Josh Biber of The Minnesota Historian explored the lost lakes of Minneapolis here.

St. Paul Takes Shape

During the last ice age, most of Minnesota was covered by an enormous glacial ice sheet. The pressure of the ice cut into the land, leaving behind icy deposits that eventually melted and formed kettle lakes, such as St. Paul's Lake Phalen and Lake Como. As the glaciers melted, water surged away and carved deep and wide gorges where the present day Minnesota and Mississippi rivers meet between the bluffs.

Anthropologists date the first human history in the area to about roughly 1,500 to 2,000 years ago. The Hopewell Native Americans were the first to inhabit the region for its plentiful resources, and they chose a high bluff east of present day downtown St. Paul for their burial mounds. That sacred place exists today inside Indian Mounds Regional Park, reminding us of the diverse people and cultures that flourished in St. Paul long before Euro-American settlers arrived in the 1800s.

The land to the east of the Mississippi River fell into the hands of the U.S. in 1787 with the expansion of the Northwest Territory. All land to the west of the Mississippi quickly followed suit in 1803 via the Louisiana Purchase. In 1805, the Mdewakanton Dakota transferred 100,000 acres of land to the U.S. government through Pike's Purchase. This land was used to establish Fort Snelling as a military outpost to protect the territory from a potential British invasion via the Mississippi River to the north. By 1837, the U.S. government annexed even more land from the Mdewakanton and other Native American tribes throughout Minnesota in a series of unfair treaties in 1837.

The first settlement by Euro-American immigrants in St. Paul occurred in 1838 when two men claimed a bend in the Mississippi River about four miles downstream from Bdote, where the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers converge. The first settler, known as Pierre "Pig's Eye" Parrant, was a French fur trader who opened a saloon that welcomed Native Americans, trappers, and traders passing through the area. The second settler opened a nearby farmstead on a bluff overlooking the river valley. By the early 1840s, a few dozen settlers erected homesteads along a single dirt road next to the saloon.

The villagers first adopted the name Pig's Eye as homage to Parrant... until the Catholics arrived. The missionary assigned to open a chapel convinced the villagers that St. Paul was a more stately name. The villagers agreed, and St. Paul became the formal name. Today, you can still find Parrant's namesake in the form of Pig's Eye Lake to the southeast of downtown St. Paul. The pirate-like pioneer also lives on through the booze he once peddled.

Not much was to be said about St. Paul until about 1847, the first year a survey of the town site was conducted. Later that same year, the territory of Minnesota formed a governing body with the arrival of Gov. Alexander Ramsey. With the organization of the government, between 1860 and 1885, St. Paul's population blossomed from 10,000 to 120,000. With the massive growth of the city came industry, factories, brownstone apartment buildings, dwellings, opulent houses, a downtown core, churches, schools, and colleges. (Maybe the Catholics were right?) On Christmas Day 1886, a Saint Paul Globe article touted that St. Paul was becoming "one of the most handsome and solidest looking cities in the United States. Evidence of prosperity are apparent on every street--in fact, in every block—and strangers who come here invariably pronounce it the wonder of the nineteenth century."

St. Paul had all the tools in its civic tool belt to be a successful major city in the U.S. The City Beautiful movement took, leading to a series of beautification projects and extensive public services. However, just like Minneapolis to the west, not all lakes were treated equally. Lake Como and Lake Phalen were turned into gorgeous parks while other lakes were wiped from the city’s landscape during the peaks years of industry and development. These lost lakes of St. Paul had the misfortune of standing in the way of real estate investors and industry moguls. Over the years they were drained, filled, and mostly forgotten.

The Lakes of St. Anthony Park: Langford Lake and Partridge Pond

Langford Park and College Park in the St. Anthony Park neighborhood of St. Paul were once home to two small bodies of water before the encroachment of civilization in the latter half of the 1800s. Langford Lake was first mapped as Rocky Lake—a 10-acre lake that was part of the former Bridal Veil Creek watershed. Partridge Pond was a smaller two-acre body of water that once inhabited the present area of College Park, just beside the University of Minnesota’s St. Paul campus.

This area was relatively unbothered by human interference until the 1880s. In 1862, the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad built a new rail line connecting Minneapolis to St. Paul. The land surrounding this freshly laid track quickly became a hot commodity for real estate investors hoping to strike it rich by platting bedroom communities between the two downtowns.

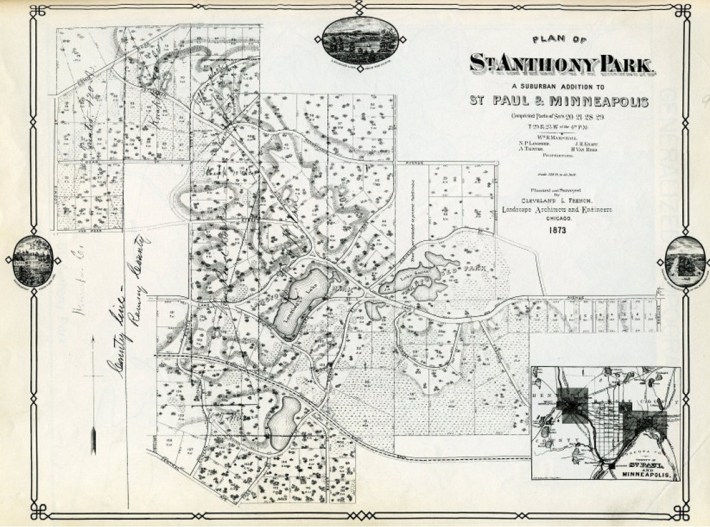

In 1872, Gov. William Marshall purchased a large swath of land that he planned to develop as the interurban neighborhood christened as St. Anthony Park. Marshall retained the assistance of famed landscape architect Horace W. S. Cleveland and his partner, William M. R. French, to map and plan a maze of winding streets and oddly shaped lots to conform with the topography of rolling hills and swampy terrain in the area. Notably, the original plans for St. Anthony Park called to keep Langford Lake and Partridge Pond as scenic water features for the neighborhood.

For the first few years, settlement was slow in St. Anthony Park. Before the age of automobiles, it was a relatively isolated community, which dissuaded many potential residents from purchasing lots. To better link his up-'n'-coming neighborhood to the adjacent downtowns, Marshall encouraged the two railroad companies to build passenger depots. In the 1880s, the Great Northern Railroad and Northern Pacific Railroad heeded the governor's requests. Surprisingly, the two depots still exist to this day; both have been relocated and converted into homes—one at 1048 Everett Ct., one at 2107 Commonwealth Ave.

With the arrival of passenger rail service, St. Anthony Park quickly burst on the scene as a bustling neighborhood on the outskirts of St. Paul. As more citizens began to move into the neighborhood, it quickly became apparent that Langford Lake and Partridge Pond were causing issues. Dozens of homes were built and streets were graded, inhibiting the Langford Lake from flowing into the Bridal Veil Creek watershed. Thus, it soon became a stagnant body of water, ripe with mosquitoes and black flies in summer months. Similarly, Partridge Pond's increasingly eutrophic water was soon choked by algae and weeds. Many nearby neighbors began to fear that fever and other sickness would originate from these stagnant waters.

To combat these alleged sanitary issues, city engineer Joseph Sewell first called for Partridge Pond to be filled for “reasons of sanitation." In 1885, the St. Anthony Park Co. drained and filled Partridge Pond; the former pond was repurposed as College Park, a small meadow lined with trees. Today, College Park's meadow still serves as a low basin for the surrounding watershed to pool into. During the spring months, Partridge Pond often appears again as snowmelt and runoff fills the shallow basin.

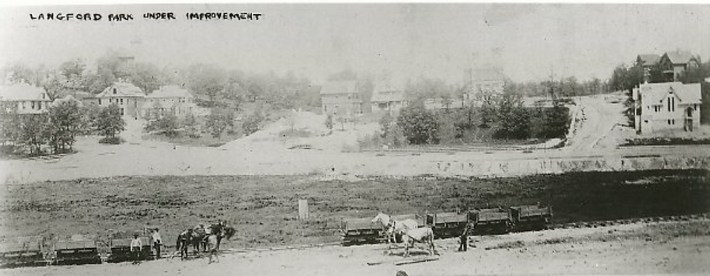

The St. Anthony Park Co. next turned their attention to Langford Lake. The process to drain and fill this deeper, larger lake proved to be a much more difficult task. The company enlisted the assistance of several mule-drawn wagons to take dirt from nearby hills and empty lots to fill Langford Lake. Early residents of St. Anthony Park recounted that the mules frequently sank into the peaty soil from the lakebed. As you can imagine, neighborhood children would gather in droves to watch the muleteers attempt to rescue their beasts from the oozing mud.

Ultimately, the primitive methods used to fill Langford Lake proved too much for the St. Anthony Park Co. The project was abandoned after roughly six acres of the lake had been filled. Langford Lake remained in its half-filled state until Horace W. S. Cleveland came back into the picture in 1888. The city of St. Paul had hired Cleveland to consult with the park board and “prepare designs and plans for the improvement of St. Paul parks and parkways” as well as to “supervise the execution of all work on parks and parkways.” In Cleveland’s new role, he encouraged St. Paul park commissioners to develop more city parks and squares by filling low-lying swampy areas by using soil from adjacent higher ground.

Thus, Langford Lake’s future became uncertain once again after residents in St. Anthony Park signed a letter to the city park board requesting that improvements be made to the reclaimed land surrounding the lake. In 1898, while under the supervision of park board Superintendent Frederick W. Nussbaumer, excavation projects attempted to restore the deteriorated Langford Lake while turning the surrounding land into a new park. Nussbaumer had different views than Cleveland. Nussbaumer felt that with the appropriate facilities and improvements, he could tame Langford Lake into a park commodity rather than eliminating it from the landscape. Nussbaumer’s park board employees excavated the remains of Langford Lake to a depth of three feet while a pipe was installed in the basin to keep water circulating. More improvements came in 1899 in the form of rip-rap along the lakeshore and the construction of a small footbridge across the narrowest portion of the lake. The surrounding land was converted into a park as trees were planted, a bandstand was constructed, and other park features were unveiled.

Nussbaumer’s improvements to Langford Lake and the surrounding park were a positive addition to the neighborhood until 1912, when St. Anthony Park was retrofitted with a sewer system. Despite the best efforts by the park board to maintain the depth of Langford Lake, the sewer system was running it dry. Nussbaumer recommended that the lakebed be cemented and “preserved even if only for the purpose of winter skating for the children of the neighborhood.”

After years of water retention issues at Langford Lake, Superintendent Nussbaumer’s wishes were finally met in 1927 when Langford was fully converted into an artificial lake. The lake was drained, a new concrete basin was poured, and water was pumped back into the concrete lakebed. Langford Lake continued its existence as a faux-lake until its ultimate demise occurred in 1953 with the construction of the St. Anthony Park Elementary School. The concrete-lined pool of water that held the remains of Langford Lake was leveled and filled during the construction of the school.

Lake Sarita

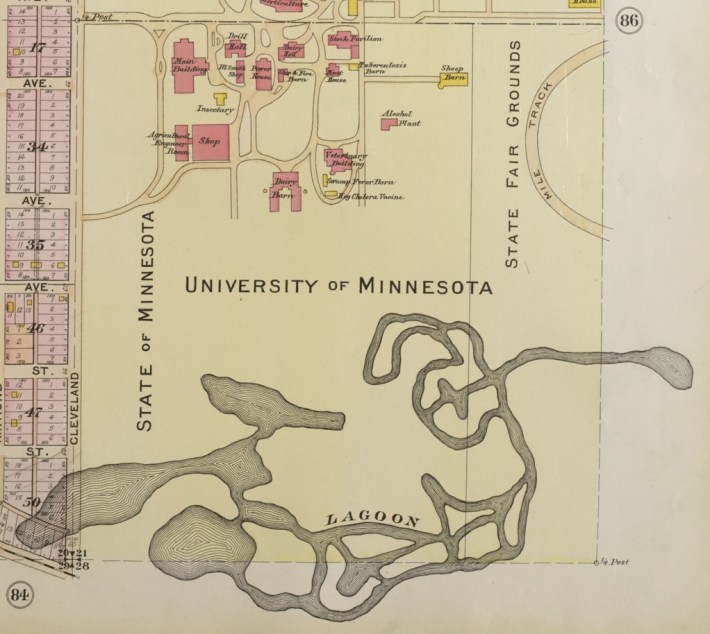

Not far from Langford Lake—about a half mile to the east—was Lake Sarita, a shallow but relatively large lake that was encompassed by a boggy landscape. Lake Sarita still exists as a small drainage basin tucked away behind the Minnesota State Fairgrounds, although the majority of it has been leveled and filled for the development of a housing cooperative on the western portion of the old lakebed and the State Fair Midway on the eastern portion.

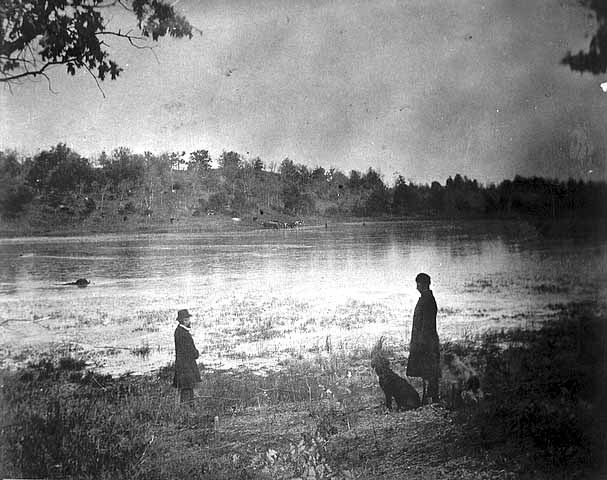

Like Lake Langford and Partridge Pond, Lake Sarita was relatively unbothered until the encroachment of Euro-American civilization in the latter half of the 19th century. When the University of Minnesota’s St. Paul campus opened in 1882, Lake Sarita became a gathering place for students looking for fun. Stories recount tug-of-war tournaments that took place beside the lake. These tournaments were rowdy affairs as scores of students found themselves covered in mud and muck after being pulled into the lake. The lake was also commonly used as a hunting ground for ducks and blackbirds.

Lake Sarita found itself in the newspapers in the summer of 1912 when Arthur Johnson, a neighborhood boy, drowned there. Arthur was swimming with two friends when they waded out to a deep portion of the lake. The boy wasn’t a good swimmer and began to panic and claw at his friends when he realized he couldn’t touch the bottom. Arthur's friends attempted to save him, but he continued to panic as he sank under the surface of the water. The friends ran to the nearest intersection and flagged down the first adults they could find. Two employees from the University of Minnesota’s St. Paul Campus— Dean of the College of Agriculture Albert F. Woods and Dr. W. L. Boyd—were on a walk when they came across the panicked children. Arthur’s friends told the adults about what had happened as the four hurried back to the lagoon.

Dean Woods and Dr. Boyd attempted to locate Arthur’s body as they waded from shore using a log to steady themselves in the water. Just as the two Good Samaritans waded to the location that Arthur went under, the log rolled over, sending Woods and Boyd into the water. Woods was unable to swim; he narrowly escaped drowning as he clambered to get a hold of the log. The two boys and Dr. Boyd reeled the exhausted Woods back to the shore. Arthur’s body was recovered later that day as news spread of the boy’s drowning.

The year after Johnson’s drowning, the land surrounding the lake was leased by the State Fair. Hoping to turn Lake Sarita into a new attraction for fairgoers, officials order that the lake be dredged and reshaped into a maze of canals extending from the present location of the Midway westward toward Cleveland Avenue. Outfitted with venetian-stylized gondolas and gondoliers, this new attraction was touted to rival the canals of Venice. However, time unveiled a different fate for the canals at Lake Sarita. The reshaping of the lake caused significant water retention issues. After a few years, the canals filled with sediment as the attraction became impassable and ultimately closed. The eastern portion of the Lake Sarita canal system was filled in and reclaimed to form the Midway at the State Fair.

For the next 50 years, the remains of Lake Sarita were encroached on all sides. The University of Minnesota’s heating plant was built on the northern portion of the lakebed, the U of M Transitway and Midway were built atop the lake’s eastern banks, and the Commonwealth Terrace Cooperative was built on the western portion of the lakebed. Today, what’s left of Lake Sarita remains as a tiny storm-water pond wedged between the State Fairgrounds and the Commonwealth Terrace Cooperative. The remnants of the lake have seen a resurgence in biodiversity over the last several years as flora and fauna have once again returned.

Cozy Lake and the Lake Como Northwest Arm

Cozy Lake was once a modest body of water that jutted out from the former northwestern arm of Lake Como. It was separated from Lake Como by a small isthmus that was removed in the late 1800s to connect the two lakes via a small channel. The lake was about five feet at its deepest, and featured a small island called Cozy Island. The land surrounding Cozy Lake consisted of oak groves and rolling bluffs. Prior to the incorporation of the city of St. Paul, Cozy Lake and Lake Como were frequently visited by the Dakota and Ojibwe peoples as they utilized two trails that skirted the shores.

During the first half of the 1800s, the U.S. government enacted several unfair treaties between the Dakota that ultimately ceded their lands and forced thousands of Native Americans to relocate to a reservation further west along the Minnesota River. Of these many treaties, a 1837 treaty opened up the land of St. Paul, and by extension the Cozy Lake area, to Euro-Americans. Over the next several decades, the once uninhabited land in the vicinity of Cozy Lake was settled by farmers and utilized by logging companies that mostly desecrated the surrounding oak groves.

By the 1870s, the city limits of St. Paul encroached the eastern shores of Lake Como. Farmers began to sell their land to real estate investors as the area soon became more urban than rural. Meanwhile, Horace W. S. Cleveland persuaded the city to purchase 240 acres of land on the western side of Lake Como to preserve as parkland, including Cozy Lake and its surroundings.

However, Cozy Lake was already running into trouble. Paired with a few years of drought and the lowering of the water table from human interference, Cozy Lake and the shallow northwest arm of Lake Como ran the risk of going dry. St. Paul’s park board attempted to repair the damage by installing a water pumping system, which kept both bodies of water filled.

Cozy Lake’s resurgence was short-lived. In 1905, a Japanese garden was unveiled on the northern shore of Cozy Lake and a bridge was built to span the channel between Cozy Lake and Lake Como. The Japanese garden didn’t last long, as fluctuating water levels damaged the new attraction. After a few dicey years on the shores of Cozy Lake, the Japanese garden was relocated to its current location beside the Marjorie McNeely Conservatory.

By the early 1920s, St. Paul’s park board had given up. Water level at Cozy Lake and Lake Como’s northwest arm had been an ongoing problem for the city for nearly three decades; the city annually pumped more than 500 million gallons of water into the two lakes to keep them from drying. In 1922, the city made the decision to dam the muddy swamp that had become Cozy Lake from the neighboring Lake Como. Within a year, Cozy Lake was wiped from the map as the lakebed went dry. Similarly, the city allowed the northwest arm of Lake Como to go dry as well; the land was reclaimed as Lexington Parkway and a portion of the Como Golf Course. Much like Sandy Lake in Minneapolis, the dried lakebed of Cozy Lake was converted into a golf course. The only hints left of Cozy Lake today are a few water hazards at Como Golf Course and its clubhouse, Cozy’s Pub.

Maplewood’s Sandy Lake

Sitting just outside St. Paul’s city limits near the intersection of Rice Street and Roselawn Avenue in Maplewood lies the lakebed of the former Sandy Lake. This lake’s departure from the landscape was recent enough that some residents still remember fishing and boating there.

Sandy Lake’s demise was long considered. In 1890, a Saint Paul Globe article read:

“A scheme is on foot for the draining of Sandy Lake, near the northeast city limits. It is intended to plat the land, after being drained, into lots for manufacturing sites. The idea is to drain off the water through the sewer which is being constructed on Harrison street. George R. Nimmons and Thomas Lowry are the men principally interested in the scheme. Should the water be drained off, a tract of land covering about 300 acres would be bared, which would be valuable for manufacturing purposes, as the Soo Road passes close to the spot. It is probable that arrangements will be set on foot at once for the accomplishment of the design.”

Nimmons and Lowry’s plans never materialized. However, Sandy Lake’s fate was sealed through a series of events starting in the late 1930s. That's when the St. Paul Water Utility was given the go-ahead to dump sediment and other waste into Sandy Lake from the McCarrons Lake water treatment facility.

By the late 1970s, new advancements in water management systems resolved the need to dump spent lime and other wastes into Sandy Lake. However, as a result of the previous three decades of sediment and waste dumping, the lake was sick and past the point of rehabilitation. The Sandy Lake's south bay had long since been converted into a series of surface lagoons to store unnaturally green- and cyan-tinted water. By the 1980s, the former lake’s north bay was filled with several feet of soil with the hopes to later develop the former lakebed.

Recently, the filled lakebed of Sandy Lake has turned into a dump site for the St. Paul Regional Water Services. It's there that the infamously nicknamed “Mount Sandy” continues to grow, with debris piling up from major pipe replacement projects.

Aurora Park Lake

In the Summit-University neighborhood, century-old homes share the blocks with churches and brownstone residences. Fuller Avenue runs through this old neighborhood of St. Paul, without the slightest hint of a small lake that once occupied the intersection of Fuller and St. Albans avenues.

Early maps of the 1860s and 1870s show this area was once a collection of shallow wetlands. As the tide of development marched further westward from the downtown core of St. Paul, the elimination of Aurora Park Lake was planned.

Sometime in the 1880s, the lake was filled to make way for Fuller Avenue. Just a few years later, in 1895, a minor league baseball ground known as Aurora Park was erected on the former lakebed. The ballpark only served St. Paul for a few years as the nearby neighborhood residents obtained an injunction, thus restricting the new minor league team from playing at the park on Sundays. In 1897, the team relocated to Lexington Park, a new ballpark that opened about a mile to the west where Sunday games were allowed.

The lake was remembered in a 1911 article in the St. Paul Dispatch that stated that this, “fine lake rested in a hollow between Central Avenue West and Aurora Avenue, extending from a half block east of St. Albans to a little west of Grotto, and was put out of existence by grading Fuller through it and St. Albans and Grotto across it.” Its site was posthumously given the name of Aurora Park Lake, after the ballpark that was once there.

Rifle Park Pond

Rifle Park Pond shows on maps as early as the 1870s. This pond was roughly the size of a city block. In 1899, a four-year-old boy by the name of Conrad Kohn drowned there. Kohn and another neighborhood boy were catching minnows when Conrad waded too deep into the water. He never resurfaced. By the 1940s, the pond was filled as the land was repurposed for a new school and running track at the corner of Earl Street & Third Street East in eastern St. Paul.

Other Lost Bodies of Water in St. Paul

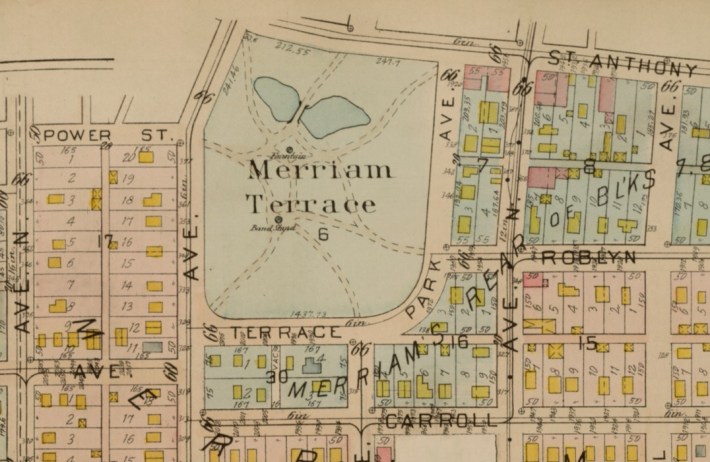

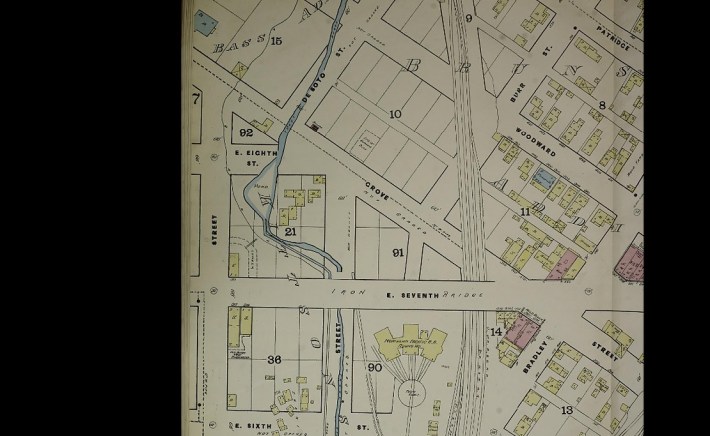

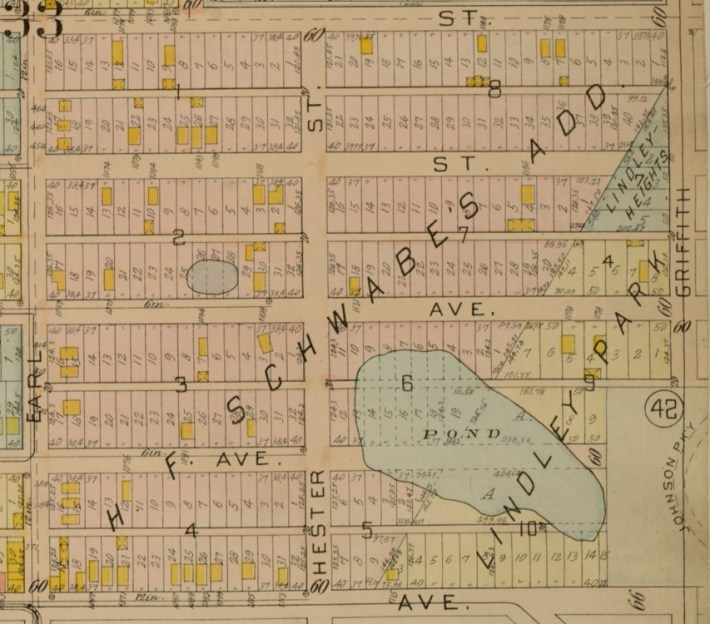

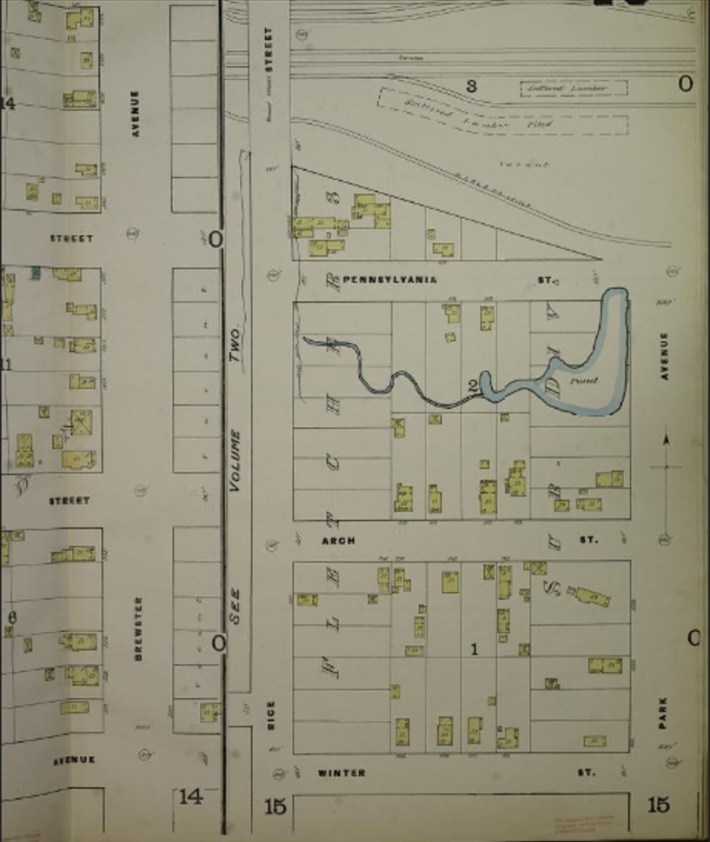

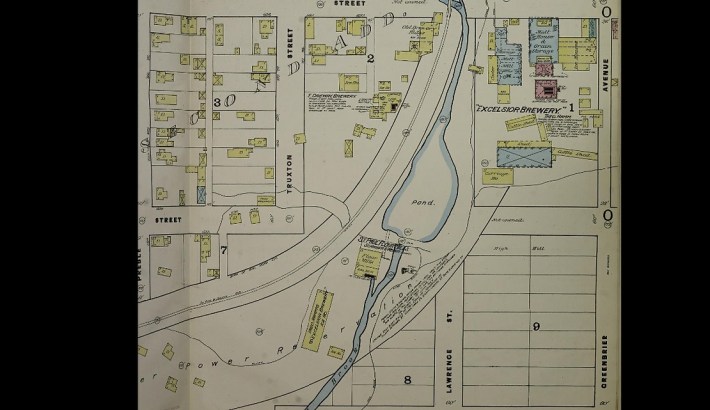

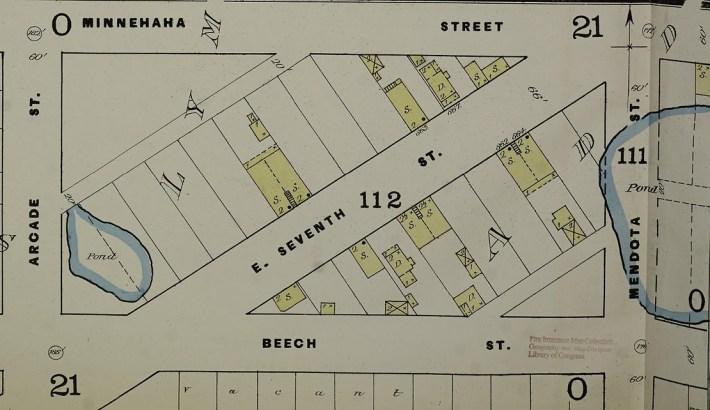

There are many more lakes and ponds that once called St. Paul home, though they were were seldom named, and there are little or no historical context to remember them by. Pictured below are several now-extinct bodies of water in St. Paul that I came across. These lakes and ponds have been posthumously named.

These lakes and ponds are just a handful of the many that have vanished during the city’s early years of industrialization. St. Paul saw an unprecedented growth in population during the latter half of the 19th century with the formation of milling, banking, and railroad industries. However, several lakes and ponds were considered truculent and subjectively impeded the progress of St. Paul’s development. The City Beautiful movement may have provided St. Paul with great parks, the Como Golf Course, and even the State Fair. However, this same movement saw the elimination of several lakes that called this region home for thousands of years.

The lost lakes of St. Paul suffered the same fate as the lost lakes of Minneapolis. The lands and bodies of water were taken by Euro-American settlers from Native Americans and brought into an expanding industrialized American empire. In the process of being integrated into the regime of industrialization, these lakes faced the unfair judgment. When these lakes stood in the way of further progress, they were leveled and filled.

This story originally appeared on The Minnesota Historian, the local history website run by Josh Biber.

Sources:

- "A Chapter of History Illustrated" St. Paul Globe. December 25, 1886.

- “Ramsey County is Banner Lake Region of the World” The St. Paul Globe, July 12, 1903. P. 20.

- Bergerson, Roger. “Cozy Lake: A Scenic Treat - For A While” Park Bugle, July 16, 2018

- “Japanese Garden Reaches St. Paul” The Saint Paul Globe, December 10, 1904. P. 12.

- “Como Woodland Outdoor Classroom Guidebook” March, 2017. www.stpaul.gov/sites/default/files/Media%20Root/Parks%20%26%20Recreation/CWOC_Guidebook.History_March2017.pdf

- “Cozy Lake, Como Park, St. Paul” Minnesota Historical Society, 1895.

- Twin City Rapid Transit. The Twin Cities Today, 1917, Minnesota. 1917. Minnesota Streetcar Museum, collection.mndigital.org/catalog/msn:473 Accessed 7 July 2022.

- “The Bridal Veil Creek Subwatershed Desk Study: A Mississippi Watershed Management Organization Watershed Assessment” The Mississippi Watershed Management Organization, May 2006. www.mwmo.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Final-BVC-Report-6.20.06.pdf

- Bennett, L. G. “Map of Ramsey and Manomin Counties : and Hennepin east” Chas. Shober & Co, 1867. https://umedia.lib.umn.edu/item/p16022coll231:3180/p16022coll231:3178?child_index=2&facet_field=date_created_ss&facet_offset=2&facets%5Bcontributing_organization_name_s%5D%5B%5D=University%20of%20Minnesota%20Libraries%2C%20John%20R.%20Borchert%20Map%20Library.&facets%5Bdate_created_ss%5D%5B%5D=1867&modal=on&query=&sidebar_page=1

- “Langford Park Bandstand: Historic Significance Evaluation” Landscape Research LLC, September 2018. www.4thinthepark.org/resources/LangfordBandStand_20180927_REV%20red.pdf

- “Langford Park, St. Paul.” Minnesota Historical Society, 1885.

- H. M. Smyth “City of Saint Paul”

- “Horse Shoe Lake, St. Paul, Minnesota” Ramsey County Historical Society, 1892. http://rchs.pastperfectonline.com/Photo/9E86324D-5FBB-4C81-9D46-472259815359

- “District 12: St. Anthony Park” Historic Saint Paul, 1983. www.historicsaintpaul.org/sites/default/files/1983%20Survey%20Dist%2012.pdf

- "Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Saint Paul, Ramsey County, Minnesota." Sanborn Map Company, Vol. 1 - 4, 1885. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn04379_001/.

- Steinhauser, Fredric. “St. Anthony Park: The History of a Small Town Within a City” Ramsey County Historical Society, Volume 7, No. 1. Spring, 1970. https://publishing.rchs.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/RCHS_Spring1970_St_Anthony.pdf

- Bergerson, Roger. “Sarita, the Lost Lake” Park Bugle, October 30, 2017.

- Bergerson, Roger. “World’s Fair in Minnesota? That’s so Yesterday” Park Bugle, April 20, 2015

- “Dean Nearly Drowns Trying to Save Boy” Minneapolis Tribune, July 26, 1912. P. 1.

- Zellie, Carole S.; Lucas, Amy M. “Merriam Park: Intensive Level Historic Resources Survey. Saint Paul, Ramsey County, Minnesota” Landscape Research LLC, 2019. www.stpaul.gov/sites/default/files/Media%20Root/Planning%20%26%20Economic%20Development/MERRIAM_PARK_FINAL_REV20191015__1212.pdf

- “A Lake to be Drained” The Saint Paul Globe, April 24, 1890. P. 5.

- Benneche, H.W.. Atlas of Minneapolis Hennepin County Minnesota. Including parts of St. Louis Park and Golden Valley Township in Hennepin County. Also Part of Ramsey County Known as the Midway District.. 1914. Hennepin County Library, James K. Hosmer Special Collections Library, collection.mndigital.org/catalog/mpls:1956

- Renner, Jon. “College Park” Google Maps, March 2019.

- Singh, Jagmohan. “College Park’ Google Maps, August 2020.

- Vezner, Tad. “Dozens of Trucks and a Mountain of Debris Leave a Maplewood Neighborhood Feeling Besieged” Pioneer Press, January 26, 2019.

- Gilbertson, Frank. “Maplewood’s Sandy Lake” Maplewoodmn.gov. https://maplewoodmn.gov/1709/Maplewoods-Sandy-Lake

- McClure, Jane. “Aurora Park,” Saint Paul Historical. https://saintpaulhistorical.com/items/show/197.

- “Drowned While Fishing: Little Conrad Kohn Meets Death at Rifle Park” The Saint Paul Globe, July 31, 1899. P. 2.