Racket collaborated with the Bethel University Arts + Culture Reporting class to produce the stories you'll read this week. Our editors worked with students, mostly juniors and seniors, to develop ideas, source stories, and edit them for the enjoyment of readers. Feel free to seek out these young journalists, photojournalists, and graphic designers to fill your internships and jobs. They like to get paid for their work, and thanks to Racket members and a grant from Bethel, they got cashed out for these pieces. Enjoy!

Professor Erica Stonestreet is teaching her kids ethical ways to say “fuck,” a word she says has seen an uptick in her vocabulary since St. Ben’s lost multiple philosophy faculty and nearly put an end to her department’s major. In the provisional office she shares with a mathematician in a building on the far edge of the St. Joseph campus, light filters through the boughs of leaves obstructing the window’s southward view. Stonestreet sits, a cup of coffee between her hands.

“One of my colleagues used to say that answering the questions of life is inevitable,” says Stonestreet, who’s chair of the philosophy department. “The question is if you do them with intention or not.”

How valuable is the discipline of philosophy to today’s students? The university’s answer was loud and clear: In a 2021 academic prioritization process led by the provost, the College of St. Ben’s and St. John’s University proposed cutting the major entirely. The looming demographic cliff, which could result in a dramatic drop in enrolled college students across the country, forced CSBSJU to financially reshuffle to adapt to the anticipated blow. The provost came to the conclusion that, along with every language department except Spanish, the philosophy major wasn’t worth it. However, this was not the end of the story.

“Ours was the only program that survived the process,” Stonestreet says. “We did save the major, but I’m pretty sure it was the monasteries that argued, ‘We’re a Catholic institution, you cannot cut philosophy.’”

Though Stonestreet herself isn’t Catholic, or religious at all, she appreciates the monasteries for their “steel backbones,” keeping alive the discipline she fell in love with in undergrad after reading Plato’s Apology for the first time.

Her love for philosophical wisdom isn’t isolated to the ancient Greeks or 20th-century analytic linguistics—philosophy influences the way she looks at everything. Just look at her Substack, Humaning is Hard, but Philosophy Can Help, which she writes on her own time for people who may not have the means or time to study philosophy at a private liberal arts school. Who knew there was a philosophy of dessert?

Philosophers get a bad rap for staying perched in the ivory towers of academia, rarely venturing out into the real world. As a philosophy major myself, I can’t count the number of times I’ve gotten a snide remark from a STEM major, survived a boomer joke about burger flipping, or read something saying my degree is useless. So I decided to seek out three professional philosophers from Minnesota and see what they were doing in the world. Spoiler: They aren’t just using big words to sound smarter than you.

Everywhere, Except the Conferences

“Philosophy is everywhere,” Stonestreet says. “My kids roll their eyes and groan when I say those kinds of things, but it’s true.”

Even if her own university needs monks to advocate on behalf of philosophy, she’s determined to give others the tools to become better people and more thoughtful citizens. And she does so in a way that makes sense, so you don’t have to trudge through the wordy bogs of Hegel or Schopenhauer to feel philosophically fulfilled.

Plus, she says, academic philosophy has become an entirely different animal than what philosophy actually is and always has been.

Philosophy helps us define our values—for example, a little philosophical analysis tells us that American capitalism works because our cultural ethos tells us that people are isolated individuals and, thus, the pursuit of self-interest is intrinsically good. If we believe something else about human nature, like that we all by nature depend upon each other, or that care is more valuable than capital, we achieve a different economic system. At this point, capitalism is the force that’s dictating what critical thought is worth, rather than the other way around.

“Ideally, I would love it if we could get back to a relational mindset, [understanding] that we are all interconnected and that we need to start seeing each other right,” she says, sighing. “We would probably have a lot more support for families, and carers and people would get medical coverage.”

Stonestreet steps aside to take a call from her daughter, who suffers from a long-term illness. Stonestreet writes in her blog about what it means to balance pain and happiness in the everyday. She knows that happiness is more than just emotional wellbeing and peace, and being a mother is so much more than just being a caretaker.

Stonestreet skipped the second day of last year’s American Philosophical Association conference to explore the New Orleans garden district with her partner. She says she can’t stand the “stupid minutiae” that professional philosophers talk about in lecture halls, disconnected from everyday human realities.

“The joke about the PhD is that you know more and more about less and less until you know everything about nothing,” she says. “And philosophy can be that, but we [must] pull it back and think about why these ideas are actually relevant.”

Stonestreet leans back in her chair, visually exhausted from trying to show her university and the world that understanding the human story is not a worthless endeavor just because the market happens to suggest so.

“Ideas do things in the world; philosophy matters, because what you think about what humans are is the root of everything else that grows out of it,” she says. “These ideas do have repercussions—and real ones—in the real world. That’s part of why I started the blog.”

Philosophers Anonymous

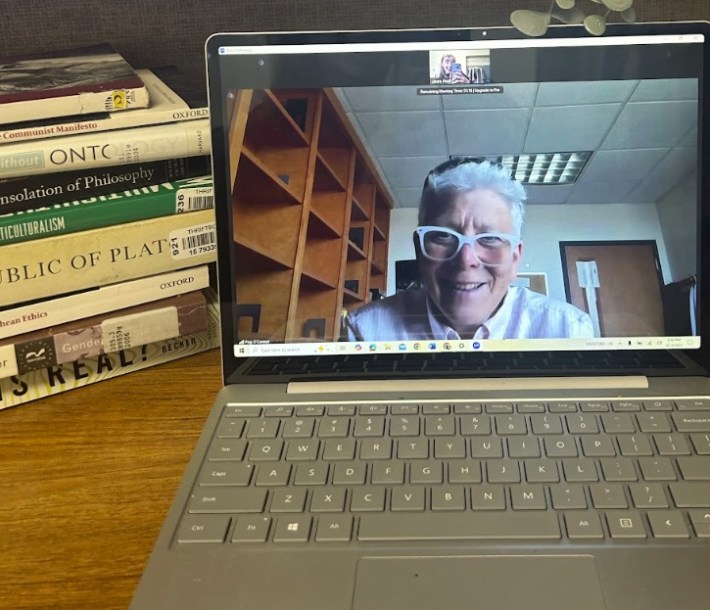

Professor Peg O’Connor loves 20th century Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, and she’s a recovering alcoholic. While she initially fell in love with philosophies about systematic power and oppression, now her passion is using intellectual tools to rethink trauma and addiction. She accomplishes that by posting videos about philosophical reflections on sobriety, trauma, and living a good life as @thesoberphilosopher.

“Philosophy helped me get and stay sober,” says O’Connor, who teaches feminist ethics at Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter. “[I used to] get my philosophical work and my identity as an alcoholic completely segregated for no good reason… and then I had this kind of epiphany like, ‘Oh my god, I’m just the biggest goober in the world.’ Because I have found people struggling with addiction to be some of the most philosophical people in the world.”

O’Connor found herself and others in recovery asking questions like, “Am I the same person I am now when I was back drinking?” and, “How do my repeated habits make me who I am?” Aristotle talked about this stuff for centuries, in life and beyond. Because of her formal philosophical training, O’Connor says, “I saw myself as having [an] incredible treasure trove of concepts.”

And O’Connor didn’t want to keep that treasure trove reserved for people who can pay $30,000 a year for philosophy degrees at Gustavus. So, in addition to the TikToks, she’s also written a book and workbook about the places where philosophy and recovery collide, influenced mostly by the 20th century philosopher William James, who was a primary influence on one of the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous. “It’s been a real joy making philosophy available to people, because it is so powerful, it is so helpful, and it can be so transformative,” O’Connor says.

Like Stonestreet, O’Connor views philosophy as, unfortunately, an elitist and private pursuit these days, when historically it was intended to be for everyone. The point of studying philosophy has never been for a select few PhDs to argue with each other about speculative epistemology.

“Philosophy, in many ways, has become an overly narrow, specialized discipline that has lost its way on some accounts,” Stonestreet explains. “Because if you think about Socrates, he was out in the streets philosophizing. If you look at the Epicureans, if you look at the Stoics, they were always engaged and busy and doing things.”

Aristotle Organizes Art in the Park

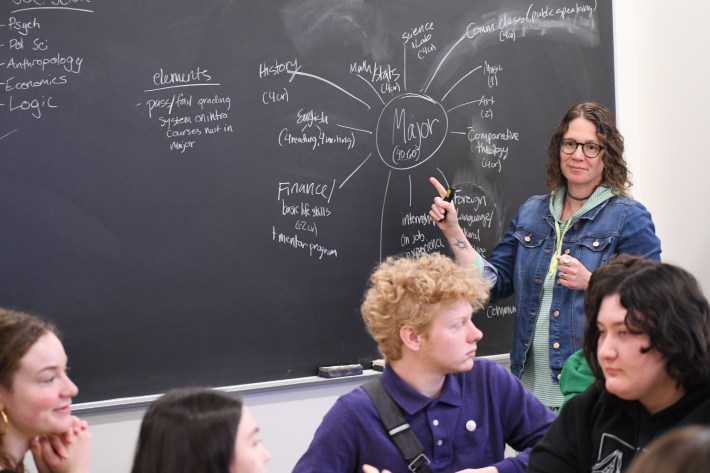

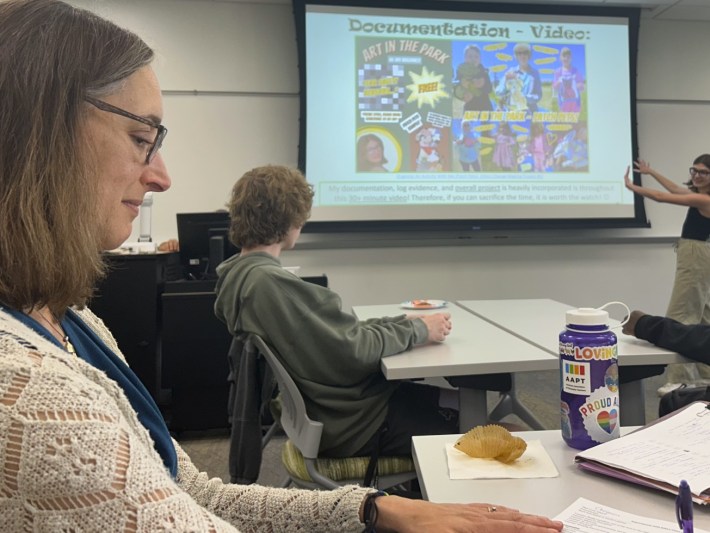

It’s presentation day in professor Mo Janzen’s ethics class at Anoka-Ramsey Community College. She brings homemade chocolate-chip muffins to share with the group, insisting that everyone take one (this reporter obliged; they were delicious). She invites presenters to stay in their seats as they talk through their slides if they’d prefer, accommodating those who may be too anxious to stand up in front of the group.

A student whispers to Janzen across the table, “Mo, am I going to lose points for not adding a title to my presentation?”

She shakes her head and smiles warmly. “Not at all. You know, life is just so short.”

The presentations are on what Janzen calls “experiments in ethics,” a project worth 40% of each student’s final grade. The whole process spans around two months, and involves: identifying ethical issues in local communities; reflecting on how students can contribute their life to helping out by following an Aristotelian model of virtue cultivation; volunteering at least four hours in the community; and finally, organizing an activity, either with a group, or on their own.

The activity comes with a list of objectives for the project. The one at the top of the list? “Make a difference.”

One student’s project involved assembling care kits for homeless people, and passing them out to the class so that every student could keep one in their car in case they encountered someone in need.

Another student organized a free art activity for kids in a public park, and made a full-length video to inspire others to do so, too.

A third group spent their 10 weeks coming up with the idea to make 13 peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for their baseball team on the day of a double header.

“I always tell my students I was seduced by philosophy. My first philosophy class was like, unlocking a door.” Janzen says. “I realized I was part of this conversation that had existed through time. These were questions everyone was asking about, like, how to live a good life. Like what do I owe to other people? How do I contribute to society as a good citizen?”

And these questions aren’t secondary to the work that Janzen does. They are the reason why she chooses to invest her heart and time into the wide diversity of students that take her classes. Located in Coon Rapids, Anoka-Ramsey is an open access community college, allowing many people from differing backgrounds and walks of life to take classes regardless of past academic performance or ACT scores.

Janzen used to teach at St. Catherine’s University and University of St. Thomas, and says even though the reputation of a community college might not compete with a four-year, expensive, private institution, she’s still “offering a high-quality class that’s very similar to [a private school].”

The change in demographics doesn’t mean philosophy is any less important or useful for any of her students.

“You have people with a wide variety of backstories,” Janzen says. “Some of my students have traumatic backgrounds. Their parents might have addiction issues. They might have big responsibilities taking care of their younger siblings or helping to support their families and that… We just have a lot of slices of the social pie.”

But Janzen knows that philosophy shouldn’t be reserved for people who can pursue an elite degree. Anyone living an examined life should have the opportunity to think critically about why they’re living and what it means.

While Janzen was in grad school at the University of Minnesota, she worked with a classmate to develop Engaged Philosophy, a program that aims to get students out of the classroom and into their communities, doing ethics in real life, the way the ancients intended.

“We loved philosophy,” Janzen says of her old classmate, Ramona Ilea, who now teaches at Pacific University in Oregon. “But we struggled with just studying it in an academic way, because both of us really felt like it was about living a good life,” Janzen says.

Years later, Janzen has overseen hundreds of student projects spreading peanut butter and talking Plato. And most of all, she sees that her students make a difference in the world and their communities through the way that they think and, in turn, act.

“Our class is about saying, your small actions matter in the world, and the little things that you do are part of living a good life,” Janzen says. “Certainly, living an ethical life.”

Laura Hunt is a senior English and philosophy major at Bethel University. She loves bluegrass fiddle, hiking around the North Shore, and talking about deep stuff around campfires with anyone who will have her. She’s hoping to pursue a law degree in the fall of 2026.