The day after Bill Underhill vanished, the headlines were inextricably reflective of the era.

Mickey Mantle, following much speculation, had stepped away from baseball. Almost 20,000 POWs huddled in Saigon. East and West Germany were locked in "a war of nerves" over Berlin roadways. And yet other stories from the March 2, 1969, Minneapolis Tribune could convincingly run at any point during the next 60+ years: abortion reform, gun control, and a culture-war proxy battle surrounding the morality of Christian Marquand's sex farce Candy all graced the frontpage.

Closer to home, residents squabbled over the need for skyways along Nicollet Mall, with one letter to the editor decrying the potential loss of "esthetic value”; others felt compelled to protect shoppers from the weather. It was cold the previous Saturday night, with a reported low of 15 degrees and light snow. That’s the winter scene a jacketless Underhill walked into as he left a Dinkytown party, never to be seen or heard from again.

Bill’s disappearance wouldn’t ever appear in any newspaper, and it would be mostly forgotten for decades. Until, just recently, two teams of sisters joined forces to discover what happened to the University of Minnesota student after he stepped out that door.

Who Was Bill Underhill?

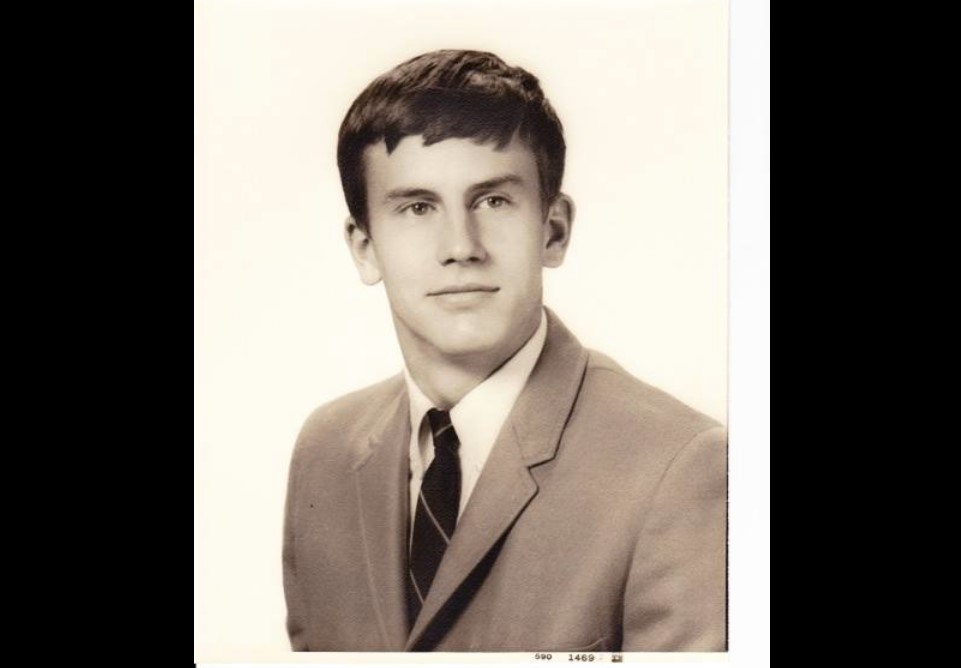

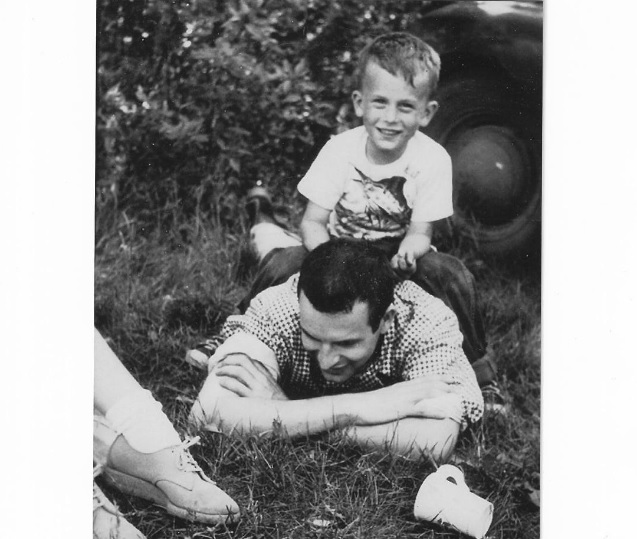

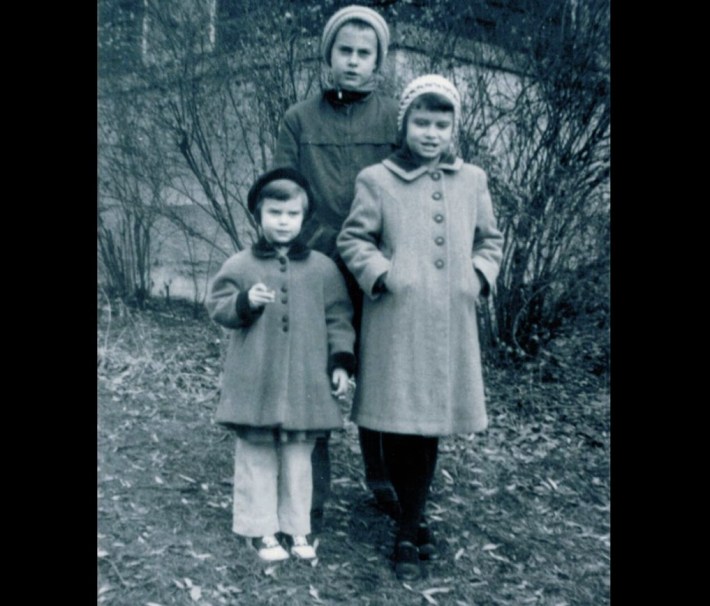

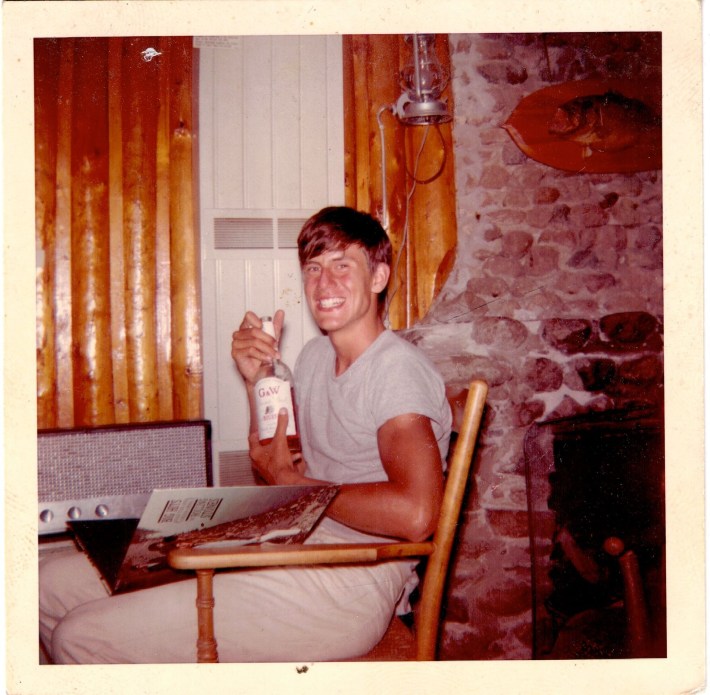

“I thought he was pretty cool when I was growing up,” Mary Underhill, now 67, says of her older brother. Parents James and Anne Underhill had moved from Duluth and made a home in St. Paul’s St. Anthony Park neighborhood, where they’d raise Bill, Sarah, and Mary. Dad was an ichthyologist at the U of M, and his freshwater fish studies would take the family north to Itasca State Park every summer.

Bill, who survived a childhood bout with polio unscathed, explored his passion for fishing during those mornings on the Mississippi River headwaters. The young angler had “a tough relationship” with his father, Mary says, one that could descend into “frightening” arguments as Bill grew older. But they’d bond over fishing walleye on Lake Itasca and, just months before Bill disappeared, smelt along North Shore streams. Bill kept detailed journals to catalog his two favorite hobbies—one for fishing, which he’d update up to four times per week, and another for weightlifting.

At Murray High School, Bill joined the wrestling and football teams. "House of the Rising Sun" was on steady rotation, as were the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan. Beer, pot, and sometimes speed entered in the mix, Mary reports, though nothing out of the ordinary for a teen in the late ’60s. Darker episodes would emerge, like the time he spent days hospitalized after swallowing a bottle of aspirin around Christmas 1965. Bill, who dabbled in street fighting, was nabbed by St. Paul cops under suspicion of burglary in ’68, an arrest the family wouldn’t learn about for almost 50 years; a childhood friend said it was likely related to snooping inside cars in pursuit of booze. (Local agencies were unable to locate any arrest record.)

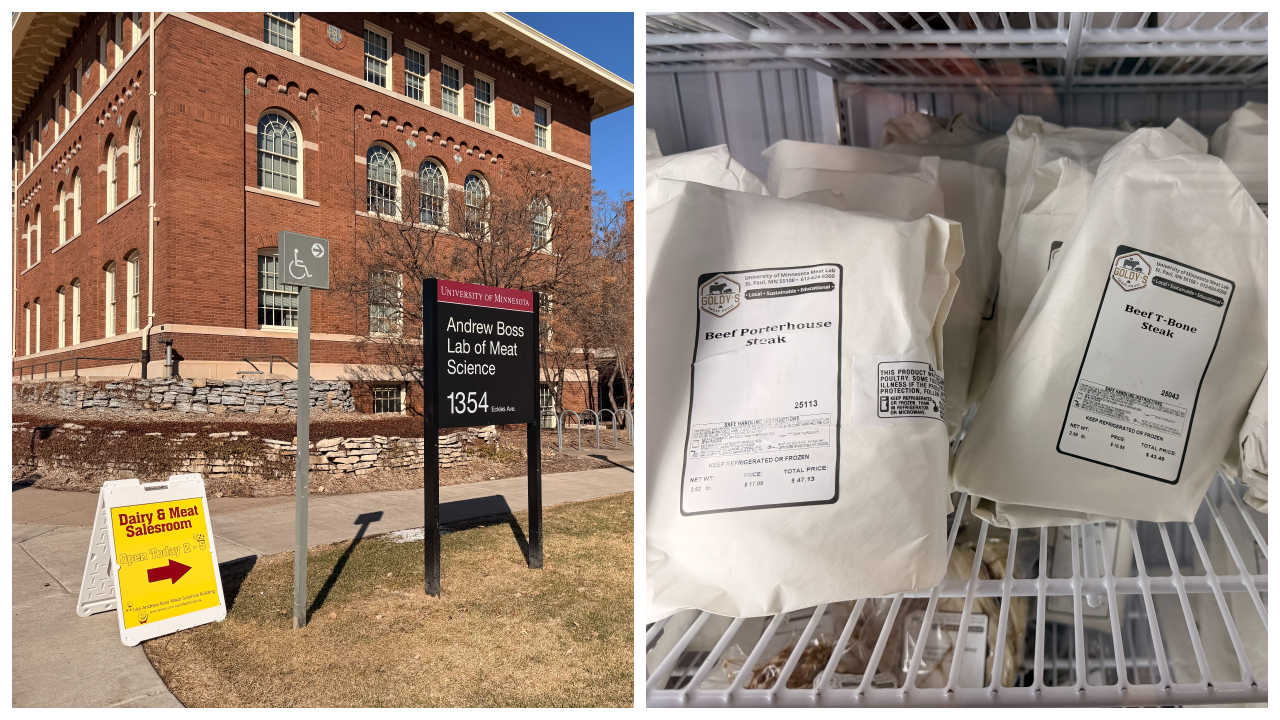

In 1966, Bill enrolled at the University of Minnesota shortly before his sister Sarah, who’s one year his junior. He’d study liberal arts, though Mary suspected he’d eventually follow in his father’s footsteps and enter the world of biology.

“He was shy in some ways, but other than that, fun,” Mary remembers. “Growing up he was a really avid skateboarder. He had very different groups of friends, it sounds like he connected to a lot of people. It’s been like putting a puzzle together about who he was. To me… he was just, very tall, very handsome, always kind to me, gentle… ya know, my older brother.”

The Dinkytown Party

It’s not even certain when Bill went missing, let alone what happened to him once he did. March 1 seems to be the most likely date, according to the family.

“This is the hardest of the cases to solve, because we don’t have a body. We don’t have a starting point,” Joe Kennedy, a top international cold case expert, says with a friendly North Carolina drawl. “If I had this case, man, it’s all about that party in Dinkytown. Who’s at that party, who was with him last, the last person who saw him alive was critical. One-hundred percent the focus has to be on Dinkytown.”

Bill’s evening began studying alongside Sarah at their childhood home on 1200 block of Raymond Avenue. (Both siblings commuted about two miles from St. Paul to the East Bank for classes.) Eventually, Bill ended up at an apartment party near 14th Avenue and 5th Street. Mary would later hear that the guests, mostly friends from high school, talked at great length about heavy topics such as the Vietnam War and, at some point, suicide. Bill wasn’t a vocal anti-war activist, and his draft physical was scheduled for sometime in early March. (The family would later learn Bill’s draft number was quite high, meaning he probably wouldn’t have been shipped off to fight in Southeast Asia.)

Nobody knows what happened in the moments before Bill went for the door. At some point, either just as he left or shortly thereafter, a partygoer ventured outside in search of him. Nothing.

Sometime that night, between 9 and 11 p.m., Bill had placed an ominous phone call.

“He called his girlfriend, Terri… and she took it that he was breaking up with her,” says Mary, who learned of the girlfriend’s existence in just the past few years. “He said, ‘I’m going away, I gotta go, and I hope that you’ll always be the good person you are.’ She wanted to know where he was, and he wouldn’t tell her. He sounded very sad.”

Days later, a friend returned Bill’s leather jacket to his parents. His wallet was inside. Bill would be reported missing that week as friends started calling the Underhill home looking for him.

“I always thought he’d come back by my birthday, which he’d circled in his calendar. But he didn’t,” Mary says. “It was kind of different back then. Nothing was ever really done to find him.”

Days would pass, then weeks, months, years, and decades. The use of Bill’s social security number never triggered an alert. His final paycheck remains uncashed, his dormant bank account deactivated long ago.

“There was really this sense of shame that this happened, like, ‘How can you not know where your family is?’” Mary says, noting that she’s visited with several psychics over the years. “I think we were all sort of lost about it.”

Mary believes her parents carried a heavy burden through the end of their lives. The family didn’t talk about Bill. At one point, however, their dad tried connecting with someone in Canada familiar with draft runaways who fled to that country. Their mom would often dream of Bill returning to the dinner table, and she’d place calls to radio stations whenever a body was pulled from the river. They’d die, in 2000 and 2013 respectively, without any resolution over the whereabouts of their son.

“It was always on mom's mind,” Mary says.

At Last, a True Push to Find Bill

Bill’s memory never strayed far from the minds of his sisters, either.

In 2003, the skeleton of a man missing since the ’70s was unearthed in Cambridge, Minnesota.

“The BCA had done a composite sketch, a model of the skull, and someone who knew Bill called our mother and said it looked like Bill,” Mary remembers. It wasn’t Bill, though the event inspired all the Underhill women to submit their DNA to a national database that can match human remains to surviving family members.

Just this past January, the family of Donald Rindhal received remarkable news: The bones excavated in ’03 belonged to Rindhal, bringing closure after decades of painful uncertainty. “If Bill’s bones were ever found, they could be matched to us,” Mary says, citing the Isanti County saga as an immense source of hope. Improved DNA forensics technology has revolutionized the way cold cases are investigated in recent decades, leading to breakthrough cases like a double Montana homicide from 1956.

Kennedy, the veteran cold case investigator, says an explosion of true-crime podcasts and books have enlivened interest in the field. (His book, Solving Cold Cases, comes out this fall.) And it’s a vast field. There are currently 21,789 open missing person cases in the U.S., according to the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs), including 191 in Minnesota. Each year 600,000 people go missing, per NamUs, and 4,400 unidentified bodies are recovered.

The search for Bill ramped up in 2015, when Mary and Sarah launched the Facebook page “William Campbell Underhill-Missing Person.” That’s how they connected with Terri, Bill’s girlfriend who’d never met the family. “She said that she found out Bill was missing because our mother had called her… somehow my mom found her,” Mary says.

The Underhill sisters would attend Bill’s 50th high school reunion as a means to acquire more intel on his disappearance. Mary made a guest appearance on the popular Unfound podcast the following year. She’s beginning to feel a real sense of momentum, even urgency.

“It was just amazing how it really took off,” Mary says. “I can almost not talk about it without crying. It really feels like this discovery of who he was.”

That discovery process attracted some professionally trained muscle this past April. (It also attracted a random Qanon nut; the sisters politely declined his help.) But they gladly welcomed Holly Keegel, a retired Minneapolis cop with 30+ years experience, and her dedicated sister Heidi to the search party.

“Ever since I was growing up, it always bothered me,” Holly says of missing person cases. “You’d see the kids on the milk cartons, then Jacob Wetterling. Really, with that case, it made me more diligent going on calls for missing persons. It became my passion after I retired.”

The Underhill-Keegel partnership began with extensive phone conversations between the pairs of sisters. The Keegels know most minds jump to three possible conclusions: Bill took his own life, Bill’s life was taken by someone else, or Bill relocated his life to avoid the Vietnam War.

“If they solve this case, man, they’ve done something,” says Kennedy, who happens to be working on two unrelated cold cases from 1969. “That’s a Herculean effort.”

Holly is approaching the case as if they received a phone call the morning of March 2, 1969. That means interviewing original sources, mapping the area of the disappearance, and searching citizenship, military, school, and police records.

New leads keep bubbling to the surface, including a renewed look at the street-fighting scene of the late ’60s, which included brawling gangs with names like the Baldies, the Greasers, and the Animals. Holly has even contacted the Hennepin County Water Patrol to get a sense of what historic Mississippi River freeze levels were like that winter.

“The more you hear about Bill, you get attached,” Heidi says. “You just want to keep working the case. It’s been pretty much every day. Especially working as sisters, together, it’s just so heartbreaking.”

Adds Holly: “You’re constantly thinking about it. It’s been so rewarding to take the pressure off Mary and Sarah. To go on this journey with them, so they don’t feel so alone. Our goal is to give them information, and maybe fit these puzzle pieces together.”

For the Underhill sisters, that effort could bring a long overdue sense of closure for the lost brother who remains a huge presence in their lives.

“It feels like there’s a lot of momentum,” Mary says, voice audibly lifted. “Sarah and I talked with Holly and Heidi on the phone for a couple hours, and I think it was the first time that she and I had cried together about this. I might die and we’re not gonna know. Neither my sister nor I have children, so we’re the last of our family.”

Anyone with information about what happened to Bill Underhill is encouraged to reach out via Facebook.