This July 26 marked the 250th anniversary of the United States Postal Service, and if I were president, we would have had a national holiday, parade, and gigantic party to mark the occasion.

Nothing gets my red-blooded American heart soaring with patriotism quite like the USPS, a marvel of public service that enables you to send a postcard across the Pacific for 61 cents. Like an angler with his quarry on the line, I get the shakes when I'm putting a stamp on a letter.

Last year, I started my own humble mail operation, a monthly handwritten newsletter detailing some notable lunches I had the past couple of weeks plus a bit of nonpolitical, non-topical writing. The project, Nick's Lunch Newsletter, has blown up beyond my initial expectations, with friends and strangers alike saying they loved what they were getting.

Perhaps as a result of launching my own USPS-based newsletter, I started noticing more and more of these mail people in the world. A guy who paid for an ad in Harper's just asking people to send him a postcard. A classified in County Highway on behalf of a married Milwaukeean seeing platonic male pen pals. (He's cool, I swear.) A friend told me about a high school buddy whose response to fatherhood was buying a typewriter and sending greetings to his old chums. It confirmed my burgeoning theory that people are generally quite sick of the internet, and are ready to get a letter.

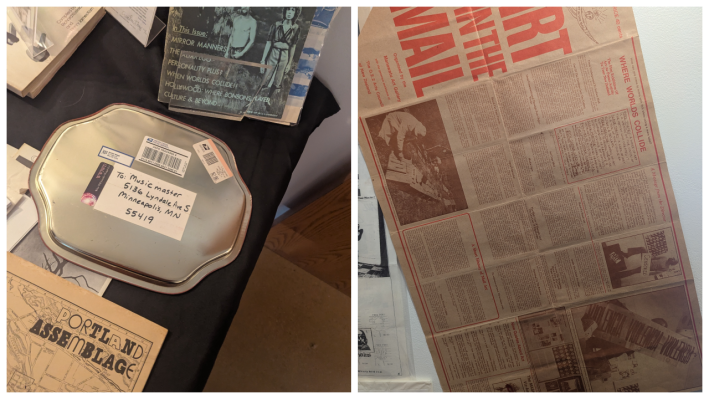

On the tip of another friend, I mailed a copy of Nick's Lunch Newsletter to the famed Musicmaster, a Richfield resident who describes himself a "mail artist." In return, I received a gigantic envelope covered in bespoke stickers: a skeleton family buying candy, a rat, the Grateful Dead's "Bertha." Inside was an assortment of paper ephemera that seemed to come from all over the world, from all different eras. There was a lithograph of someone's house cat, a receipt from a Parisian mini golf course dated 30 July 1995, a 1978 piece on blue printer paper called “Untitled (2 women with globe).”

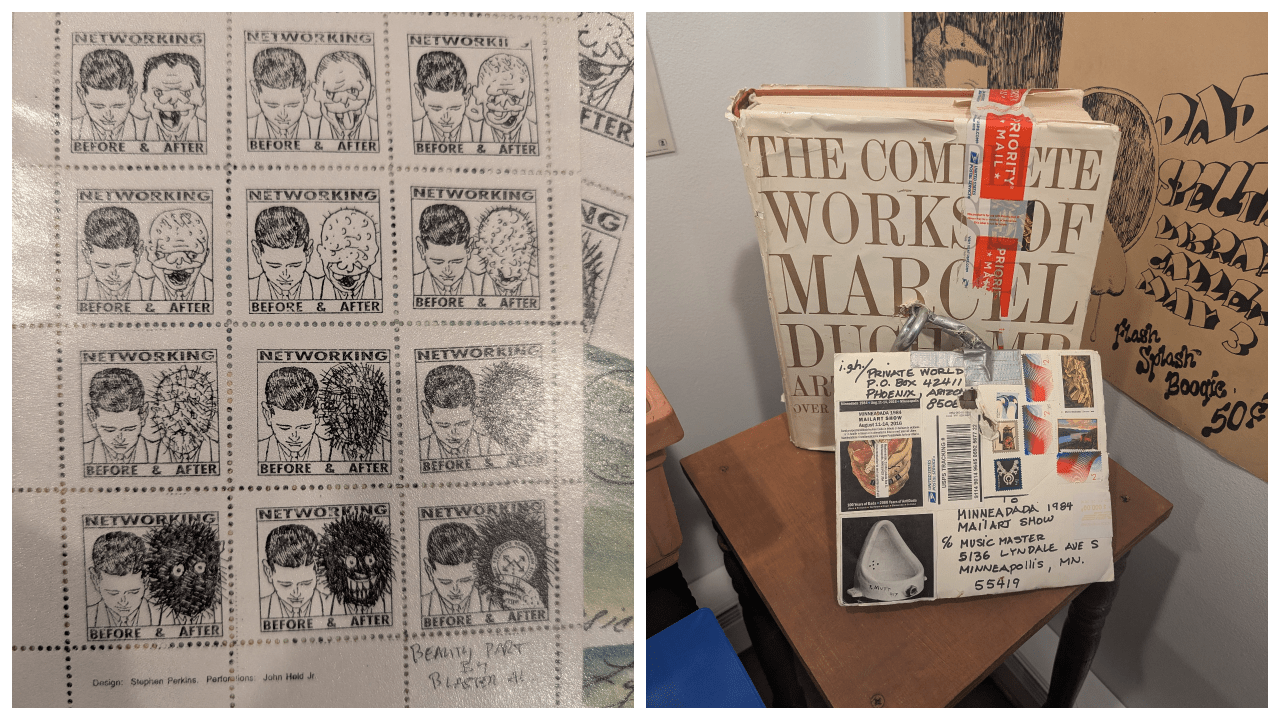

And there was an invitation to an exhibition, "Decades of Mailing It In," advertising "1,000 pieces of correspondence art and 40,000 pieces of mail yakked up by Musicmaster's mailbox since 1972." On the back, Musicmaster had drawn me a space alien and circled the "Hey Mail Artists" greeting. I felt as though I was being inducted into a secret society.

Entering the exhibition, which took place October 10-12 at Squirrel Haus Arts, I was surprised to see that the numbers listed by Musicmaster on the flyer were only a slight exaggeration. The walls were covered in 8.5"-by-11"-sized samples of significant subterranean movements, everything from punk zines to Tijuana Bibles to Dadaist visual poetry to collage to the Church of the SubGenius.

"Mail art was part of the nascent boom in zine culture," Musicmaster told me. "It predates punk."

For Greet-O-Matic, a collage correspondence artist, the process of his art was far more significant to him than the product itself. "It all goes back to my love of getting things in the mail as a kid—collecting cereal box tops, sending them off, and getting a prize. The process is very much one of clearing my head," he said. Greet-O-Matic told me that in the flow state of creating his pieces and mailing them, he often doesn't even recall what exactly he is sending to other people's mailboxes.

"I get kind of culty when I talk about mail art," admitted correspondence artist allison anne (who stylizes their name in lowercase letters). "It really changed my life." Anne is a correspondence artist who discovered old letters as family heirlooms, and didn’t learn about the mail art tradition until later, as an unwitting member of the scene. “Everyone thinks they invented it,” Anne said, describing the excitement of finding other people who love mailing odd things to each other.

“You apply by joining and join by applying,” The Sticker Dude, a New York-based mail artist, remarked in a panel. “Mail art is a utopian practice—it’s people participating, cooperating, and exchanging without worrying about money.”

Near the center of the back room of Squirrel Haus was an antique perforator where the mail artists were pressing their "aristamps," a mail art version of personal postage that acts as a kind of signature. A gigantic table in the middle invited patrons to make their own collages. As I sat down, The Sticker Dude slapped something on my chest—a sticker saying “Black Tie.” “Now you’re dressed for the occasion, ha ha,” he said. A woman in a postal service uniform handed me a slip and I was asked to record my recurring dreams on a slip for live interpretation the next day. I asked her if she was a letter carrier; she responded, “Do you mean in here, or in real life?”

The pseudonyms, the secret networks, and the Dadaist codes on the wall gave me a sense of being in the room with secret agents. “[My legal name] is just some guy, but Musicmaster is the person you see in your mailbox,” Musicmaster said. Greet-O-Matic told me of international correspondence beyond the Iron Curtain, where artists would mark envelopes to see whether state censors had steamped open the envelopes.

I finished my own piece of a collage art postcard, wanting to take it home and show it to my wife. After returning from the bathroom, I noticed it had been whisked off somewhere. I imagine it will soon be traveling via post to somebody, somewhere.

Correction: A previous version of this story identified allison anne as a second-generation correspondence artist, which they are not.