“Judges Consider Martial Law Case” declared the top headline of the Minneapolis Tribune on August 10, 1934, reflecting how tumultuous a summer the city had been enduring. A brutal police response to a general strike culminated on July 20 in “Bloody Friday,” when police opened fire on picketing truckers, killing two and injuring 67. The following week, Gov. Floyd B. Olson called in 4,000 National Guard troops to lock down the city, and infuriated business owners challenged him in court.

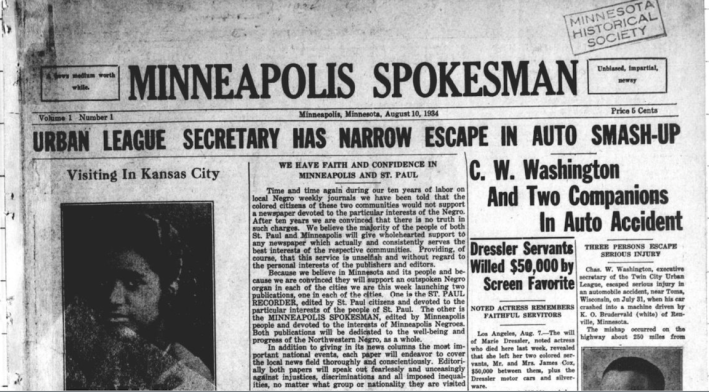

But there was no mention of martial law or labor unrest or the governor of Minnesota in the Minneapolis Spokesman or the St. Paul Recorder that same day. When the first editions of these twin papers hit the streets, readers learned of an event that might hit closer to home: “Urban League Secretary Has Narrow Escape in Auto Smash-Up.”

On that same page, an editorial from the papers’ founder, Cecil E. Newman declares “We Have Faith and Confidence in St. Paul and Minneapolis” and lays out a vision for the papers, promising “to speak out fearlessly and unceasingly against injustice, discrimination and all imposed inequalities” and “aid the worth while institutions of each city.” The issue, which ran six pages in full, cost five cents; an annual subscription cost $2 while, Newman noted, “three months of interesting reading may be had for 75 cents.”

Inside is a “Woman’s World” page edited by Nellie Dodson, who’d also cover sports for the paper. Another page is headed ATTEND SOME CHURCH ON SUNDAY, with services for Black churches listed below. One foreshortened column is filled out with a “Weekly Bible Gem.” News and editorial are hardly kept apart: a squib about two Black men in “a certain unregenerated section of these United States” who lynched a third Black man asked, “More like the white man every day?” “It’s dangerous to call another man’s lady friend a dummy,” began another news brief.

This month, the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder (as the publication became known in 2000 after consolidating its Minneapolis and St. Paul papers) celebrates 90 years in print with its first ever gala and a boat cruise on the St. Croix. It’s not just the oldest continually operating Black newspaper in the state but the oldest Black-owned business.

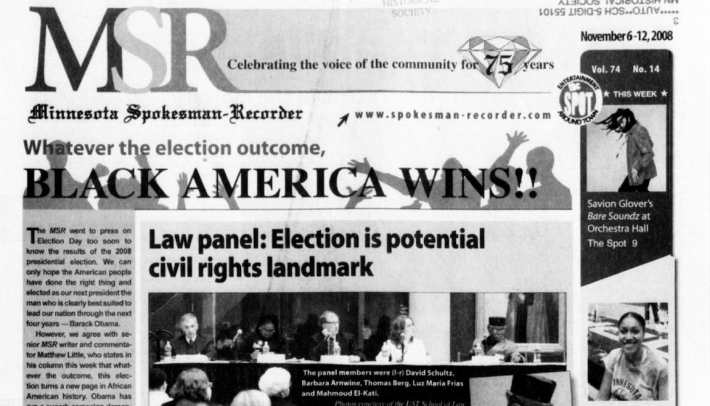

In that near-century, the Spokesman-Recorder has covered national and international stories that directly affected the Twin Cities Black community: a world war, the Brown v. Board of Education decision, the Martin Luther King Jr. assassination, the election of Barack Obama. The paper cultivated talent like Gordon Parks, who worked there as a staff photographer, and Carl Rowan, who proceeded to report on civil rights for the Minneapolis Tribune before landing his nationally syndicated column at the Chicago Sun-Times. And some of the local issues it addressed were themselves of national import—the newspaper is housed just a few blocks down 38th Street from George Floyd Square.

Like all newspapers (and particularly Black-owned papers) the Spokesman-Recorder has faced challenges along the way. Yet at a time when Minnesota lost more than a third of its papers, the Spokesman is still plugging along with a subscription base of 10,000 and about 100,000 unique monthly visitors.

And Tracey Williams-Dillard, Cecil Newman’s granddaughter, has ambitions for the paper she became the owner of in 2007. “How do we really reach broader Minnesota and how can we tell stories that impact African Americans globally?” she asks hypothetically. “How do we make it so we become the national model for people to look at when they're talking about Black stories and really impactful stories that are reaching the Black people globally?”

If times are tough for news outlets now, 1934 was hardly a propitious moment to start any business, let alone a newspaper. Still, Cecil Newman, who’d left the hardline segregation of Kansas City, Missouri behind for the more soft-spoken racism of Minnesota, decided to have a go at it. Newman knew what he was getting into: He’d been editor of Twin City Herald, written for Black papers as prominent as the Chicago Defender, and handled editorial duties for a St. Louis publication. And as a Pullman porter, a relatively prestigious and well-compensated job for a Black man at that time, he had an alternate income stream.

Within a decade, the Spokesman and Recorder had 7,000 subscribers, an impressive number when you consider that the Black population of the Twin Cities then was around 15,000. But Newman sought out white subscribers and advertisers as well, both to bolster his bottom line and, he said, to educate white readers. As he told his biographer in 1969, “The average white inhabitant of Minneapolis or St. Paul knew little about the Blacks of those cities.”

In his newfound role as publisher and editor, Newman became a dynamic voice for integration in the city. He made his name as a community leader when he secured Black jobs at a munitions plant in New Brighton during the second world war. And in the 1940s he aligned himself with the young Hubert H. Humphrey; the two remained close as Humphrey rose from mayor to senator to vice president. When it seemed that Humphrey might be headed to the presidency in 1968, Newman was among three Black community leaders that Jet magazine floated as possible federal appointees.

Newman beat the drum constantly for businesses to hire more Black workers, and the Spokesman also railed against segregated U of M housing in the ’60s. He took on national issues as well, writing, “If Cassius Clay had been a Mormon, he would not have been prosecuted, let alone convicted under the draft law,” when the man who was to become Muhammad Ali refused the draft.

But Newman was no radical. He not only shared Humphrey’s views on civil rights, but also his anti-Communism. School desegregation, in his view, was not only just and right but "would offset Russian propaganda." After the King assassination, he responded to looting in Minneapolis and other cities with vehement retorts to Black Power advocates. “The twisted mind of the white criminal who murdered Dr. King is matched by the psychotic reaction of Stokely Carmichael,“ he wrote. Newman called student protests in the ’60s “the most appalling nonsense that mankind has heard since the Hitler-Stalin days.”

Newman married Launa Jackman, his third wife, in 1967. Unlike her two predecessors, Mrs. Newman, as she was invariably known around the office, took an interest in the newspaper and effectively became Newman’s partner. She’d moved up from Des Moines less than a decade earlier with her two children, Norma and Wallace (better known as Jack) and established herself as a formidable presence.

“My grandmother was a tough cookie to work under,” recalls Williams-Dillard. “She'd chew you out in a heartbeat. If you did something wrong, you heard about it—or if you didn't do something wrong, and she was just in one of the moods, you'd hear about it.”

Charles Hallman began working at the Spokesman in 1990, and his byline has appeared in every issue since. “Jack Jackman interviewed me and hired me, and Mrs. Newman was a little perturbed by that. She thought that he should have consulted with her first,” he says with a chuckle.

“At her funeral, Jack told me she really respected me because I stood up to her,” Hallman says. “A lot of people were kinda scared of Mrs. Newman. She was a lovely lady, but there were some times she and I would have a little discussion, and I wouldn’t back down.”

Though best known as a sportswriter (and an early champion of women’s basketball), Hallman went where he was needed over the years, as happens with a small newspaper. That’s how he wound up writing editorials, including one that targeted a TCF executive for certain improprieties. “I didn’t know that he had loaned money to the paper,” Hallman says.

But Mrs. Newman knew. “She was really mad, to the point where I thought she was gonna let me go,” Hallman recalls. But for all that, she did not step in. “The editorial ran as is. She kept it in the paper.”

To peer back through the Spokesman-Recorder archives is to read the history of the Twin Cities from a different vantage point than white mainstream sources offer. A story may be recognizable, but it doesn’t always have the same moral.

In the early 2000s, the paper homed in on the Hollman Consent Decree, a judicial agreement that was to end segregated public housing in near north Minneapolis. While this might seem like a straightforward good from the outside, there were concerns (justifiable, as it turned out), that this was an excuse for developers to reclaim and gentrify a chunk of profitable real estate once they leveled the Glenwood/Lyndale homes. Community editor Jerry Freeman called out City Council President Jackie Cherryholmes and even Mayor Sharon Sayles Belton, whom the paper had celebrated for leading a “charge of African Americans into office” eight years earlier when she became the first Black mayor of Minneapolis.

“They essentially tore our ghetto down and built up all the new housing units there, and they were trying not to give the African-Americans they uprooted the opportunity to come back,” says Williams-Dillard. “And so we were really on that story until they had to make a certain amount of housing available for at least some of that community to return.”

Charles Hallman was responsible for a three-part series on racism at the Minneapolis Parks Board, and when a tornado ripped apart north Minneapolis in 2011, he looked closely into whether relief efforts were reaching the right people.

But reporting the news was never the Spokesman-Recorder’s sole purpose. The paper’s perspective showed through in their entertainment coverage as well. A 1984 review of the movie Purple Rain plays up the images of “Black folks having fun,” going on to say, “Black streets, warehouses, railroad tracks, polluted river banks, First Avenue, are suffused with light and song. Prince, our hometown genius, transforms his own inner city into shared life and lived music.” When Prince died in 2016, poet and playwright Stephani Maari Booker wrote about how the alternative to hypermasculine Blackness that Prince offered meant so much to her as a Black queer teen in the ’80s.

The Spokesman-Recorder also became known for the strength and consistency of its sportswriting. Hallman and his colleague Kwame McDonald campaigned successfully to get U of M basketball legend Linda Roberts’s number retired. In 2009, the Spokesman-Recorder’s Larry Fitzgerald Sr., the father of the Holy Angels grad and Cardinals wide receiver, became the first dad to cover his son in the Super Bowl.

And then came the murder of George Floyd.

“The Spokesman-Recorder was instrumental in covering the aftermath of the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd, and bringing forward perspectives that the Black community needed to hear and to know and to understand,” says activist and former Minneapolis NAACP president Nekima Levy Armstrong. “They covered the issues through a racial justice lens. They connected well with activists who were boots on the ground, including myself.”

Mel Reeves, a longtime activist against police violence who was the community editor at the time, wrote in a fiery editorial that no one should have been surprised by the riots in the streets. (Reeves died in early 2022 of Covid.) “A beaten down people will not stay beaten down forever,” Reeves wrote, adding this demand: “JAIL THE KILLER COPS NOW!”

“George Floyd, yeah, we got a lot of recognition from that,” says Jack Jackman, with some perspective. “And all the signs popped up: Black Lives Matter. Racists decided, yeah, they're right. Maybe Black people do matter. And so they started putting money into the Spokesman, which works out real well.”

After 90 years, so many of the voices that belong in this piece are gone. Cecil Newman himself died in 1976; Launa Newman died in 2009. And earlier this year, Launa’s daughter (and Tracey Dillard-Williams’s mother) Norma Jean Williams died as well. A comedian and a raconteur, “she left a big social footprint,” her niece Dauhn Jackman recalled in a Spokesman-Recorder tribute.

But her brother and co-publisher for most of the ’90s, Wallace “Jack” Jackman, is still kicking around.

Full disclosure: I have a tiny part to play in the history of this newspaper, a paper that played a major role in my professional life. In 1997, when I first moved to Minneapolis, Jack hired me for one of his many side ventures: a newspaper for teens called YouthSpeak. He drove me down to Mason City to buy a car from his cousin, and taught me how to drive stick shift on the way back. YouthSpeak lasted about six months, but it was my first journalism job, and when it folded, Jack hired me to work at the Spokesman.

Jackman himself drove trucks, first as delivery man before moving on to long-hauls, and didn’t have much to do with the paper when he was young. “But my mother was getting older, and I wanted to go in there and help her, to learn about the business,” he says. “I’d get off work and go to the Spokesman. I looked around and figured out what was going on. I'm not a writer, by any means. So I went in and figured out what I needed to do,”

Jackman modernized the organization, bringing in new equipment and cutting costs. He replaced the old lettertype press, which required two trained workers, with a topographic press that he hired his wife Lynda to operate. Computer systems soon followed as the newspaper raced to keep up with technology.

At the time I was there, the Spokesman was a rough and tumble operation. Cigarette smoke clogged the air as community members bustled in and of the building, some partners in one of Jack’s many side hustles. He distributed Pride brand pop and potato chips, which contained an African history fact on the bottle or bag, though he seemed to give as many away to neighborhood kids as he sold in stores. He published a directory of Black businesses called the Minnesota Black Pages.

Today, the Spokesman-Recorder offices are quieter and the air more breathable. Even the exterior has a fresh look: a mural facing 38th St. with the faces of the paper’s many notables. The day I visit, current editor Al Brown is typing quietly away, and though Williams-Dillard jokes about the noise sales manager Ray Seville is making, the office is like a library compared to the Spokesman of old. Williams-Dillard leads me to a room, once part of a sprawling warehouse, that’s now an up-to-date studio for a video podcast.

Williams got her start at the Spokesman at eight years old. “My grandmother brought me in, and she was like, ‘OK, we're gonna find something you can do,’” she says. “And I was a quick learner, so I was taught how to run the Addressograph machine.”

When she got older Williams-Dillard drove the paper to Shakopee to be printed, learned billing, and became “self-appointed” office manager. “Everybody kind of had given me that respect because I was the owner's granddaughter,” she says. “My grandmother didn’t scare me so I used to go to a lot of events with her and meet some of the people I still talk to today.” Williams later became sales manager, again self-appointed—clients didn’t need to know she was the paper’s only sales person.

After her mother and uncle stepped down, a little over a decade ago, Williams-Dillard took the reins. While onetime giants of Black publishing like the Chicago Defender were sold to newspaper groups, the Spokesman-Recorder has remained a family venture. Williams-Dillard plans to hand the paper over to her daughter, Leticia Alvarez, who is currently working on an archive project for the upcoming celebration.

“So she's found herself in the archives.” says Williams-Dillard. “She's been in the paper several times. I had a birthday party once, and I put her whole party in the paper. It's a community paper, right?” she says. “You share your family's lives, hoping other people will see what you're doing and want to do the same thing. So we offer the opportunity for people to publish their weddings in our paper.”

That emphasis on community plays out in how the Spokesman-Recorder covers events. “Take Rondo Days,” she says. “You have the Star Tribune saying there were some gunshots, or whatever. Our viewpoint is that it was well attended, and for the most part, everybody had a great time, because that's the story we want people to know about. If there was one incident, even if nobody got hurt, the start of the Star Tribune's making sure you knew about that one incident put a negative spin on it. Well, we're always talking about how positive our community is, so we're giving it a whole different look.”

And yet, the definition of community has changed with the years. “It’s not like it was when my grandfather started it,” says Williams-Dillard. “Our community is as big as where African Americans live, so Detroit could be a part of our community. It could be the Minnesota community. It could be a national community, as long as the stories we tell are relevant.”

And yet, there’s something to what Williams-Dillard says that does remind me of her grandfather’s vision, in which community journalism connects people to the world outside their neighborhoods by reminding them who they are. “Publishing the news about our Negro community raised our morale,” Cecil Newman said back in 1969. “It made us feel that we were really part of the big city.”