Racket collaborated with the Bethel University Arts + Culture Reporting class to produce the stories you'll read this week. Our editors worked with students, mostly juniors and seniors, to develop ideas, source stories, and edit them for the enjoyment of readers. Feel free to seek out these young journalists, photojournalists, and graphic designers to fill your internships and jobs. They like to get paid for their work, and thanks to Racket members and a grant from Bethel, they got cashed out for these pieces. Enjoy!

Dan Flaherty logged into his office computer on March 17, 2020, to find an email from the Minnesota Health Department. It was a message he’d been dreading—and on St. Patrick's Day, too.

He was told to shut down his business immediately in order to help stop the spread of the then-novel coronavirus. And for the first time in his 30 years of managing Flaherty’s Arden Bowl in Arden Hills, a northeast Minneapolis suburb, he was forced to close his doors to the community at Snelling Avenue and County Road E. So much for luck of the Irish.

Like the other 10,492 Minnesota establishments forced to shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Flaherty’s had to figure out how to pay its bills and not lose its client base. For three months, a building usually filled with the sounds of families laughing, ‘80s classics playing, and bowling pins toppling fell silent.

Desperate to feel a sense of normalcy, Flaherty took a risk and began inviting a select number of “regular” customers to come in and bowl, free of charge, making sure to keep the amount of cars in the parking lot to a minimum in order to avoid suspicion from passersby. Along with free bowling, the fifth generation family-owned operation hosted church services in the parking lot and, later, banquet room.

“I’m sure we broke the law,” Flaherty says. “But people were just itching to get in and throw the ball.”

87 Years of Bowling History

When it comes to risk-taking, the apple doesn’t fall far from the family tree. Dan Flaherty’s grandfather, Patrick “PC” Flaherty, broke a couple of rules, too, and it led to his founding the business in 1938.

Patrick Flaherty was born in 1898 to Irish-immigrant parents Micheal and Mary Flaherty. According to family lore, Michael and Mary met on the ship from Ireland to America after discovering they had the same last name. (Don’t worry: It turns out they weren’t related; Flahertys were everywhere in Ireland, like Smiths in the U.S.) They settled in Madison, Wisconsin, and later moved to Minnesota, where Patrick Flaherty grew up and attended St. Thomas University in St. Paul.

Upon graduation, he became a vacuum cleaner salesman for Hoover. Angling to increase his sales one day, he started crossing boundaries and selling outside of his sales territory. It resulted in a meeting with his boss, and ended with him getting fired.

But Patrick Flaherty wasn’t done hustling. He saw an opportunity in the growing popularity of bowling among working-class men in the late 1930s, and like many entrepreneurs at the time, he anticipated America’s appetite for bowling.

So in 1938 he started a small six-lane bowling center in the basement of a strip mall on University & Raymond Avenues in St. Paul called Flaherty’s Recreation Center. In 1947 it became Flaherty’s 12 Beautiful Lanes and moved to Falcon Heights. After yet another move, this time to its current Arden Hills home, the alley expanded to 24 equally beautiful lanes in 1963. And according to Dan Flaherty, Flaherty’s Arden Bowl is now the longest running family-owned bowling alley (if you add up the years from each different location: 87 years) in the U.S.

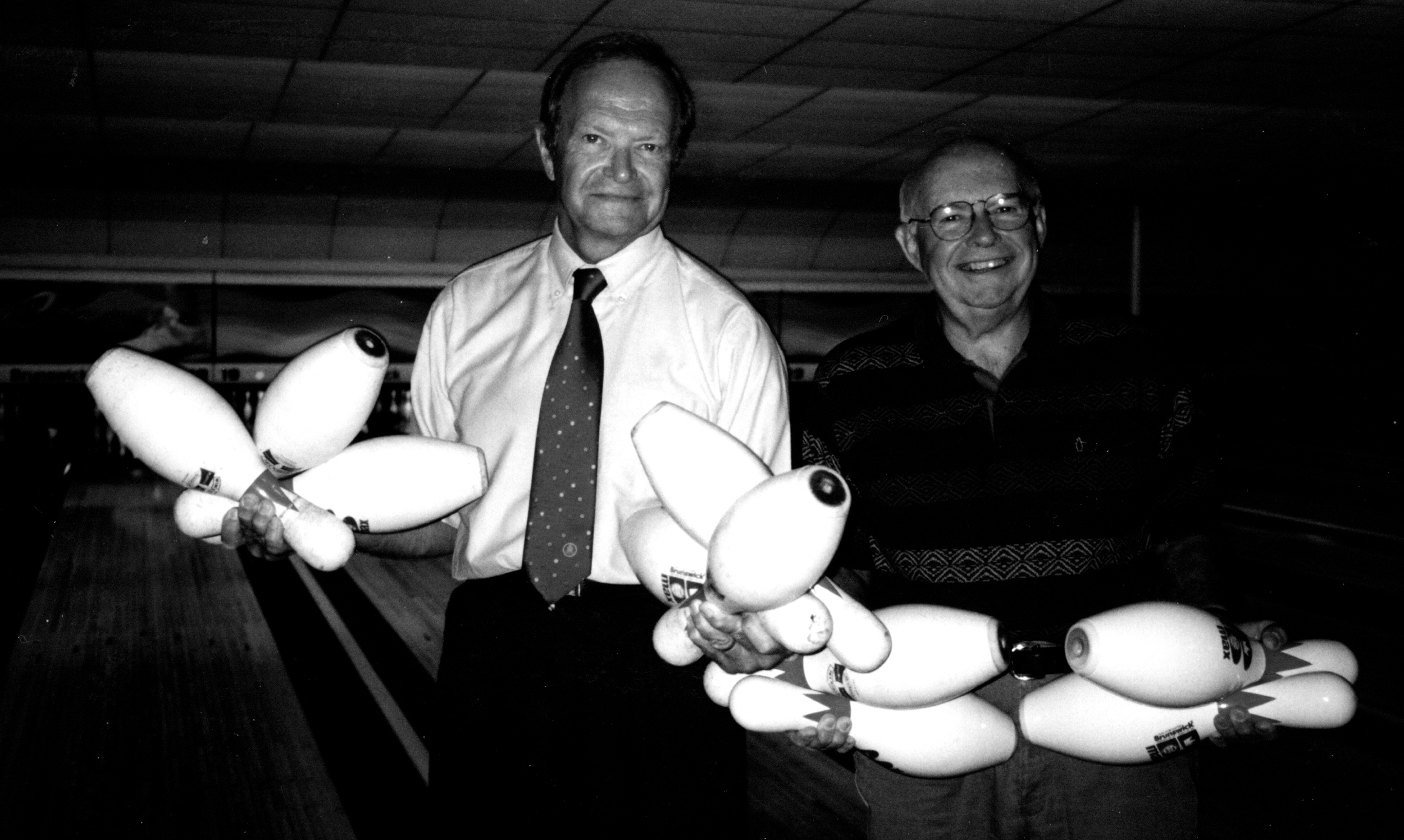

Over those decades, generations of Flaherty’s have stepped up when a previous owner stepped down. Patrick Flaherty’s sons—Patrick Flaherty Jr. and Richard Flaherty—took on the positions of part-time owners after their father’s health declined due to Alzheimer's disease. Dan Flaherty took over the position of general manager in the early ‘90s from his father Patrick Flaherty Jr., and Dan Flaherty’s son Adam Flaherty joined him in 2019. (Yes, you’ve now read the name “Flaherty” 27 times in this story.) Today, Adam’s 16-year-old daughter Bridget works the counter and cash register at the bowling alley, becoming the fifth generation Flaherty to help keep the pins clattering.

Every Night Is “One Big Party”

When Dan Flaherty’s father died in 2010, he had left the bowling alley in strong financial shape by investing money back into it every year. That shrewd stewardship allowed Flaherty’s Arden Bowl to survive the 2020 pandemic, which the family says is the closest it ever came to shutting down for good.

“We’ve survived World War II, and 9/11 was a big issue with the economy, but COVID-19 was the only time where we were shut down,” Adam says. “It was a scary, scary time, just because we have about 72 employees here and 12 full-timers who have families themselves. Our biggest concern was making sure they were able to make it on their end.”

In the months following the initial shutdown, loyal customers from the Arden Hills community started sending encouraging emails and unsolicited cards filled with money to support the business. Two forgivable loans from the federal government’s Paycheck Protection Program also provided relief, and allowed Dan Flaherty to continue paying his full-time staff members and avoid layoffs.

When COVID-19 restrictions loosened, Flaherty’s could start making money by sending staffers to customer’s homes to deliver buffalo chicken and “garbage” (sausage, pepperoni, and black and green olives) thin-crust pizzas right to people’s doorsteps.

Thanks to the pizzas, the cash-filled envelopes, and the government-funded relief checks, Flaherty’s kept the lights on, and the community thanked them for it. The year after the 2020 shutdown was reportedly the busiest-ever during Dan’s reign.

“Every night was just one big party,” he says. “$200 or $300 bills, and some guy would just cover it all.”

Dan watched as generations of returning customers walked back through the doors.

“What’s really satisfying is when you start seeing your customers' kids coming in, and then their kids,” he says. “To me, that says we’re doing something right.”

Today, the bowling alley features 36 lanes, an arcade, an indoor pub and grill, and an outdoor patio with seating and bags (or “cornhole” for you non-Midwesterners). Inside, the back wall is filled with photos of Flaherty’s evolution from 1938 to now.

“We could have easily been one of the many victims of businesses that did end up having to shut the doors,” Dan says. “I look back on it, and it was just a blessing.”

Emily Christiansen is a sophomore journalism major with a media production minor at Bethel University in St. Paul. She is usually singing or shredding chords on her 2010 Korean-made single-cut Paul Reed Smith electric guitar. She enjoys telling stories about unique and genuine people—the quirkier the better—and likes getting personal with the sources she interviews to discover the good, bad, and ugly details of each of their lives. She is a writer, social media editor, and podcaster for Bethel University's student run newspaper The Clarion. She is seeking a career in writing/reporting and broadcast journalism.