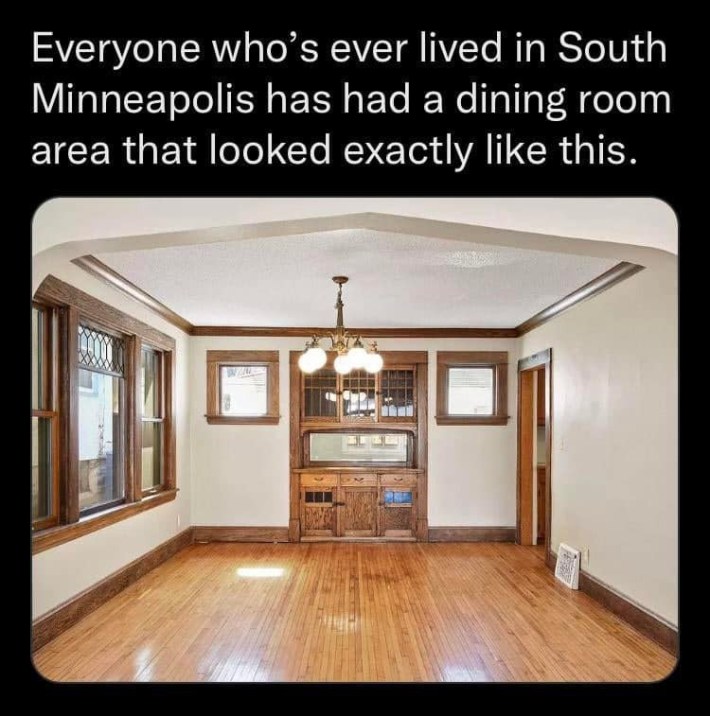

A local meme began making the rounds last week, as is the nature of memes. In it, we see a classic south Minneapolis dining room—oak hardwood flooring, built-in buffet, piano windows, crown molding, leaded glass.

See for yourself:

The relatability metrics, so crucial to meme virality, proved off the charts. Hilariously, however, internet property sleuths revealed that the home depicted in that photo is actually located in Northeast. (You can buy it for $300,000.)

But this particular image would resonate almost anywhere in the country. It's an example of the Arts & Crafts architectural craze that hit the U.S. in the early 20th century, explains architectural historian/writer/bassist Dick Kronick, specifically the closely associated bungalow style.

While the ubiquity of that room might not be unique to south Minneapolis, it still powerfully connects with the many locals who've lived in spaces like it. Especially, Kronick says, in an age of soaring home unaffordability and plummeting construction quality.

"It symbolizes quality work. It symbolizes doing financially well. It symbolizes family life," says Kronick, who serves as a board member with historical preservation group Preserve Minneapolis. "It has a whole lot of submerged stimulators of endorphins in your head. You subconsciously associate it with all these warm, fuzzy thoughts. That’s what it’s about."

Since we had an expert on the phone to explain dumb memes to us, we took advantage and picked Kronick's brain about everything related to the highly relatable south Minneapolis bungalow.

On the origins of “bungalow” in India and England…

"The word "bungalow" originates from India, the province called Bengal. And a bungalow actually just means a dwelling in Bengal, originally. Of course the English ruled India for a long time, and they brought back the name bungalow to England and transformed it in the late 19th century, during the Arts & Craft movement—William Morris, John Ruskin, people who were radically rebelling against historic architecture, architecture that seemed irrelevant. They were also, very strongly, reacting against the Industrial Revolution, which concentrated people in cities—the population of London quintupled. People were crowded, squalid. Charles Dickens’ novels are the touchstone there."

On the evolving meaning of bungalow…

It’s now associated with a certain floor plan. My 1932 south Minneapolis house is what a real estate agent would call "Tudor Revival." And I had a mentor in the '90s, a very eminent architectural historian, who scoffed at that phrase. He said, "A better name for these houses is 'English Cottage Fantasy Revival.'" But as far as the layout of the rooms, it’s a bungalow. That simply means that the front door opens into the living room, and then partial sidewalls divide the living room from the dining room, and then there’s a doorway into the kitchen. You have those three rooms lined up on one side of the house, then there’s a structural wall dividing the other half—almost always a bedroom, a bathroom, and another bedroom.

On craftsmanship mattering…

Bungalows became intertwined with the Arts & Craft movement in the early 20th century. People like Morris and Ruskin wanted, instead of the cheaply made industrial goods flooding the market, to return to craftsmanship. Look at the lovely oak built-in buffet you sent over. What does that mean to us? It means craftsmanship. Just look at that thing, and it makes you happy that someone had the skill to do that. What does that mean emotionally and psychologically to people? It’s reassuring to us. It makes us happy, it makes us feel like human activity is worth something.

On the '20s and '30s south Minneapolis building boom…

Of course, the Great Depression brought it all to a halt by about 1935. That was the last gasp of the building boom; there are very few houses built anywhere in the United States in the last half of the '30s. The '20s were the roaring '20s, a period of great expansion. It was the second-fastest decade of population growth in Minneapolis after the 1880s. The part of Minneapolis that you and I live in was really built in the '20s and the first few years of the 1930s. At the same time, Theodore Wirth was building Minnehaha Parkway, dredging Nokomis and Hiawatha, creating all the parkland, which now is part of the Hiawatha Golf Course dispute.

On the nationwide ubiquity of that classic south Minneapolis dining room…

The dining room from that meme exists almost anywhere in the U.S. with a housing stock built during that time. There are Arts & Crafts bungalows across the nation, it was a huge fad. It really gained steam after World War I, because materials were needed for the war effort. That pent-up demand exploded into a building boom of Arts & Crafts bungalows. Homebuilding didn't really pick up until after World War II, by which time the fad had long passed. Modernism came next. Starting in the 1940s, you have houses that are miniature versions of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie School—the suburban rambler. Go out to Richfield and it’s just one after another. They’re a reflection of Frank Lloyd Wright’s idea that a house should hug the land. In my way of thinking, a sad change. Because the whole idea of craftsmanship was lost.

On build quality then vs. now…

I’m usually pretty depressed to see newer construction homes. A lot of the stuff is shoddily built. In 50 years, those buildings will be in very poor condition. I’m sitting here on an oak floor, the brick in my fireplace… I don’t know how you could afford that as a lower- to middle-class person today. Oak, the hardest wood that was plentifully available, was cheap. Nobody cut down forests in the 1920s or '30s gave a shit about replanting, there were no government restrictions on them to speak of. That was just the very beginning of the National Forest program to put some sort of order on the cutting of trees. That’s another part of why housing was cheaper for middle-class people: nobody cared about the environment, so they could afford better materials. You could say the idea of revering craftsmanship was utopian and impractical. It was possible because the carpenters and plasterers and all the tradespeople of the '20s were working for nickels, for dimes. Their pay was shockingly small for they did, and they ceased to exist by the ‘40s.

On early 20th century class-conscious construction…

There’s a subtle class distinction. There’s a progression as you go through a house from public areas—the living or dining rooms, where you’d entertain guests—and then your kitchen is more private, often separated by a swinging door. The point is, people of middle-class means who’d own south Minneapolis houses in the '30s, could afford a cook or a maid. It was very common. So you closed off the kitchen so you could keep the heat, and the person who was not part of the family, in that separate space.

Want to hear more about houses from Kronick? He'll be teaching an online University of Minnesota course called "What Style Is That House?" on June 7 and 14; more info here.