In the late 1980s Rolling Stone was a magazine published biweekly to remind teenagers of our insignificance.

In December 1988, for instance, I learned that I had just lived through “a year without heroes.” This information came from an overview of the previous 12 months written by sour Stone editor Anthony DeCurtis, who did acknowledge that hip-hop was flowering, while himself finding hope for the future in such characteristically DeCurtisian artists as Tracy Chapman and Ziggy Marley. But he couldn't help but lament the passing of what he recalled as the universally shared cultural moment of the 1960s—a time when we all listened to the Beatles together.

The thing is, you know when we all listened to the Beatles together? 1988. Flip just a bit deeper into that same issue—past Robert and Katie Wagner shilling for Sasson, a two-page Columbia House Record & Tape Club spread, and a Polo Ralph Lauren ad – and you can read a news item regarding the Fab Four's induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, an institution created by Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner a few years prior.

The induction ceremony closed with an all-star jam: a stage clogged with several Wu-Tang Clans' worth of drunken middle-aged white superstars milling around with guitars while Paul Shaffer plays the Beatles' “I Saw Her Standing There” on keytar and Ringo Starr stares at his drum kit with the Keanu-like bafflement of a man confronted with an unassembled 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle of a Rothko print. “Well she was just 17,” sings Billy Joel, the youngest old man in the room. Joel's current wife was just seven at the time.

In the late '80s the Beatles were everywhere. The band's catalog was reissued on CD beginning in 1987, timed to coincide with the 20-year anniversary of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, which Rolling Stone had anointed the greatest album of the past two decades in a special issue that summer. In the fall of 1986 the Beatles' version of “Twist and Shout” unexpectedly hit #23 on the Billboard Hot 100 (just above Billy Joel's “A Matter of Trust” and below Cyndi Lauper's “True Colors”), thanks largely to a scene in Ferris Bueller's Day Off where the slappably smug Matthew Broderick lip-synchs the tune to an adoring throng of Chicago parade-goers as a marching band joins in. In a glib act of cultural leveling, an eye-poke to '60s idealists, “Twist and Shout” serves as the encore to Ferris's show-stopping mouthing of the 1963 Wayne Newton hit “Danke Schoen”—why shouldn't Reagan-era families enjoy both rock and pop as harmless “good-time oldies”? (And why shouldn't bow-tied reactionary pundit George Will consider this "The Greatest Movie"?) Yes, in the late '80s the Beatles were everywhere, and among the Boomer faithful one could sense a fear that this very ubiquity might just undermine their lads' special significance.

In 1987, when “Revolution” was licensed for use in a Nike ad, the three surviving Beatles, with significant fan support, rallied against this alleged co-option. The question of who could control and interpret and exploit the legacy of the Beatles resurfaced repeatedly in those days, accompanied always by a desire to protect the band from being incorporated inappropriately into modern culture and commerce. A year later, Albert Goldman published his scandalously revisionist The Lives of John Lennon, right around the same time that Bono famously purported to steal “Helter Skelter” back from Charles Manson on U2's Rattle and Hum. And so, what seemed to teens like me at the time like Boomer triumphalism was, in retrospect, more like a wagon-circled anxiety regarding some indisputably ugly developments in American society. In part, '60s-worshipping rockism was a misguided attempt to combat reactionary politics and the corporate appropriation of culture with idealist nostalgia.

Still, being a teen Beatles fan in the '80s was like trying to eat ice cream while weird older men insisted on lecturing you about the historical significance of ice cream. Those of us born in the baby bust of the Nixon years were a demographic minority. They had the guns, but we had … well, they also had the numbers. And the magazines. And the broadcast licenses. Boomers like Don Henley and Steve Winwood and Paul Simon reclaimed the charts from new-wavers and MTV upstarts by mid-decade, and on TV, teens most served as projections of political anxieties to be neutralized like Alex P. Keaton, or like Theo Huxtable, their easy dupability assured nervous parents of their domestic mastery.

No wonder the punks like Joe Strummer once spat “No Elvis, Beatles, or the Rolling Stones” and told the hippies to piss off. And no wonder kids much cooler than me were inventing college-rock, hip-hop, and all kinds of underground dance music. But what about those of us who thought it an unjustifiable self-infliction of austerity to deny ourselves the pleasures of the past? What about the modern lovers who, to paraphrase Jonathan Richman, still loved our parents and still loved the old world?

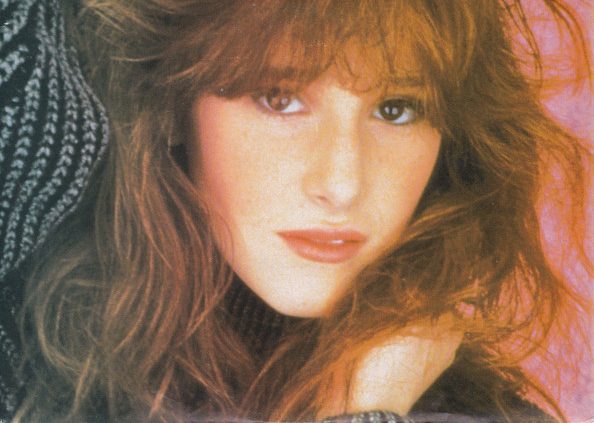

Tiffany Darwish was a redheaded California kid born in 1971 who grew up singing Tanya Tucker and was discovered by Hoyt Axton and his mama Mae, the folks who wrote “Heartbreak Hotel.” They carted Darwish off to Nashville, where she was soon swooped up by former Motown hand George Tobin in 1984. As Tiffany Renee, she sang Jennifer Holliday's “I Am Love” on Star Search and came in second. (Televised singing contests were so unimportant in the '80s they actually let Ed McMahon host them.)

She signed to MCA as Tiffany, but her first single stiffed. So Tobin got creative: The “Celebrating the Good Life Shopping Mall Tour ’87,” which started at the Bergen Mall in Paramus, New Jersey, featured Tiffany singing to instrumental backing tapes while her corporate sponsors courted interested listeners. She became, according to the title of a People magazine story at the time, “Tiffany, the Teenage Mall Flower Who Serenades the Shoppers of America.”

After Tiffany's back-to-back number-one hits—a dance-pop version of Tommy James and the Shondells' heavy-breathing “I Think We're Alone Now” and “Could've Been,” a big ol' regretful ballad that would have left first-place Star Search finisher Melissa Moultire in the dust—even Rolling Stone couldn't ignore her. Susan Orlean's 1988 celebrity profile of the teen singer was called “The Selling of Tiffany.” Because of course it was.

Orlean deftly captures the veal-pen of an existence in which Tobin had encaged Darwish, though the profile could have done more to historicize him as the latest monster in a long tradition of greedy adults wringing the youth out of an attractive and talented child for the sake of our collective pop thrills. “The trip with her is that she could baby-sit for you,” the shameless manager explains breathlessly to Orlean. “She poses no threat to anybody. Not to parents, not to other sixteen-year-old girls.”

“She was only 16 and the themes on the record are very adult themes,” an MCA VP frets elsewhere in the profile, a reminder that at one odd point in time, the music industry was reluctant to make zillions of dollars by selling recordings of teenagers singing about wanting to have sex with other teenagers. But the '80s were strange: Just a few years earlier Senate hearings had been held to determine how to stop Cyndi Lauper from celebrating the fact that girls wank too.

The central dramatic event of the Orlean profile was the singer's first performance with a band at the World’s Valentine Heartbeat Party in February 1988, with Roger Troutman of Zapp, Exposé, Ray Parker Jr., and Regina Belle. To bring it all home, Orlean kicks a little rockist ontology:

“In the odd light thrown from the stage floodlights, Cinderella Castle looks enormous and historic -- it actually does look like a genuine French provincial castle, complete with spiky turrets and embrasures and arrow loops, built in the fourteenth century, instead of what it is: two hundred feet of fiberglass built seventeen years ago. It’s one of those things that looks absolutely real, but it’s not.”

Well, like the man once said, nothing is real. As with Bette Midler playing the Continental Baths, Tiffany's mall tour was just a way to take her music to her most likely fans. But this breakthrough gimmick branded her forever with a scarlet UPC code. And as proof that the thirst for authenticity can be slaked from the shallowest of pools, Debbie Gibson would became the acceptable face of disposable '80s bubblegum, providing hack critics for decades to come with the supposedly complimentary clichés “she writes her own songs” and “classically trained.”

The video for Tiffany's next single, “I Saw Him Standing There,” was shot at the Disney World show Orlean described. Tiffany wasn't the first to flip the Beatles' “her” to “him”: The Supremes tried it in 1964, though their version was unreleased for 40 years, and Lulu cut a particularly lusty swinging London version in '65. But back then the Beatles were just a pop band. In 1988, Tiff was treading on culture-war turf.

“Tiffany renders this classic giddy teen come-on absolutely sexless -- much like the sterile teen-idol pop the Beatles replaced,” complained the 1992 edition of the Rolling Stone Album Guide. “It's possible to hear 'I Saw Him Standing There' as a deconstruction of the Beatles hit, though denatured is closer to the truth: that halftime-show sax riff and diet-soda-fueled pep rally beat are downright awesome.”

Oh, wait, sorry, he said “gruesome,” not “awesome.” Of course. In this review you can hear the anxiety that the Beatles, while too prominent to ever fade from our shared cultural memory, might be incorporated into an anodyne pop history they're supposed to mark a break from. The band's official narrative is one of hard-earned liberation from the indignities and compromises of mere commerce (and from their possessive female fans) to the creative freedom of the studio. Teen idols from Rick(y) Nelson to George Michael to 'N Sync have told themselves this story while trying to get their fans to go along. It's bootstrap capitalist exceptionalism disguised as artistic transcendence.

Rolling Stone was right be afraid: Tiffany did sound dead set on dragging the Beatles back into the marketplace. Though Orlean portrayed the singer as pure product, the persona that emerges through her music is in fact that of the ideal consumer. When she sings “I could see/That before too long, I'd fall in love with him” she doesn't sound like she's lost her heart, but more like she's just found a pair of jeans she'd look great in. In the Beatles' original “I Saw Her Standing There,” Paul McCartney singles one girl out from the shrieking throng, marks her as special, sings to her. Tiffany, singing to other girls, could care less how (or if) her boy standing there feels. She sounds like she just found exactly what she went shopping for at Merry-Go-Round. And she sounds ecstatic.

The way Tiffany appropriates the Beatles oldie isn’t transgressive, a word that suggests an awareness of boundaries and a deliberate crossing to where you don't belong. There's nothing particularly rebellious about recording a song by one of the most popular musical groups in history, just as there's nothing rebellious about hanging out at a mall. Unless the sales clerks hassle you for spending so much time in their store. Unless Boomer Beatlemaniacs start to wonder what gives you the right to sing their song.

To best describe what happened here, I’d like to reclaim a word that’s become an insult. Tiffany's “I Saw Him Standing There” is an act of entitlement, in the way so much great pop expresses entitlement. It’s the sound of hanging at the mall because your suburban existence denies teens any other public space. It's the pop belief that public culture belongs to anyone who can stake her claim. And it hints at a recognition that the refusal of reasonable demands just might encourage us to make unreasonable ones next time.

Back in '88 Tiffany told a reporter how and why “I Saw Him Standing There” was recorded: “[W]e were killing time in the studio and someone picked up an old guitar and started playing Beatles songs. My manager suggested I could do it, and I said, `You`re nuts! No way could I compare to the Beatles.`” And yet what she did with “I Saw Him Standing There” is … way beyond compare. Tiffany's possessive rasp betrays none of that origin story's forced modesty and never questions whether she's worthy. She doesn't sing that Beatles song like she has to earn it. She sings it like she owns it.

This article was adapted from a presentation at the 2015 Pop Conference at the Experience Music Project (now the Museum of Pop Culture) in Seattle.

Tiffany

With: Jillian Rae

Where: Turf Club

When: Thurs, May 19, 8 p.m

Tickets: $30; more info here.