on Tuesday night in the three hits that closed his main set.

Byrne’s story as an artist, roughly, is about how he’s negotiated that gap between himself and humanity. He exaggerated his alienation in his earlier years, allowing us to recognize the disorientation that each of us share in some way. As James Wolcott memorably wrote at the time, Byrne had “a little-boy-lost-at-the-zoo voice and the demeanor of someone who’s spent the last half hour whirling around in a spin dryer.”

We revisited that isolated young Byrne when, over an insistent snare beat, he strolled across a spotlight. Then his shadow began moving on its own, striding forward until the circle of light was blotted out. The snare revealed itself as the start of “Psycho Killer,” a song absent from Byrne’s set for 19 years until this tour, and he credited the late downtown musician Arthur Russell with the arrangement.

Beginning with Remain in Light in 1980, Byrne was liberated by funk and polyrhythms from around the world. On songs like the inevitable “Once in a Lifetime,” which closed his set, he attempted to balance his alienation against the flow of the cosmos, to escape the solipsistic perspective of urban paranoia.

Between those two oldies came “Life During Wartime,” and if you were thinking it felt more applicable these days, Byrne was right there with you. Toward the close of the song, the screen showed clips of Homeland Security assaults on U.S. cities and their residents. What had once been a younger man’s projection of his unsettled mind was now something like a shared protest song. Byrne was one of us after all.

But that wasn’t quite the end. For an encore, all 13 performers gathered in a circle around a bare lightbulb for the gospel-inflected “Everyone’s Coming to My House”—the house he’d inhabited alone in 2020. And then, having invited us to his house, he burned it down with one more Talking Heads song to end the night. What did it all mean? I can’t exactly say. But the better question is, what was not to love?

Setlist

Heaven

Everybody Laughs

And She Was

Strange Overtones

Houses in Motion

T-Shirt

(Nothing but) Flowers

This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody)

What Is the Reason for It?

Like Humans Do

Don't Be Like That

Independence Day

Slippery People

I Met the Buddha at a Downtown Party

My Apartment Is My Friend

Hard Times (Paramore cover)

Psycho Killer

Life During Wartime

Once in a Lifetime

Encore

Everybody's Coming to My House

Burning Down the House