JaNaé Bates doesn’t call herself an activist. The Twin Cities-based minister finds that term too cumbersome to be effective. She prefers “organizer.” In her mind, meaningful political change will come through prolonged interactions with the Black populations she assists in Minnesota, not ad-hoc demonstrations.

Spurred by the 2014 police killings of Michael Brown and Tamir Rice, Bates returned from her studies in Scotland to her native Cleveland, where she began counseling families whose loved ones had been killed by the police.

“There was a lot of marching, a lot of crying, a lot of yelling and despair—rinse and repeat,” Bates says. “And so I find organizing to be the off-ramp to that cycle when communities feel like there's nothing getting done.”

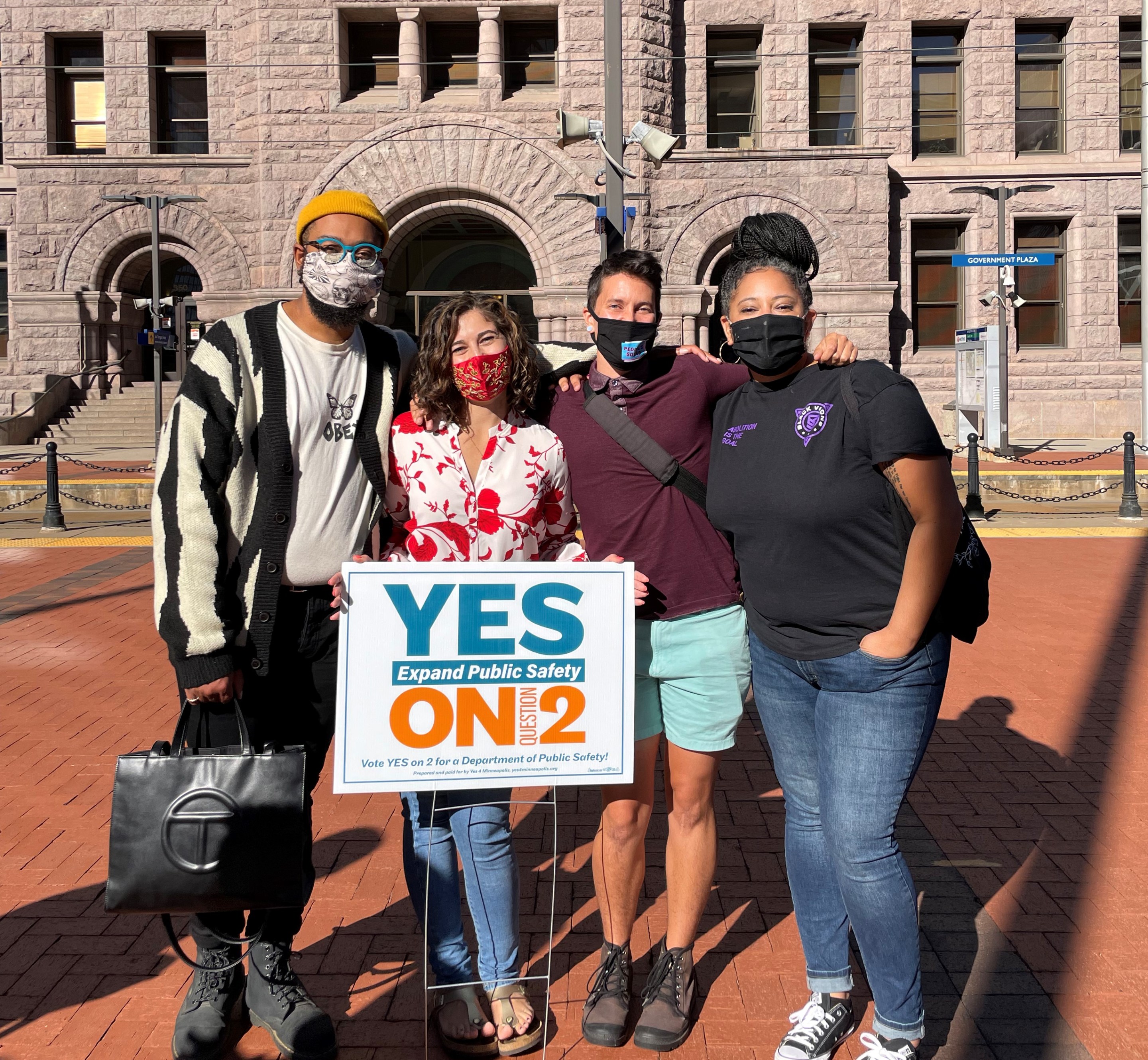

Since the murder of George Floyd last year, Bates and a coalition of Minneapolis grassroots organizations and political advocates have funneled energy into the Yes 4 Minneapolis campaign, which collected 20,000 signatures for a public referendum that would amend the city’s charter and replace the Minneapolis Police Department with a new Department of Public Safety.

According to Bates, who acts as Director of Communications for Yes 4, the amendment would begin the process of moving beyond police-exclusive solutions to public safety. It would give the public additional oversight and transparency, she says, while providing relief from the MPD and its century-and-half long history of brutalizing Black and brown communities.

The referendum will be on the ballot this November.

Bates is part of a growing movement in Minneapolis politics. A collection of new leaders emerged from the ashes of the George Floyd uprising, and they’re fiercely advocating for dramatic police reform, economic justice initiatives, and healthier cities.

Sheila Nezhad is another example.

Nezhad is one of the main challengers to the incumbent Mayor Frey, whose inability to act decisively on the question of police reform inspired her decision to run in the DFL mayoral primary. Should Nezhad win in an upset, the longtime Minneapolis organizer and co-founder of Reclaim the Block—an organization that seeks to allocate police funding to other services—wants to use the potential charter amendment to address the underlying factors that undermine community safety.

At the heart of Nezhad’s campaign: Rerouting resources away from the bloated police budget and into other city services that could help reduce crime, such as adding mental health practitioners in low-income neighborhoods.

“If we invest in solutions at scale, we will see a reduction in crime. But the thing is that we have to invest at the scale that we need,” Nezhad says. “We have enough funding for two teams of two mental health responders. And if there are more than two crises at one time in the city, the police are dispatched.”

Nezhad is acutely aware of how the MPD’s monopoly on public safety enforcement makes creating alternatives to policing extremely difficult—and less democratic. That’s why she was one of the charter amendment’s authors. The Department of Public Safety would be under the jurisdiction of the mayor and the city council, not just the former.

“If I'm mayor, I will make sure the new Department of Public Safety starts with fully funded 911 and 311 dispatch systems, emergency responders that include EMS and mobile mental health professionals, firefighters, domestic violence advocates, and police if necessary,” Nezhad says. “But right now police are required to respond to so many of those things.”

Under the current charter agreement, she points out, even the funds that are reallocated are often crumbs. Launched in 2018, the Office of Violence Prevention, which addresses crime with a community health approach, only receives about 7% of the total police budget—just twice as much as the MPD’s canine unit.

Jason Chavez, the former president of the Minnesota Young DFL, shares many of Nezhad’s views. He’s now running for the Ninth Ward city council seat, and says community security and crime prevention are top concerns among his potential constituents.

Chavez backs the charter amendment, as do social justice-focused city council candidates Robin Wonsley Worlobah (Ward 2) and Aisha Chughtai (Ward 10). Chavez, Wonsley Worlobah, and Chughtai are members of the Democratic Socialists of America’s Twin Cities chapter. All received T.C. DSA endorsements, as did Nezhad, who’s not a member.

“I would say public safety has probably been, aside from housing, one of the biggest issues that come up when we knock doors,” Chavez says. One Lake Street business owner told Chavez he was afraid to call the police when someone apparently under the influence of drugs broke into his store, locking themselves in the bathroom.

“They had two options: Either call the police and things could get really bad, or let it be and this guy might be dying from an overdose,” Chavez says. “And they're really upset because they wanted the resources to know what to do. They wish they had numbers or a dispatch system that can tell them who they can call, someone that isn’t the police that can help de-escalate the situation.”

These progressive challengers are not without their detractors.

Another faction, made up of predominantly older, business-oriented centrists, is skeptical of the charter amendment and its underlying methodology—viewing the strategy as reckless and insisting that “pragmatic” reform is possible.

The faction challenging the charter amendment is spearheaded by Steve Cramer, the President and CEO of the Minneapolis Downtown Council and one-time city council member. He’s joined by a cadre of former elected officials and non-profit technocrats who insist that reforming the MPD—without doing away with the legal standing that separates it from other city departments—is possible.

Somewhat cynically, Cramer implied that the proposed charter amendment would be detrimental to minority-owned businesses, despite Minneapolis already having one of the worst racial wealth gaps in the country. The literature of the “Vote No” campaign also claims that MPD Chief Medaria Arradondo (who opposes the amendment) would lose his job, though by all accounts he would, given his popularity, be reappointed head of police under the new Department of Public Safety.

Many of the solutions proposed by Cramer, Arradondo, and other incrementalists have already been implemented. Following Michael Brown’s killing and the Obama administration’s call for comprehensive police reform, the MPD was equipped with body cameras; they received implicit bias training; community policing strategies were implemented; more police were put on the street. Even with all those reforms, MPD officers remain seven times more likely to use force against Black citizens than against their white counterparts.

“The fact is,” Bates says, “there are people who would call themselves progressive or Democrat or left-leaning and then still say, ‘No, I don't want to do this thing that can protect the lives of Black people. I don't want to do this thing that could… protect the lives of everyone in really beautiful ways because I want to keep the status quo.’”

“The reality is that even saying that ‘I'm too afraid to choose’ is making a choice,” she adds. “And it will put you on the wrong side of history.”

The establishment bloc also insists that there is no actual plan in place. According to Nadia Shaarawi, a longtime police accountability organizer, the implementation of a new Department of Public Safety is not a radical proposition; it’s a concept that has been similarly implemented in more than 20 major U.S. cities.

“If you have something that allows the community to finally have access to changing the structure, it becomes a lot easier to have community control over the new Department of Public Safety, to have actual civilian review,” Shaarawi says, citing the recent creation of a civilian oversight committee by the Chicago City Council.

“We do, in theory, have an Office of Police Conduct Review,” she says. “It used to be civilian-led, but it had no teeth. They added officers to give it more teeth, but now we have cops reviewing the complaints about other cops. And look where that got us: Derek Chauvin had seven complaints.”

Chicago’s push for radical policing changes shares a common thread with the Minneapolis endeavor: It was also advocated for by an ascendant left-wing caucus. The civilian review ordinance was introduced by Alderman Carlos Ramirez-Rosa, yet another DSA endorsee. And in Buffalo, India Walton, an open socialist and tenant organizer, defeated a restrained incumbent in the Democratic mayoral primary. Walton also plans to enact similar approaches as Nezhad, including “a non-law enforcement response to mental health crises.”

Nezhad’s theory of change for the future of public safety is tied directly to her work with The People’s Budget, an initiative that seeks to dramatically reframe the nature of how a city is funded, with working-class and communities of color at the forefront.

“We dreamt it as a community,” Nezhad says. “What would the cities we fund look like? And it was this coalition of radical organizations; it was small businesses; it was big nonprofits; it was unions all coming together. That's the type of coalition building I want to continue, and for me, it's really about not just the power building, but power sharing.”