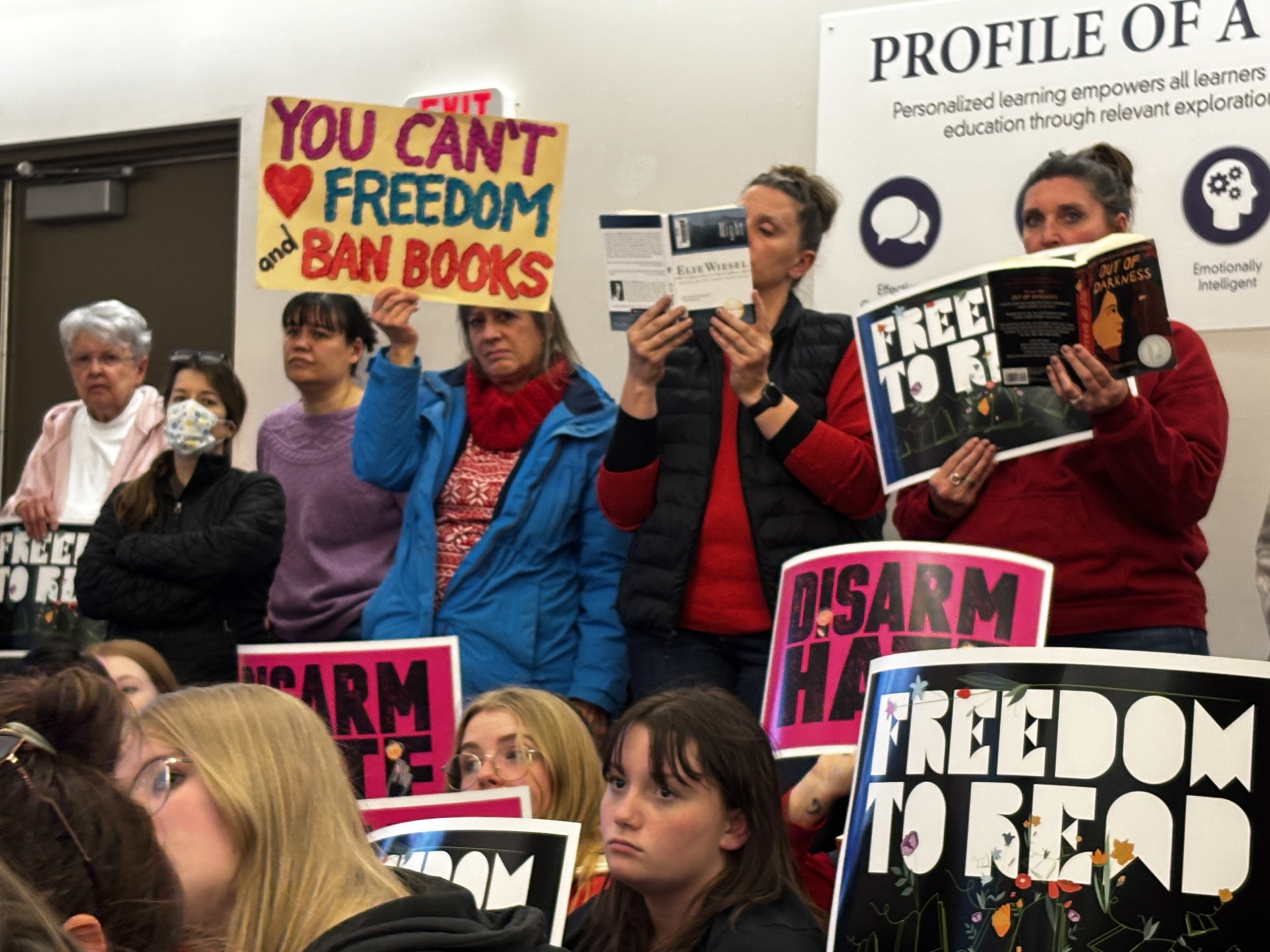

On a Monday night in late March, dozens of St. Francis Area Schools students, parents, teachers, and community members cram into a small district office for a school board meeting. Most are wearing the same red shirt.

Four months earlier, the board had passed policy 606.5, which directs the district to use the conservative website Book Looks to remove books from its school libraries if the content is deemed offensive. The measure passed by a 4-3 vote, with only a sparse crowd observing from inside the beige, fluorescently lit room.

This night, however, a packed crowd of more than 100 shows up wearing the red shirts made by Parents for the Freedom to Read, a group launched in the St. Francis school district by parents who want the board to rescind the policy—or the book ban, as they call it. Students and teachers alike have been wearing these shirts to school, around the community, and to the gathering tonight.

The meeting begins with the awarding of the “Saint Star Award” to four students, including Nathanial Esboldt, who withstands the applause uncomfortably. Then School Board Chair Nathan Burr announces that board members won’t be discussing the policy at the meeting or with the media. The reason? Both the ACLU of Minnesota and teachers’ union Education Minnesota-St. Francis had filed lawsuits against the district.

The room falls quiet as Burr addresses the suits. His announcement briefly takes the wind out of the crowd, who are there to release an anger that has grown in the months since the policy was passed.

During that time, outraged community members lambasted the policy, creating a tense atmosphere in the north exurban school district of around 5,500 students. Until that night’s meeting rumors of lawsuits had swirled; union teachers had implored the board to kill the policy before they took legal action. But the books were removed, the policy remained in place, and legal blowback indeed followed.

For those who came to the meeting to criticize the policy, the board’s refusal to discuss the subject proved disappointing. But it didn’t stop them from speaking out.

Over the next two hours students and community members take the stand to debate the book ban without input from the board. Of the 33 speakers, 29 call for the removal of the policy, to raucous applause of the red-clad attendees. (Meanwhile, the ban’s supporters—all four of them—politely cheer for one another.)

“This isn’t about losing books. It’s about losing the ability to learn without fear,” Julian Kelcher, senior class president of St. Francis High School, tells the board.

Opponents read letters from writers like Ashley Hope Pérez (author of banned book Out of Darkness), Shaun David Hutchinson (author of We Are the Ants, which would be prohibited under the book ban policy), and Elana K. Arnold (author of What Girls Are Made Of which, you guessed it, would be banned by this policy). They emphasize the importance of freedom of speech, and express concern over students’ education if these books are removed. Whenever someone speaks from the podium in favor of the ban, much of the crowd covers their faces with open books in protest.

Before the policy was passed last November, St. Francis was already beset by below-average middle school scores and youth mental health concerns. For many residents shocked by the idea of banning books from their school libraries, rallying against the policy became a point of comfort, a way to find a greater voice to advocate for their ability to read freely. As the lawsuits proceeded through early 2025, the fury grew. At the April board meeting, more came to condemn the board—including Esboldt.

“How can you say that St. Francis Area Schools is properly preparing its students to be responsible citizens in a dynamic world,” Esbolodt, the St. Francis High School senior, asks the board, “when these very real topics are being removed and hidden?”

Though their district is represented by Republican U.S. House Majority Whip Tom Emmer and has voted for Trump each of the last three elections, many residents of Anoka and Isanti counties outright rejected this politically motivated policy. Parents, students, teachers, and two lawsuits fought against the ban, originally passed under the guise of appealing to the conservative leanings of St. Francis, for seven months. Eventually, through grassroots organizing and some legal leveraging, they killed the book ban, which was reversed earlier this month.

Here is how they did it.

How the Books Got Took

I wasn’t a particularly great student during my time at St. Francis, where I attended public schools from kindergarten through high school. Still, the books we read, discussed, and wrote about were just about the only things that could hold my attention for more than a few minutes. If you’d told me that the school district would be removing books from the libraries just six years after I read Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 for my AP Language and Composition class with Glenn “Mo” Morehouse Olson, a teacher who gave me my first crack at writing for the student newspaper? I would’ve written you off as a loon.

But in communities across the country just like mine, book bans are being pushed by an “increasingly influential constellation of conservative groups,” as the New York Times phrases it.

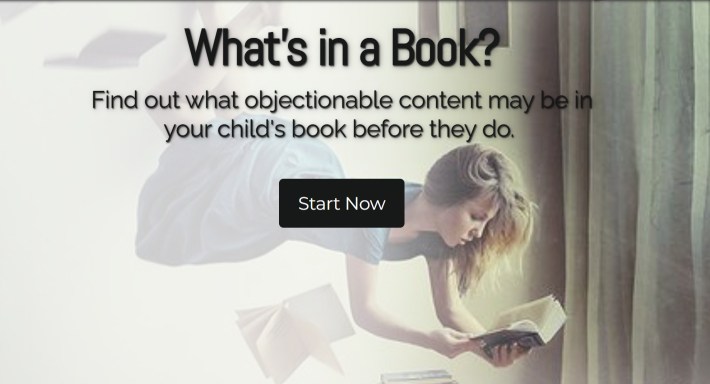

Policy 606.5 was first introduced late last September by ex-Board Member Amy Kelly, and it echoed similar policies around the country. Kelly championed the ban as a way to remove “pornographic” and “obscene” content from school libraries; any book with an obscenity rating of three or higher on the website Book Looks, whose rating system goes to five, would be eligible for removal from the libraries. The content rated at a three or higher usually has to do with race, violence, drugs, or sexual activity. Coincidentally, the website ceased operation and removed its ratings the day before the contentious March board meeting, but you can still find them with the trusty ol’ Wayback Machine.

Have violence or drug abuse in your book? That’ll get you a three. Throw in some bestiality and sadomasochism? That’s a five (think Fifty Shades of Grey, which received a five.) If your book has explicit hate in it, that’s a three, but it is only a two if it contains “moderate” hate. Speaking of seemingly arbitrary distinctions: Your book will get a one if it has “inexplicit gender ideologies,” though it’ll be upgraded to a two if it contains “explicit gender ideologies.” The latter distinction was likely thrown in there to punish books that feature transgender people, but mostly reads as vague and nonspecific.

Book Looks was formed in 2022 by members of the right-wing group Moms for Liberty, one of the organizations pushing for book bans across the country. In 2022, the Southern Poverty Law Center labeled this self-proclaimed “parental rights” group as extremists. The group fought to undermine COVID regulations and suppress discussions of race and LGBTQ+ issues in schools.

These types of groups, some of which are backed by billionaire activists like the Koch brothers, target local elections like school boards to push for more conservative teaching standards and to shield students from scary topics like “race” and “gender.” At least 50 book-banning groups have spiderwebbed across the country in recent years, according to a report by free-speech org PEN America; between 2023 and 2024, bans surged by almost 200%. Almost half of the banned or challenged books include the voices of LGBTQ+ folks and people of color, according to the American Library Association. “This crisis is tragic for young people hungry to understand the world they live in and see their identities and experiences reflected in books,” PEN America’s Kasey Meehan said last year.

A new Minnesota law shields schools and libraries in Minnesota from many of the actions of book-banning groups like Moms of Liberty. Last August, the Access to Library Materials and Rights Protected statute effectively banned book bans in Minnesota. Under this new law, you can’t remove a book from a library just because you disagree with its ideas. A library could limit access to or decline purchase of a book because of inappropriate subject matter (the reasonable we-still-probably-shouldn’t-have-porn-in-the-library clause), but a licensed media specialist, professional librarian, or someone with a master’s degree in library science must must oversee book selection and evaluation. Unfortunately for the St. Francis School Board, Book Looks lacks all of those qualifications.

In St. Francis, the book ban vote was pushed back twice due to debates over whether Book Looks should have authority over district libraries. The site shut down the day before the March meeting, and it was unclear how the policy could stay in place without it. Some teachers told Racket that if you can prove a given book earned a rating of three or higher via Book Looks at the time of its closure, the book could still be removed, but they weren’t entirely sure. Several board members who voted in favor of the policy are no longer on the board today. Burr, however, is still around. He voted against the policy due to its reliance on Book Looks, citing fears of a potential lawsuit and an overstep on the board's part.

One of the books slated for removal was Night, Elie Wiesel’s harrowing memoir of surviving the Holocaust. “That’s telling me that we would not want to have a book in our library that is a true story of a Holocaust survivor,” Burr said. He feared that books like The Diary of Anne Frank (which I read in 8th grade English) would be next to go.

Yet the proposed policy kept gaining traction.

At an October meeting, one month before the policy passed, then-Board Member Pamela Johnson read from some books she sought to remove from schools. One was from Sold, about a young girl sold into prostitution. Johnson read a passage in which an old man rapes the girl. She then read passages from Tricks and The Bluest Eye, which included sexual assault and sexual activity.

“We don’t expect them to talk that way in school, yet if we provide the books in the library, we are pretty much sanctioning it,” Johnson said minutes before voting to approve the policy a month later.

As a Christian, Johnson said, she brings a theological perspective to the table when making decisions for her community. After reading passages from those books, she also read passages from the Bible—no violence against women there—meant to guide the board in their decision-making.

Flaring Tensions, Mobilizing Lawyers

Months after Pamela Johnson read from those bannable books, stoking a moral panic over classroom reading materials, Ryan Fiereck says the pro-ban tactics started growing more and more manipulative.

“No one wants to hear the word ‘pussy’ yelled out or the ‘F’ word,” says Fiereck, local president of Education Minnesota-St. Francis and a teacher in the district. “That's not what these books are about, but they can sure make people feel uncomfortable and then make them leave their common sense solutions to just go with whoever was kind of pressuring them at that time.”

Fiereck was one of the few people in attendance for the October 28 meeting. He tried to get parents, teachers, and board members to oppose the policy for months before it was enacted, but to no avail. Public awareness didn’t really exist until after it was approved, he says. As a teacher in the union, Fiereck has been attending school board meetings for the last 15 years. Union teachers are often the only people in attendance, he says.

Fiereck, his partner, and his children were plaintiffs in the Education Minnesota lawsuit. Filed on behalf of eight students whose parents are teachers, the suit pushed to have the books removed from school libraries reinstated and the policy declared illegal under the Access to Library Materials and Rights Protected I mentioned earlier.

You might think the policy merely reflected the area’s political realities—that’s what Kelly said while arguing for the ban last fall.

“We’re red here, just to let you know,” she said during the November 25 meeting. “We may not always be on the same page, but we are conservative. They don’t want this stuff in the libraries.”

But Barb Anderson, a member of Parents for the Freedom to Read, rejected Kelly’s shoehorning of partisan politics into the classroom curriculum.

“You can listen to many a school board meeting that I have spoken to the board saying, when your name was on the ballot, there was no affiliation after your name. No, R for Republican, no, D for Democrat, no, I for independent, there was nothing there,” she tells Racket.

“We cannot say for certain that every community member wants to use Book Looks,” Burr said. That meeting was the last of the previous board, and only four members returned for the next term. Starr, Kelly, and Johnson did not run for reelection.

Some community members spoke up in favor of the ban at board meetings. Richard Klabachek, 72, recommended the book It’s Perfectly Normal for removal from school libraries. (He insists it be called “book removal” instead of a “book ban” policy.) Klabachek described the book as “pornographic”; the book’s authors describe itself as a sexual health primer for children above the age of 10. It’s Perfectly Normal, which has been frequently banned since its 1994 release, contains illustrations of naked people and covers sex, gender, sexual abuse, birth control, and other topics that reliably freak out conservatives.

The district has never provided teachers with a full list of books that were removed from the library. It’s unclear whether It’s Perfectly Normal was even in the library to begin with.

Olson, my former St. Francis High teacher, tells Racket she and other teachers were unable to find an actual list of books that were removed or slated for removal. Instead, they’d learn in real-time as books vanished from the library. She says that confusion made everything more difficult for students and teachers.

“I taught Kite Runner. I've taught Night by Elie Wiesel,” Olson says. “I teach others that might be on that list… I guess I'm not looking to comply in advance.”

The Kids Become the Adults in the Room

The day of the March meeting, St. Francis High School sophomore Isabel Baumgart and some of her classmates organized a walkout. Around 100 students stepped out of the school around 1:20 p.m., sat in circles in front of the school, and read books.

St. Francis High School senior Sophie Edwards brought The Hate U Give and Dear Evan Hansen from her personal library. Both books scored threes on Book Looks, making them eligible for removal. She said others brought books like Me, Earl and the Dying Girl, The Handmaid’s Tale, and The Bluest Eye, among other titles deemed potentially dangerous to young minds. All three of those books were removed from St. Francis school libraries.

Edwards and the rest of her circle passed around The Handmaid’s Tale and read it aloud. She says it was the first time she’d read the book in years.

“Reading it out and just remembering all the details of their living situation and the mentality and how they seem so broken at the beginning just definitely really hit close to home,” Edwards says. “Because just seeing this group of people broken down, so settled into a way of life that is not OK for anybody to have to live through, was very intense to be sitting trying to stop that exact thing from happening.”

Julian Kelcher, the senior class president, says more students walked out of school than he expected. He was surprised by their passion—those 100 protesters represent about 10% of the total student body.

“I was sitting in a circle with a bunch of people who I knew, and I didn't know that they actually really cared about their education—and I don't mean to be rude towards them at all,” Kelcher says. “I thought they would show up just to show up, but they were actively listening and reading.”

Baumgart, Kelcher, and Edwards all spoke at the school board meeting later that day. Wearing a red shirt from Parents for the Right to Read and socks that read “Books turn muggles into wizards,” Baumgart took to the podium to plead with the school to rethink the policy. She emphasized how books help us understand our complex, messy world. Finding the time wasn’t easy: Baumgart, who is playing Yertle the Turtle in the school’s upcoming production of Seussical the Musical, and her classmates spoke again at the April meeting before racing out to get back to theater practice.

“It definitely helps that me and a lot of people who spoke are in theater, so we're used to speaking in front of an audience, so it wasn't as stressful in that way,” Baumgart tells Racket. “But just the idea of how many people were also in the room that did not agree with what I was saying was a little scary.”

Though the board’s decision to remove books from the libraries stirred plenty of unease, community members report the resulting fight against censorship has proven inspiring. When Edwards pleaded with the board to reconsider their decision at the meeting in March, she struggled to hold back tears. As she addressed the board, students around her stood in support.

“I originally brought it to my theater department because I had a rehearsal, and I just gave a quick thing about like, ‘Hey guys. Like, before I start anything, I'm planning on attending this meeting, I would really love your support,’” Edwards says, adding that several banned books were included as part of AP testing prep guidelines. “There were 13, 14 people right away who were like, ‘Yeah, Sign me up.’”

Both donning red, language arts teachers Mike Stoffel and Olson called for the board to adopt a new curriculum at the start of the April board meeting. Olson, who also spoke against the ban at the March meeting, said the curriculum hadn’t been updated since she started teaching in the district 22 years ago. Neither spoke of the ban that night, but Stoffel, his wife (and fellow teacher) Alicia Stoffel, and their child are plaintiffs in the Education Minnesota suit.

“As students, our options for learning have been taken away,” Baumgart says.

At the October board meeting, where she read from several books to push for the policy, Johnson said there is a mental health issue in St. Francis schools. She blamed the lewd content of undesirable books in addition to cultural desensitization to violence.

She’s not wrong. About the mental health issue, at least. “I feel like there's so much that the school could be doing, and that it just kind of isn't,” Kelcher says.

Kelcher is a member of Students Against Violence Everywhere, or SAVE, a youth leadership group from Sandy Hook Promise that aims to empower students to keep their classmates and community safe. He says one of their goals is suicide prevention. Just before spring break, a St. Francis High School student committed suicide. When I attended St. Francis High from 2017 to 2021, seven students died, three of them by suicide.

Students and community members Racket spoke to were concerned that removing these books limits the resources students have to deal with or learn about issues like sexual assault, racism, or gender identity. Further, Mo was disappointed that, instead of putting more time and effort into helping students struggling with their mental health or grieving the loss of a classmate, the board decided to legislate libraries instead.

With several recent deaths in the community, Kelcher says the high school had already become a tense place without the drama of the book ban. The policy and the fallout surrounding only fanned those flames. When speaking to the board, Baumgart emphasized how important books can be to understanding the world and yourself.

“What's in a lot of the books really helps people, where it makes them feel like they belong, or makes them understand other people's perspectives,” Baumgart says. “And if those options are being taken away, it's like showing the students that they're not allowed to feel comfortable, or they're not allowed to feel safe, and they're not allowed to know anything that they want to know.”

Beyond the serious issues impacted by the ban, many residents felt it simply defied common sense. My family lived in the St. Francis school district for over 20 years, and my parents are a fairly typical St. Francis couple. My dad is a blue-collar contractor for Window World, and my mom is a nurse. Both would probably tell you they lean conservative. They might even recite the “fiscally conservative, socially liberal” mantra and mean it.

Walking through the woods a few days before the board meeting in April, my dad asked what was going on with the book ban. When I told him, he laughed.

“What are they gonna do next?” he asked. “Ban dancing?”

“Books Have Changed Their Lives”

On May 5 students and community members, including Baumgart and Olson, gathered inside the cavernous brick St. Francis United Methodist Church, where Dave Eggers, author and founder of the literary humor website McSweeney’s, and journalist Amanda Uhle spoke during a community forum about the book ban. In 2017, those two high-profile literary talents founded The Hawkins Project to support student writers around the U.S.

St. Francis High School junior Olivia Hagerty grabbed the microphone to talk about the ban and how important one of the banned books, The Hate U Give, was to her as a Black student in a mostly white community.

“It’s really amazing and awesome to see all these people supporting us and helping us,” she told Fox 9. “And we aren’t doing this alone.”

Olson says the editor of The Hate U Give was at the gathering, along with several other authors and editors. That editor was so touched by Hagerty’s remarks, they’re working to put her in touch with Angie Thomas, the book's author.

“This is the kind of thing that they were talking about,” Olson says. “These kids are talking about how books have changed their lives.”

In April the school board announced it would seek legal settlements, and earlier this month, the board reached ones with both Education Minnesota and the ACLU. A new policy will utilize parents and media specialists to determine if a book is appropriate rather than a politically charged rating system from a defunct website. Effectively, the book ban was no more.

Before the meeting, Parents for the Freedom to Read held a potluck outside of the district office. They’d caught wind of the settlements before the public, and had gathered for some support, speculation, and of course, good grub.

“We could feel the energy,” Parents for the Freedom to Read’s founder Nikki Kruse-Dye says.

Kruse-Dye says 25-30 people showed up for the potluck, and even more rolled in for the start of the meeting. Unfortunately, not many students were present for this one. Many were off at the Spotlight Showcase awards for theater with Olson.

Olson had just won theater educator of the year, and on the bus ride home, she heard the news that the ban had been officially overturned. Crammed into a school bus over a week after their last day of school, the students cheered.