Maddie Robinson, a third-year journalism student at the University of Minnesota, started her career at The Robinson Press, where she was editor, publisher, printmaker, and reporter—all by the age of 6.

At the (sometimes inconsistently) daily newspaper, Robinson covered breaking news, including what her dad made for dinner and the coworkers her mom complained about. The enterprise was short-lived, lasting about a week. But it was emblematic of her parents’ support for her written work early on, as well as her dedication to telling stories.

At the U of M, she experiences some of the same joys from her days at The Robinson Press, while also facing some much harsher realities.

“It’s hard; it’s frustrating; it burns you out sometimes,” says Robinson, who juggles a campus job and an off-campus internship while covering arts and entertainment for The Minnesota Daily, the campus newspaper. “But I think it’s worth it.”

The state of the journalism industry looks increasingly dire as newsrooms shrink, media conglomeration proliferates and public distrust of journalists grows. This year has been a bloodbath for media layoffs and closures, prompting a recent New Yorker article to ask, "Is the media prepared for an extinction-level event?"

That parade of grim headlines hasn’t stopped more than 100 students at the University of Minnesota from pursuing journalism degrees. As a J-school student myself, I can’t help but wonder: What the hell am I thinking?

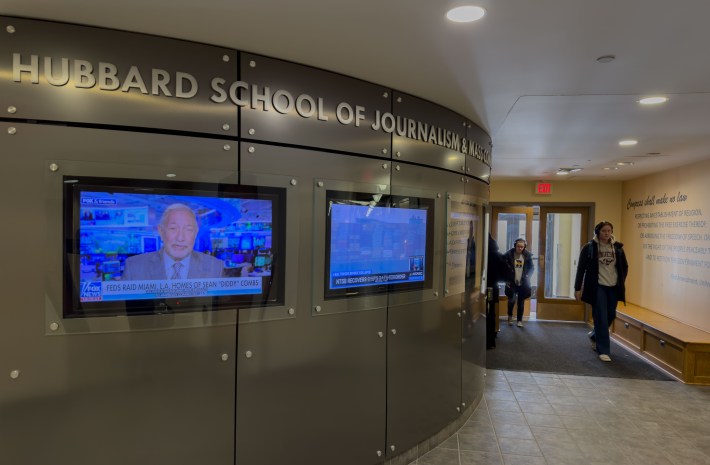

The Hubbard School of Journalism & Mass Communication, which has served as the university’s accredited journalism school since 1922, was home to about 612 students as of fall 2023, according to enrollment data. (Right-wing billionaire/media tycoon Stanley Hubbard acquired the naming rights in 2017.) Of those students, 151—about one-fourth—were undergraduate journalism majors, reflecting a historic tilt away from journalism and toward fields like public relations and marketing.

Each of the eight journalism majors I interviewed for this article expressed worries about getting jobs in the industry after graduating. But most, like me, have a reason for holding on—an inherent curiosity, a love of storytelling, meeting new people, learning new things—and continuing to pursue journalism.

Robinson, who is vice president of the university’s Society of Professional Journalists chapter, says young journalists still give her hope for the industry.

“They are all here for the same reason,” she says. “They’re here to provide fair, just reporting to tell stories of people who don’t get their stories reported on.”

Shrinking Newsrooms, Shrinking Opportunities

Robinson, who’s applying for reporting internships this summer, is still nervous about her generation’s diminishing career prospects.

Gigs in the Twin Cities are competitive. Robinson has applied for reporting internships with the Star Tribune, Minnesota Public Radio, Sahan Journal, and WCCO, and she’s in the process of applying for more. So far, she’s secured an interview at one of those outlets. She recognizes the uncertainty of the job market for journalism grads, considering how historically choppy industry waters are at the moment… and for the past several decades.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects there will be a 3% decline in the employment of news analysts, reporters, and journalists between 2022 and 2032 (including a decline of 17.6% in newspaper publishing). The news industry, including digital, print, and broadcast news, faced 1,754 job cuts this year through the end of February, according to a report by job market research firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas.

Robinson has landed more opportunities in “journalism-adjacent” jobs with transferable skills (writing, researching, critical thinking), including as a content intern for the American Academy of Neurology and in a communications position within the university. There’s a booming Facebook community, What’s Your Plan B?, that’s devoted to helping burnt out and/or laid off journalists transition to other, less troubled industries.

Lifelong love of journalism aside, Robinson may well end up taking a different career route.

“I’m just grateful for where I am now,” she says. “And wherever I go in the future, I’ll know that at least a journalism degree helped me in some way for it.”

The Allure of Strat Comm

Even within the Hubbard School, students face a choice between journalism and its sister path, strategic communications, which includes advertising and public relations—something I contended with myself, wondering if I’d be better suited entering a job market that seemed more stable.

The latter is a popular decision.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics predict that the advertising and public relations industries will see a 6% increase in employment from 2022-2032. Additionally, both fields have significantly higher average salaries: about $139,000 and $67,000, respectively, compared to the journalism industry’s average of about $56,000. According to reporting by The Guardian, the ratio of PR professionals to journalists has shifted considerably over the past 50 years. In 1980, there were 1.2 PR people for each journalist, a number that increased to four to one by 2010; in 2021, that ratio was 6.2 to 1, according to Muck Rack.

Up until fall 2019, the three majors now offered by the Hubbard School—journalism, strategic communications, and media and information—were all housed under a single major: journalism, according to Rebecca Rassier, the school’s associate director of student services. Because of that lumped major classification, enrollment data show 546 undergraduates were journalism majors in the fall 2018. Last fall, under the trifurcated system, we know at least 151 students were specifically studying journalism.

Because of the changing structure of the school, it’s not clear whether there’s been a decline in students studying journalism at the university. In fact, the school has grown over the past few years, according to Valérie Bélair-Gagnon, its director of undergraduate studies. One thing is clear: Strategic communications is on its way—if it’s not already there—to being the most popular major inside the Hubbard School of Journalism & Mass Communication. Last year, 71 students graduated with journalism degrees, according to enrollment data, compared to 185 students graduating with strat comm degrees.

Ethan Fine, a journalism major who’s set to graduate this spring, says he appreciates that the Hubbard School includes lessons on crafting messages for clients, which has helped him apply his photojournalism skills to a photography job with The Big Ten Network.

“It has helped a ton,” Fine says. “Because when you’re making content that’s primarily circulated on social media, you’re definitely trying to capture a specific moment in a specific way for a specific purpose.”

Looking to Grad School

Fine says he was sold on journalism early on. Now, as he approaches graduation, he’s applying to law schools. He’s found the news industry is simply too risky.

In high school, he participated in yearbook, newspaper, and video production classes that fostered his love for journalism. He was drawn to the industry by the prospect of meeting new people and learning something new every day.

“I’ve always been such a curious person,” Fine says. “I’ve always loved getting to just talk to people and learn what makes them tick.”

During his time at the University of Minnesota, Fine realized journalism was becoming increasingly difficult to break into; anyone with social media can post something and call it news, and it could garner the same attention as a news story. “I always try to have in the back of mind: When I’m going for a job, what’s going to set me apart?” he says.

As he approached graduation, Fine wondered if he was going to be able to put his education to use and get a steady job as a photojournalist. He determined a journalism career carried a lot of risk and little reward. Fine took the LSAT and is now applying to law schools.

“A lot of what it came down to was: Am I ready to break into the job market—not so much with the skills I have—but am I going to be able to find a job?” Fine says.

Balancing Commitments

As a reporting intern for the Hudson Star-Observer in Wisconsin, I sacrificed evenings and weekends to cover events in my community. Over the summer, I took fewer days off than I ever have because I worried about what I’d miss.

Some of those decisions I made for myself. Others, the job made for me.

Several students voiced concerns about work-life balance amid the 24/7 news cycle. Third-year journalism major Henry Stafford says they have found it difficult so far.

While working at the Minnesota Daily, Stafford would arrive home after editing sessions to see their phone continually light up with notifications instructing them to fix a story before publication. It’s a job that doesn’t sleep, Stafford observes, and working so much without adequate pay can prove disheartening.

“I enjoy it, and I want to be good at it, and be the best journalist that I can be,” Stafford says. “And to do that, you… have to put up with the bullshit and keep going.”

Alexandra DeYoe, a second-year student and reporter at the Minnesota Daily, says her responsibility to be fair and accurate leads her to the lines between work and personal time. DeYoe says she’d sacrifice her free time in favor of sharpening a story nine times out of 10.

“Mistakes are huge in this industry,” she says. “Even the smallest typo, that’s not good.”

Mistakes are likely on the rise, too. When layoffs hit, copy editors are often among the first targets—you’re seeing more typos for a reason. With depleted ranks, newsrooms are asking more and more of reporters, my harried Racket editors confirm. More beats. More stories. More self-editing. More photographs. More everything. And while 72% of journalists choose negative words like "struggling" and "chaos" to describe their industry, per a 2022 Pew study, 77% report they'd pursue a journalism career all over again.

Through a support system of coworkers and a community of student journalists, DeYoe has been able to manage the stresses of work-life balance.

“I think the best thing journalists can do for each other is just be open about what they’re going through,” DeYoe says. “And be authentic and honest about it… It’s going to be shit sometimes.”

Starting Something New

Anna Belden, a fifth-year journalism student, reports she’s also worried about the long hours of TV news. After committing to her major, several guest speakers have told her about the hard work-life balance in broadcasting, especially as a cub reporter. Now she questions whether it makes sense to enter such a demanding field right after graduation. “You can’t really know what you’re getting into until you’re fully into it,” Belden says.

Carly Berglund, Belden’s classmate, plans to graduate in the spring and start her career as a multimedia journalist for a Minnesota broadcast station. She shares many of the same concerns, but she’s excited to start her new career by giving people in her community a platform.

Echoing the sentiments of many of the other students I spoke with, Berglund says her decision to enter a collapsing industry isn’t all that tough: “I really cannot imagine doing anything else.”