It’s a familiar dive-bar tableau. AC/DC playing over background chatter. The smell of stale beer mixing with greasy bites and intermittent wafts of smoke from the patio.

The ’70s rockstar outfits, mullet wigs, and cow costumes feel less familiar. As does the Joe Dirt impersonator sweeping underwear off the stage.

This is air guitar.

That’s the kind of declarative, no-frills statement a regional air guitar championship might make, tongue firmly in cheek, in a Spinal Tap-like declaration of rock ‘n’ roll reverence.

But this is air guitar. Goofy and nostalgic, an instrument-free embrace of unfettered joy.

A couple of hours before the May 17 U.S. Air Guitar Regional—dubbed the Minneapolis Regional and held at Route 47 Pub in Fridley—I didn’t know that. At least, not entirely.

While air guitar competitions have existed for decades (the World Guitar Championships' inaugural competition was held in 1996), I wondered how air guitar endured beyond its spotlight moments like the 2006 documentary Air Guitar Nation or brief appearances on ESPN’s The Ocho. Had it succumbed to the seemingly omnipresent desire for virality, to helicopter into something seen as kitschy for a photo before fading away like third-wave ska?

Or maybe it had evolved into a rebuke of technocapitalism’s demands on our attention, a way to do something in the tactile world, even if the guitars are ethereal.

The Lost Heartbreaker—I’m sticking with stage names because, in this space, Rob Nechanicky is The Lost Heartbreaker—thinks maybe it’s all those things and more.

As techs prepare the stage behind the Air Guitar Hall of Famer from Minnesota, he recalls his first competition. “That was the first and only time I was really disappointed,” he says of his second-place finish.

The next year, in 2007, he practiced hard leading into the regional held at the Varsity Theater. “There’s probably about 700, 800 people there. I went out, I did my performance, and the whole place erupted,” he says with a smile, tucking long brown hair behind his ears. “To this day, it was one of the most memorable things ever. Like, ‘Oh my god, I just made this whole place freaking go nuts.’”

He pauses to wave at two men entering the bar, unmistakably here for air guitar and not the loaded nachos.

“I actually felt like I won at that point in time. I was like, ‘Oh, it doesn’t matter what happens anymore. What I just received from the crowd is totally amazing.’”

He didn’t win. In fact, despite being a Hall of Famer and the emcee for the Minneapolis Regional, he hasn’t won on the national stage. And he seems genuinely unbothered by that.

Air guitarists filter in, hug one another, pop into our conversation to say hi to The Lost Heartbreaker. “You never have to win. It’s just the best fucking time ever,” Rockstache interjects.

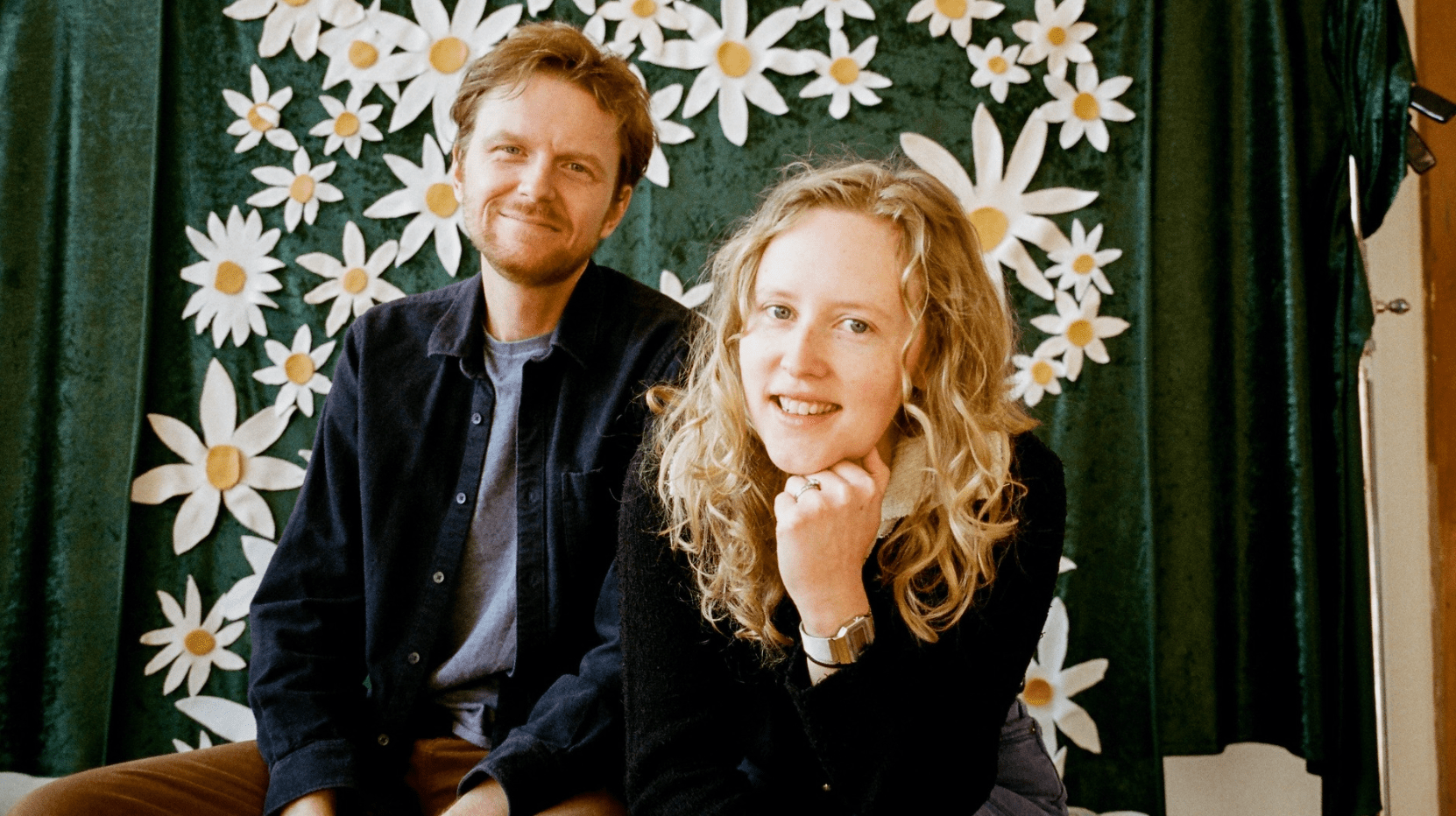

The air guitarists greet one another with the familiarity of neighbors, but many have traveled hundreds of miles to compete. Eric “Iron Dragon” Fox arrives from Kansas City. His wife, Beth Melin, whom he met at an air guitar event, is “air traffic control,” aka the person in charge of music.

The current national champion, Cole “Slappy Nuts” Lindhbergh, has flown in from Atlanta to perform during halftime. AirMazon Prime, aka Hennessy Williams, hosts a regional in Cape Canaveral, Florida, but has come to Minnesota to compete for a place in the National Finals.

This space, unserious as it may be in some ways, is also sacred for those who practice all year in anticipation of making a run at the national stage.

“Air guitar saved my life,” Lightning Mike tells me as his wife of more than two decades, Cathy "The NorthAIRn Lights" Myer, nods. She’s recovering from a major hip surgery, but plans to perform for the first time in the Minneapolis Regional.

When she walks away, Lightning Mike says he’s dedicating his song, a metal rendition of “You Are My Sunshine,” to his wife. He’d already qualified for the National Finals, but still wanted to be here. So he planned to intentionally disqualify himself by using an inflatable guitar, later affecting a heel-turn outrage with the bluster of a professional wrestler when the judges announced his disqualification.

The faux guitarists file off to prepare for the opening ceremony, an unrehearsed group medley that instantly reveals just how goofy the competitors are and how seriously they take supporting one another.

When individual performances begin, they holler for each other, throw panties on stage (those can be procured for $2 at a table by the stage, with proceeds, like all the event’s proceeds, going to the SACA Food Shelf), and generally applaud their “airness.”

(We probably need a short primer on the rules at this point: Three judges score acts in three categories, one of which is the “you know it when you see it” catch-all of “airness.” In the first round, everyone selects their own song. Five semifinalists move to the second round, where everyone performs the same song, selected by the crowd.)

This support is as present for veterans like Rockstache and Airgasmic as it is for rookies like Udderly WandAirful, who went all-in on a Will Ferrell interpretation of “(Don't Fear) The Reaper” with a cow costume adorned with a cowbell.

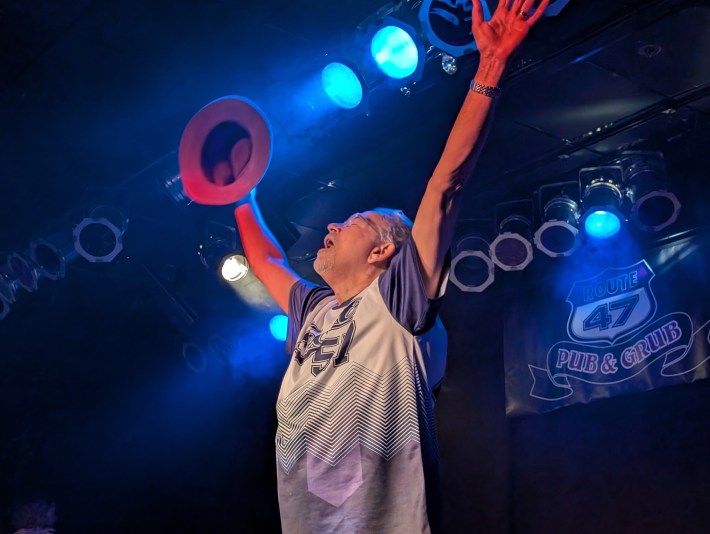

The whooping continues for AirMazon Prime, clad in an Amazon driver’s uniform and burdened with delivery boxes. “This fucking job,” he says to the crowd, setting down his load before putting a fist in the air, the universal signal that an air guitarist is ready to rock.

He fires into a self-created medley that opens with Limp Bizkit’s “Break Stuff” and ends with a jubilant leap into the crowd.

He and four others move on to perform the Beastie Boys’ “(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!).” The Iron Dragon reverse duck-walks across the stage. Shred Savage windmills in a skeleton onesie to the anthemic shouts. And AirMazon Prime leaps into the crowd again, chugging a beer from a nearby table as he keeps his left hand soloing with a Hendrix-like level of casual virtuosity.

After he’s crowned champion, AirMazon Prime, who later reveals that he actually works for Amazon, says he practices every day and has been focusing on his left-hand work.

“I've been doing this for 11 years,” he says. “When you care about it that much, and you put that much into it, you fly halfway across the country, it makes you feel good to come back with a crown, whether it’s a Burger King crown or not. It don’t matter. I feel amazing.”

It’s his first regional win. However, if he makes the international competition, it won’t be his first time flying to Oulu, Finland, where the World Championship is held annually. Years ago, he made it there through a contest after being diagnosed with lymphoma.

“Now, I’m doing it the right way,” he laughs, the crown wobbling on his head. “I’m so happy.”

Other air guitarists come by to recount parts of his set they loved with a litany of superlatives. Even in the glow of victory, he can’t talk about his win without gushing about the community.

“Heartbreaker? That’s my favorite guy in the world,” AirMazon Prime says. “I was like, ‘I’m coming to your show. I don’t care what I have to do, how much it costs.’ I wanted to support him. Winning was second on my mind.”

Maybe that was the case for others as well. Any disappointment in not taking top honors seemed to evaporate quickly after everyone was invited on stage for an en masse “Freebird” finale.

“I think air guitar just starts with the love of music,” The Lost Heartbreaker says. He has a lot of thoughts about what works and what doesn’t—don’t pick a song that panders to the crowd, “great performances tell a story”—but it boils down to loving music and being with others who feel the same way.

“I think, at its core, the best performances are when you’re coming [on stage] because you love a song and you just want to be goofy with your friends,” he says.

Inside Route 47, air guitarists are still standing around, beers in hand, reminiscing about past competitions in Washington D.C. or Cleveland, and mutual friends made in Finland. That includes people, unequivocally counted as friends, with whom they don’t share a language. But they’ve bonded anyhow, because they speak in a love of music, expressed through air guitar and maybe a fresh set of arm tassels.