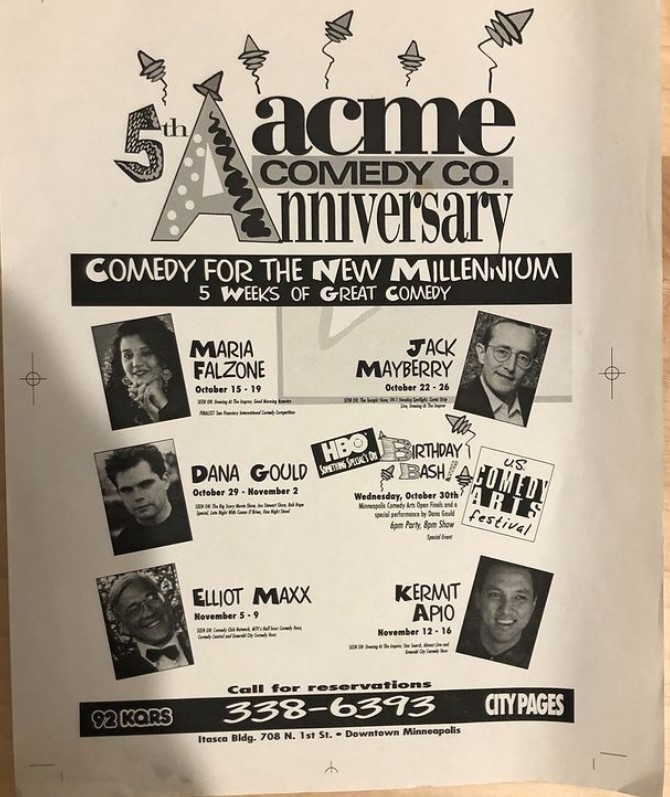

This week, Acme Comedy Co. is celebrating its 30th anniversary with 30 comics from throughout the club’s history. While it’s an accomplishment for any comedy club to survive that long, it’s even more impressive when you hear the backstory.

For the past three decades, Acme has been a cornerstone of standup comedy, not just in Minnesota, but across the country. From Mitch Hedberg to Nick Swardson to Maria Bamford, the list of comedians who cut their teeth at Acme reads like a comedy all-star lineup. The club has also been the backdrop for numerous comedy specials and network TV shows.

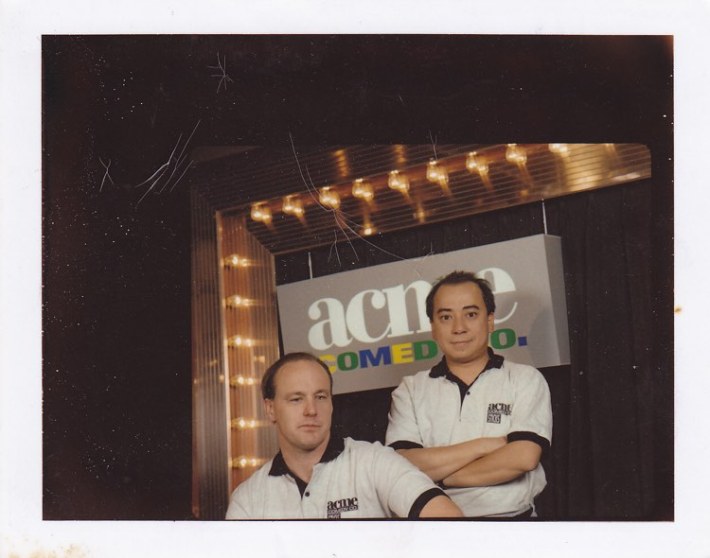

But if it had been up to owner Louis Lee, Acme might never have even existed.

In the late ’80s, Lee had been partners with Minnesota’s comedy kingpin, Scott Hansen, helping to open several major clubs in Minneapolis and St. Paul. But after Lee was in a near-fatal car accident, Hansen pushed him out of the business, leaving Lee with a mountain of debt and a sour taste toward standup comedy.

“I lost everything,” Lee recalls while sitting in Acme’s basement bar in the Itasca Building. “And when everything went to hell with Scott, my friend Jim Meyer and I said, ‘To hell with this. Let’s find a neighborhood bar.’ We were both bartenders, so we figured we could do this. Running a comedy club was the last thing I wanted.”

Lee and Meyer would end up leasing Acme after a run of other failed comedy clubs attempted to fill the space. However, the plan at that point didn’t involve comedy.

“I absolutely refused to have a comedy club,” Lee says. “Jim and I just wanted the restaurant and the bar.”

Eventually, a friend with a background in marketing convinced the partners to start hosting comedy in the showroom, offering to help hire a booker so they could stay focused on the bar and restaurant. Lee reluctantly agreed, and in 1991 Acme Comedy Co. was open for business.

Kristen Andersen-Anderson, a comic who had made a name for herself throughout Minnesota in the ‘80s, was brought on to book acts for the club. But the partnership was short-lived, as she and Lee couldn’t see eye-to-eye. (According to Andersen-Anderson, Lee only hired her to leverage her comedy contacts before pushing her out the door. Lee says that Andersen-Anderson didn’t have the connections she had claimed, and was unable to deliver on their booking agreement.) In her place, Lee hired Becky Johnson.

Johnson was married to Gary Johnson, who had won the first-ever comedy competition at Mickey Finn’s bar back in the late ‘70s, and had been a fixture of the scene ever since.

Johnson had been arranging shows for her husband throughout the Midwest, and booking acts to perform at Williams Peanut Bar. But once Scott Hansen took over Williams, Johnson was pushed out. That’s when Lee came calling.

“I was excited about it,” says Johnson. “It was a beautiful room, for starters. Louis and I talked about the comedians’ needs, his budget, and if I thought I could work with it and still present something viable.”

Johnson agreed to come aboard, on the condition that her husband would become the house emcee. Lee agreed, and for the next several years she worked tirelessly to put together the best shows she could.

“There were a few comedians who weren’t afraid to cross over [and work Acme], even though Scott Hansen discouraged it,” she recalls. “Comics like Joe Keyes and Alex Jackson and Barry Fox. I also started calling a lot of comedians out of the Seattle area that I knew of from working at Williams.”

Names like Tim Slagle (who will be a part of this week’s anniversary) and Kermet Apio would get their start at Acme around this time, along with breakout stars like Stephanie Hodge and Adam Ferrara.

“At the risk of sounding arrogant, I had a good eye for funny,” she says. “I listened to the material and not the audience reaction. I was looking for comics who were polished, professional, clever, and clean.”

Still, she says, it was an uphill battle to keep the club open.

“The first year was a struggle,” she recalls. “We gave away a ton of free tickets. That was our bread and butter. We’d do an amateur comedy contest and give every contestant 20 free tickets to pack the audience.”

Around this same time, another comedy club, Knuckleheads, would open in the Mall of America. Knuckleheads was owned by Rich Miller, who also owned comedy clubs and managed comics out of Texas.

“We knew we couldn’t do the thing where comics had to choose between one club or the other. It was bad for comedy,” Lee remembers. “Rich agreed, and we decided to work together when it came to booking features and hosting open mics so that we weren’t competing with each other.”

Miller also had the inside track on the emerging comedy scene in Austin, Texas, and soon he and Lee would begin working together to help showcase Austin comics in Minneapolis, while sending Minneapolis comics to perform in Austin.

“That was really a turning point for the whole scene,” Lee says.

Meanwhile, Johnson continued bringing in new, fresh faces to Acme, including one name that would become a legend.

“Becky booked Mitch Hedberg as a feature,” Lee recalls. “I remember watching him and thinking, ‘This guy has something, but people just hate him.’ Half the audience would leave during his set and wait in the bar until he was done.”

By 1994, the crazy hours of the club had started to wear thin on Johnson, who was also taking care of her family. Eventually she left the club in favor of a more regular schedule at a law firm in town, though she had made quite an impact before her exit.

“I would say the paying audience increased by 30 percent by the end of the first year,” she says. “We started building a really strong reputation early on, gaining recognition with the press and putting on shows that an audience could appreciate.”

When Johnson handed over the reins, Lee was still not ready to take on the role of booker. Instead, he reached out to an old friend from the past.

Jennifer Bryce (Jen Lack during her time at Acme) got her first taste of the standup comedy business years prior as the marketing director for Scott Hansen’s Comedy Gallery locations, where she would first meet Lee. After being let go by Hansen, she had no interest in getting back into comedy.

“Comedy just died,” Bryce recalls of comedy in the ‘90s. “Every bus driver bought a bar and started a weekend comedy show. I think David Brauer actually wrote a piece when Acme first opened, and the tone was basically, ‘Well, comedy is dead and some idiot is still going to open a club. So if you’re interested, you better go see a show while you can because it’s probably not going to last very long.’”

After Johnson’s exit, Lee reached out to Bryce and asked her to take over booking duties. Having had a few years away from standup, she decided to take on the challenge.

“I wanted to do it because comedy was a dead art form,” she says, bluntly. “It needed to be revived, and the comedy scene in the Twin Cities was worthwhile.”

With Bryce booking, the club continued to thrive with even more up-and-coming acts coming in from places like New York to perform in the growing comedy hub.

“We brought Kevin James in,” she remembers. “And in the mornings I would drive all the comics around to their radio gigs. He had never been to Minnesota before, and the first day, I go pick him up and there’s a snowstorm and I’m eight months pregnant. He spent the whole time panicking that we were going to crash into a snowbank and he was going to have to deliver my baby.”

Others, like Doug Stanhope and Frank Caliendo, would also make their way to Acme during Bryce’s time, too. But the real key, she says, was Lee’s mind for building the business.

“His strategies were brilliant,” she recalls. “The open stage night; attracting the college crowd. Things like that. I always thought that Louis should be doing the booking because he was brilliant, but he didn’t want to be out in front of everybody.”

Over the next couple of years, Bryce and Lee would become more connected, attending festivals and making the trek out west to scout new, emerging talent. When Bryce left the club to have a baby, Lee finally made the decision to take on the talent for the club.

“When Becky left, we started using comics who had been doing the open mic and the contest at Acme for years,” he recalls. “I also started to realize what I liked in terms of comedy. When Jen left, we tried to bring in someone else for a little while, but I knew that there was a right way to book comedy and he wasn’t doing it, so I finally took over.”

While the following years would have their ups and downs, Lee would bring in a mix of long-time club favorites like Jackie Kashian and C. Willi Myles, new talent like Chad Daniels and Pete Lee, and comedy legends like Robin Williams. But had it not been for the work of Johnson and Bryce, Lee openly admits that the club may have died off many years ago.

“Becky kept the talent coming in that first wave, and Jen played a big part in getting press and bringing in bigger names later on,” Lee says. “They helped me to really understand what was missing in comedy, and to see the difference between the real comics and the road comics.”

Though Johnson and Bryce may not have been up onstage every night, few individuals were as important as they are when it came to building Acme—and rebuilding comedy as a whole.

“Everybody said comedy was dead, and we were working our asses off to prove it wasn’t,” says Bryce. “I look at comedy as one of the most underappreciated art forms. It’s such a naked art. It’s just you and the people. Our job was to give them as much stage time as possible, pay them on time, and give credible feedback. Acme has always been a place that is great for those things.”

Related: In Memory of Twin Cities Comedy Pioneer Scott Hansen