The Velvet Underground is John Cale’s reward for making the inspired career choice of outliving Lou Reed. Many voices, alive and dead, including Reed’s curt Long Island snarl on occasion, contribute their perspectives and remembrances and gripes to Todd Haynes’s richly archival, ingeniously edited two-hour documentary, but Cale’s assured Welsh purr is the predominant baseline thrum throughout. If the film has a hero, it’s Cale.

He’s the first figure we see, pre-Velvets, a conservatory longhair straight from central casting, performing Erik Satie’s “Vexations” on piano for the game show I’ve Got a Secret as host and panel react so snidely they could make you want to sell military secrets to the Soviets. Square America could then comfortably guffaw at such egghead bunk, but once its affectations were smuggled into pop the olds would secretly fret that their kids knew something they didn’t. The Velvet Underground is less the story of how the collision of Cale’s high-art drone and Reed’s stark rock poetry abetted that cultural change and more about about the art world that made that collision possible, if not inevitable.

The band doesn’t even enter the studio to record its 1967 debut until halfway through Haynes’s two-hour documentary, and as the filmmaker tells it, it’s kinda all downhill from there. The film imagines the Velvet Underground as a moment in time, an outgrowth of the New York experimental arts scene of the ’60s. This was a world shaped by filmmakers like Jonas Mekas, who filmed the band’s first performance, impresarios like the Velvets’ rabbi, Andy Warhol, and musical boundary-pushers like drone pioneer La Monte Young. And there was rock 'n' roll, another soup can on the shelf waiting for cultural transformation.

Who can say if Haynes would have told the story differently had Reed not died in 2013, and really, who cares? To his credit, Haynes would rather be provocative than definitive. Too many music documentaries (too many documentaries in general) waste their runtime making an excuse for their existence, with familiar faces testifying to their subject’s significance. But this is a 200 level Velvets seminar at the least, assuming all your prerequisites have been met. No Eno quote about how the few people bought the first album all started bands. No rock critics offering potted histories. No fucking Bono.

Anyway, to center on the historical argument of The Velvet Underground is ignore the visual poetics that are more powerful than its thesis, which is often the case with Haynes’s idiosyncratic readings of rock history. Velvet Goldmine, his faux Bowie biopic, was essentially glam fanfic, its make-your-Ken-dolls smooch approach a revisionist response to his frustration that pop wasn’t as queer physically as it was aesthetically. His celebrated, prismatic Dylan pic I’m Not There bugs the shit out of me: If too much Dylanology already focuses more on his iconography than his music, Haynes just multiplied the problem by casting six actors as Bob. But he literalized the lyrics so impressively that I was cowed into admiring it in 2007, and only on my second viewing years later did I feel free to say how much was not there.

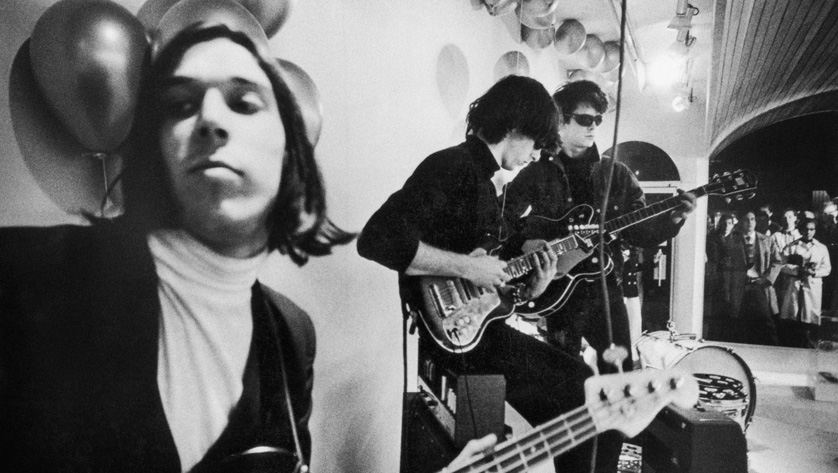

Haynes works in split screen here, and even when there’s just one image displayed about a quarter of the screen is a dark box. No one gets to command the full filmic rectangle. He's an expert at inhabiting a past style to reimagine it, and this doc is to Warhol’s Chelsea Girls as Haynes’s Far From Heaven is to Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows. Haynes has the Reed and Warhol archives to draw from, including Warhol’s fabled screen tests, where he filmed Factory habitués or visitors alike doing as little as possible. Seeing separate black and white films of Reed and Cale side by side, self-consciously staring at us, illustrates the dialectic of their working relationship more profoundly than any voice over; dousing the screen in multiple shifting images suggests the sensory overload of the Velvet Underground’s multimedia performances. And this is a band that existed to be photographed, their style an essential part of their substance, even more so when Warhol foisted a gorgeously tragic Teutonic ice-crystal formation called Nico on the band as their singer. I’d love to have heard more about where they got their clothes and who cut their hair.

For all its avant presentation, Haynes still relies on talking heads to connect the narrative dots, and for once women are fairly represented. Acerbic drummer Maureen Tucker is still around. Martha Morrison represents her late husband Sterling, and Reed’s sister Merrill Reed Weiner protests that the story of his post-college shock therapy has been sensationalized. “The Factory was not a good place to be a woman,” film critic Amy Taubin tells us. Warhol “superstar” Mary Woronov, as ever in a VU doc, badmouths hippies.

Standing in is for generations of admirers is the eternally effervescent Jonathan Richman, guitar on lap, who claims he saw the band more than 70 times. If only all fanboys were such close listeners—his discussion of the phantom overtones he could hear in the band’s music that didn't come from any specific instrument is especially sharp. “These people would understand me,” he recalls thinking at his first VU show, and it’s heartwarming to hear how these bristly, cranked-up Manhattan scenesters were inexplicably kind to this no doubt annoying-as-hell high school kid who obsessed over them. Richman also points out how many Deadheads were into the Velvets, which suggests that plenty of those west coasters heard something in the band that eluded Warhol’s parochial clique.

Reed remains an enigma throughout. We get perspectives on him, many backhandedly condescending. “He was like a three-year-old,” a friend recalls. “He was talented beyond his talent,” says another. “I couldn’t do anything to please him,” Cale laments solemnly. And sure, he was an asshole, that’s unanimous, but assholes are like opinions—no two are exactly alike. At the center of the film is the silhouette of a caustic, grinding cipher with the wrong sort of ambition for his scene pals. And as some early discussions of Reed’s frequenting gay bars and fascination with S&M taper off, so does much of the film’s interest in sex.

Instead, we get Cale enthusing of Warhol’s Factory “It was all about work,” which does succinctly get at the essence of the band’s aesthetic. Not for nothing were amphetamines their drug of choice. And if the Velvets were experimental, it was with a clinical rigor that distinguished them from the let-it-rip school of psychedelia, which fluttered away with faith that moments of serendipity would occur. What preserved their experiments from the possibility of grim austerity was Reed’s pop craft.

While offering a corrective to the myth of Lou Reed as singular genius, Haynes slights the third act of the Velvets story. Once Reed makes his Cale-or-me ultimatum to Tucker and Morrison, who chose correctly, and nice guy Doug Yule helps the Velvets become a working group that busts its collective ass for recognition, the film seems to side with Warhol aide Joseph Friedman, who laments, “Then they were like a regular rock 'n' roll band.”

Like hell they were. Maybe a regular rock 'n' roll band had Loaded in them (I said maybe) but not The Velvet Underground. Haynes’s focus on the (admittedly more cinematic) Warhol years leads even a smart guy like the Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw to weirdly opine “Maybe no subject more fits the phrase ‘you had to be there’” about a band whose fans were notoriously weren’t there, whose fame blossomed after they broke up.

What those fans had, after all, were the records. They could stare at the banana on the cover of The Velvet Underground and Nico or images of the dark-shaded hipsters in the band, but all they really had were sounds. Talking about a band’s “influence” is often just a cheap way to indicate a band’s greatness without making the effort to describe it. But in this instance, it's a way of indicating that far from marking a moment, the Velvet Underground proved an inexhaustible source of inspiration for different musicians who could hear what they needed to in those recordings.

That influence is so widely disseminated now that it’s encoded in bands who’d never cop to it. And it’s just plain boring to talk about. Perhaps more interestingly, the Velvets and Warhol established a template for scene after scene across America. In college towns and smaller cities, fine arts theorists would latch on to someone who could play guitar to make their pretensions sexier, more immediate, more fun to dance to.

While visually disruptive, the narrative of The Velvet Underground is pat. The ’60s were a long time ago, and the survivors interviewed here take a circled-wagon approach to their legacy. I was grateful whenever Danny Fields, the heroic Elektra A&R guy and publicist who’d later manage the Ramones, brought the Exploding Plastic Inevitable down-to-earth by complaining about how Warhol would “flash these fucking polka dots” on the band. Or when Haynes couldn’t resist the second most famous quote ever about the group, Cher’s “It will replace nothing, except maybe suicide.” (God, I’d have loved to have heard her and Reed go at each other at some point.)

If there’s something absent here, it’s rancor. Which is maybe to say, "If there's something absent here, it's Lou." Still, Todd Haynes has done us the incredible service of creating a great film that comes nowhere close to offering the final word on The Velvet Underground. There’s still plenty to argue about more than 50 years later. Your turn, I guess.

The Velvet Underground opens today at the Lagoon in Minneapolis. It's also streaming on Apple+.

Special Screenings This Week

Friday, Oct. 15

Ginger Snaps (2000)

Trylon

Darling this is no joke. This is lycanthropy. $8. Friday 7 p.m. Saturday 9:15 p.m. Sunday 3 p.m. More info here.

Jennifer’s Body (2009)

Trylon

Before Megan Fox became, uh, the First Lady of punk or something, the Morticia to Machine Gun Kelly’s Lurch starred in the revisionist horror flick turned cult classic, written by local-gal-made-good Diablo Cody. $8. Friday 9:15 p.m. Saturday 7 p.m. Sunday 5:15 p.m. More info here.

Saturday Oct. 16

The Craft (1996)

Alamo Drafthouse

A classic of careful-what-you-witch-for teen magic-dabbling, with four Catholic school outcasts getting all spooky with the deviltry. $10. 6:30 p.m. More info here.

Teen Wolf (1985)

Parkway Theater

Ain’t no rule says a werewolf can’t play basketball. $5-$10. 1 p.m. More info here.

People Will Theater Again: A Short Film Showcase

Trylon

Films include Bathroom Break, Blueberry, Good Enough, Mani Come Ragni (Hands Like Spiders), Mickey Hardaway, and White Tears. $16. A benefit for Texas Equal Access Fund, Planned Parenthood, and Yellowhammer Fund. 3 p.m. More info here.

Sunday, Oct. 17

Beetlejuice (1988)

Alamo Drafthouse

What the hell happened to you, Tim Burton? $10. 3:45 p.m. More info here.

Them! (1954)

Trylon

Nuclear testing creates man-eating ants so big they get their own exclamation point. $8. Sunday 7:30 p.m 7 p.m. Monday; 9 p.m. Tuesday. More info here.

Monday, Oct. 18

Slugs: The Movie (1988)

Trylon

A movie about slugs that hurt you. And we’re not talking punches in the arm! $8. Monday 9 p.m.; Tuesday 7 p.m. More info here.

Wednesday, Oct. 20

Dr. Alien (1989)

Trylon

She’s not a real doctor, but she is a real alien. $5. 7 p.m. More info here.

Opening This Week

Halloween Kills

What’s the deal with this Michael Myers guy anyway? I hope we finally get some answers.

Hard Luck Love Song

A movie based on a Todd Snider song, huh? Haven’t seen it but I can say that Snider is aces.

The Last Duel

The angels did say/Was to certain poor shepherds in fields where they lay.

The Rescue

A documentary about those divers who rescued that kids’ soccer team in Thailand from a flooded cave. The trailer gave me a panic attack.

Ongoing in Local Theaters

The Addams Family 2

Candyman

Dear Evan Hansen

The Eyes of Tammy Faye

Free Guy

I’m Your Man

Lamb

The Man Saints of Newark (read our review here)

No Time to Die (read our review here)

Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings

Titane (read our review here)

Venom: Let There Be Carnage