“The lake was a perfect inland sea, surrounded by the most beautiful timber and wherever we landed the soil was of the richest character.”

Territorial Gov. Alexander Ramsey’s personal diary, May 27, 1852.

One year earlier, Gov. Ramsey had leveraged one of the shadiest deals in U.S. history, having purchased nearly 2 million acres of Minnesota land and water from the Dakota people. For all that land, the territorial government paid the Native Americans about three cents per acre.

Nestled within that acreage was a sprawling lake with forested shores. The lake had been seldom visited by Euro-Americans, it being several miles to the west of Fort Snelling with only a few narrow trails through the woods to access it. This lake was first given the name Peninsula Lake for its many peninsulas and points after Calvin Tuttle and Simon Stevens visited in 1851. One year later, Tuttle, Stevens, Gov. Ramsey, George Meeker, and Shelton Hollister journeyed there together. During this visit, a new name was chosen for the large body of water: Lake Minnetonka. (To be clear, the name Minnetonka was not new; it had been used for generations among the Dakota people.)

When, exactly, Lake Minnetonka was discovered by Europeans and Euro-American settlers is largely debated. Was the lake discovered by two adventurous boys from Fort Snelling in the 1820s? Or had it been visited decades earlier by the English explorer Jonathan Carver?

Carver’s potential trip to Lake Minnetonka is debated, as he never explicitly mentioned visiting there in his books or notes of his travels. Yet, there is scant circumstantial evidence that Carver was the first European to see the lake during the winter of 1766 alongside a company of the Mdewakanton Dakota.

Carver was dispatched by the British government to find a Northwest Passage through the interior of North America in 1766. A secondary task was asked of Carver: To learn more about the Native Americans in the vast northwest during his travels. Carver mostly traversed and mapped the northern regions of the Mississippi River. However, he did travel up the St. Peter’s River (now the Minnesota River) to winter with the Mdewakanton Dakota.

Carver’s explorations brought him to a tributary he anointed as Carver’s River. Examining his maps, this self-named tributary was likely what we now know of as Minnehaha Creek. Those same maps depict a vast lake that can be assumed to be Lake Minnetonka, roughly 20 miles upstream from the rivulet’s delta with the Mississippi.

Carver’s travels that winter stopped about 25 miles up the Minnesota River, where the city of Carver, Minnesota, is presently located. At this point, he was only about 10 miles south of Lake Minnetonka. It can be presumed that, during his time visiting with the Native Americans of the region, that he very likely was brought to Lake Minnetonka or, at the very least, informed of a massive lake not far from where he had set up camp. After his excursion, Carver returned to England in 1769, where he later published a successful book about his extensive travels in the new world.

Despite Carver’s potential visit to the lake in the mid-1700s, the lake’s marriage with Euro-American settlers began with the construction of Fort Snelling in 1812. A decade after the fort was built, Lake Minnetonka was undoubtedly visited again by two Euro-American boys.

In 1822, Fort Snelling residents William Joseph Snelling and Joseph Brown decided to paddle up what was then Carver’s River near Fort Snelling to see where its headwaters were. Snelling and Brown canoed up the creek with a team composed of others from Fort Snelling as well as a team of Mdewakanton men who told stories of a large lake that lay ahead. Somewhere during this journey, Snelling allegedly turned back to the fort after mosquitos proved too much of a nuisance. Brown and the group of Mdewakanton men decided to proceed up the creek. After two days of travel, Brown’s canoe emerged from the creek into a large bay of a giant lake that revealed itself to the group. Brown and his crew camped on the shore that night, returning to Fort Snelling the next day to claim discovery of the headwaters of the creek.

Thus, the name Carver’s River faded and a new name for the creek was adopted: Brown’s Creek. It wasn’t until the 1850s that the name Minnehaha Creek replaced the former after Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s popular poem, "The Song of Hiawatha."

Euro-American settlers were prohibited from settling Minnesota west of the Mississippi River until the 1851 Traverse Des Sioux Treaty, which legalized it. Thereafter, entrepreneurial millwrights, farmers, and colonists from the east flocked upon the shores of Minnehaha Creek and, shortly thereafter, Lake Minnetonka; they brought new technologies such as turbines, dams, waterwheels, and mill ponds to harness the energy of the water flow into a milling industry that surged Minneapolis into national relevance. To be clear, this history is not to discount the Mdewakanton Dakota community that once used the creek and Lake Minnetonka for food, hunting, farming, travel, and trade before Euro-Americans arrived. The Mdewakanton were equipped with an array of technologies such as hunting equipment, canoes, and several farming techniques.

As settlement began around Lake Minnetonka in the 1850s, early homesteaders had a penchant for naming pieces of Minnetonka’s wilderness after themselves. The first to do so was George Meeker, who was with Alexander Ramsey during their exploration on May 27, 1852. Meeker chose to name the island they were on after himself as Meeker’s Island—now Big Island. It’s important to note that history tends to lend credit to the names around Lake Minnetonka after the men of families who homesteaded its shores. I’m certain that several landmarks and places around Lake Minnetonka should have been credited to the women of the region, as their homesteading efforts were just as important.

In other instances, hometown names from New England and Europe—such as Orono, Excelsior, Navarre, Casco, and St. Albans—made their way to the shores of Lake Minnetonka in sentimental admiration. In some localities, places were named after poems and poets from the 1700s and 1800s. Lastly, concocted anglicized Native American names such as Minnetonka, Wayzata, Minnetrista, Mahpiyata, and Wawatasso remain as a last rites for the dispossessed. One thing is for certain: Many of the names of places around the lake were disputed by early settlers and have since changed several times over. For example, the previously mentioned Meeker’s Island became Morse’s Island before the name was colloquially, then formally changed to Big Island in the 1890s.

Many of the first settlers who purchased land around Lake Minnetonka were able to do so with nothing more than a dream and some spare change, plus plenty of time, toil, trouble, expense, anxiety, and timber. The below history of how the bays, points, and islands throughout Lake Minnetonka were named only begins to scratch the surface; to keep this as concise as possible, some events and eras have been abbreviated.

Moving Clockwise from Gray's Bay

Imagine you were circling Lake Minnetonka clockwise by boat starting from Wayzata, as countless people did in the late 1800s. The first stop on this tour would be Gray’s Bay, the northeastern-most bay and outflow, named in 1853 after Amos Gray and Betsey Streeter Chowen, original settlers in the area. Up until the 1890s, some also referred to Gray's Bay as Outlet Lake, for this bay empties Lake Minnetonka into Minnehaha Creek.

To the west of Gray’s Bay is Wayzata Bay, which was first known as Lake Bryant, after the famed poet William Cullen Bryant. This bay was later given the name Wayzata, which is the anglicized Dakota meaning for north shore or northern god.

Wayzata Bay has many points and prominences. The eastern shore was once known as Bourgeois Mound, after John Bourgeois, who came to Wayzata in 1853. It was at this location that Bourgeois, with the help of John McGalpin, built a small squatters shanty. The two later moved to Minnetonka Mills where they were employed as blacksmiths and coopers. Bourgeois Mound was later known as Carpenter’s Point, after H. M. Carpenter who owned the land. The road that intersects this point, Bushaway Road, is the no-nonsense anglicized pronunciation of Bourgeois.

Protruding from the southern shore of Wayzata Bay is a prominent point that was first known as Stetson’s Point after Euro-American landowner V. C. Stetson. The name gradually changed to Cedar Point. This famous point gets its name after the spattering of red cedar trees that grow there in abundance. There is, confusingly, a second Cedar Point on Lake Minnetonka, but more on that later.

About a third of a mile west of Cedar Point is Breezy Point. This fabled peninsula was first described by Elizabeth Fries Ellet in 1852 as, “an extremely narrow headland half a mile in length, running out from the southern shore." Ellet first called this peninsula Point Wakon, wakon being an anglicized Dakota term for something of spiritual or supernatural importance. The name was appropriate, as the peninsula was a cherished gathering place for the Mdewakanton Dakota.

The point had two famous landmarks. The first was a large, oval boulder that was painted with red and yellow spots. This boulder was used for spiritual practices by the Dakota peoples. The wakon boulder is long gone; rumors and stories suggest that an unnamed wealthy St. Louis summer tourist absconded with the rock to use it as a conversation piece inside their parlor back home during the 1870s. Sadly, the pilfering of Native American artifacts was common practice at Lake Minnetonka during the late 1800s. To make a quick buck, landowners would often invite tourists to their property to exhume Native American burial mounds and take their contents as some sort of sick souvenir.

The second famed landmark on Breezy Point was Spirit Knob, a prominent, 30-foot knoll at the tip of the point. The side of the knoll facing Wayzata bay was wooded, whereas the side facing Brown’s Bay and the lower lake was an exposed clay bank. In 1879, Spirit Knob was purchased by the Breezy Point Club and subsequently leveled.

Just across the bay from Breezy Point is Lookout Point, which was first known as Harrington Point after John Harrington built his house there in 1854. Harrington later built a 16-bedroom addition onto his home known as the Harrington Inn. Harrington’s Lakeside Home and Harrington Inn burned down in 1899. Over the next several decades, the Harrington Point name slowly faded as Lookout Point took its stead.

Just beside Lookout Point to the northeast is the less prominent Wicks Point, sometimes known as Pryor Point. This little prominence was a marshy peninsula in the 1860s. The land was later filled by the Pillsbury family, hence the name of the road, Pillsbury Drive, that extends to the point.

Leaving Wayzata Bay, the lake opens up to a section known as the lower lake. Lower lake is confusingly to the north and east of upper lake, hence lower lake appears as being the upper portion of Lake Minnetonka. However, upper and lower Lake Minnetonka were named for the flow of the water through the lake. Lake Minnetonka is mostly fed by Six Mile Creek in upper lake’s Halsted Bay, whereas the outflow of the lake is in lower lake’s Gray’s Bay, which flows into Minnehaha Creek.

Continuing clockwise on the journey around the lake, we arrive at Robinson Bay, which gets its name after Alfred B. Robinson, an original Justice of Peace in Wayzata. Robinson came to Minnesota in 1842, and worked at Fort Snelling until 1845. Robinson relocated to the shores of Robinson Bay in 1853, where he later married and started a family.

Just inland from Robinson Bay is a small lake that is not connected to Lake Minnetonka known as Lake Marion. That lake was named after Marion Gale, the third daughter of Samuel C. Gale. The Gale family was important in both Minneapolis and at Lake Minnetonka during the late 1800s. Of their many business ventures, the Gale family was known for operating the Maplewood Inn, which was situated near the present intersection of Maplewood Road and Gale Road in Woodland.

Wrapping around the south shore of Robinson Bay is Gibson Point, anointed so after Charles Gibson and family, who acquired this portion of land in 1870 to build their large estate, Northome. Gibson was an esteemed lawyer from St. Louis, and amassed considerable wealth after offering his legal services to the Prussian and Austrian royal families. With it, Gibson commissioned the construction of Hotel St. Louis, which overlooked Minnesota's St. Louis Bay. The hotel was famed for hosting the Northwestern Lawn Tennis Championships as well as cementing itself as one of the first resort-style hotels on Lake Minnetonka. The Gibson’s Northome residence was destroyed by a fire in the 1890s, but the stone arch that marked the entrance to their property can still be driven through on the aptly named Northome Road.

Charles Gibson also funded the creation of Light House Island. The name is a misnomer, as there was never a lighthouse. The island is man-made, created by filling dredged gravel and sand from the nearby St. Louis Bay. This same technique was used to create Bug Island, a smaller island to the southeast that serves as a mooring for sailboats. Gibson, along with several other prominent citizens around the lake, founded the Minnetonka Yacht Club here in the summer of 1882.

Extending to the south from St. Louis Bay is Carson’s Bay, which was initially known as Pig’s Inlet until the 1870s. Tucked between Deephaven, Greenwood, and Cottagewood, this bay later adopted the last name of Elijah Carson, a distinguished early member of the Excelsior community.

The most prominent spot in Carson’s Bay is Chimo Point, which intersects the bay from the southeast. In 1890, Hazen J. Burton built his family a (still-standing!) Queen Anne-style home that he called Chimo, an anglicized Dakota word meaning welcome.

Around the Chimo residence was Burton’s personally constructed nine-hole golf course, which he called the Cow Bowl. Finished in the 1890s, the Cow Bowl was one of the first golf courses in Minnesota.

Leaving Carson’s Bay, boats have to pass through the narrow gap between Bug Island and Grandview Point, which is aptly named for the point’s sweeping views of Carson’s Bay to the south, St. Louis Bay and Light House Island to the north, and the lower lake to the west.

About a half-mile to the west of Grandview Point is Swift Point, adopting the last name of Lucian and Minnie Swift, who were owners of the old Minneapolis Journal newspaper. The Swifts purchased the property to build their home, Katahdin, on the point. Hence, the point is still interchangeably known as Swift Point and Katahdin Point.

Wrapping further around the lower lake, about two miles north by road from Excelsior is Ferguson Point, name after William and Lydia Ferguson.

William , along with his wife Lydia and their two children, came from Elmira, New York, after reading about the homesteading opportunities at Lake Minnetonka. On May 2, 1854, the Ferguson family traveled the Erie Canal to Buffalo, then hopped aboard the Southern Michigan steamboat, which took them to Monroe, Michigan. Next they made their way to Chicago by way of rail, and, after a few days, took a train to Galena, Illinois. Once in Galena, the family took a Mississippi steamer named the War Eagle, finally arriving in St. Paul on May 22, 1854.

As the Ferguson family journey shows, travel during the 1800s wasn’t measured in hours or days, but in weeks and months. The anxiety, uncertainty, excitement, and distress that they experienced while coming to Minnesota was undoubtedly shared by all of the early settlers of the Lake Minnetonka region. Lydia Ferguson recollected in her personal memoirs that she felt the move to Minnesota was a mistake. Her family left their creature comforts in New York to make way for an unknown entity that lay ahead in Minnesota. She was devastated to leave her prized possession, a piano gifted to her by her mother, behind in New York. Her husband informed her that there was no place for a piano in the wilderness that was their future.

Once arriving at St. Paul, Lydia and the children stayed at a boarding house while William hitched a carriage west to Lake Minnetonka. Arriving in Excelsior after two days of travel, William found that the majority of prime real estate along the lower lake was already spoken. Then he met with William E. Smith of Minnetonka Mills. Smith advised Ferguson that he had a home for sale in what would become the Cottagewood area. Ferguson found the land to be suitable, and purchased the property for $225. Smith relocated to Smithtown Bay (named after him and his brothers), while the Fergusons moved to their new home on June 15, 1854.

William was known to love the frontier lifestyle. His wife Lydia, however, often wrote about her longing to return to their old life on the east coast where her family was.

Things never got easier for the Fergusons. The winters were terribly cold; their small cottage lacked suitable insulation and protection from the elements. Their livestock and chickens were often taken in the night by coyotes and wolves. Lydia and her children were also weary of the Mdewakanton people that often visited them while passing through the region. The Fergusons were extremely isolated, as their nearest neighbors were two miles south in Excelsior, which was only accessible by boat. Lydia rarely made the trek, as she didn’t know how to swim.

Then devastation struck the family. While returning from a church service in Excelsior on November 22, 1857, William Ferguson’s boat capsized about a mile south of his home at Bickford Point (next to the Old Log Theatre, named after the landowner E. Bickford). The boat sank with William aboard. William’s body was recovered and buried at Crystal Lake Cemetery in Minneapolis. Excelsior resident Charles Galpin witnessed the capsize from shore; he bore the task of informing Lydia of her husband’s death.

Lydia later remarried for a few years before divorcing her second husband. Her children stayed by her side, later building and managing a small hotel on their property. Lydia passed away at Ferguson Point in 1895, still longing for her old life and her prized piano back east.

Traveling further south and wrapping around Solberg’s Point (named after O. N. Solberg) we enter the southeasternmost bay of Lake Minnetonka, St. Albans Bay. The bay is named after the failed village of St. Albans which was once situated on the eastern shore of the bay. The town failed by 1859, but the bay kept the name of the town.

To the west of St. Albans Bay lies Excelsior Bay, named after the town that encapsulates the bay’s southern shore. West of Excelsior lay Gideon’s Bay, named after Peter M. Gideon. Gideon held the position of superintendent at the State Fruit Farm, which was a 160 acre plot that he owned upland from the western shore of this bay in 1853. Gideon is famed for creating the Wealthy Apple, named after his wife, Wealthy Hall. In 1912, a plaque was unveiled outside of the Gideon homestead that commemorates his horticultural endeavors. The plaque can be visited today at the intersection of Gideon Lane and Glen Road in Tonka Bay.

To the northeast of Gideon’s Bay in the center of the lower lake is Gale Island. Gale Island has gone through a few name changes since the 1800s. First known as Gooseberry Island, the small dot of land initially served as a makeshift stockade during the U.S. Dakota War of 1862. Several early settlers of Excelsior feared a potential conflict with the Native Americans in the region. Thus, a few of the townsfolk descended upon the island to build a rudimentary fort in the case of an attack.

The fort was never used, and after the war ended the island was purchased by the family of Harlow Gale. The Gales built their octagonal summer cabin, Brightwood, on its shores. Thus, for a number of years, the island was known as Gooseberry Island, Brightwood Island, or Gale Island depending on who you were speaking to. Brightwood remains on the island, but the Gale family no longer owns the land. However, the last name stuck—hence the name of the island today.

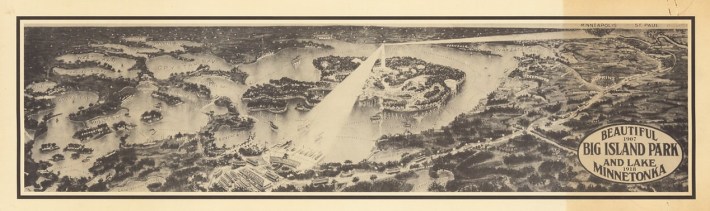

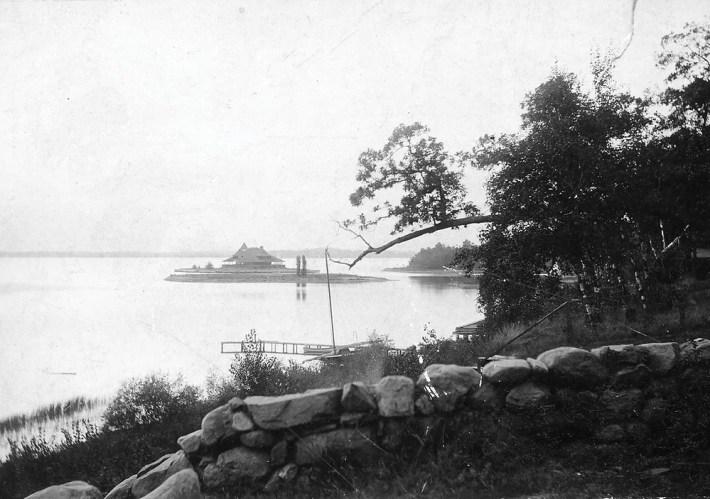

Just north of Gale Island is the most famous landmark at Lake Minnetonka, Big Island. Big Island, like many places throughout the lake region, has gone through many different titles since its Euro-American discovery. The island was first known as Meeker Island after Bradley B. Meeker, who claimed it as his in 1852. After a few years, Meeker sold the island to W. and J. Morse in 1856 for pennies on the dollar. During the latter half of the 1800s, the Morses sold parcels of the property for summer cottages.

Olaf Searle purchased the western half of Big Island from the Morse family. Searle is chiefly responsible for dredging a channel through the middle in the 1890s to separate his plot of land on the western half from the rest of the cottages on the east half, essentially creating a physical barrier that cut the island in two.

By 1906, the Twin Cities Rapid Transit Company purchased a large portion of the eastern half of Big Island to be used as an amusement park at the end of their streetcar line which terminated in Excelsior. Big Island Amusement Park was short-lived, shuttering in 1911.

About 200 yards from the northwest corner of Big Island is Huntington Point, a long extension of the mainland that makes up a majority of the city of Minnetonka Beach. The point was first known as Holmes Point after the first owner, John H. Holmes. It was colloquially changed to Huntington Point in 1874 after the land was purchased by Josiah Huntington.

To the west of Huntington Bay is the well known Lafayette Bay, formerly known as Holmes Bay. This bay received its name after the James J. Hill’s Lafayette Resort that straddled the north shore of the bay in 1882. Hill’s Lafayette Resort was short-lived, burning down in 1897. The land was later repurposed into a nine-hole golf course where the Lafayette Club is currently located.

Lafayette Bay also contains the channel connecting the upper lake to the lower lake, known as Hull’s Narrows. Commonly referred to as The Narrows, this channel was originally a tiny creek that connected upper lake to lower lake known as Crystal Creek. In 1853, Rev. Stephen Hull built a farm overlooking Crystal Creek. With Hull’s permission, the creek was dredged and widened in 1873 for steamboat navigation between the two sections of the lake. The first steamship to pass through Hull’s Narrows was Charles Galpin’s side-wheeler, the Governor Ramsey.

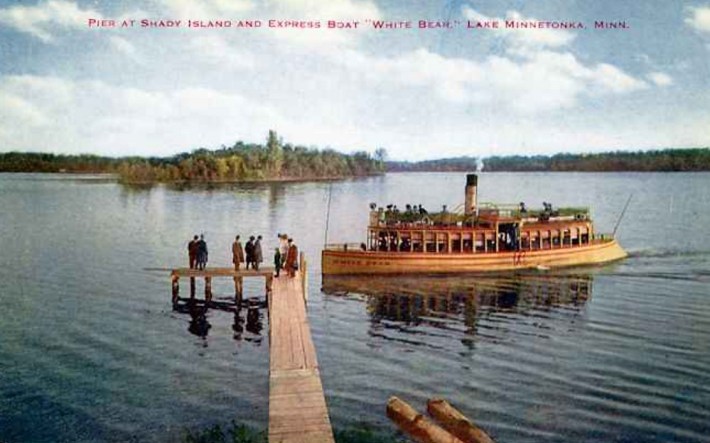

To the west of The Narrows, the upper lake opens up to even more bays, islands, points, and peninsulas that comprise the upper lake. Whereas the majority of the lower lake was settled and named throughout the 1850s, the upper lake was further from population centers, thus it was mostly settled a few decades later throughout the 1860s and 1870s. The first of the upper lake bays is Carman Bay, named after John Carman who claimed 14,000 acres of land and water in the upper lake region in 1853. Carman’s first home was a two-room log cabin built in the fall of 1853 on Shady Island, which Carman named after the abundance of foliage. After a year on Shady Island, John Carman and his family sold their small cabin to the Westlake family and moved to Spring Park Peninsula, which was later named Casco Point after a small town in Maine.

Continuing on our journey, to the south of Carman’s Bay is Locke Point, which gets its name after David Locke, who came to Lake Minnetonka from Indiana in 1855. Locke didn’t stay in Minnetonka long, heading back home about a year later. But in 1865, Locke returned, moving to Hastings and, eventually, back to Lake Minnetonka. Locke and his family resided along the lakeshore until he passed away in 1877.

About a mile-and-a-half to the west of Locke Point is Howard’s Point, named after Silas Howard who was born in Rhode Island in 1804 to a family of modest wealth. Howard ran a coal and wood trading business in Rhode Island until he came to Minnesota in 1858 at the age of 54 with his wife Lydia and son Simeon. Today, Howard’s Point Marina and Howard’s Point Road recall the Euro-American settler.

Beyond Howard’s Point are a collection of several islands. The first of these is Spray Island, which was first known as Hog’s Island until the name colloquially changed in the 1880s to the current name.

Just north of Spray Island is the smaller Goose Island or Wild Goose Island as it is sometimes referred to. Goose Island was originally owned by railroad magnate James J. Hill’s holding companies until G. E. Reel from Christmas Lake purchased the island from Hill for $162 in the 1860s. Reel built a small cabin on the island but seldom visited. The island is now owned by Three Rivers Park District.

Goose Island is within Spring Park Bay, formerly known as Byer’s Bay after an early landowner in the area. The bay later adopted the name of the city, Spring Park, which surrounds the shoreline of the bay. In turn, Spring Park gets its name from a naturally occurring spring located on Casco Point.

To the southwest of Goose Island is Shady Island and the larger Enchanted Island. The exact reason for the name is debated, but many historians agree that it was likely given as a result of Enchanted Island once being a frequent gathering place for the Mdewakanton Dakota people. It’s said that there was a natural amphitheater where countless Native American artifacts were discovered (and have long since been taken). In the late 1800s through early 1900s, Enchanted Island was sometimes referred to as McCormick’s Island after Samuel McCormick, who owned the eastern half of the island.

To the north of Enchanted Island lay the larger Phelps Island. Phelps Island was first known as Noble’s Island after its first Euro-American landowner, O. J. Noble, before the island was sold to Edmund Joseph Phelps in 1875. Technically, the island was initially a large peninsula. In the 1880s, channels dredged at Cooks Bay and Spring Park Bay turned the peninsula into a de facto island. Phelps Bay to the south of Phelps Island is also named after E. J. Phelps, who was a successful banker in Minneapolis.

To the south of Enchanted Island and Phelps Island is a collection of three islands, starting with Wawatasso Island. Once known as Dunlap Island, Wawatasso Island has had several spelling iterations throughout the years. The island was named after the legend of Wawatasso, a young, handsome Ojibwe man who saved a Dakota girl from drowning at the lake. The girl’s father, thinking that Wawatasso was hurting his daughter, shot Wawatasso and left him to perish.

Not far to the southwest from Wawatasso Island is Eagle Island, named after a community of bald eagles that once nested on this island. Just to the west of Eagle Island is Crane Island. Crane Island was once a heronry, a nesting place for blue herons that would come to the island in droves during the spring and summer months. It was customary in the late 1800s for steamboats to sound their whistle when passing Crane Island to unsettle the birds and make them take flight en masse, which was quite the attraction at the time. In 1906, a tornado came through this portion of the lake. The tornado’s devastating winds uprooted most of the trees on Crane Island; thus, the herons mostly moved over to Wawatasso and Eagle Island where the tornado did less damage.

After the tornado felled the trees on Crane Island, Rev. C. Emerson Woodward from the Minneapolis Bethlehem Presbyterian Church purchased the land to form the Crane Island Association. Summer cottages were erected where the trees once stood. Today, the cottages make up the Crane Island Historic District, a community of highly coveted private summer dwellings.

Wawatasso, Eagle, and Crane Islands are at the mouth of Smithtown Bay. Smithtown was named after brothers Elliot and William Smith, who owned a tract of land on the bay. The brothers had ideas to start a town called Smithtown in the 1850s; here they built a mill, two log houses, and widened a Native American trail to accommodate carriages from Excelsior, which they coined as Smithtown Road. Despite the Smith brothers’ efforts, the town never materialized and settlers opted for Excelsior instead.

Beyond the trio of islands to the north is Cook’s Bay, just past West Cedar Point (the second Cedar Point on the lake) and Hardscrabble Point. This bay adopted the namesake of Mathias Cook (John Carman’s son-in-law), who built one of the first year-round residences in the upper lake region during the summer of 1854. Cook’s home was a log cabin, 13 feet by 20 feet with a small attic level for storage. In 1868, Cook built and operated the three-story Lake View Hotel which overlooked Cook’s Bay at what is now Surfside Park.

To the west of Cook’s Bay is Priest’s Bay, named after J. D. Priest, who owned a farm on the north shore of this bay. Priest’s Bay has a channel that was dredged and widened in 1880 to accommodate boat traffic into Lake Minnetonka’s westernmost Halsted’s Bay.

Halsted’s Bay borrows the last name of Frank W. Halsted, who was the first Euro-American settler near this bay in 1855, long before any other settlers came to this region of the lake. Halsted built his small house here known as The Hermitage. Frank W. Halsted died on Lake Minnetonka in 1876. After Frank’s death, his brother, George B. Halsted, assumed ownership of The Hermitage until the home burnt down, claiming George’s life in 1901.

Exiting Halsted’s Bay by boat, one can take the back channels of upper lake’s Emerald Lake (named after its green shoreline of reeds and lilies), Seton Lake (named after the Seton Guild, an all-girls Catholic school that abutted the shore), and Black Lake (named after the dark, shaded waters) to access Harrison Bay in the West Arm of Lake Minnetonka.

Nathaniel H. Harrison homesteaded the shores of Harrison Bay in 1855, where he lived for 11 years. Harrison was a shipbuilder and carpenter originally from Virginia. He helped to build many of the famous sailboats and steamers of Lake Minnetonka’s heyday, including the May Queen and the Halsted brothers steamboat, the Mary.

To the north of Harrison Bay beyond Three Points Peninsula is Jennings Bay, adorning the last name of Frederick A. Jennings. Jennings was born in England in 1807. In his thirties, he moved to New York where he worked in the printing industry. Similar to the Fergusons who found out about Lake Minnetonka in New York Newspaper ads, so too did Jennings. In 1855, Jennings purchased a homestead property on the west side of the bay after seeing ads in the New York newspapers about the last frontier of Lake Minnetonka. By 1857, after making improvements to his property, Jennings permanently moved to the shores of the lake.

On the north side of Jennings Bay is a small point known as Skogbser Point. This point received its name from Eric Skogsbergh, who purchased the point from John Berquist in 1885. Skogsbergh Point became a summer cottage community for Swedish-Americans hailing from Minneapolis, St. Paul, and the surrounding region.

To the east of Jennings Bay and Harrison Bay is Lake Minnetonka’s West Arm, which is named after its relative geographic location on the lake. An island within the West Arm known as Deering Island is named after captain Charles Deering, who operated a small steamboat during the late 1800s in the West Arm known as the Florence Deering. The Florence Deering was an important steamboat in its day, serving the communities in the upper lake and West Arm region.

To the east, the West Arm narrows into a channel known as Coffee Cove (named after landowner C. C. Coffee) between Fagerness Point and the famous Lord Fletcher's Old Lake Lodge. Coffee Cove narrows further into the Coffee Channel, which connects to Crystal Bay to the east.

Crystal Bay receives its name for the deep, clear water within this portion of the lake. The bay is intersected by Bohn’s Point on its northern shore, named after Gerhard Bohn, whose house overlooked Crystal Bay from the southern tip of the point.

Crystal Bay has two different channels on its north shore that connect the bay to two other sections of the lake. The first of these channels on the northwest shore connects Crystal Bay to the North Arm, named after its geographic location on the lake. The second channel connects the northeast shore of Crystal Bay to Maxwell Bay, getting its name from John Maxwell, who settled the northeast shore of this bay in 1854.

Beyond Maxwell Bay to the north is the lake’s northernmost bay, Stubbs Bay. Stubbs Bay is named after Joel Stubbs and the Stubbs family, although the bay was known as Teas Bay and Bean Bay before its current namesake. The Stubbs family was large and owned large amounts of property throughout the Lake Minnetonka region. Like Peter Gideon on the south side of the lake, the Stubbs family was heavily involved in horticulture.

Heading back south and east through Stubbs Bay, Maxwell Bay, and Crystal Bay, one can take the Arcola Channel to reenter the lower lake. Immediately to the north of the Arcola Channel in lower lake is Smith Bay, which like Smithtown Bay, is named after the Smith brothers. Elliot Smith owned a farm that abutted the north shore of Smith Bay until James J. Hill purchased the farm in 1880. Hill used the smith farm to extend a railroad through the region to connect to Hill’s Lafayette Resort.

The eastern boundary of Smith’s Bay is the famous Brackett’s Point. Once called Starvation Point, early tales tell of Euro-American settlers at Minnetonka Mills finding the corpse of a French trapper who starved to death on the point in 1852. Without the appropriate tools to bury the body, the settlers returned to Minnetonka Mills to report their grim findings.

In 1880, George A. Brackett purchased the point to erect his new home. Stories suggest that when leveling the property, workers found the remains of the French trapper from decades prior. Here they gave the remains a proper burial at the tip of the point.

After Brackett’s home was completed, he chose to rename the point as Orono Point, after his home in Orono, Maine. Some older residents around Lake Minnetonka may still refer to the area as Orono Point, although more modern maps often use Brackett’s Point.

The last bay of this Lake Minnetonka journey is Brown’s Bay, borrowing the last name of James R. Brown. Brown first visited the lake while on an expedition with John Snelling and Samuel Watkins in 1852. Brown was a mainstay of the territory in these years; he had already attempted to claim land along Minnehaha Creek in 1826, later being removed by officers from Fort Snelling several times until he ultimately abandoned his land claiming attempts in 1830. When Brown came to the lake in 1852, he was given the land around this bay for under $10.

During those early years of Lake Minnetonka’s settlement, one early settler from Excelsior wrote, “we were no poorer than our neighbors and no richer.” Another settler from across the lake at Wayzata recollected, “there were no classes, all were on the same level.” Simply put, this is how the early Euro-American settlers of Lake Minnetonka liked to remember things. There certainly was a brief golden period when these early settlers were equal partners in the wild, rich years of the 1850s and 1860s.

Without context, it’s impossible to recall what life was like some 170 years ago. Life back then wasn’t static; changes came fast, furious, and unpredictable. Lydia Ferguson’s biography depicts scenes of love, despair, strife, and perseverance. Each settler was an individual, never were they some sort of caricature of pioneers repeating identical motions like a simulation of Oregon Trail. The early settlers of Lake Minnetonka met similar situations in as many ways as they were individuals. They were people.

This story originally appeared on The Minnesota Historian, the local history website run by Josh Biber.

Sources:

- Amy, Merton S.; Egan, James E. "Crane Island" Hennepin County Digital Library, 1907. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll17/id/928/rec/1

- Bennett, Helen Hunt. “Northome” Hennepin County History, Summer 1961.

- Carver, Jonathan. "Map Showing Jonathan Carver's Travels West of the Great Lakes" Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, 1766. https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:6108vw16z

- "Chimo", Hazen J. Burton residence, side view. Excelsior Lake Minnetonka Historical Society, 1895. https://mncollections.org/Detail/objects/54606

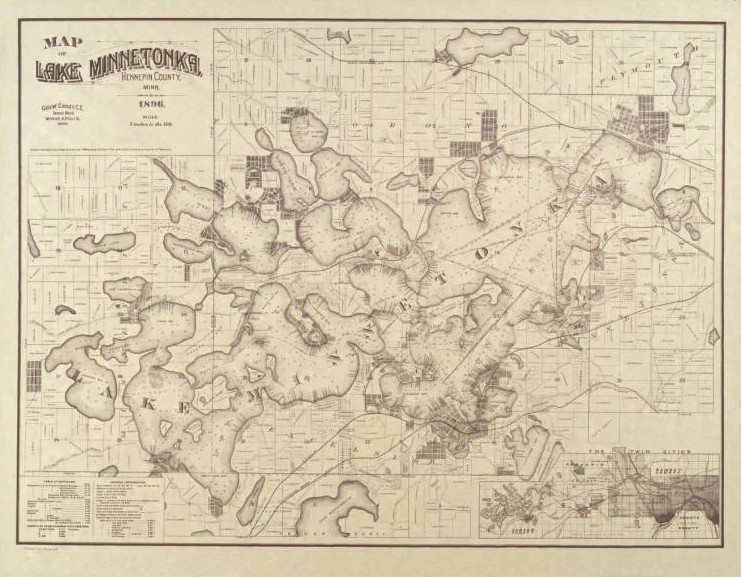

- Cooley, George. "Map of Lake Minnetonka, Hennepin County, Minnesota 1892" Minnesota Digital Library, 1892. https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/whs:197#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-2650%2C1072%2C13870%2C8647

- Eastman, Welles. “Starvation Point” Picturesque Lake Minnetonka, 1906. redistributed by Hennepin County History, Vol. 32 No. 3, Summer 1973.

- Illingworth & McLeish. "Spirit Knob, Lake Minnetonka" Minnesota Historical Society, 1870. http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10695836&return=count%3D25%26q%3Dspirit%2520knob%26tab%3Dresearch_items

- Jones, Thelma. “Once Upon a Lake; a History of Lake Minnetonka and its People” Minneapolis, Minnesota, Ross and Haines, Inc. 1969

- Kelley, Steve. “Reflections: On Stubbs Bay” SW News Media, May 8, 2012.

- "Lake Scene Goose Island" Excelsior Lake Minnetonka Historical Society, 1882. http://www.elmhsve.net/photos/virtualexhibit/vex13/2AC835E0-718B-4CD4-AF95-207904333192.htm

- "Katahdin, Swift's Point, Lake Minnetonka" Excelsior Lake Minnetonka Historical Society, 1899. https://mncollections.org/Detail/objects/314692

- "The Lafayette Hotel on Lake Minnetonka" Hennepin County Digital Library. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll18/id/206/rec/8

- “Major George B. Halsted Cremated in The Hermitage” The Minneapolis Tribune, September 7, 1901. P. 9.

- Matthews Northrup Works. "Tour map, Lake Minnetonka, Minnesota" Minnesota Digital Library, 1911. https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/msn:455#?c=&m=&s=&cv=2&xywh=-446%2C404%2C8285%2C4808

- McNight Christian, Carolyn. “Early Times… at Wayzata, Harrington Farms Orono, and Minnetonka Beach” Hennepin County History, Fall 1960.

- Meyer, Ellen Wilson. “Dairying Around Lake Minnetonka” Hennepin History, Vol. 36, No. 3, Fall 1977.

- Meyer, Ellen Wilson. “Our County’s Fruit Basket” Hennepin History, Vol. 34 No. 4, Fall 1975

- "The Narrows, Lake Minnetonka, Minn." Excelsior Lake Minnetonka Historical Society, 1920. https://mncollections.org/Detail/objects/327688

- "Olaf O. Searle House, Big Island, Lake Minnetonka" Excelsior Lake Minnetonka Historical Society, 1905. https://mncollections.org/Detail/objects/259297

- Olson, Mark. "Lake Shore Drive, Phelps Island, Mound, MN" Excelsior Lake Minnetonka Historical Society, 1920. https://mncollections.org/Detail/objects/320572

- "Passing from Lower Lake into Crystal Bay on Lake Minnetonka, Minnesota" Minnesota Digital Library, 1900. https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/whs:163#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-2118%2C-1056%2C8268%2C5155

- Sohns, Brad. “Three Points - Finding its History and Heart” Westonka Historical Society, October 11, 2022.

- "Steamboat Belle of Minnetonka" Excelsior Lake Minnetonka Historical Society, 1884. https://mncollections.org/Detail/objects/257362

- "Streetcar Boat Harriet" Excelsior Lake Minnetonka Historical Society, 1920. https://mncollections.org/Detail/objects/282207

- "Streetcar Boat White Bear at Shady Island" Excelsior Lake Minnetonka Historical Society, 1906. https://mncollections.org/Detail/objects/327799

- Stubbs, Avery. “The Quaker Settlers from Ohio and Indiana” Hennepin History, Summer 1950.

- Stubbs, Avery. “New Sweden… In Western Hennepin County” Hennepin History, Summer 1961.

- Sykora, Barbara McHenry. “Charles Gibson’s Lake Minnetonka Summers” Hennepin County History, Vol. 72 No. 3, Fall 2013.

- Upham, Warren. “Minnesota Geographic Names; Their Origin and Historic Significance” Minnesota Historical Society, 1920

- Wright, Nellie B. “Linwood - Lake Minnetonka” Hennepin County History, Vol. 8. No. 30, April 1948.