Lurking in the dark underbelly of the Twin Cities lit scene (just where they like it), small-press horror publishers are pushing the genre forward in strange new directions. These are often one-person businesses, run out of small studios or apartments, where extra rooms serve as storage space for back catalogs.

But with that smaller size come benefits: fleetness, boldness, and a willingness to challenge the conventions of the genre in ways that the Big Four publishers can’t.

“There’s no committee, there’s no board that all has to approve anything,” says Sam Richard, owner and publisher of Weirdpunk Books. “I just want to put out books that I love, sometimes books that got rejected from other places because they were too weird or didn’t fit some standard vibe. It's not this lumbering machine with all these parts that need to move, it’s just me and the author putting it together and getting it out into the world.”

After working as an editor with founder Emma Alice Johnson, Richard took the reins at Weirdpunk in 2018. Founded in 2015, Weirdpunk once featured the “punk” element more prominently. All their early titles were short-story anthologies themed around music, including literary tributes to GG Allin, the Misfits, and an anthology called Zombie Punks Fuck Off.

“I come from punk, I played in punk bands,” Richard says. “But the most important aspect of it to me has always been the DIY spirit, egalitarian culture, and radical politics.”

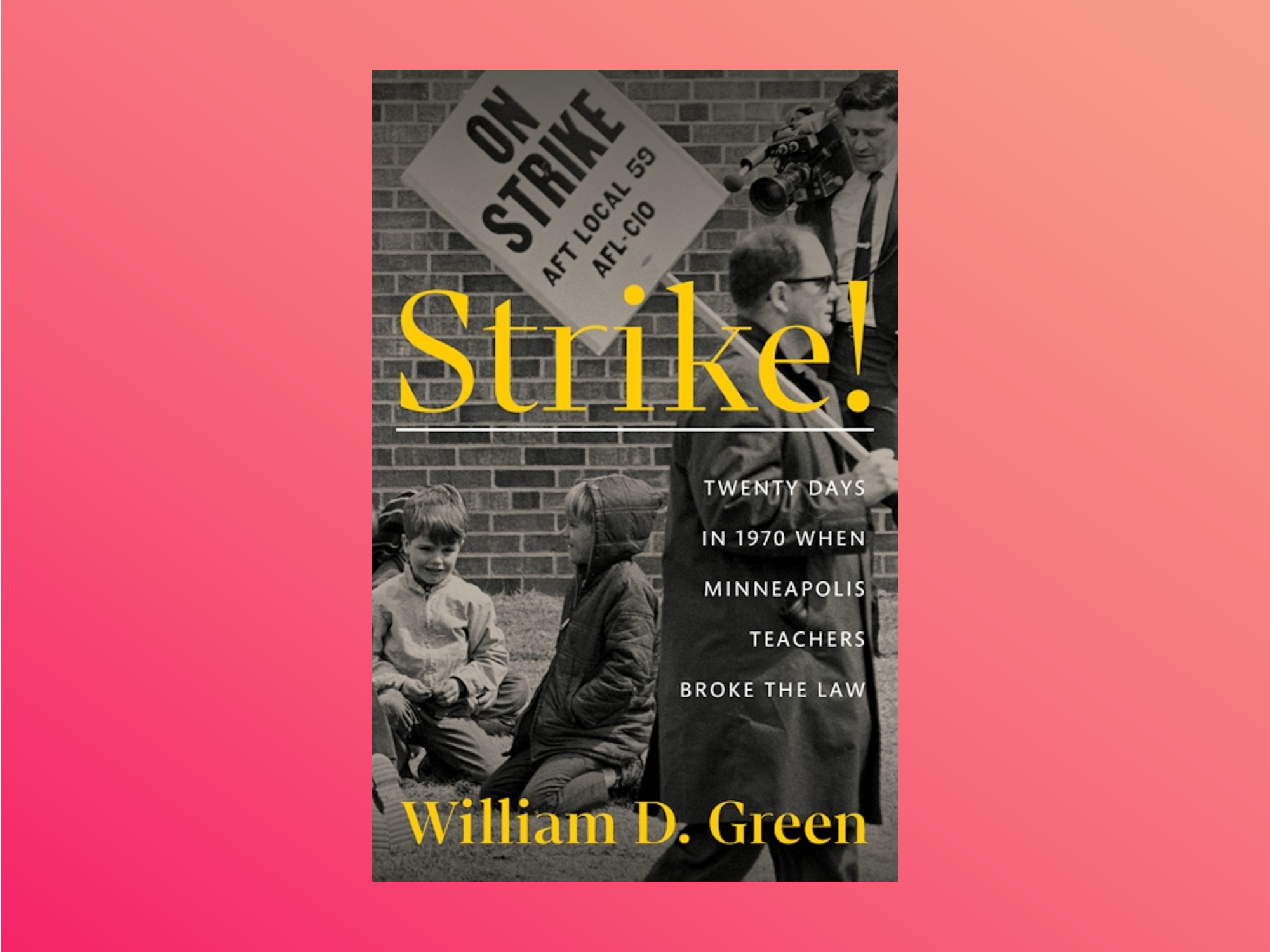

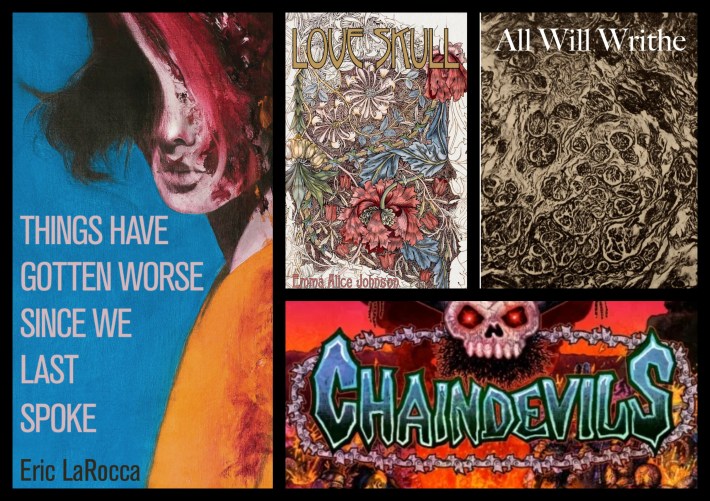

Since those early days, Richard has shifted his focus to “weird” fiction with broad punk associations and queer horror, with dedication to publishing more novellas and single-author work. He’s been an early supporter of up-'n'-coming writers like Jo Quenell and Joe Koch; published Things Have Gotten Worse Since Last We Spoke, Eric La Rocca’s breakout hit; and, in November, Weirdpunk will release its 27th title, a collection of Richard’s own short stories.

Small-press distributor Asterism has been a boon in helping get Weirdpunk’s work to independent booksellers, who are his ideal partners.

“As both a publisher and a writer, I don’t really give a fuck about my books being in Barnes and Noble,” Richard says. “Even within Big Four publishing and all of their smaller sub-labels and imprints, a book is considered a ‘success’ if it sells 4,000-5,000 copies. I’m not gonna say all our books have done that, but some have come close and some have done more than that. So if that’s their level of success, well, I’ve done that out of my dining room.”

So far, the biggest challenges have been distribution and promotion in a saturated marketplace.

“And anybody who starts one of these things has to learn a little more about taxes than they might like,” Eric Raglin jokes.

Raglin is the owner of Cursed Morsels Press, which relocated to the Twin Cities from Lincoln, Nebraska, only a little more than a month ago.

“I love the Twin Cities. Culturally, there’s a lot of exciting stuff up here. And I wanted to live somewhere that wasn’t a red state,” he says.

That makes sense, considering Cursed Morsels was born out of Raglin’s frustration with American politics—particularly the January 6 insurrection.

“I had this idea for an anti-capitalist horror anthology," he says. "Then January 6, when that happened, I thought, ‘We need an anti-fascist horror intelligentsia.'"

Exactly a year later he released the anthology Antifa Splatterpunk.

Since then, Cursed Morsels has published several anthologies. Even though its author wasn’t yet a Twin Cities resident when he wrote it, No Trouble At All, a collection of tales about terrors lurking behind the veil of politeness, exudes the spirit of Minnesota.

It’s a sterling example of what is known as “quiet horror,” a genre that relies on ambience and psychology to evoke unease, standing in contrast to the more graphic and outlandish writing in Antifa Splatterpunk or, for instance, the gleefully phantasmagoric work like Weirdpunk’s recent hit Chaindevils by Matthew Mitchell.

C.M. Muller, the owner of Chthonic Press in St. Paul, favors quiet horror. Muller is without a doubt the longest-tenured of the Twin Cities small-press horror mavens. He got his start way back in 1989 when, as a high schooler, he took a part-time gig at commercial printer Minuteman Press. Muller and his brother, Brian, used his access to equipment and knowledge of printing to put together a zine about freestyle biking, Motivate Magazine. (“It was like the City Pages of freestyling,” he says.)

That led to him create his first horror anthology, Nightscript, while finishing up high school, and Muller would publish a new volume of Nightscript every October for nearly a decade. After that series ended, he still had an itch to publish new work. Thus began Chthonic Quarterly, publishing collections of new horror fiction four times a year, often featuring rising new writers.

In 2019, he started publishing themed anthologies, the first of which was Twice-Told: A Collection of Doubles, with 22 doppelgänger-themed stories. The fifth installment, Harvest the Night: An Anthology of Folk Horror, is scheduled for October 2025.

Muller has seen a great many changes in the publishing biz since his early days, when email story submissions and websites weren’t yet the norm. Back then, writers still had to print out and mail submissions in a manila envelope, along with a self-addressed stamped envelope for the rejection/acceptance letter.

New technologies have created new avenues for publishing. Jon Grilz went to college with an eye toward print publishing, but frustrations with the sluggishness of the process led him to create Creepy, a podcast featuring audio fiction in the creepypasta vein.

Grilz’s process is significantly different from that of his print counterparts. He has a coordinator who sorts through the many submissions; the top picks go out to his team of professional narrators to record before adding music and production effects.

“We produce at least eight stories a week between our free episodes and Patreon, and still keep a backlog of around 60-70 waiting to be produced,” he says. “In October alone we do about 80 stories since we do two every day for the 31 Days of Horror.”

There’s a kind of democratization to the podcast distribution model, although the sheer abundance of options presents many of the same challenges faced by the ink-and-paper publishers.

“Pre-2020, there were one million podcasts available on iTunes/Spotify,” he says. “Now? Over five million.”

Still, like any good monster, fans remain hungry.

“I keep waiting for [the horror market] to implode, like in the ’80s,” he says, “but it doesn’t seem to be happening. There’s always someone out there bringing something fresh. It’s a good time to be into weird fiction.”

The Twin Cities provide plenty of opportunity for community and promotion for horror fans and creators, Richard says, noting that events like this month’s small-press horror exhibition at Odd Mart’s Odd Market and broader literary gatherings like the Twin Cities Book Festival help spread the horror to local readers.

“The Fright Night Markets at Falling Knife, the events at Utepils … those are some of my favorites,” Muller says. “It’s become a priority to do these local events. There’s an entire ecosystem here.”

So if the Twin Cities are quietly—or maybe not so quietly—becoming a hub for cutting-edge horror fiction, what is so scary about Minnesota?

“Besides our inability to zipper merge in traffic?” Grilz asks.