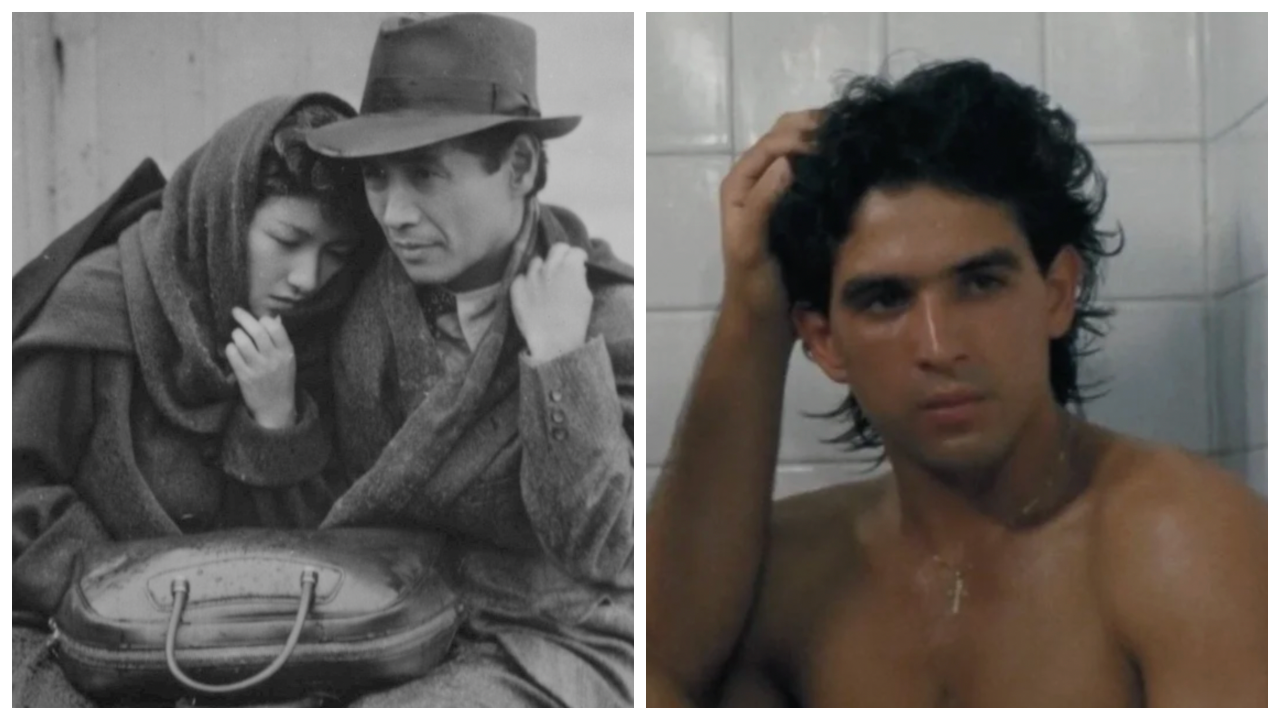

Detective Jessica Miller spends hours studying the black-and-white photographs. Three little boys peer back at her from the grainy images, and she sometimes feels like she can hear them pleading. When she listens to recorded interviews from the 1990s, the intonations of each voice burrow into her memory. When she closes her eyes, she sees the boys’ faces staring back at her. When she tries to sleep, those audio clips play on a loop in her mind.

“I can’t let this case go. I can’t seem to walk away from it,” Miller says. “Something happened to those boys, and I owe it to the family to figure it out.”

The mystery this detective can’t let go of is Minnesota’s oldest missing persons case on record: The disappearance of three brothers, ages 8, 6, and 4, who were last seen in north Minneapolis on November 10, 1951. The Minneapolis Police Department found two of the boys' winter hats atop the frozen Mississippi River, and assumed they had drowned. They closed the case after five days of searching. While many assume they’re dead, the Klein brothers—Kenneth Jr., David, and Daniel—are still officially considered missing.

There are those, like Miller, who won’t let the cold case slip away. The Wright County detective is just the latest in a decades-long lineage of sleuths—family, law enforcement, journalists—who’ve become captivated by the vanished Klein brothers. They believe people are out there with knowledge about what really happened on that frigid day 74 years ago. The disappearance has spawned several unproven theories—that the Minneapolis Police Department was complicit in an abduction, that the boys’ remains are entombed under a neighbor’s basement slab floor. “Nobody knows what happened to these boys,” Miller says.

In recent years, Miller and the Klein family have worked to reopen the case in Minneapolis. They’re determined as ever to solve it.

“Where are they? Will the family ever know what happened to their three boys?” the detective asks. “They wanted answers and had to live their whole life without having any.”

A Park, A River, Three Missing Brothers

In the early 1950s, Minneapolis was a booming city. The population had swelled to its highest-ever mark of around 520,000, the downtown area never felt more alive, and residents were energized by America's surging post-war economy and sense of endless possibility.

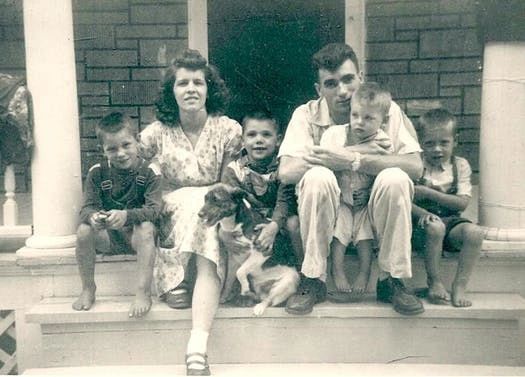

The Klein family was just as optimistic. Betty Klein was pregnant with her fifth son, and the family was looking forward to adding more to their clan.

On November 10, 1951, Kenneth Jr., David, and Daniel wanted to go play at Farview Park, a grassy 21-acre hilltop park known for its views of downtown Minneapolis. Farview was only a couple of blocks away from the Klein home at 2931 Colfax St. N., and the kids would often venture there on their own. Nothing seemed out of the ordinary. Gordy, the eldest Klein brother, was supposed to go with them that day. Instead, he stayed home, telling his mother he felt ill, according to the original police file. The three boys left for the park around 1:30 p.m., and Gordy went to retrieve them around 4:30. When Gordy arrived at Farview, his brothers were nowhere to be seen.

The Kleins called the Minneapolis Police Department a little after 8 p.m., according to the file. MPD informed the Kleins they would look around Farview Park and would check in with them later. Police called at 3 a.m. on Nov. 11 to see if the boys had returned home. MPD wouldn’t send detectives to the Klein residence until 6:30 p.m. that day, almost 24 hours after the boys were reported missing. A door-to-door search was conducted, and additional teams were brought in. A dog tracker led police to the Mississippi River—about a half mile east of the park.

Detectives came up unsuccessful. On November 12, the Kleins filed a missing persons report. The next day, a railroad worker found two of the boys’ hats a couple miles downstream from where they were last seen near the Mississippi.

Police lowered water levels along the river, from Lowry Avenue to the St. Anthony Falls Dam, in hopes of finding more evidence of the missing boys. They found nothing. No new clothing items. No bodies. No clues to shed light on what happened to the brothers. Two days later, on November 15, MPD would rule the Klein brothers' deaths as accidental drownings, but their parents never believed it. Kenneth Sr. and Betty didn’t think their boys would wander off on their own.

In the early 1950s, mafia-related crimes, such as gambling and complicated financial schemes, topped MPD’s list of priorities. The department’s nearly 600 sworn officers had not dealt with a missing persons case of this magnitude before, according to Minnesota historical records. Video cameras weren’t widely used, cellular data didn’t exist for tracking purposes, and the advent of DNA forensics was 40 years away. Detectives had little to go on.

The Lifelong Hunt for Answers

“Have You Seen These Boys?” reads a newspaper ad from 1951. “Boys Father Sets Reward” reads another from the following year.

Betty and Kenneth Sr. ran ads every year in the Minneapolis Star on the anniversary of the disappearance, pleading for the boys to come home or for anyone with information to reach out. Over different points in their lives, brothers Donald, Mike, and Tom Klein have joined the hunt, refusing to give up searching for the siblings they never met. (In total, Betty had eight boys.) The Kleins said they remember family vacations stopping after 1951; their parents spent every disposable dollar on traveling around the country, chasing any and all tips on the whereabouts of their boys.

When the kids went along with their parents to search, Betty would always buy trinkets for each of them. At home, Kenneth Sr. taught his boys how to fix cars and tie a tie. Mike, Tom, and Donald beam with pride when talking about their loving parents, but the Klein kids always felt unnerved about what happened that day at the park.

“My family has ghosts around them,” Tom says. “They never discussed a lot about the boys, but we knew.”

The Kleins would grant interviews to the Star Tribune and Monticello Times for the next three decades, hoping to keep the story alive so that someone with information might come forward. “I’d like to make a plea to all you people to help us find our boys,” Betty says in a radio interview from 1955.

For the 40th anniversary of the disappearance, the Kleins wrote to the makers of the long-running network TV series Unsolved Mysteries, but the show’s producers declined to make an episode about the missing Minnesota brothers. More interviews with local media outlets would come in the wake of the 45th anniversary, where the family showed age-progression photos for two of the boys, excluding Danny, who was considered too young for the technology to yield helpful results.

Frustrated with the lack of evidence MPD had uncovered over the decades, the Kleins decided to hire a private investigator, Mike Sadovich, in 2004. Sadovich worked on the case for two years without turning up much of anything.

Betty refused to accept that her boys were dead. She kept every letter, every photo, and every person’s contact information she received. Donald is now in possession of those items, living in the Monticello home where Betty died in 2013. Kenneth Sr. died eight years earlier.

Every time the Kleins went to MPD for help, they were repeatedly told to move on with their lives. The case was closed, and, to MPD, had been solved since way back in 1951—there was nothing more they could do.

A New Hope

Fifty years after Kenneth Jr., David, and Daniel went missing, a Minneapolis cop resparked momentum around the cold case. In 1998, Sgt. Jim Schultz began examining all of the evidence, interviewing each member of the Klein family, and reaching out to fellow officers who once worked the case. Nobody within MPD had explored the disappearance of the brothers in earnest since 1951, and Schultz quickly began making real progress.

One of the major breaks? The emergence of a potential suspect. The man, a neighbor, poured concrete in his basement and replaced his wooden truck bed the day after the boys went missing. The busy neighbor reportedly told authorities that, “The boys weren’t worth looking for.” Frustratingly, Schultz discovered the man had died in the late 1970s, and none of his family could be tracked down.

Jack El-Hai got involved around the same time as Schultz. The freelance reporter and author wrote an article in 1998 for Minnesota Monthly, headlined “The Lost Brothers.”

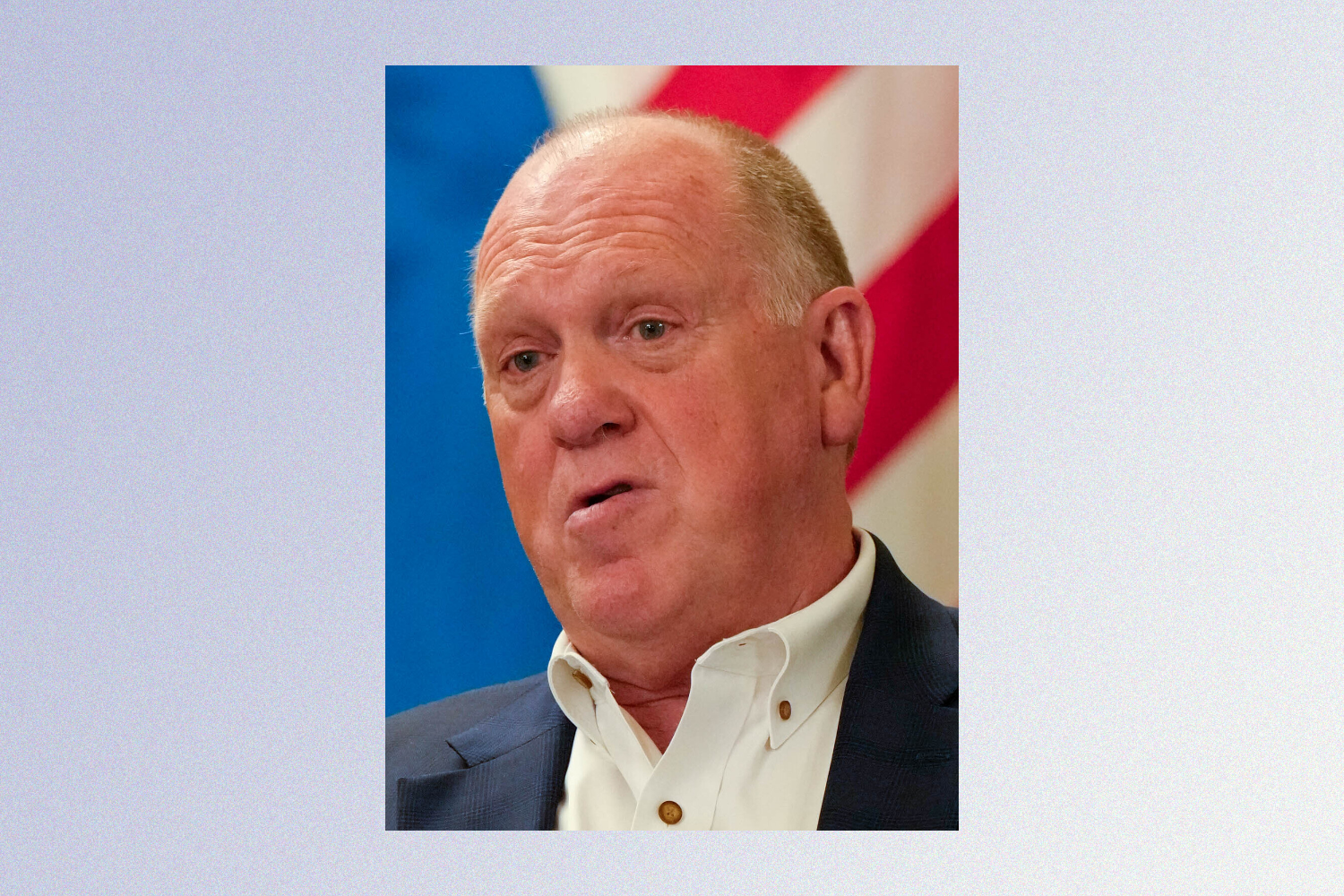

Schultz and El-Hai reinvigorated public attention around the Klein brothers’ disappearance, but they couldn’t deliver conclusive answers. It would be over a decade before another detective got involved—Wright County Sheriff's Deputy Jessica Miller.

Detective Miller and her partner, Lance Salls, started looking into the case in 2010. That same year, she learned the bones of a child were discovered in Otsego, Minnesota. She wondered if this could be the missing piece to a puzzle others spent decades trying to solve. DNA evidence, however, confirmed the remains didn’t match the missing boys—yet another dead end.

Miller and Salls would work the case for six years before presenting their findings to the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. In 2016, they finally succeeded: Thanks to persistence of Miller and Salls, the BCA ordered the 65-year-old Klein cold case to be reopened within the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

“No One Was Willing to Help Them”

Mike, Tom, and Donald all expressed distrust with MPD throughout the investigation. They say their family has been mistreated, and that the department has refused to help them find closure.

“As far as general law enforcement goes, as far as I’m concerned, all they did was [make] sure we couldn’t pursue the case,” Donald says. MPD officers have been reluctant to help, Tom believes, because they fear the “black mark they would have against them” if the truth ever came out. In the 1950s, the department was notorious for corruption, and Tom thinks the police played a role in covering up what happened to his brothers.

“I believe the police department failed all the way,” Tom says. “I believe they were kidnapped by the police.”

But it was Betty who harbored the most mistrust in how MPD approached her children’s case. Schultz, the P.I., asked Betty who he should approach about potential sources of evidence during a 1998 interview. “I think the Minneapolis police, but I don’t think you’d get nothing out of them because we went down there and they told us that they destroyed all of that [evidence],” Betty responded.

The next day, Kenneth Sr. told Schultz he believed MPD was involved in the disappearance because officers “acted like they weren’t really interested.” According to Kenneth Sr., cops who were helping the Kleins were allegedly told by their bosses to drop the case or risk being fired.

Detective Miller echoes the family’s frustrations, but says there were parts of MPD’s investigation that were “impressive, especially back then.” She says officers searched extensively for the boys even after closing the case.

El-Hai expanded the scope of his Minnesota Monthly article with a 2019 book about the Klein case. In The Lost Brothers, he combs through the details of the disappearance while detailing MPD’s “inadequate” 1951 investigation.

“[This case] showed me how when the boys disappeared in 1951, the police methods were very criminal,” El-Hai says today. “This investigation was quite inept, but I’m sure it’d be handled differently now, and that’s a big handicap in old cases: They were handled so poorly and so quickly.”

When he first started looking into this case, El-Hai recalls, MPD officials claimed they couldn’t produce any of the original records of the investigation—the department had apparently misplaced them. He was later sent copies of files investigators had given the Klein family back in 1951.

Before MPD reopened the case in 2016, the department denied the Kleins access to the files, according to Donald, who says at one point his family was told the file never existed. Mike says he has viewed the alleged files, but that MPD did not let him read anything inside the folders. The family has requested access to MPD’s file on their lost brothers for years, though they’ve never received access—until Racket obtained a copy for this story and shared it with them.

Sgt. Garrett Parten, a spokesman for MPD, wouldn’t answer questions about the missing Klein boys. Instead, he tells Racket that each precinct has an investigative unit that focuses on missing persons cases, though particularly complex cases might be transferred between bureaus. MPD does not have a dedicated missing persons or cold case unit.

As he interviewed officers over the years, El-Hai became increasingly upset with MPD’s handling of the case. When Betty and Kenneth Sr. would make requests of MPD, he says he watched the department ignore them.

“I feel compassion for the Klein family because they were treated dismissively by the Minneapolis police,” El-Hai says. “No one was willing to help them for a while.”

What Happened to the Klein Brothers?

Mike, Tom, and Donald, now in their late 60s and early 70s, each have different theories about what happened to their older brothers. None of them have been proven.

“They were healthy, they were good-looking kids, they were strong,” Tom says. “They were everything somebody would want in a kid.”

In 1996, a man responded to the Kleins’ newspaper ad claiming he was David Klein. The apparent breakthrough seemed too good to be true, Tom recalls. Despite some hesitation, Mike and his parents traveled to Arizona to meet a man named Tom Kemp. Mike says he knew it was one of his lost brothers because Kemp was able to produce specific details, like playing in the Klein grandparents’ backyard.

But DNA testing proved that Tom Kemp, who died six years ago, was not David Klein. To this day Mike believes Tom Kemp was David, and Betty believed he was, too. But to Tom, it was yet another dead end.

It's estimated that around 2,300 children are missing any given day the U.S. Donald and Tom both have unproven theories about their brothers being sold into labor after being abducted by MPD. Tom believes the brothers were sold to farmers or families who had lost their boys in WWII; he's convinced his brothers were sold into labor, despite the Klein family not being immigrants. (To this day, the U.S. faces a crisis of migrant children being forced to work dangerous and illegal jobs.)

“We have immigrant children disappear without a trace. Nobody wants to talk about it,” Donald says. “It’s just something that’s always been around and will continue to be around.”

Eleven years after the boys went missing, another member of the Klein family was taken. When Donald was five years old, his parents fostered a young boy who they’d hoped to adopt. One summer day, Donald and his foster brother were playing outside when two women pulled up into the Klein’s driveway. One of the women picked up Donald’s foster brother and threw him into their car. Later in life, Donald was told these women worked for Wright County Human Services, and that they’d reportedly sold his foster brother to a woman. (Miller couldn’t find any recorded proof of this, but acknowledged the family’s version of events could be true.) According to family lore, that woman had a judgment against her stating that she was not allowed to have foster children in her care; at the time, her parental rights were in limbo regarding her own biological children. The boy died 18 months after he was taken from the Kleins’ driveway, according to Donald.

Another potential theory? That the boys were murdered. Over the years MPD has named two individuals as suspects, one of whom received considerably more attention from investigators: A nextdoor neighbor of the Klein family who had been accused of molesting another neighbor’s five-year-old daughter. This was never proven.

Donald believes it is highly likely that their neighbor had something to do with his brother’s disappearance. This is the same man Schultz investigated, the one who poured concrete in his basement the day after the boys went missing. Investigators have asked the current residents of that neighbor's house for permission to use a ground-penetrating radar to scan for bones beneath the basement floor. Each time law enforcement has asked, the homeowners at the time have declined.

The other alleged suspect is Richard Fosse, a playground instructor with the Minneapolis Park Board who often worked at Farview Park. Fosse moved out of the area soon after the boys went missing. In 1955, he was named as a potential accessory to the murder of three boys in Chicago. Fosse’s role in the murders was never proven, if he had any role to play at all.

Law enforcement has changed dramatically since 1951 and so has the immediate response to missing children. Back in the ’50s, there was no urgency to find missing people until at least 24 hours later, Miller says. (Patty Wetterling, whose son Jacob was abducted and murdered in 1989, advocated for Minnesota to adopt the Amber Alert system, which eventually launched here in 2002.)

“It really wasn’t viewed as ‘OK, there’s real danger here, and we need to get on this now,’” Miller says.

Detective Brad Volk of Washington County Sheriff’s Department has been working on a missing persons case since 2020. It’s the disappearance of Todd Hanson, a 25-year-old from South St. Paul who went missing in 1993. The friend he was with was discovered dead in the Mississippi River, but Hanson’s body has never been found.

Volk says missing person cases can leave detectives feeling haunted, struggling to provide justice to the ghosts surrounding them. He wanted to solve the Hanson case due to suspicious circumstances surrounding it, but also to provide closure to the family.

“If I don’t solve this case, it will just move to the next desk for the next investigator to try and solve,” Volk says. “I don’t want that to be the case.”

Losing Faith While Holding Onto Hope

Donald Klein walks into the Monticello Perkins wearing a tattered flannel shirt and worn-out blue jeans. His salt ‘n’ pepper ginger hair peeks out from under his faded Hard Mt. Dew hat. His hands are calloused from stocking liquor bottles at Hi-Way Liquor.

His icicle eyes resemble his father’s, and he holds a folder containing all the letters his mother had collected over the years. Those icicles melt away when he speaks about the deaths of his parents.

“I am who I am today because of them,” Donald says. “I think about them everyday, and I miss them everyday.”

Donald says the love between his parents only grew stronger after their three boys disappeared. Instead of letting the tragedy drive them apart, the Kleins knew they were stronger together.

As he explains how losing the kids impacted his parents, tears slowly form puddles next to Donald’s lukewarm cup of black coffee

“They both died without knowing what happened to the boys,” he says. “I pray to god they know what happened now that they’re all together.”

Some, like MPD, would say this case has been solved, and that the Klein brothers drowned in the Mississippi River on November 10, 1951. To others, like the family and Detective Miller, questions linger.

Miller says she doesn’t believe the boys are still alive. Without going into too much detail, she says she thinks there’s someone out there who knows what happened to them.

When asked if he still has hope, El-Hai shakes his head and immediately says yes. “Time will reveal everything eventually,” he predicts.

For the younger brothers, the answers vary.

“I used to, but no,” Donald says. “For all the people who still do, God bless them.”

“Absolutely,” Tom says. “If they haven’t aged out, I believe my brothers are still alive, and I hope they’re well.”

“I want to believe they’re still alive,” Mike adds. “But as time goes on, I start to lose hope that I’ll see my brothers again before I die.”

Mike, Tom, and Donald have dedicated much of their lives to uncovering the truth behind the disappearance of their brothers, though they’ve never made this story about themselves. “It’s not my personal life story to tell, it’s my family’s story to find my brothers,” Tom says.

Tom eventually had children of his own, and says he kept them close at all times. Mike had a daughter and did everything he could to protect her while she was growing up. They say the sadness their family lives with never left or lessened as time passed.

“We’ve lived through this,” Tom says. “It creates a hole in your life. It feels like something is missing. When your parents have this missing thing, you do, too.”

Donald never had children of his own.

“After seeing what my parents went through, I never even considered it,” he says. “If I ever had children, I was worried I’d have to go through what my parents did.”