When a machine doesn’t work, most of us get frustrated. But for Howard Freeman, a broken machine presents an opportunity.

“I used to fix things when I was little,” he says. “Got in trouble for taking stuff apart once in a while and putting it back together.”

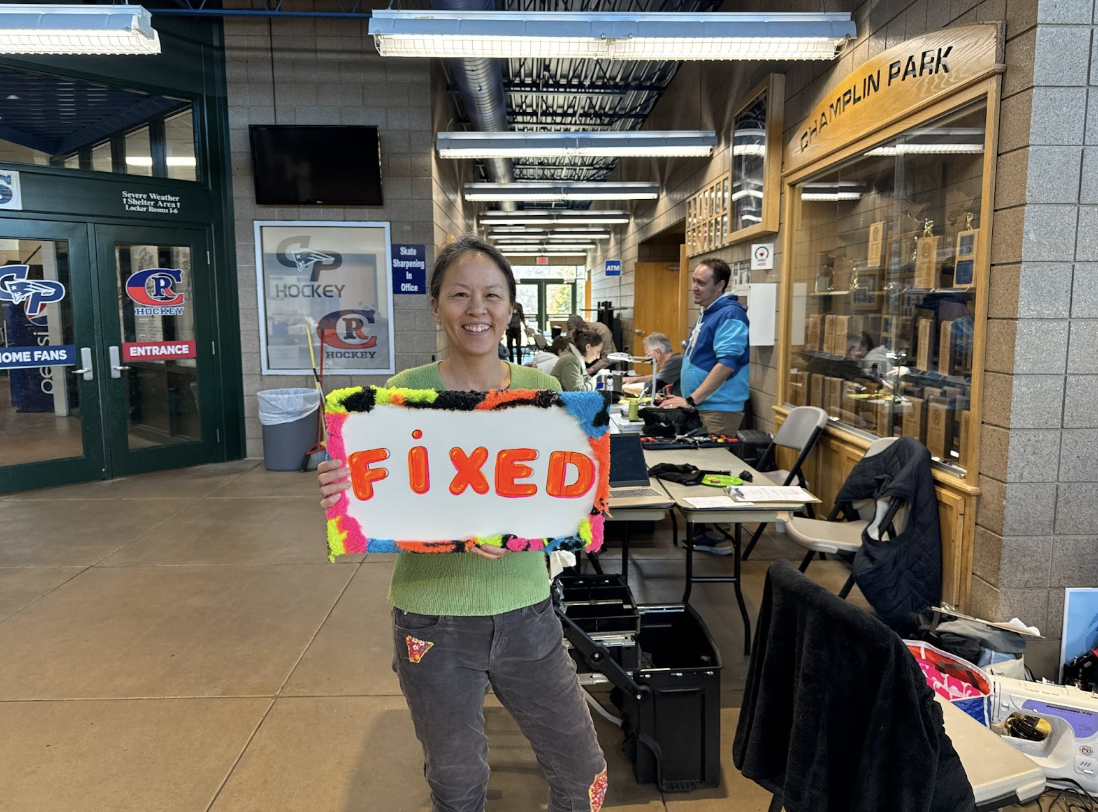

Freeman is a longtime volunteer at Fix-It Clinics around the Twin Cities, where anyone can bring almost any kind of broken stuff to these free events, and volunteers will try to repair it. At the March clinic in Champlin, for instance, items that needed fixing included a printer, a weed-whacker, and even low-tech items like blue jeans.

Nancy Lo, the program coordinator for Fix-It Clinics in Hennepin County, says she got the idea from a New York Times article about a similar program in Amsterdam. “I have stuff that’s broken, and I don’t know how to fix it,” Lo says she thought. “And I don’t know how to fix it, But I know it can be fixed. So I was like, ‘Hey, maybe I can get my broken stuff fixed if I start this program.’”

But for years, these clinics have been limited in their ability to fix newer electronics, in part because many manufacturers only make parts or manuals available to authorized repair shops. That will change this July 1 when a new state law, called the Digital Fair Repair Act, goes into effect.

This law will require the manufacturers of certain electronic devices sold after July 1, 2021, to make repair manuals available and to sell the parts needed for the repairs. This law is part of the global “right-to-repair” movement, which seeks to make it easier for people to fix electronics without the approval of the manufacturer. Right-to-repair activists have praised the Minnesota law for covering more devices than any other state. (Some exceptions remain, like farm and medical equipment and video game consoles.)

Gay Gordon-Byrne is the executive director of the Digital Right to Repair Coalition, a trade group that represents businesses such as repair shops. She says that in recent years, tech companies have made their products harder and harder to repair, both through physical design and through changing contracts. According to Byrne, many people today sign away their right to repair their own electronics, or to take them to a repair shop not approved by the manufacturer, before they even start using the device.

“You lose the right to repair if you make an agreement saying, ‘OK, I won’t fix my stuff,’” Byrne says. “The problem is, all of that negative stuff is provided to you in a contract you can’t negotiate, often called an end user license agreement.”

This is the massive wall of text that you have to click “agree” on in order to use a new device, which most people understandably never read. The new law gets around this by requiring manufacturers to make parts and manuals available to the public, rather than just their own shops or shops that have a special deal with them.

Not everyone is as enthusiastic about right-to-repair legislation. Kristian Stout is a programmer and lawyer who is the director of innovation policy at the International Center for Law & Economics. Stout loves to tinker with computers, but he’s not convinced that the right to repair makes sense for people who aren’t as technically inclined.

According to Stout, restricting repair to shops that have a special deal with a manufacturer can mean more peace of mind for consumers, because not every shop will have the resources to protect consumer data. “There’s more incentive for smaller firms to actually not invest as much in cybersecurity and data privacy,” he says.

Stout uses the example of Apple, which keeps a tight lid on its repair network in order to protect their business. “They want to make sure that consumer devices and data, specifically, are protected.” He adds that this isn’t just out of the goodness of their hearts, either—big tech companies want to protect their own brand by preventing things from going wrong with their devices.

“It’s a double-edged sword, too, putting requirements on manufacturers and designers,” says Cory Brown, a product designer and Fix-It Clinic volunteer. He explains that requiring manufacturers to provide manuals and parts “could make the designer process a little bit more expensive, it will make the manufacturing process more expensive.”

Volunteers and staff at Free Geek Twin Cities, a Minneapolis-based nonprofit that refurbishes old tech and sells it back to the community at affordable prices like aspects of the new law, although it probably won’t affect them for a while since, like the Fix-It Clinics, they mainly work with older devices.

“The vast majority of the stuff that we work on at Free Geek is not covered by the new legislation,” says Erin “Stevie” Stevenson, who works in store operations and outreach at the organization. But she adds: “It’ll be really good for the years to come as we keep getting more and more new stuff.”

Thanks to places like Free Geek and the Fix-It Clinics, right-to-repair laws may make a real change in how people think of their electronic devices. Volunteers and clients said that while the Fix-It Clinic’s price tag (or lack thereof) was attractive, the community spirit of the event was also a draw.

“There’s quirky people here,” says Sarah Moberg, who came to the clinic to get her mom’s printer fixed. “I like the community feel about it, rather than the capitalist feel of the [Best Buy-owned] Geek Squad.”

“I come here, wherever they’re at, every month, just to socialize,” says Ron Wells, a retired electrician and regular client.

You don’t have to be located near a Fix-It Clinic to get involved. Peter Mui, who has helped start clinics around the country, runs a Discord server where people around the world can help each other with repairs. “You tell them you have that problem with your laptop, and they’re, like, ‘oh, OK, here we go,’” says Molly Sanford, the operator of a clinic in Marine on St. Croix, Minnesota. “It’s an exciting problem for them to help you solve.”

“Fix-It Clinic is really more about empowering people,” Mui says. “The gift we’re giving is not the repair. The gift we’re giving is critical thinking and troubleshooting skills.”