In 2006, the Science Museum of Minnesota played host to the highly popular--and highly controversial--“Body Worlds,” an exhibit featuring real, human corpses that have been donated to science and plasticized.

The museum consulted with religious officials and medical ethicists beforehand, but that didn’t temper concerns people had for the exhibit, and the public’s reaction hovered somewhere between fascination and disgust. These are not just hyper-realistic statues, after all. They’re actually people.

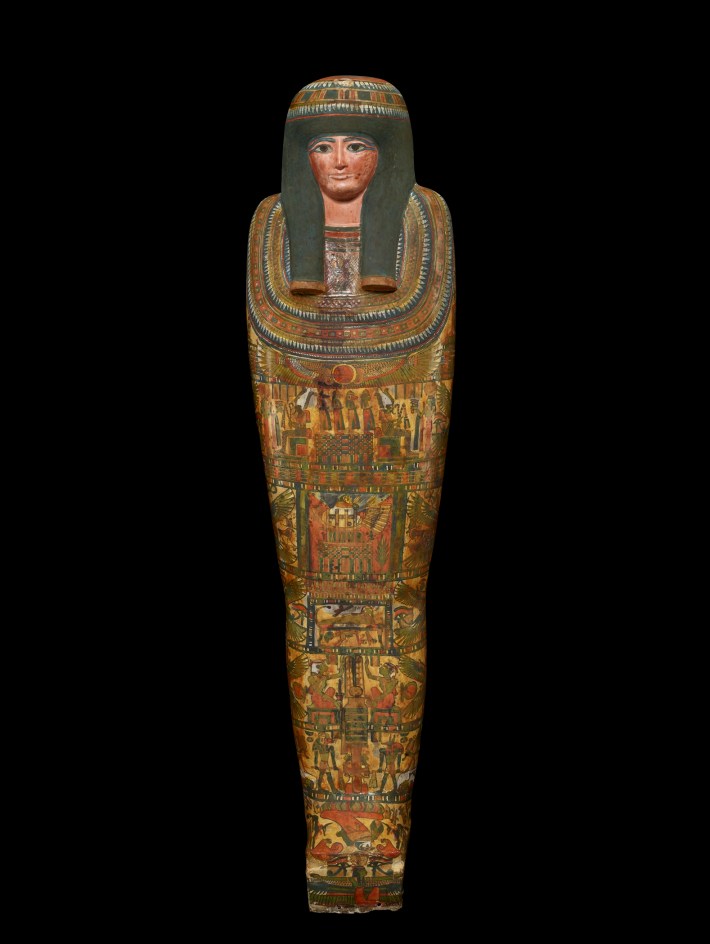

But while hundreds of thousands of Minnesotan visitors were looking on in fascination, awe, and muted horror, they may have forgotten that another dead person has been present in the museum for decades, long before “Body Worlds” ever showed up. Just around the corner, tucked into its own private display case, was the museum’s resident Egyptian mummy. He has been here in Minnesota longer than most of us have been alive. In fact, he has been here almost as long as the museum itself.

In 1925, a museum trustee named Simon Crosby found him for sale in Cairo; a remnant, the antiquities dealer assured Crosby, of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. That would be in the time of King Tut, whose tomb had only just been discovered in the Valley of the Kings. The white, western world was mesmerized by images of gilded sarcophagi and lavish treasures, but also morbidly fascinated by rumors of ghoulish-looking corpses and ancient curses.

“In particular, [Crosby] was thinking--as a lot of people at that time were--that you’re not really a museum unless you have an Egyptian mummy,” current-day curator of anthropology Ed Fleming explains. The Science Museum, which was still building its fledgling collection, was eager to play host to this one.

For decades, that’s all anyone knew about the dead person upstairs. He came with no credentials. No context. Nobody could say where he’d been buried or when. Nobody even knew he was a “him” at the time (subsequent x-rays and CT scans would later indicate that the mummy was, as anatomy and convention would dictate such things, male).

Gradually, technology was able to tell us more. The mummy died in his 30s or 40s (a pretty ripe age at the time) with calloused feet and soft, delicate hands. He walked without shoes but didn’t labor. He had fine, healthy teeth. What he lacked in precious talismans he made up for in a coating of luxurious pine resin, which would have been imported. His head was shaven; the typical mark of a priest or a civil servant.

He was not from the 18th Dynasty. Carbon dating from a bit of rib placed him back 2,000 years ago, in the Greco-Roman era. Think “Cleopatra” rather than “Tut.” The earlier designation had been either a mistake or a complete fabrication.

But he was authentic, which was a relief, because there was a distinct possibility that he might not have turned out to be an ancient Egyptian mummy at all. Collectors have fallen for alleged mummies that have turned out to be, as one Field Museum curator put it in 2016, “KFC bones and sand,” and--most upsettingly!--far more contemporary dead people.

It’s impossible to know what the mummy would have thought of his future lodgings while he was alive, but few people probably confess a desire to become a curiosity for strangers after death. Even the folks who donated their remains to “Body Worlds” may not have done so willingly, as there have been some troubling allegations to the contrary, though it’s impossible to know for certain.

Like many artifacts of the non-European world, mummies have been massively appropriated, misunderstood, and plundered. And they still are, to some extent. The fact that each of these exhibits represents a life--to say nothing of centuries’ worth of cultural heritage--has only recently dawned on the western museological and academic community as relevant, let alone troubling.

For the record, Egypt has always been fairly clear on that point. An article, titled “‘Return Mummies and End Curse!’ Egypt Begs World,” appeared in the Star Tribune in May of 1930, and it reads like it could have been written yesterday: “Egypt has begun a movement for the return of hundreds of mummies of its ancient kings, queens, and high priests under the slogan: ‘Give us back our dead!’”

The unnamed priest isn’t the only Egyptian mummy resting in the Twin Cities. Mia has three. One, a teenager named Lady Tashat, remains on display--though not visible--in her cartonnage in the museum’s African collection, though it’s not specifically mentioned in the description that Lady Tashat is still in there. It’s possible some patrons have never realized as much. Another two mummies reside in storage.

“We don’t really think about ancient Egyptian mummies as human remains whose exhibition in museums is problematic,” says Jan-Lodewijk Grootaers, Mia’s art of global Africa chair and curator. “Maybe we should do that a little more, but that’s not in our culture.”

Egyptian mummies, he points out, are far more remote from their survivors than other artifacts owned by the museum. In particular, Mia is in possession of an Australian Aboriginal tjurunga made of stone. Tjurunga are supposed to contain the spirit of an ancestor. It is, in essence, another stolen body… which is why Aboriginal communities have been continuously agitating for the return of sacred objects like these from museums all over the world. Grootaers is currently corresponding with Shaun Angeles Penangke, the cultural repatriation manager of the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory in Australia, about Mia’s resident tjurunga.

The Science Museum of Minnesota reached out to the Egyptian Embassy in the mid-‘90s. Fleming says that at the time, there wasn’t any interest from the Egyptian government to have this particular mummy returned. As for displaying him, the embassy gave its approval--as long as it was done respectfully.

Today, you can find the mummy resting behind an alcove in the human body annex on the second floor. A sign placed nearby warns patrons they’re approaching real human remains. There are displays explaining the process of mummification and its spiritual significance. X-rays show us the bones broken to retrieve the brain, and that the heart was carefully returned to the mummy’s chest cavity.

Another sign inside the alcove displays a letter from a museum patron, dated 1996. It’s surprisingly frank:

“I certainly do believe that it is immoral, unethical to have the body of a human being lain there, without its consent, like furniture on display for your visitors to look at and ponder… Please, let me know what you think of this, because I made up my mind to stand up on behalf of this woman, because she was one of my ancestors.”

Displayed next to it is a response from Don Pohlman, the director of anthropology at the time, detailing the “inconclusive efforts by museum staff” to explore the return of the mummy to Egypt, and a promise to take these concerns seriously and carefully examine the issue.

But for now, he rests in his display case, partially unwrapped, fractionally understood, prompting more questions than answers, refusing to condemn or comfort the viewer.

If there is one thing that connects all of us to an ancient Egyptian mummy, it’s that one day, each and every one of us will die (foreshadowing!). And it will be up to others to decide if there is anything to learn from what remains.