During the heyday of U.S. trade unionism, United Steel Corp. didn’t have beliefs. Ford Motor Co. wasn’t mission-driven. Contemporary corporate buzzwords like “values,” “mindfulness,” and “intentionality” didn’t matter to industrial manufacturers, their largely unionized workforces, or their customers who simply wanted reliable beer cans, combustible coal, and fail-proof jet engines.

But today’s economy is unrecognizable from that of the 1950s, when U.S. labor last flexed considerable muscle before a decades-long downfall spurred by political kneecapping, internal mismanagement, and widescale deindustrialization. Today, as unionization rates hover near all-time lows, glimmers of hope for labor are appearing in traditionally non-unionized sectors—food/beverage, digital media, retail, museums, nonprofits, and tech. Bucking historical norms, those industries are public-facing, with customers who are often barraged by messaging about what companies believe. But when that rhetorical rubber meets the labor-agitated road, corporations often default to the same anti-union tactics that they’ve employed for more than a century.

“The public—even people that aren’t plugged into unions—have enough common sense to see hypocrisy from companies when it happens,” says Hamilton Nolan, a national labor reporter for In These Times. “If you’re unionizing the cement plant, it’s harder to lean on that element of hypocrisy. In these cases, with these companies that have public progressive branding… they’ve always been the low-hanging fruit in terms of targets for organizing. Because you have that extra amount of leverage—their back is more against the wall, because they’ve said all this bullshit already.”

In the Twin Cities, we’ve witnessed this phenomenon with increasing frequency over the past five years. Outwardly progressive shops like Surly Brewing, Half Price Books, Tattersall Distilling, Minnesota Historical Society, Peace Coffee, Planned Parenthood North Central States, Spyhouse Coffee, and Science Museum of Minnesota have all refused to voluntarily recognize their unionizing workers and, in some cases, drew allegations of outright union-busting. Ditto for local outposts of massive chains like Starbucks and Trader Joe’s. And then there’s Common Roots, the ultra-progressive Minneapolis café that closed last week days after its owner, Danny Schwartzman, agreed to recognize its union.

Schwartzman professes to be pro-labor and says his business represents a case study in the potential, as well as the shortcomings, of unionizing mom ‘n’ pop restaurants. Market dynamics and worker empowerment collided last month at Common Roots, resulting in mixed emotions over the ethically minded restaurant’s demise.

“If you’re buying a latte or choosing the next book you want to read, you are interacting with the people who are providing that service to you,” says Peter Rachleff, a former Macalester College labor professor and co-founder of the East Side Freedom Library. “We’re mostly seeing younger workers, and in many cases workers with higher education backgrounds. And they may even have been drawn to their employer because of the employer’s professing of progressive values. That has the possibility of inspiring, insighting, and provoking.”

How We Got Here

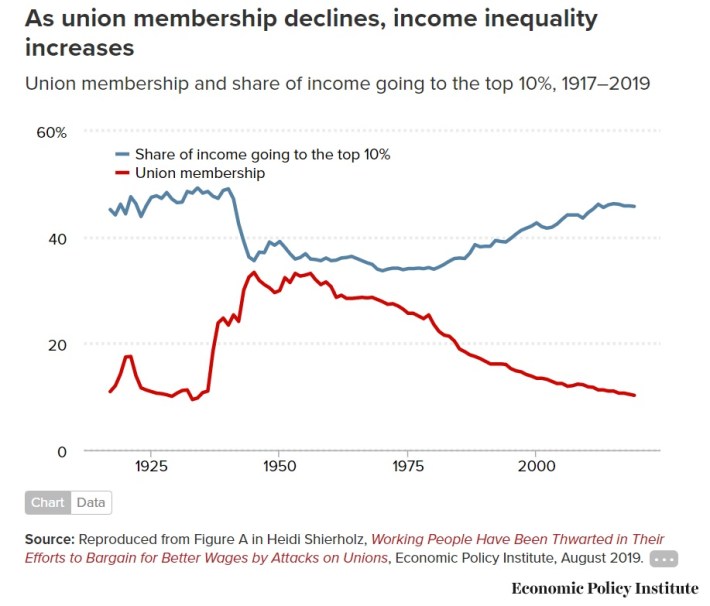

In the middle of the 20th century, about a third of U.S. workers belonged to unions. By 2000, that number had plummeted to below 15%. Last year it hit 10.3%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, though Minnesota boasts a higher-than-average union representation rate of 15.8%. The culprits are numerous: Reagan, NAFTA, right-to-work laws, stigmas of corruption and/or outdatedness, not to mention a 40-year bipartisan political consensus to rally around pro-biz interests. Leftists have a favorite chart that depicts the economic ramifications of dwindling worker power:

Around 2019, Unite Here Local 17, the local chapter of the hospitality union that represents around 300,000 North American workers, began strategically organizing the labor-neglected Twin Cities food and beverage scene.

“We had the goal of organizing in hospitality areas that we had not organized in for a long time,” secretary-treasurer Sheigh Freeberg told us in 2020. “But we felt like there was an opportunity there. Honestly, every time something happens, I have a dozen other places reach out to me; it’s super exciting. Coronavirus happened, and workers didn’t have the opportunity to pretend their boss cared anymore, because their bosses made it so incredibly clear that they didn’t.”

That excitement has been met with fierce opposition from business owners. Of the roughly half-dozen craft beverage shops organized by Unite Here Local 17 in recent years, only Fair State Brewing Cooperative has secured a first contract, and its union was voluntarily recognized. That resistance from management is more or less the norm, according to Bloomberg Law: Ratifying first contracts for new unions takes an average of 465 days. And, in some cases, union drives get squashed well before anyone arrives at the bargaining table. (More on that below.)

“It’s historically been a hard sector to unionize, because of the high turnover and tenuous workforce,” says Nolan of In These Times. “We’re going to see more of it. It’s going to take workers who are really, really committed enough to see it through.”

COVID-19 catalyzed union activity in a number of industries, including museums like the Minnesota Historical Society and Science Museum of Minnesota. The same is true for local locations of powerhouses like Starbucks and Trader Joe’s as well as major nonprofits like Planned Parenthood. All of this came at a time when unions are viewed with historic favorability, according to Gallup polling, while anti-corporate views form a rare bridge between both major political parties, per Pew. (Important caveat: Small businesses are viewed with overwhelming favorability.)

“Upsetting, confusing, and frustrating” behavior from Half Price Books management during COVID-19, including layoffs that “lacked transparency,” amplified existing employee grievances, HPB worker David Gutsche told us in late 2021. Planned Parenthood North Central States workers, who voted overwhelmingly to unionize in July, say their company froze merit pay during the pandemic, even as their clinics’ services became more essential than ever following the repeal of Roe v. Wade.

You hear similar sentiments from just about any organizing worker post 2020, especially the Minnesota teachers and nurses who powered through strikes as COVID-19 made their essential jobs untenable.

“It’s really important that we open our ears, and our hearts, to stories coming from rank-and-file workers themselves,” Rachleff says. “There are all kinds of company brands, logos, and self-representations, and then there’s the reality people experience when they’re actually working.”

Messaging vs. Actions

Surly Brewing Co. positions itself as a benevolent, boozy force woven into the fabric of Minnesota culture. “Because living in Minnesota rules, we give back to our community,” reads copy from its charitable arm, Surly Gives a Damn.

In the summer of 2020, two days after 100+ Surly workers went public with their union, the country’s 34th largest craft brewer announced mass layoffs and the impending closure of its beer hall. It blamed the pandemic. (PPP loans are an important factor to consider with any corporate pandemic-blaming; companies from big—Surly, $2.8 million—to small—Common Roots, $537,000—collected forgivable loans from the federal government intended to keep workers on payroll.)

“We anticipated some behavior on Surly’s part to discourage the union, so when [the layoffs] happened, that’s the first thing we thought of,” Surly worker Megan Caswell told us that fall. “This is clearly their attempt to fire us all and reopen with a new staff that’s not unionized. Personally, I still kind of feel that way.”

By that October, workers secured a union election overseen by the NLRB: 56 voted yes and 20 voted no. But the union push failed to gain a majority by a single vote because 36 workers abstained.

"You’ll find Surly on menus, shelves, and tap lines,” the company promised customers in a press release announcing the failed union vote. “We’ll be out there giving a damn.”

Caswell was apparently right. After closing its Minneapolis beerplex in November 2020, Surly reopened the following June with a mostly new staff.

On its website, Tattersall Distilling details the ethical, carbon-friendly sourcing of its ingredients and barrels at great length. In the fall of 2021, ex-worker Mike Appletoft didn't sound impressed with his old company, which still holds the distinction of being the nation’s first unionized craft distillery. “It’s become a very toxic workplace,” he told us. “Management took out their frustration and anger over [unionization] on us.” Appletoft alleges that Tattersall's move to a 75,000-square-foot “destination distillery” in River Falls, Wisconsin, was a deliberate move to undermine the union. Speaking via email with two PR professionals CC’ed, Tattersall co-founder Jon Kreidler denied any anti-busting allegations.

The stated Mission & Values of Starbucks read like a flowery, new-age manifesto. Early last year, unionizing Minneapolis barista Kasey Copeland used it as ammo against the 35,000-location multinational coffee giant.

“We are a little nervous about the union-busting tactics Starbucks has been employing, but that doesn’t add up to their mission and values,” she told us at the time. “They don’t scare us.”

Recently, New York Times readers got a deep-dive look into the anti-union mind of Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz. “He prefers to see himself as a generous boss, not a boss who is forced to treat employees generously,” write Noam Scheiber and Julie Creswell in “Why Is Howard Schultz Taking This So Personally?”

“With the exceptions of Elon Musk and Donald Trump, most bosses want to look in the mirror and think they see a decent human being staring back out at them,” Rachleff says. “So they want to tell a story that depicts them as decent and socially minded.”

Over 300 U.S. Starbucks locations have attempted to unionize, resulting in 262 victories. In Minnesota, nine have tried—six wins, one loss, one withdrawal, and one still open. Workers continue to push back against Schultz’s paternalism. “We make all of their profits for them. We have all of the power in this situation,” Copeland told us in August during a one-day strike timed to the release of pumpkin spice coffees.

Over at the museums, boss vs. worker relations don’t appear much better.

The Science Museum of Minnesota Workers' Union issued a petition in November to fight back against management.

“Museum management has hired a union-busting law firm and launched an aggressive anti-union campaign,” they wrote. “The museum claims to value equity and collective liberation—now it's time to live those values.”

Last month, Minnesota Historical Society workers felt compelled to go public with news of their frustrating, stagnating bargaining sessions. (MNHS CEO Kent Whitworth claims the two sides “have made significant progress.")

“Like with a lot of other nonprofits, you get this message as an employee that you’re so fortunate to have this job, the mission is so important, nobody should be asking for more than the bare minimum,” union president Molly Jessup told Racket. “But we do believe we deserve more than the bare minimum. As an employee you want to know that you are valued and respected, and we certainly haven’t always felt that way in negotiations. We’re not seeing a spirit of collaboration.”

Neither is the team at Trader Joe’s on Washington Avenue in downtown Minneapolis, the county’s second unionized TJ’s. Worker Sarah Beth Ryther alleges the company is deliberately dragging out contract negotiations, and is forcing local workers to travel by plane to Hadley, Massachusetts, to negotiate in-person; TJ’s brass shot down proposed video bargaining. Ryther doesn’t think her employer’s actions meet the high bar set by CEO Dan Bane’s “7 Golden Rules.” (In ’20, Bane labeled union efforts inside his store a “distraction.”) Washington Avenue workers staged what they hoped would be a 30-minute walkout on New Year’s Eve. Management didn't let them back in until the store had closed.

“Personally, I bought into what Trader Joe’s was selling when I was first hired,” Ryther says. “I really, really, really did... I know that gaslighting is a buzzword right now, but we are told day in and day out that this is an amazing place to work, we care so much about you, and then, in terms of their actions, it’s exactly the opposite.”

Neither Rachleff or Nolan are surprised to hear that companies with do-gooder branding turn less friendly when they’re challenged by labor.

“They don’t want to give up money, but they ultimately will give up money before they give up power. And unions are asking for power,” Nolan says. “It’s really the single best test of any progressive company. The fact that a lot of these companies don’t live up to it… it’s not surprising. It’s just revealing that those values were bullshit in the first place.”

There’s seemingly no limit to the potential divide between rhetoric and reality in the world of progressive brands. Consider No Evil Foods, the “socialist” faux-meat company that retaliates against its union. Or Amy’s Kitchen, the organic food maker that violates the rights of its. You might expect a company with brand messaging like “We’re starry-eyed dreamers who believe in bicycle-power, being nice, and bringing neighbors, farmers, and the community together” to happily recognize its workers’ union, but you’d be wrong in the case of Minneapolis-based Peace Coffee. “Peace Coffee does amazing things for the community, it’s time for us as employees to be treated with the same care and respect,” roaster Jade Hampton said last spring, two months before his colleagues won their union election.

Contemplating Common Roots

Which brings us to Common Roots, the most recent and perhaps most complicated example of unionizing within a progressive company. It’s hard to question the values that undergirded the café at 2558 Lyndale Ave. S. for 15 years: living wages and benefits, paid sick time, urban gardens, majority local and sustainable buying practices.

Then, suddenly, it all vanished.

Common Roots kitchen lead Audra Johnson had prepared soup for the next day’s lunch service on December 28. Hours later, owner Danny Schwartzman announced that the café would immediately close for good. There’d be no soup—or anything else—on the 29th, a fact the 30-person staff discovered 30 minutes before the general public. Complicating matters, around 20 of those staffers had informed Schwartzman of their intent to unionize with Unite Here Local 17 one week earlier.

Before any union involvement, Johnson says employees came directly to Schwartzman with several grievances, including poor communication that could lead to confused, last-second scheduling. Those concerns went unaddressed and seemed, to employees, to frustrate their boss, leading to a series of one-on-one meetings in which two workers were eventually fired. Schwartzman initially expressed excitement for the union, Johnson reports, saying he just needed to talk to a lawyer to smooth things out. He eventually voluntarily recognized it, which sparked plans for a celebration. Days later, he announced the closure.

“It’s weird,” says Johnson, who started working at Common Roots in August. “[Schwartzman] probably ended up being buried in all these thoughts of failure, and he just called it quits. He had a lot on his plate, and we all know that. But we thought [unionizing] would be a way to organize that mess that he had to deal with, and make it more workable for everyone.”

Schwartzman released his statement about the closing last Wednesday; the aspirational union workers released theirs shortly thereafter. As promised, workers received checks for their unused PTO earlier this week. Schwartzman tells Racket he was genuinely excited about running a union Common Roots, adding that it might be a boon to business. More pressingly, he says, sales remained half of what they were pre-pandemic.

“Obviously I didn’t close my 15 years of business in a rash bowing out because of a union,” he says, noting that the tight timeline Unite Here Local 17 demanded for a response caught him off guard. “Honestly, the added strain of going through a union negotiation was a relatively insignificant part of my concern about the next six months to a year. It certainly forced me to stare with open eyes at the magnitude of challenges we were already facing.”

Schwartzman describes himself as a lifelong supporter of the labor movement, though he says that movement “just came at the wrong time” to his small business. Johnson liked her lefty workplace, and confirmed that its lofty principles were not bullshit. At the messy intersection of business and beliefs, however, sometimes hard numbers and harder realities dictate the course.

“I think, personally, [Schwartzman] believed [in a unionized Common Roots],” Johnson says. “But I think as a business owner, he overruled his own beliefs.”