It's a sunny Saturday, and about a hundred people have gathered in the upstairs meeting room of the Walker Church in south Minneapolis for a chatty, amiable Pizza Luce lunch. Young and old mingle; a toddler darts between people’s legs. When the food is gone, the assembled group folds up the tables, pushes them to the edge of the room, and gathers their chairs in a circle for an afternoon class on direct action.

“The cops know where the cameras are and where they’re not,” the organizer leading the class tells the group.

On January 26, a loud, contentious Minneapolis City Council meeting ended with a 7-6 vote to demolish the Roof Depot site in the East Phillips. The Roof Depot is an abandoned warehouse that sits at the heart of the “arsenic triangle,” a highly polluted sector abutting East Phillips and Little Earth. Local residents have uniformly rejected any new construction there, insisting that the city return ownership of the site to the community. Instead, the city plans to redevelop the site by knocking down the warehouse and creating a public works campus that will centralize equipment and trucking.

In response, the East Phillips and Little Earth neighborhoods are organizing.

“We’ve always been prepared for this eventuality,” says CJ, an organizer with Climate Justice Minnesota. Climate Justice is one of the organizing groups supporting Defend the Depot, the group that put on the training at the church. The community is opposing the demolition, and skeptical of the administration’s plans for the site, according to CJ.

“The city weaponizes the misconception that local activists are ‘outside white people,’ and that East Phillips wants this,” they continue. East Phillips has one of the lowest white populations of neighborhoods in the Twin Cities, with the highest concentration of Indigenous and Black people in the metro area.

Other classes put on by Defend the Depot included street medical care, tech security, and a Know Your Rights primer.

“We put these classes on so people could know their options when demolition time comes,” says CJ. Meetings like these have been happening roughly once a month since October 2022; that September, the Minneapolis City Council had voted to seek proposals for demolition of the warehouse.

Kelly, a trainer who led one of the organizing classes, sat on the floor and rested in between sessions. “It’s not what people want, it’s not what the neighborhood wants,” they explain. “[The city is] taking away resources from the neighborhood. They are not passively hurting people, they are actively hurting people. They are missing an opportunity to benefit the community in revolutionary ways, but they said no.”

The Roof Depot warehouse was designated a Superfund site in 2007 due to a deposit of arsenic in the soil, left over from pesticide manufacturing in the area. Residents worry that demolition will release that pollution into the air, with the city’s plans for a public works campus and diesel truck storage further compounding generations of health problems that plague the area.

The asthma rate for residents of East Phillips and Little Earth is two-to-four times greater than that of the broader Twin Cities metro area. East Phillips and Little Earth have historically experienced some of the worst air quality in Minneapolis. Attendees at the United Methodist training attribute this to decades of city neglect, the persistent pollution in the soil underneath the Roof Depot site, and presence of the Smith Foundry and Bituminous Roadways along 28th Street.

“What happens here affects Fond du Lac, it affects all of Minnesota, it goes deeper,” says Taysha, an Indigenous rights activist and Fond du Lac band member who spoke in one of the classes. “These conversations often don’t leave the room. I came down here because I believe Little Earth matters.”

“We’re not considered people,” they continue. “We’re considered activists. And if we take action, then we’re terrorists.”

Steve Sandberg and Karen Clark, decades-long residents of the neighborhood, sat in on classes. Both are board members at East Phillips Neighborhood Institute (EPNI) an organizing group trying to block the demolition and turn the Roof Depot site into a mixed-use redevelopment and urban farm. Sandberg was frustrated by the years of abuse city bureaucracy had inflicted on the neighborhood.

“What the city is doing to the Roof Depot is a metaphor for what the city is doing to the community, leaving it neglected,” he says. “And it’s textbook how they keep disparities in the neighborhood.”

“We have to deal with bullies, whether they’re the mayor or otherwise,” Clark adds. “We’ll be here ‘til the end.”

Clark represented East Phillips, Little Earth, and much of south Minneapolis in the Minnesota House of Representatives for decades. Remembering a series of meetings that EPNI had with city officials in 2022, she described the city’s fixation on the Roof Depot and unwillingness to listen to community members.

At one of these meetings, according to Clark, Margaret Anderson Kelliher, Minneapolis’s director of public works, said, point blank, “This is city land and we’ll do what we want.”

“I was disappointed, I thought Margaret was a breath of fresh air,” she says. For Clark and Sandberg, the anger and frustration are compounded by the fact that the city’s own public works department proposed an alternative site for their campus, obviating the need to demolish the Roof Depot. The report was published in June 2021, well before the city council voted on the Roof Depot demolition. It discusses the Water Yard, an existing public works facility in the Marcy Holmes neighborhood, and proposes that renovating and expanding this site instead of the Roof Depot would be a better option for the city and residents of both neighborhoods.

“It appears that the reuse of the two historic buildings and the reconstruction of the main building would be consistent with the [Marcy Holmes] Neighborhood Association’s Master Plan. The existing Water Yard operations also has a good relationship with its Marcy Holmes neighbors,” the report reads.

“In contrast, the East Phillips Neighborhood has opposed the Hiawatha campus expansion project at the Roof Depot site since the City’s purchase of that property was first proposed in 1991.”

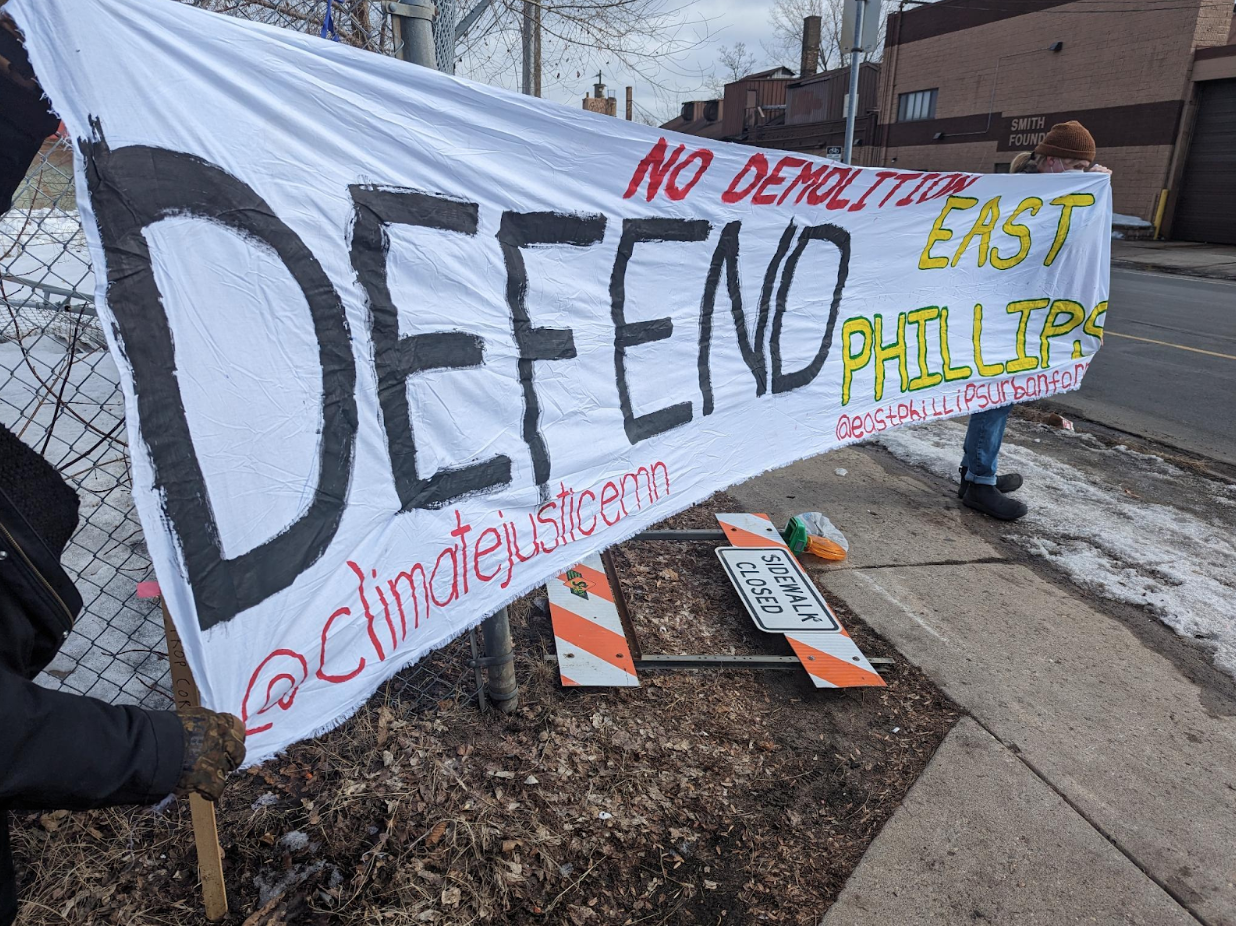

The next day, a sunny and slushy Sunday, a few hundred people gather in protest outside the Roof Depot site on Longfellow Avenue, a visible swell from the previous day. Attendees at the direct action training dot the crowd. People pass out flyers exhorting people to call Rachel Contracting, the firm that won the contract to demolish the Roof Depot, and convince them to stop the project. Speakers drew parallels between the Roof Depot and protests in Atlanta against the proposed “cop city” in Weelaunee Forest.

“They don’t give a fuck about us!” shouts one speaker. “Jacob Frey doesn’t give a fuck about us! At least seven members of the city council don’t give a fuck about us!”

“This cultural genocide has been going on for over 500 years of colonization,” adds Rachel Thunder, an Indigenous rights activist and organizer of Leonard Peltier’s Walk to Justice who lives in East Phillips. “We’re going to stop this, not just for our generation, but generations to come.”

Among calls of “We protect us!” and “When East Phillips is under attack what do we do? Stand up! Fight back!” protestors march from the corner of Longfellow and 28th to the Roof Depot front entrance. They carry signs reading “Land Back,” “Cultural Genocide Stops Here,” and “Protect the Children.”

“We will be here all week!” an organizer shouts.

And they are. Early Tuesday morning, a call went out. At dawn, protesters began moving into the Roof Depot. They are occupying the site, with a list of demands that include calling off the demolition, relocating the public works project, handing over control of the site to the community, and removing Smith Foundry and Bituminous Roadways.

The city has stated that demolition is slated to begin February 27. But among protestors, conventional wisdom says that government movement could happen at any moment. What happens between then and now is anyone’s guess. In a press release announcing the action, protestors occupying the Roof Depot decried the demolition as another in the city’s history of neglect against Black, Indigenous, and BIPOC residents.

Back at the United Methodist training on Saturday, Kelly stares in contemplation at the ceiling.

“They know what the community wants. They know we’re going to show up. We know they care enough about their property to show up armed. They are okay with violence.”

Correction: A previous version of this story inconclusively claimed East Phillips and Little Earth experienced "by far the worst" air pollution in the Twin Cities. The language has been updated to reflect that they have been historically polluted.