If Minneapolis teachers go on strike this year, it will be the first time they've done so since 1970. And unlike the last time around, it will be legal for them to do it.

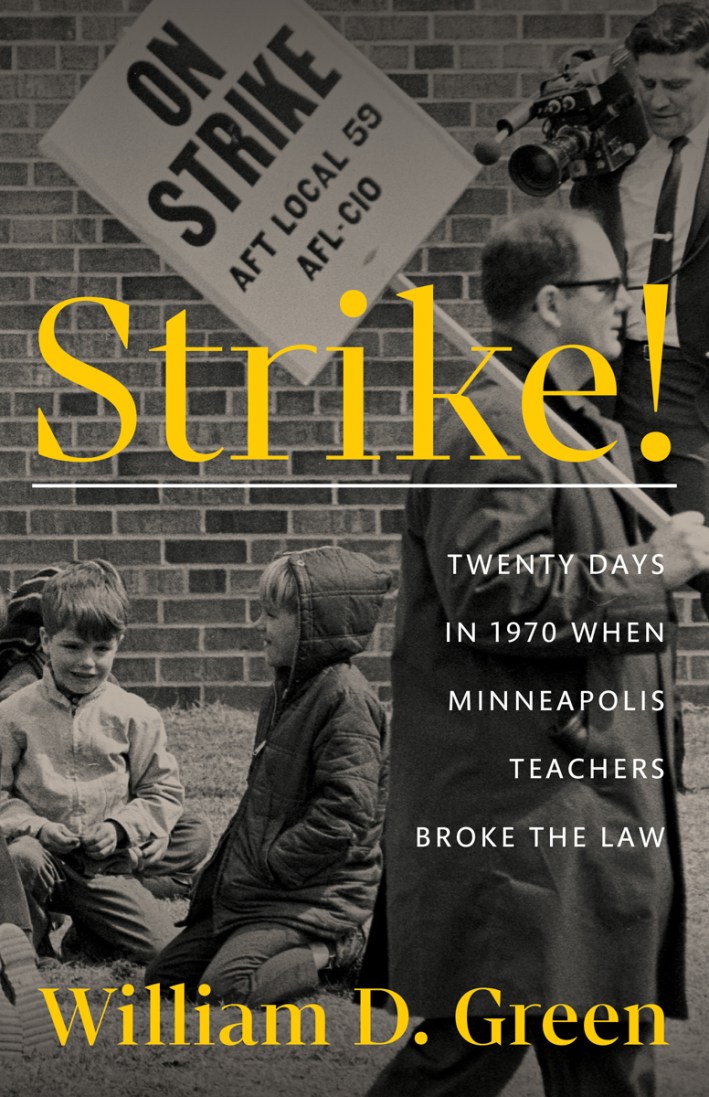

In his forthcoming book Strike! Twenty Days in 1970 When Minneapolis Teachers Broke the Law, historian, professor, and former superintendent of the Minneapolis Public Schools Bill Green takes a look at a watershed moment for labor in Minneapolis and in Minnesota. The legislature had passed a law banning public employees from striking in the 1950s, and in going on strike that April, teachers risked everything: their jobs, their pensions, their futures.

We spoke with Green about the bravery of these teachers and their ultimate victory, which forever changed the city's politics and gave educators the right to collective bargaining.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Racket: Well this has turned out to be quite a timely story you've written here, with potential teacher strikes looming in both Minneapolis and St. Paul.

Bill Green: I remember finishing up the manuscript, talking to my editor, and I was saying, “Do you think this is timely? Do you think anyone will care?” She said, “Well, we’ll put it out there anyway. We’ll see.”

Racket: I have to say, I was looking the 1970 strike up as I prepared for our conversation, and there’s not a lot out there. When I Googled it, the first thing that came up was… your book.

Green: That’s one of the reasons why I wrote it. The impression that people have of Minneapolis—at least used to have, prior to George Floyd—was that the city is very progressive. And to a large extent, it is. The police department and the city of Minneapolis aren’t one and the same. But it is a city that people think they know. And what they think they know is founded on the image of Mary Tyler Moore throwing her hat in the air on Nicollet Avenue. And as a result, I think because people think they know, they think there’s nothing really to learn.

Racket: What else drew you to the story of this strike?

Green: I got interested in this topic because I knew a handful of people that were teachers during that time. What I found interesting about it was the way they reacted whenever I mentioned the strike to them. They had the look of the type of person who was a veteran from combat. They were still wounded, they were still haunted by that moment. And I found that really curious. I had been in unions before, I’ve been on the picket line, I’ve gone through strikes, and I remember when, in my view, the stakes were physically higher. To think that teachers could experience something as distressing as they did really made this moment that much more alluring for me to understand.

Racket: I'm sure it was a really scary thing for those teachers, and we just don't hear too much about it.

Green: Once I got into the strike I began to see all kinds of things that few people really thought about. Most people have heard about the Chicago 8. Most people have heard about Chappaquiddick and the shooting of the kids at Kent State. All of that is happening at the same time. All that stuff is in the headlines. And everybody seemed to be striking at this particular time. Just about every collective group was striking, across the country and in Minneapolis: truck drivers, air traffic controllers, bus drivers.

These became elements to understanding what Minneapolis was about during this strike, what the strike meant. To me, it wasn’t just the strike that was in and of itself noteworthy, but it was the context, it was the times that created a story that needed to be understood. The issue of race is just in the background, just around the corner. The factors that would lead to white flight are during this particular period. There’s a lot of things happening in the city and the state.

Racket: And then on top of all that: teacher strike. Illegal teacher strike!

Green: The teachers were the last bastion of civility and stability. The teachers were the one professional group that most people had contact with. They looked at their teachers as next-door neighbors. And the last thing they expected them to do was go on strike.

In 1970, the MFT, which was the more progressive of the two bargaining unions, gained the majority of the teachers. What began as a labor dispute dealing not so much with wages—that wasn’t a major thing, although it was a factor—was class sizes. Teachers were overwhelmed, 30-plus students in a classroom, lack of equipment, materials. They would ask principals and school board members who would visit the building, “Can you give us some chalk?” I mean, it was that desperate.

Racket: It's interesting that you mention the broader context around the teachers strike in 1970, because it seems like there are parallels today. We're seeing another big labor push here and around the country. It's a tumultuous time politically. Race issues are coming to the forefront.

Green: There are some. It's important, though, to not minimize the impact of COVID on teachers. I don't know enough about what the teachers are dealing with now, but I can say, more than likely, some of the same issues are at play: wages, benefits, quality of life in the classroom, class sizes. But in addition to that is the boogeyman, and it's the pandemic. Teachers today are dealing with parents who are worn out and afraid.

The notion of weaponizing masking and vaccines—that is problematic, because it has turned parents, really for the first time, against their own teachers. Historically, parents and teachers have generally been on the same side. You didn't see parents attacking teachers like you do now. Teachers are only trying to keep kids safe and keep everybody connected in the classroom and the school. And as a result, they're under a lot of stress.

Racket: Can you talk about the teachers you spoke with for the book? It sounds like they were traumatized by it, or maybe traumatized is the wrong word...

Green: That's exactly the way to characterize it. I was talking to teachers in the 1990s heading into the 2000s, so 25 to 30 years had passed, and that wound was fresh—that's what compelled me to get into it. They'd lost a lot of friends. You had teachers in buildings who were with both bargaining units, and it was the circumstance that polarized them from their friends. During the strike, what had been collegial in the building broke apart. The strike was kind of a test of character, too, that resulted in people feeling guilty for some of the decisions that they made.

Some of the teachers recognized that a strike was necessary because they could see that the district did not respond and did not feel like it had to. But by picking up a placard and going on the street, you have automatically lost your job. That's how the law was written. And not just your job, but all of your benefits. You had lost your pension. You'd lost everything. So if you'd been teaching for 25 or 30 years, you were risking everything that you worked for. You have a situation where people are deferring to the impulse to protect, understandably, their own interests. But in doing that, they're kind of letting themselves down. And the thing about picket lines is, you can see who your friends are. No one knew how the strike was going to end; this is all unprecedented. And that exacerbates the tension among the teachers.

Racket: You’re a history professor, you spent four years as Minneapolis Superintendent—did that first-hand experience help you understand this story?

Green: Oh, absolutely. I was chairman of the school board during a time when friends of mine were on the opposing side; I actually had members of the NAACP hang me in effigy! The responsibilities that one takes sometimes compel you to make decisions that will alienate people who were once on your side. I can sympathize with the union bosses—they had to inspire teachers to go against tradition, to go home and see their bank statements dwindle. They had to say, "We're in this together," and they had to keep the spirits and the agenda up. And then you get to the inevitable moment where it's time to resolve this thing. Selling a compromise at that stage is very, very difficult.

Racket: And did they get their demands met, at the end of the day?

Green: They did, and here's the thing that makes that strike historic, in my opinion: They changed the law of the state. They empowered public employees to negotiate with management. That's something that had never been done before. They did the unimaginable. And in a sense, that was much more important than the other issues they were bargaining for. The law that was changed basically placed the state on the side of labor in a way that it hadn't been in the past, whereas before, the state was anti-labor because it kept labor from staking a position and being viewed as equals, as people. There was an incremental improvement over the quality of life—and that's one of the reasons you haven't seen strikes.

Racket: This is all fascinating. I feel like labor issues are one of the defining issues of our time, and it's hard for me to imagine a time when legally, you couldn't strike.

Green: And I cannot underscore this point enough: These are people who had defined themselves as quote "good citizens," which is to say conservative citizens, who did not see themselves as militant or radical or rabble-rousing. When these people, who had invested decades of their lives to an institution and had accrued reasonable retirement funds, benefits, and things of that nature—when they threw it all out to pick up a placard and go to the streets to fight for something like the change of a law, that, to me, means you're talking about a lot of heroes here. Ordinary people acted heroically. That's what the story, for me, is about.