In April 2022, my wife and I attended our first concert since before the pandemic: Bob Dylan at the Tulsa Theater. As we approached the venue I suddenly realized how nervous I was about being in a room full of people. But when a woman with pink hair popped her head out of the car she and a friend had been hotboxing to loudly compliment my wife on her quilted jacket, that seemed like a good omen.

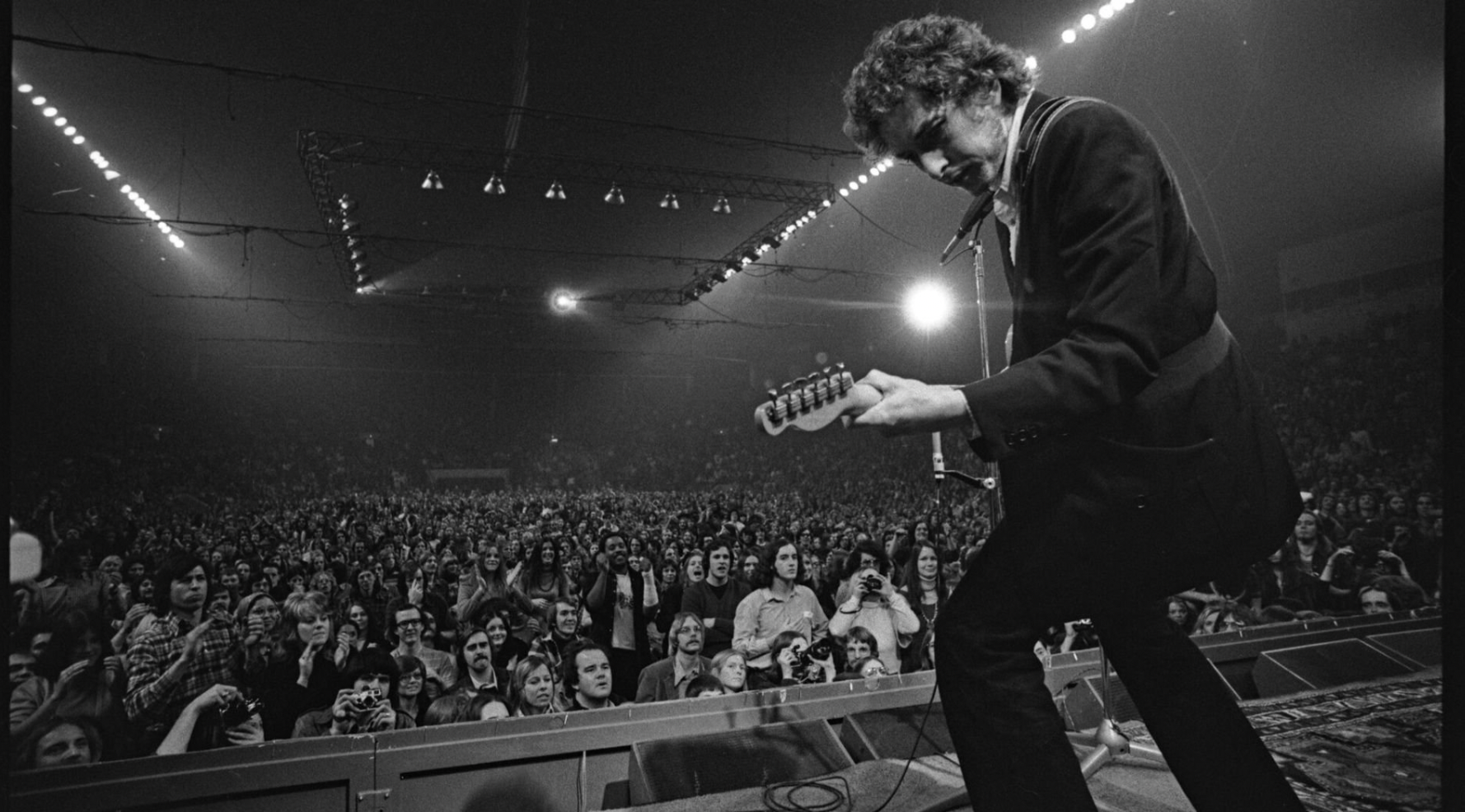

Bob and his band materialized to play most of Rough And Rowdy Ways, with a few classics sprinkled into the set. They opened with these fun, scratchy and incoherent versions of “Watching The River Flow” and “Most Likely You Go Your Way And I Go Mine” and then slowed down to savor the new material, especially “I Contain Multitudes” and the weary, romantic “I’ve Made Up My Mind To Give Myself To You,” which Bob sang with full commitment. I felt like I was floating.

But while I was curious about the song selection, I also wondered whether the little fella would say anything on stage about the Bob Dylan Center, the museum housing tens of millions of dollars’ worth of his personal effects that was soon to open three blocks away from the stage. He did not. But he did display a small hand towel on his piano that night. I heard from other concertgoers that it came from a Tulsa Drillers baseball game, held in the stadium a little further down the same street as the Bob Dylan Center.

Rather than tour the museum, where thousands of artifacts—mysterious lyric notebooks, unheard studio outtakes, handwritten letters to celebrity confidantes—will remain on display well after his death, Bob Dylan had decided to take in a minor league baseball game while he was in town. Perhaps it was another act of feigned indifference, or maybe he just really wanted to enjoy some sunshine and popcorn. Bob moves in mysterious ways.

This weekend, Steven Jenkins, the director of the Bob Dylan Center, will arrive in Minneapolis for the Sound Unseen festival, where he’ll screen an hour-long concert documentary edited together from footage in the Bob Dylan Archives.

“I've been referring to these as ‘50 Years in 60 Minutes’ because you have this wide sweep through Dylan's ever-changing career,” Jenkins says. “This by no means is meant to be a definitive look at Dylan, as if there could be such a thing. And this isn't a Scorsese-scoped documentary.”

The film runs chronologically, as Dylan performs some of his best known and most obscure songs in various settings.

“They all reveal different facets of Dylan, as a songwriter, as a performer, as someone who's very aware of the camera and how compelling a figure he is on screen,” Jenkins says. “Even when he's feigning nonchalance I think he's quite aware of the camera lens and what he's doing—in collaboration with it.”

The film has only been screened publicly a handful of times, and its northward expedition to Minneapolis presents a unique angle into the life and career of the 83-year-old Dylan.

You may now wonder why Dylan decided to set up his museum in Tulsa of all places. Why not Minnesota, where he was born? Or New York City, where his career first took off? Or even Malibu, where he has a home?

The decision may stem from the fact that Dylan still reveres Woody Guthrie as much as he did when he visited the ailing Oklahoma folk legend at Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital in 1961. According to Jenkins, Dylan and his manager Jeff Rosen came to Tulsa in 2016 to see the Woody Guthrie Center, which had opened three years earlier.

“Dylan was genuinely impressed with the Woody Guthrie Center and the way that the collection was being stewarded, the way that materials were being exhibited, the context around the materials,” Jenkins says.

Now the Dylan and Guthrie Centers stand together in the same rehabilitated brick building in the Tulsa Arts District, twin monuments to wandering songwriters.

I should stress that the center itself is extremely cool, and, like a great record, rewards return visits. An interactive exhibit shows the countless revisions that “Jokerman” went through. An entire bag of mail reveals the fan mania for Dylan in the '60s, including a particularly affecting letter from a machine gunner in a U.S. infantry unit serving in Vietnam. Memorabilia abounds, from correspondence with Johnny Cash to an insanely sick custom-stitched 1978 U.S. tour jacket. The staff are a friendly bunch who work hard to bring in new exhibits regularly.

The Archives at the Center are also growing. There are now three quarters of a million individualized audio files in its digital system. And as notable musicians pass through, the BDC often adds to its stash by interviewing them about how Dylan’s work and creative processes have informed their own.

Every time I leave the Bob Dylan Center I feel recharged, much the way I felt walking out of the show in 2022. There is something inspiring about a man bringing new songs into the world at an age when his contemporaries (those few who are still alive) have become tribute acts. And therein lies a unique tension that haunts the center: How do you educate the public on the life and catalog of an artist whose body of work remains incomplete?

“Part of the thrill of being a fan is, you know, the ineffable. As much as you listen and as much as you study and pour through the lyrics. And there's a mystique there at the core that is wonderfully unsolved,” Jenkins says. “We want to ask more questions than we want to provide answers.”

For what it’s worth, Dylan still hasn’t visited his own museum. Perhaps this is more feigned indifference? If you keep your past at arm’s length, I suppose, you can stay uninterrupted in the present.

Fifty Years in Sixty Minutes: Films From the Bob Dylan Archive

With: With pre-movie performance by Courtney Yasmineh and post-movie Q&A with curator Steven Jenkins

Where: Parkway Theater, 4814 Chicago Ave.

When: Sunday, Nov. 17, 11:30 a.m.

Tickets: $20 advance/$25 door; more info here