Alexander Payne makes movies about unlikeable, obsolete men, and then leaves us to wonder whether they’re obsolete because they’re unlikable or unlikable because they’re obsolete. The people around them, especially the women, just seem so much more functional, adept at adjusting to times that aren’t a-changin’ nearly as swiftly as the cranky protagonists contend. Payne’s films can feel like special pleading, especially if you’ve ever had to tussle with the learned helplessness of such a male, or if you suspect that, despite your best efforts, you’ve devolved into one yourself.

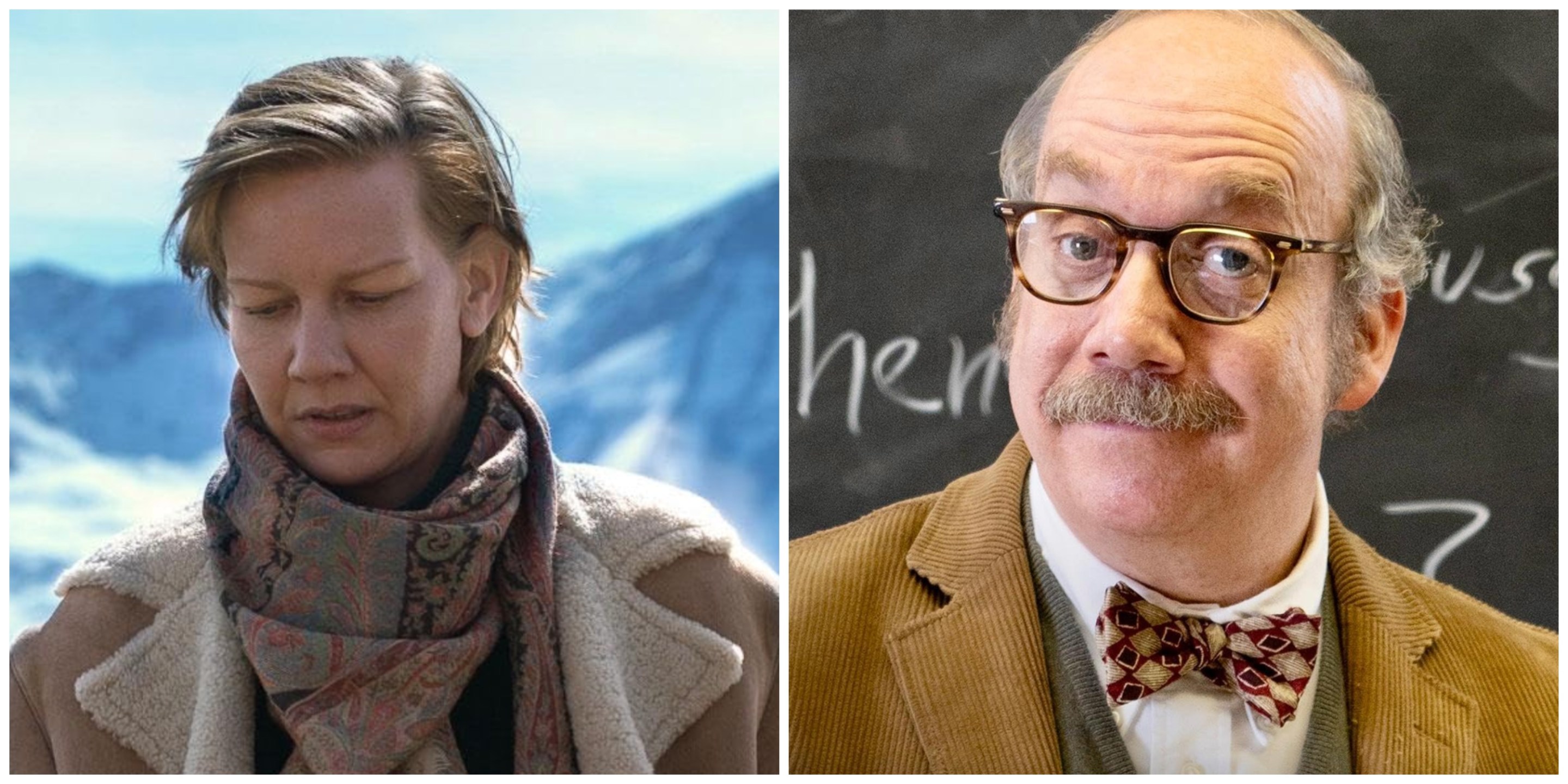

In The Holdovers we meet the latest addition to Payne’s roster of curmudgeons, Paul Hunham, a staple in many high schools and probably every single prep school: the sexless (if not virginal) odd-smelling disciplinarian. It’s 1970 and Hunham, played by Paul Giamatti, is a teacher of ancient history at the Barton Academy and a graduate of that fictional Massachusetts school as well. The kids call him “Walleye” (at last, representation for us lazy-eyed humans), as do some of his colleagues, too, and he’s such a hard ass the headmaster (a former student) holds a grudge against him.

As a result, Hunham is condemned to spending Christmas break with five students who have no home to go to for the season. (It’s not much of a sacrifice—Hunham seems to have nowhere to go anyhow.) There are two young kids (one Mormon, one Korean) and three older students: an absolute asshole named Teddy, a football player in a battle of wills with his dad, and bright-yet-underachieving Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa), who brandishes a truly formidable Adam’s apple.

At this point, we’re primed for some sort of Breakfast Clubby interaction between Hunham and the five mismatched holdovers, where everyone learns a little lesson about each other, but Payne swerves away from that simple resolution. Instead the film centers on the relationship between Paul and Angus, which evolves from purely adversarial to a wary kind of trust and respect. Intervening between them is school cook Mary Lamb (Da'Vine Joy Randolph), whose son, a former student at Barton, died in Vietnam; Paul and Mary bond over The Newlywed Game and Canadian Club and their resentment of the prep students' brattiness.

In typical Payne fashion, characters fumble into romantic cul-de-sacs, secret pasts are revealed, and misanthropes are slowly humanized. Reasons emerge for characters to go off campus, and, like leaving the boat in Apocalypse Now, there are consequences each time, some more comic than others. The Holdovers rambles a bit, but that’s a positive—it doesn’t lead us exactly where we expect it to, even if it doesn’t take us anywhere particularly unfamiliar.

In recent years, of course, Payne has been in danger of becoming obsolete himself. After the success of Sideways in 2004 he began work on a passion project, Downsizing, surfacing periodically for decent-to-good films in the interim before the messy results of his long obsession were released in 2017. The Holdovers returns him to the politics of the classroom broached in Election, reunites him with Sideways’s Giamatti, and comes as close to a crowd pleaser as Payne dares. It’s “a satisfying return to form,” if you’d like a quote for the trailer, and Payne’s Wikipedia page even has a hopeful and perhaps premature section tagged “2023–present: Resurgence.”

But phoniness creeps in around the edges of The Holdovers. Though the movie was shot digitally, Payne indulges in a grubby nostalgia, with effects designed to simulate the grain of ’70s film. It’s as though he doesn’t just want his film to recall the era when it was set, but also to return us to an age “when movies were movies.” Some of these choices are effective—cinematographer Eigil Bryld achieves a masterfully bleak Christmastime look. Yet in making a film about the kind of film that existed 50 years ago, Payne draws unflattering comparisons to his cinematic betters, and makes us question his motives.

Why 1970, after all? True, a whiff of antiauthoritarianism is in the air—or maybe that’s just some contraband ditchweed. The rebellious atmosphere at Barton is mild, marked by a little pot, a little porn, some hair below the shirt collar. (One way prep schools contain revolt is by giving kids arbitrary rules to break, so you can feel like a rebel just by loosening your tie.) Vietnam does linger in the background—as a place where the underprivileged are killed or maimed, and in the threat from Angus’s parents to send him to military school—but it feels like more of a dramatic device than a real presence in the characters’ lives.

Still, the slightly old-fashioned moral drama Payne sets up here could only play out in a time (we’re meant to believe) when you knew which rules it was appropriate to break and when. Payne requires an entrenched institutional authority so he can tell a story about how important it is to honor the humane spirit of the law rather than slavishly follow its draconian letter. That’s a pretty fuckin’ weird thing to do when you think about it.

Especially as its third-act revelations roll in, the humanization of the characters can feel a bit mechanical if you’re not in the mood. I usually feel like I’m being worked over in Payne’s movies, and often I push back. But here the cast coaxed me along for the ride. As Hunham, Giamatti plays a man who has calcified into a caricature. The affectations he may have once thought were flippantly acerbic are now tics, and his code of honor, which he wields with a not-unreasonable sense of class resentment, is brittle as well, a defense he developed for long-past battles. Sessa is the perfect foil, not a rebel in any sense, just a kid stifled by his parents and his surroundings. And though Mary’s arc is a bit too delineated—we know exactly what she has to process and it’s just a question of figuring out how—Randolph’s performance does feel true to life.

In the end, The Holdovers comes down to lessons learned and sacrifices made, and Hunham is given a dramatic opportunity to exercise his nobility. There’s a constant tug between the actors striving to inhabit their characters and explore their complexities and Payne limiting them to the roles he needs them to play. But honestly, if this was as hokey as movies ever got, especially as Oscar season rolled around, this would be a fine world indeed.

***

There’s not much point in complaining about a movie’s marketing, especially at a time when getting anyone in a theater is a challenge, but the website for Anatomy of Fall really does a disservice to Justine Triet’s carefully balanced courtroom drama. Not only is the domain didshedoit.com, but upon loading the page you’re immediately given two big YES or NO block options to click to enter the site, which reduces a prolonged, fraught examination on the slippery nature of truth and evidence into a parlor game. Aren’t we allowed even a little tiny bit of ambiguity anymore?

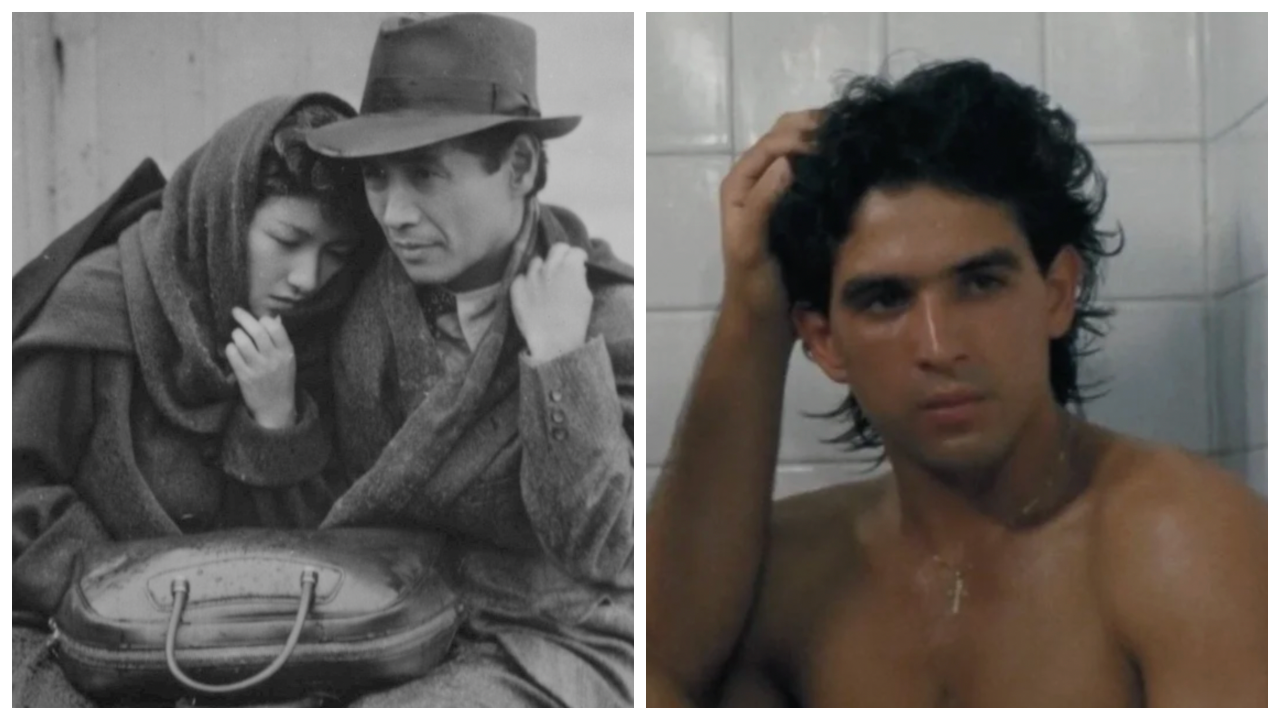

The film’s setup is simple, with just enough elements in play to make what happened uncertain to the viewer. Sandra (Sandra Hüller), an established novelist, and her husband, Samuel (Samuel Theis), a teacher and significantly less successful writer, live in Grenoble, his hometown in France, with their partially blind son Daniel (Milo Machado Graner). On the day of Samuel’s death, a student named Zoé (Camille Rutherford) comes to their home to interview Sandra, and their discussion turns to the prickly question of how a writer’s life is reflected in her work.

Midway through their talk, Samuel, who is remodeling the attic, starts blasting an instrumental version of 50 Cent’s “P.I.M.P.” so loudly the two women can’t continue. Zoé drives away, and at around the same time, Daniel and his seeing-eye dog Snoop leave for a walk, and the camera leaves with them. When Daniel comes home, he finds his father dead on the ground outside their home, the attic window above open.

This brief series of events provides the grist for the film that follows. As she’s transformed in the eyes of the law from grieving widow to prime suspect, Sandra responds with unsettling reserve, and her lawyer, Vincent (Swann Arlaud), has to convince her of the danger she’s in. We’re left to wonder whether she’s as icy as she seems or if she’s stunned by how swiftly the apparatus of justice zeroes in on her.

Investigators overrun her home, requiring her to re-enact conversations with her late husband and to watch a dummy representing his body drop repeatedly from the window. A guardian (Jehnny Beth of the band Savages) is appointed by the court to oversee Daniel, who becomes a key witness.

Once we’re in the courtroom, with facts exculpatory and damning slowly trickling out, the plot of Anatomy of a Fall becomes a kind of austere pulp, its subject matter juicy but its mood somewhat rigorous. Anchoring that tone is Hüller, who first achieved widespread attention as the straight-laced daughter of a madcap father in Toni Erdmann and has been celebrated this year for her role as the wife of a Nazi commandant in Jonathan Glazer’s well-reviewed The Zone of Interest. She’s so composed that we’re not waiting for her to crack, as we might with a more conventional performance. But crack she does, and with something more than a typical dramatic burst, because Hüller shows a woman not just defending herself but defending her fundamental belief in the complexity of human motive, a belief she’s loath to surrender for the sake of proving her innocence.

But reluctantly, Sandra learns that she has to set aside her novelist’s beliefs in the unknowability of the human heart and to offer an opposing believable narrative to the prosecution's. Samuel was suicidal, she implies, and he jumped to his death. But as we learn more details about the relationship between Sandra and Samuel, her faith in complexity is affirmed. A couple creates a sort of third entity between two people that can never be wholly understood from the outside. We have countless motives for concealing or altering the truth, and any conversation with a partner can make you sound like a potential murderer.

For an American, there’s always something particularly compelling about a European courtroom drama—the dramatic elements are similar but the ground rules are different. While watching Anatomy of a Fall. I couldn’t help but think of Alice Diop’s Saint Omer, another recent French courtroom drama about a woman on trial with a stunning central performance. A very different movie, a very different woman, a very different performance, but in both cases what we watch feels less like a woman on trial and more like a trial happening to a woman.

Because we’re so close to Sandra the entire time, we instinctively root for her, even though she’s far from an ingratiating character. No guilty person could possibly be so reluctant to play the games of justice, could she? And Antoine Reinartz is unnerving as the prosecutor with a shaved head and a condescendingly stooped gait, swooping in with vicious questions and then retreating smugly to his post. She’s painted as a woman who has insisted on having time for her work (i.e., a bad mother) and who had affairs at that. And language complicates the story as well: Sandra is German but is forced to speak French in the courtroom most of the time.

All Triet has to do for Anatomy of a Fall to work is not show what happened. Yet even after a verdict is reached, the air isn’t entirely cleared. The more evidence that we’re given, the less certain we are of everything. Far from an invitation to speculate, however, that seems to be the point: actual truth and legal truth are not identical. How or if you choose the website’s cheap question—”did she do it?”—says more about you than it does about the film.

GRADES

The Holdovers — B+

Anatomy of a Fall — A-