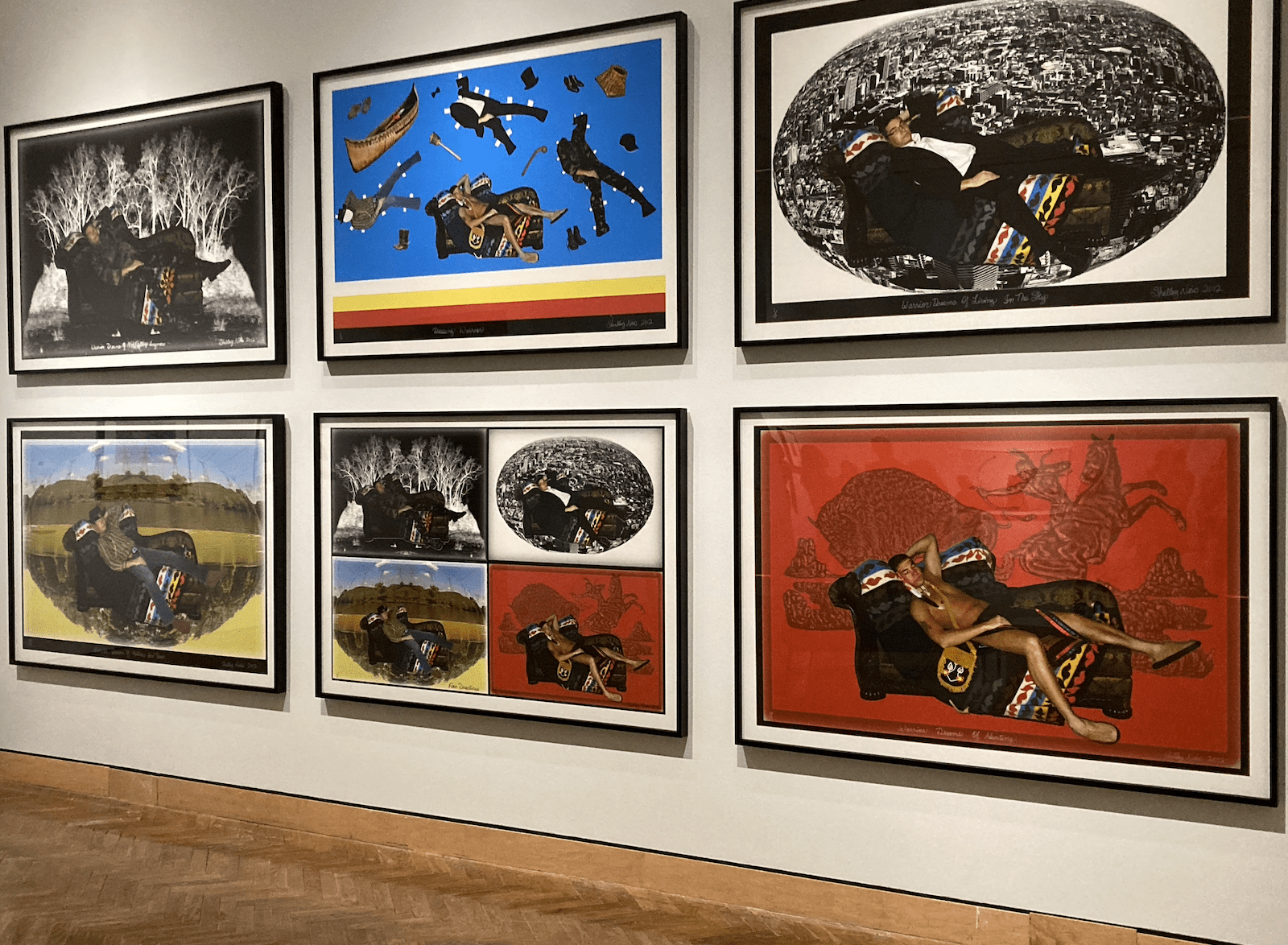

Opening this weekend at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, “In Our Hands: Native Photography, 1890 to Now” is a collection of 150 photographs taken by and for Indigenous people. That shouldn’t be revolutionary, but it is.

“Native people are and have always been more than capable of telling our own stories,” Jaida Grey Eagle, a guest curator and Oglala Lakota artist, said during Thursday's media sneak peek. “As an emerging photographer, I rarely saw exhibitions like the one you are about to see today. I would have benefited greatly from seeing it a long time ago, and I'm glad that it's happening now for the next generation of photographers.”

Planning for the show began in 2019, with Mia staff bringing on a curatorial council of 14, composed of Indigenous artists, community knowledge-sharers, and academics from Canada and the U.S. The pandemic forced them to mostly meet over Zoom, but that wasn’t the only unique aspect of organizing the exhibition.

“It was a democratic process,” said Jill Ahlberg Yohe, the museum's associate curator of Native American art. “And that could be seen as a frightening thing–you may think that there would be factions or that it might be that seven people vote for one thing, and seven people vote for another. Actually, everybody was on the same page.”

That collection includes work by Dorothy Chocolate Carseen, a photojournalist with the women-founded Native Indian Inuit photography Association, who travels to Native culture camps to document practices; portraits by Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie of We’wha, a 19th century two-spirit artist who worked in fiber and pottery; and Zig Jackson’s iconic photo, Indian Photographing Tourist Photographing Indians, Crow Fair, Montana.

While “In Our Hands” is a photography show, not all pieces are exclusively photographic. In some cases photography has been woven into baskets, sewn into clothing, and even repurposed as a diorama. Catherine Blackburn’s But There’s No Scar? uses beadwork on leather to represent a bruise that she wears on her back.

“She is talking about her family healing from the trauma of colonization, particularly boarding schools,” Grey Eagle said. “She uses her traditional knowledge and what has been passed down to her as a gift to heal. That healing is within the traditional work and it comes out in bruises, bruises healing.”

Joi T. Arcand transforms family photography into playful dioramas, recreating mundane moments from childhood into something that looks like a school project, complete with a tiny carebar, wood-paneled walls, mid-century mod furniture, and tiny food.

“She's intentionally calling on these kinds of humble, almost kitschy elements of domestic life,” said Casey Riley, Mia’s chair of global and contemporary art and curator of photography/new media. “And in doing that she's also reclaiming the diorama, which, as we know, is itself a derivative of 19th century practices of museum display where scenes would be recreated… to show the past of different cultures.”

So is “In Our Hands” worth the price of admission? That depends on your budget, but I’d say yes. It’s a thoughtful collection of works from artists, journalists, and activists who aren’t showcased enough. Regardless of whether or not you visit the show, its very existence is an important reminder to always consider who is behind the lens controlling the narrative.

“In Our Hands: Native Photography, 1890 to Now”

Where: Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2400 3rd Ave. S., Minneapolis

When: Oct. 22-Jan. 14, 2024

Tickets: $20; $16 members; find more info here