Over its 107-year existence, the Minneapolis Foundation has accumulated all the essential ingredients for a glossy resume.

The foundation's website reverentially invokes its creation in 1915 by "a lawyer, two lumbermen and two bankers" who banded together to create "a wisely planned and enduring fabric" to benefit the community. It then lists an array of beloved Minnesota institutions and places the foundation has worked to found, preserve, or improve in some manner. From the first federal protection of the Boundary Waters in 1924 to the establishment of the Minnesota Orchestra in 1945 to the construction of the original Guthrie Theater ("A Theater for the People!") in 1963, the foundation claims to have played a vital role. Today, the nonprofit grant-making machine, which boasts annual expenditures of $125 million, is helmed by former Minneapolis Mayor R.T. Rybak.

So when and why, exactly, did the Minneapolis Foundation start trying to kill the Minneapolis Public Schools?

For a dozen years the foundation and its philanthropic allies have focused their money and influence on creating a public school system based on free-market “choice.” The reasons for this are twofold. First, the foundation weakens one of the last unionized sectors in the country, public school teachers; in this case, the same ones who are currently striking for higher wages, smaller class sizes, and increased mental health support. Second, it exposes the billions Minnesota spends annually on public education to private-sector profiteers.

To achieve those goals, the foundation would first flood the city with continuously opening and closing charter schools. Then they would lead a movement to create and fund a raft of dodgy nonprofits to vilify teachers.

Charter Schools: A Minnesota-born Experiment

In fact, if not for the Minneapolis Foundation, there would be no such thing as charter schools. According to Zero Chance of Passage, a book on the start of charter schools by former Minnesota State Senator Ember Reichgott Junge, author of the nation’s first charter school law, they were dreamed up at a gathering thrown by the foundation in 1988 at Madden's Resort in central Minnesota. The posh conference was attended by a “distinguished group of business, education, and civic leaders from around the Twin Cities,” Junge writes.

Although charters today look little like those envisioned by the original proposals, the ideology of the movement still governs: Public schools have to compete for public dollars. Today, of the 180 operating charter schools in the state, five have unionized faculty.

At the time of their creation, many promises were made about the charter school experiment. At first they were to be lab schools, nontraditional learning centers where new education models are tested. Then, proponents said their presence was supposed to make regular public schools better. Then they turned into, essentially, a full-fledged second public school system. The results of the experiment show that charter schools do not get better results on standardized tests, they increase segregation, they put regular public school districts under permanent financial and enrollment pressure, and they have grown a cadre of schools with no teachers’ unions.

Oh, and they fail a lot. By 2008, 16 years after the first charter school in the nation opened in St. Paul, charter schools had yet to gain a significant foothold in the state, and many had already closed for various, predictable problems, such as self-dealing, lack of adequate curriculum, various financial improprieties, and even lack of a building. The classroom environment amounted to “total bedlam,” one student said in a 2005 City Pages story.

In a system predicated as a market, there was no market. In response, the Walton Family Foundation (the Walmart heirs) began funding in 2010, with a lot of help from local foundations, an organization called Charter School Partners, which would funnel the Waltons’ money into charter school startup grants to local entrepreneurs. For charter schools, startup is everything, because, once up and running, the state pretty much pays the bills.

The Calculated Chaos of “School Churn”

At this point, the Minneapolis Foundation was also on a two-tier education track in Minneapolis. It had first tried to influence the district through various initiatives and by getting the district involved with charter schools. In the early and mid 2010s, the foundation had compliant superintendents believing in the wonder of charter schools. But the foundation was also gearing up with another plan in case that tack didn’t pan out: to flood the district with charter school startups.

Charter School Partners, which the Minneapolis Foundation gave $1.3 million between 2009 and 2015, initiated a plan to open 20 new charter schools in Minneapolis. Because school funding follows the students, this plan was a major threat to the Minneapolis Public Schools. Besides the potential loss of funding, the district would face the problem of continuously opening and closing charter schools, with students moving between the two systems in an unpredictable manner.

Charter school advocates call this “school churn,” and have actually embraced it as part of their strategy. This is a big problem for school districts, as a report from Moody's Financial Services noted in 2013. Public districts are institutions that cannot react to that level of chaos. As Moody's wrote, districts are forced to “cut academic and other programs, reducing service levels and thereby driving students to seek educational alternatives, including charter schools."

The Minneapolis Foundation simultaneously began collecting grants from other local foundations and planning a major charter school initiative known internally as the Education Transformation Initiative (ETI). The ETI was envisioned as both a charter school starter/incubator, and as a charter school movement leader.

By 2015, Charter School Partners was involved with at least 16 charter schools in Minneapolis, many of them segregated and with poor academic outcomes for students. The Minneapolis Foundation also finally launched the products of their ETI–the creation of two new nonprofits, Minnesota Comeback, which was to be the leader of their charter school strategy, and Great Minnesota Schools, which was owned by Comeback and would be the entity that actually doled out philanthropic money to charter schools.

As the resources of Charter School Partners were moved seamlessly into Minnesota Comeback in 2015, the Minneapolis Foundation really bared its teeth. Unlike Charter School Partners, the foundation would exercise much more control over the new entity, as stated in its first IRS 990:

“WE REVIEW GRANT APPLICATIONS AND MAKE RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE MINNEAPOLIS FOUNDATION AS TO DISTRIBUTIONS FROM THE FUND THAT WILL BE USED TO MAKE GRANTS TO PUBLIC SCHOOLS, PUBLIC CHARTER SCHOOLS, AND INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS.”

Instead of the CSP plan to open 20 new charter schools in Minneapolis, Minnesota Comeback had a much more ambitious goal: a plan to create 30,000 “rigorous and relevant” (whatever that means) school “seats” in the city by 2025. In practice that support overwhelmingly flowed to charter schools. Nelson Inz, a school board member at the time, told Racket that, “Many of us knew that the real goal was to open more charter schools and to expand existing ones in the city, and that worried us.”

A 2016 Star Tribune story noted that a group of Minneapolis residents and another, unnamed, school board member suspected that “Minnesota Comeback is out to undermine the traditional public school system by replacing it with a vast network of charter schools, like in New Orleans or Washington, D.C.” Al Fan, director of Comeback, waved off the concerns. He told the newspaper, “Our funders have said repeatedly, we don’t care what kinds of schools we are supporting; we just want the best schools for our kids.”

That wasn’t true, as 96% of grants to schools from Great Minnesota Schools, owned and controlled at the time by Comeback, went to charters over its first five years.

The Enrollment Algorithm

In 2017, one year after Rybak took charge of the Minneapolis Foundation, there were already more than 14,000 students in charter schools in the city, and the district itself enrolled about 35,000 students. If you plan to create 30,000 new charter school seats in a district that enrolls 35,000 students you clearly intend to destroy that district.

When asked to comment for a story that alleges the Minneapolis Foundation is seeking to destroy Minneapolis Public Schools, Rybak provided the following:

“Rob, you continue to fall back to a narrative about work the Foundation used to do before I came to the organization. I have raised this point with you before and hope you will pay attention to the work we are doing, not a cartoon of work we used to do.”

He declined to elaborate. Patrice Relerford, a senior director at the foundation, declined to comment on this story.

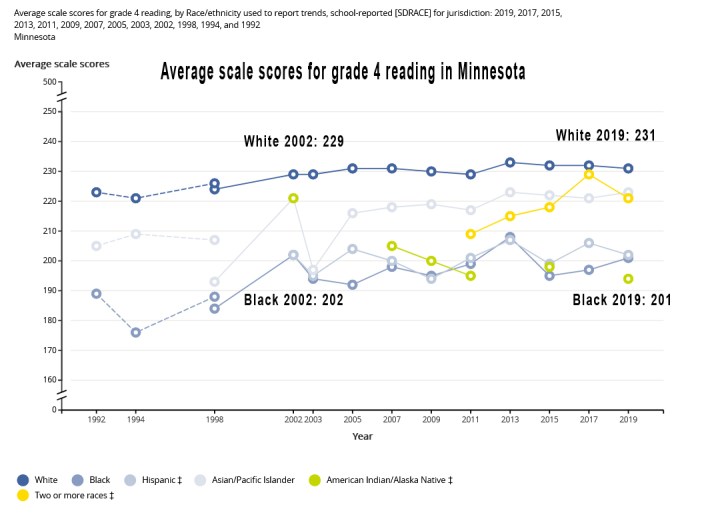

And it's not like the Minneapolis Foundation's ongoing interventions in education policy in Minnesota had borne any educational fruits. According to the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP), creators of “The Nation’s Report Card,” educational attainment in the state has stagnated for 20 years, and so-called “gaps” have remained the same or worsened. For example, NAEP reading scores for Black fourth graders in Minnesota were lower in 2019 than they were in 2002.

Minnesota Comeback failed in 2019 and disappeared into the night, transferring its assets and authority to its previously owned entity, Great Minnesota Schools.

Then, in 2020, the Minneapolis Foundation augmented its educational strategy, quietly creating and funding educational outrage entrepreneurs to pressure the district and public school teachers. That year it gave a $94,000 grant to a group called Ed Allies, an organization that had evolved from another entity the Minneapolis Foundation had helped create called MinnCAN, the recipient of $860,000 from the foundation. Ed Allies was to provide general operating support to a new group called the Minnesota Parent Union (MPU). Whereas MinnCAN was a local affiliate of a national organization, 50CAN, Ed Allies is homegrown.

The Minneapolis Foundation also made a direct grant to MPU for $85,000 the same year, and its created entity Great Minnesota Schools also kicked in with a $30,000 grant in 2020.

"Teachers Unions Destroy Our Children’s Hopes + Dreams"

Just what was the foundation buying with this money? One need only look at the previous Twitter handle of the head of the MPU, Rashad Turner, a former Comeback employee, which read, “Teachers unions destroy our children's hopes + dreams.” His handle now reads, “Teachers’ unions are racist.” But even that level of antipathy toward public schools and teachers wasn't enough for Turner, who later tweeted that Gov. Tim Walz and the state's teachers literally kill children every day.

In Minnesota @GovTimWalz @EducationMN , say Black lives matter when killed by police - they are silent on the Black lives they kill everyday via our education system. Let’s not let them get away with this anymore!

— Teachers’ unions are racist (@RashadsRepublic) May 25, 2021

Last year the Minneapolis Foundation helped create yet another organization to pressure the local district, the Advancing Equity Coalition (AEC). The foundation both provided a grant to the new organization and acted as its nonprofit fiscal agent. Then, over the past year, one of three AEC board members, Sara Spafford Freeman, led a campaign to get the district to fire its superintendent. Why? Because he hadn't solved academic problems in five years that no one, ever, in the U.S. has solved. At the time, another AEC board member was Danielle Grant, who is the longtime CEO of the district's nonprofit partner Achieve Minneapolis, which has received more than $2.3 million from the Minneapolis Foundation over the past dozen years.

The net result of the Minneapolis Foundation's actions regarding the Minneapolis Public Schools can be seen in the drop of its enrollment numbers over the past two decades or so from about 39,000 students in 2005 to about 30,000 in 2021—a decrease of about 25%, even as the population of the city increased by about 12% over those same years. All of this drop cannot be attributed to the foundation, but their actions are a major factor. Coincidentally, the district is blaming declining enrollment as one of the main reasons it claims it can't meet the pay demands of striking teachers.

There's much more to this tale, including the Minneapolis Foundation funding Teach For America in the Twin Cities ($2 million), which puts teachers in front of students after a single crash course. And the funding of KIPP Minnesota ($730,000), whose schools are 93% Black and run by an organization that admitted its pedagogy may have been racist. Or the funding of astroturf groups like Educators 4 Excellence ($1 million), which seeks to counter the authentic voice of teachers' unions, and Students (right!) for Education Reform (now Our Turn, $700,000).

Today, as Minneapolis teachers march through their first strike in 52 years, it's worthwhile examining the state's underfunding of public schools over the past 20 years as a reason for the strike. But it's just as important to understand the other, unaccountable forces that have put the district in a permanent fiscal crisis.