This year, Hennepin County's population surpassed a whopping 1.3 million residents. This vibrant county includes 45 unique cities with diverse ranges of inhabitants and thriving economies. But beyond the hustle and bustle of the present day, lie the traces and memories of Hennepin County's ghost towns. These long-forgotten settlements still offer intriguing glimpses into the past.

Before we jump in, let’s first cover the basics of Ghost Town 101, as there are several different types of abandoned communities. In Minnesota, the first are river towns and trading hamlets, which generally disappeared in the latter half of the 1800s when they were bypassed, failed to be recognized, or made irrelevant by railroads. Railroad towns, in turn, disappeared in the early 1900s when rail lines were abandoned or otherwise failed to grow. Farming, ferry, logging, and milling towns came and went during the 1800s as their local resources were used up or when the economy crashed beyond recovery. One last variety of ghost town—paper towns—never quite made it beyond the drawing board of entrepreneurial real estate investors. Paper towns highlighted the optimism and cruelty of investors hoping to make a quick turnaround in profit from lot sales. Voracious real estate investors left new settlers and lot buyers to deal with losses, which frequently resulted with paper towns.

Of the small villages and towns in Hennepin County that made it beyond the planning stage, many saw lots sold, businesses launched, and churches founded. Even more successful towns supported post offices, hotels, schools, and cultural identities. But early in Minnesota’s history, economic uncertainty and dependency on a single industry caused many early villages and towns to languish. If residents couldn’t sustain their local businesses, they quickly left for greener pastures, leaving behind ghost towns.

All of the towns below went through varying degrees of booms and busts. Some are so desolate that it’s hard to believe that there was so much optimism surrounding them. Once full of life, these small towns now lay abandoned and empty, their stories slowly fading away. You might even live on or near a ghost town, one whose past provides unique insight into the strides and struggles that came with the early years of our state's Euro-American history.

Ghost Towns within Minneapolis

Reyataotonwe was the first ghost town to come and go in Hennepin County. Founded on the southeast shore of Bde Maka Ska, it was settled by Mdewakanton Chief Cloud Man and his tribe of 125 to 150 people between 1828 and 1829. Lawrence Taliaferro, the Native American agent at Fort Snelling, began a farming partnership with the villagers by providing and teaching the community how to cultivate their fields using a farming plow.

The Native Americans referred to their community as Reyataotonwe; whereas Taliaferro coined the village with its anglicized name of Eatonville, after John Eaton, the U.S. Secretary of War from 1829-1831. Euro-American settlers Philander Prescott, Samuel Pond, and Gideon Pond were dispatched to Reyataotonwe in 1834 to assist with farming, cultivating, and education endeavors. The Ponds regarded Chief Cloud Man with immense respect, complimenting that he was “a man of superior discernment and of great prudence and foresight.”

Life in Reyataotonwe was tenuous. There were several skirmishes between the Dakota and Ojibwe near these lands. In 1838, the security of Reyataotonwe fell in contention when Ojibwe Chief Hole-in-the-Day attacked and killed members of the Wahpeton band of Dakota nearby. Upon receiving this devastating news, Cloud Man planned to relocate his village to a safer location further from the Ojibwe.

By 1840, Cloud Man and his tribe abandoned Reyataotonwe. They retreated about 10 miles south to safer lands along the Minnesota River known as Oak Grove (now present-day Bloomington). Gideon Pond also relocated to join Cloud Man and his tribe. The Pond House was built in 1843 roughly a half-mile from the Oak Grove community where it remains to this day.

The Reyataotonwe site was undisturbed until a decade later in 1849. A successful French fur trader known as Charles Mosseaux established a land claim there with permission from Fort Snelling. Mosseaux had been in Minnesota since 1829, working a variety of gigs and odd-jobs. Namely, Mosseaux helped build and paint the John H. Stevens House. Mosseaux was also present during the establishment of Minneapolis on May 11, 1858. In 1857, Mosseaux moved to downtown Minneapolis, which was then a burgeoning milling town. He later sold his plot of land alongside Bde Maka Ska to William S. King, who used it to erect King’s Pavilion.

The next ghost town of Minneapolis was Cheeverstown, named after William Cheever. Cheever was the second Euro-American settler on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River in what would later become Minneapolis. Cheever made a land claim in 1847 that now encompasses the Prospect Park neighborhood and a portion of the University of Minnesota’s campus. Cheever had his hand in many different trades; he was an entrepreneur, farmer, carpenter, and real estate investor. A few years after Cheever settled his land, he hired a surveyor to plat the property into parcels available for sale. Cheever’s small community quickly grew to 300 settlers. Formally, Cheever’s town was platted and recognized as St. Anthony City, although most colloquially referred to it as Cheeverstown.

To propel his town’s economy, Cheever built a ferry landing on the bank of the Mississippi approximately where the University of Minnesota Boathouse is currently located. This landing was known as Cheever’s Landing, which served as a vital port in the early years of settlement as countless ferries unloaded their human and cargo freight.

In 1853, Cheever built Cheever’s Tower on the site that later became the University of Minnesota’s Wulling Hall. The tower was a wooden structure 90 feet tall, 24 feet square at the base, and eight feet square at the observation deck. The lower story of the tower was home to a saloon and an ice cream parlor; whereas the precipice of the tower was outfitted with a telescope which offered commanding views of St. Anthony Falls and the surrounding countryside. On clear days, one could see as far as Pilot Knob in Eagan and Dayton’s Bluff of St. Paul. A painted sign hung at the base of Cheever’s Tower reading “pay your dime and climb.”

John H. Stevens recalled that Cheever’s Tower was an impressive local attraction:

“It is the most conspicuous object for a great distance in every direction. The bend of the river brings this tower directly opposite the face of the falls, about half a mile distant, giving an unsurpassed view of the rapids and cataract and an immense extent of country in every direction forming one of the most varied, charming and extensive landscapes in Minnesota.”

Opposite from Cheever’s Tower were plans for a massive hotel, also under Cheever’s ownership. Finished in the early 1850s, Cheever’s hotel was a three-story, brick-laden wooden structure with 127 rooms and a ballroom, according to its planning documents. In actuality, the hotel was likely much more modest than that.

Cheeverstown faced immediate competition from its inception. In 1849, Franklin Steele and Pierre Bottineau, two successful landowners to the north of Cheeverstown, worked together to plat their City of St. Anthony. Whether out of spite or aggressive competition, Steele and Bottineau omitted Cheever from their plans. Confusingly, for a short while in the 1850s, maps depicted both the City of St. Anthony and St. Anthony City.

It quickly became apparent that Steele and Bottineau’s St. Anthony was developing into a more successful town than Cheeverstown. Its proximity to mills and places of business drew a larger population to St. Anthony than Cheeverstown could muster. When Franklin Steele’s plans were unveiled in 1854 to link the West Bank to the East Bank of the Mississippi via the first Hennepin Avenue Bridge, Cheever’s dreams of pioneering a successful town were squandered. Whether in defeat or seeing it as a new opportunity, Cheever ceded 25 acres of his town to the regents of the University of Minnesota in exchange for $6,000 in 1854. This transaction was the final nail in the coffin for Cheeverstown.

In 1855, Minnesota’s Territorial Legislature incorporated Steele and Bottineau’s City of St. Anthony, which boasted a population of roughly 1,000 settlers. This incorporation act failed to recognize Cheeverstown, which was neither established nor recognized by the legislature. Cheeverstown failed to develop as St. Anthony soared into relevancy, with the remaining residents abandoning Cheeverstown for the new city just to the north. Cheeverstown’s lands later merged with Minneapolis in 1872 along with the City of St. Anthony.

The last ghost town of Minneapolis was roughly three and a half miles southeast of downtown Minneapolis along the Mississippi River. It was known as Falls City. A relative latecomer, it was platted just a year before the incorporation of Minneapolis 1857 by landowner H. C. Keith. Keith’s Falls City was a paper town that stretched from the Mississippi River to 31st Avenue S. The town’s northern border was E. 24th Street; its southern border was E. Lake Street.

Falls City was a result of rampant claim staking on Fort Snelling’s lands during the 1850s. During these years, desirable locations throughout what would become Minneapolis were claimed by Euro-American settlers hoping to make a profit on the platting and selling of land parcels. While many of these early settlers were driven out by Fort Snelling soldiers, Keith managed to keep his lands. When Minneapolis was incorporated in 1858, Keith ceded his plans for Falls City, opting to join his land with Minneapolis. For a few years after the incorporation of Minneapolis, Falls City remained on maps.

Lake Minnetonka’s Ghost Towns

Prior to its vacation and summer destination heyday in the late 1800s into the 1900s, Lake Minnetonka and the surrounding lands were known to the Mdewakanton Dakota as Minnetonka—or “big water." The land was heavily forested and prime for fishing, hunting, and lumber milling.

By the mid 1850s, small villages and communities such as Excelsior, Wayzata, Lake Park (now Tonka Bay), Spring Park, Mound, and Crystal Bay started popping up along the shores of the lake. These villages were settled for their proximity to forested land, suited for lumber and milling operations. After the U.S. Civil War ended in 1865, the industry in this area quickly shifted to hospitality as hotels and resorts opened their doors. However, for one reason or another, several villages around Lake Minnetonka never grew past their infancy. As a result, several ghost towns now hide in plain sight among the wealthy neighborhoods that now surround the lake.

The first of these ghost towns is the former village of St. Albans. St. Albans was platted by two settlers in the region in 1855, about one mile to the east of Excelsior on the eastern shores of St. Albans Bay. St. Albans appeared to establish itself as a successful little village as several businesses, dwellings, and the Trinity Church of St. Albans were built. The St. Albans Inn opened in 1856, constructed by John McKenzie, who himself founded a now-ghost town (but more on that later). St. Albans largest employer was the village sawmill.

St. Albans was ultimately doomed by a series of events that crippled the village’s chances of establishing itself as an economic center in the county. The first blow occurred during the nationwide economic recession known as the Panic of 1857. A majority of the villagers lost their savings in the floundering economy. Many settlers left St. Albans to the neighboring Excelsior, where jobs were more plentiful. The final blow for St. Albans came in 1859 when the village sawmill burnt down. Its destruction resulted in the remaining workers and townsfolk moving away.

The failed proprietors of St. Albans were required by the government in 1860 to produce evidence that their village survived the recession in order to attain city status. However, the townsfolk had all but abandoned St. Albans. A surveyor, dispatched from Minneapolis, was shown to the only remaining home in St. Albans by the town founders. They then took the surveyor into the woods a short distance, zig-zagged their path a few times, and brought him to house number two. This act was repeated several times until six homes were visited. Except there was only one house left in St. Albans. The founders tricked the surveyor into showing him the same house from six different vantage points. Thus, the surveyor believed St. Albans was a successful village as it was granted the status of a city although none of its inhabitants remained. This type of deceit and trickery was a frequent occurrence in many of the ghost towns of Hennepin County.

A second ghost town on Lake Minnetonka was Tazaska. The town was first recognized by the Territorial Congress of Minnesota on May 23, 1844, although it wasn’t platted until a decade later in 1855 on an isthmus between Forest Lake and the North Arm of Lake Minnetonka in present-day Orono. Tazaska only existed for a few short years as the settlement was scrapped during the Panic of 1857; it never boasted enough settlers to attract a post office or school. Tazaska has since vanished from both maps and memory.

A third ghost town on Lake Minnetonka was William Russell’s Island City. Russell selected the location for Island City in 1854 on the western shore of Crystal Bay, just north of the present-day neighborhood of Navarre and east of Lord Fletcher’s Old Lake Lodge. Russell yearned for the Minnesota Territorial Legislature to grant his plat with city status, but approval never came from the government. Island City faded to memory as the rest of Lake Minnetonka boomed.

Yet another ghost town on Lake Minnetonka was Minnetonka Centre. This town was platted at the furthest western extent of the lake, where Six Mile Creek flows into Halsted’s Bay. A few settlers arrived to find that the lands they were promised as fertile were mostly unfarmable marshland. Minnetonka Centre is a prime example of a paper town, as those who purchased lots were burdened to relocate once more. Many moved nearby to German Town, which later reorganized as Minnetrista.

Ghost Towns Along the Minnesota River

Another popular region of settlement in Hennepin County was along the Minnesota River in the southern reaches of the county. Successful settlements such as Shakopee, Chaska, and Carver proved profitable for river trading. Thus, a few entrepreneurial settlers came with hopes to found their own river towns that could compete with the likes of the larger communities upstream. The first of these ilk in Hennepin County was Hennepin Village, located at a bend in the Minnesota River just to the southeast of present-day Flying Cloud Airport. Hennepin Village was formed by John McKenzie, who also laid a helping hand in building the St. Albans Inn along Lake Minnetonka. McKenzie claimed a sizable tract of land along the Minnesota River in 1852. Working with Judge Alexander Wilkin—who was then secretary of the Territory of Minnesota—McKenzie hired Joseph A. Chase to plat Hennepin Village on May 18, 1854.

After Hennepin Village was incorporated, McKenzie built a small hotel near the river’s edge. A grist mill, blacksmith, sawmill, and a number of modest dwellings joined McKenzie’s hotel in Hennepin Village. The village had a brief boom as it served as an important shipping point for grain, people, and goods. Like many of the ghost towns in Hennepin County, Hennepin Village floundered during the Panic of 1857 as families in the small village relocated to more prosperous towns in the territory. The town’s fortunes worsened when McKenzie’s relationship with several of the farmers in Eden Prairie soured. The farmers opted to take their grain crops to other shipping outlets, which further harmed Hennepin Village’s economic output. In a detrimental blow to the village’s hopes of survival, the hotel burnt down in 1867. When Eden Prairie received railroad service in the 1870s, the railroad companies chose to bypass Hennepin Village, thus killing its chances for survival.

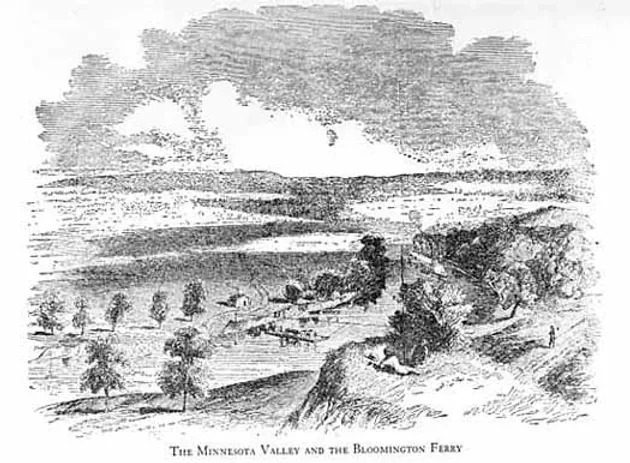

About three miles downstream from Hennepin Village is another defunct townsite, Bloomington Ferry. In 1852, settlers Joseph Dean and William Chambers began construction on a levee where they could operate a ferry service to connect the south bank of the Minnesota River with the north bank. In 1853, their ferry service opened for business. Beside the ferry operation was a townsite bearing the same name that was platted in 1855. To accompany the town, a hotel with a post office and general store was built by Albee Smith that same year. The hotel saw modest patronage, but the town refused to grow into anything of substance due, in part, to its being located in a flood plain. In 1892, the Bloomington Ferry Bridge was completed, which ended the ferry business at the site. The Bloomington Ferry Hotel was destroyed by a fire in 1905.

Ghost Towns Along the Crow River

The Crow River serves as the northwest border of Hennepin County beginning to the south of Rockford and extending to the Crow's confluence at the Mississippi River in Dayton. During the 1800s, this region of Minnesota was encompassed by a large forest known as the Big Woods—or Coteau de grand Bois. While several townsites and villages flourished along the Crow River, the towns listed below weren’t so lucky.

In 1855, the first ghost town on the Crow River, Greenwood City, was established. Greenwood was situated in the far-western reaches of Hennepin County, where the South Fork and North Fork of the Crow River converge. Greenwood’s location was selected by four Euro-American traders who were familiar with the area after trading expeditions with local Native Americans. These men chose the townsite after surveying a nearby series of rapids powerful enough to turn a water wheel for milling operations. The first settlers of Greenwood began to clear the heavy woods to create several gridded blocks with wide dirt streets. The first structure built in Greenwood was a hastily constructed shelter using the felled timber. Once the clearing projects were completed, Greenwood was advertised in newspapers across Minnesota as the most fertile part of the Minnesota Territory with plentiful timber available for harvesting.

By 1856, some 40 families moved to Greenwood after the Minnesota Territorial Legislature passed an act incorporating Greenwood as a city. The town began to flourish with businesses such as the John Burt General Store, The Beaver House & Hotel operated by Albert Laisey, a post office, school, a plethora of carpenters, and a blacksmith. Greenwood was initially successful until, like other towns, it was met with the Panic of 1857. Plans to build a sawmill and to connect Greenwood to Chaska via a new territorial road were scrapped while the nation’s economy nosedived. The population sharply declined from its peak of 76 citizens. To complicate matters further, the nearby town of Rockford quickly surpassed Greenwood in size and economy viability.

By 1860, the town’s buildings remained but the residents had mostly left. Greenwood saw a brief resurgence in 1862 during the U.S.-Dakota War. Settlers from the nearby countryside flocked back to Greenwood for protection when the Beaver House & Hotel was repurposed into a satellite fort and military stockade. After the war ceded, Greenwood slowly faded away. By 1869, the Greenwood Post Office closed. Greenwood’s remaining settlers left after railroads bypassed the city, opting instead to run through Delano to the south and Rockford to the north.

Despite Greenwood’s disappearance, its namesake lived on as Greenwood Township while the farmland surrounding its old borders was organized in 1858. In 1956, the name Greenwood was borrowed and reused for the newly incorporated city of Greenwood near the former townsite of St. Albans. To avoid confusion, Greenwood Township in turn changed its name to Greenfield Township, which remains to this day.

About a dozen miles to the northwest of Greenwood City along the Crow River is the ghost town of Hassan. In the summer of 1855, Harvey S. Norton surveyed the land around a horseshoe bend in the Crow River. After determining that the river’s water power was plentiful enough to support milling operations, Norton suggested that a village be founded in the land immediately surrounding the riverbend. Norton hired a surveyor who platted the town that Norton named Hassan.

Hassan never took off and remained as a paper town. The name was later borrowed on April 3, 1860, as a township organization was created with the same name. The next year, in 1856, the Hassan name was borrowed again for the establishment of a post office about two miles southeast of the townsite near the current intersection of Territorial Road and Hassan Parkway. Septimus Parslow, a man whose name feels ripped from Harry Potter, was appointed as postmaster of Hassan.

Not far to the northeast of Hassan along the Crow River was the paper town of Waterville. Waterville was created as a town site by Charles Aydt in 1854. The town never came to fruition; it was considered too near to Dayton, thus when it came time to select locations for a post office and schoolhouse, Dayton won out and Aydt’s ideas for Waterville squandered.

The Ghost Towns within Medina, Corcoran, and Independence

This area of Hennepin County was opened for settlement just before the Euro-American discovery of Lake Independence. A St. Anthony Express article on March 24, 1855, stated:

“On the north side of Minnetonka Lakes is a level tract of country some ten miles in extent that is covered with black and white walnut and the sugar tree with rich, deep soil and streams of water running in different directions… This spot has been selected for a Quaker colony who are here on the first boats from Indiana… There are two families already on the ground waiting with impatience for the arrival of their brethren. They are far away from civilized communities and have to spend many lonely hours but ‘ere another winter rolls around they will no doubt have schools, stores, meeting houses, and all the advantages of a thickly settled neighborhood.”

One of the first settlements from this Quaker colony was the ghost town of Perkinsville, a small farming town founded in 1857 on the southern shore of Lake Independence by brothers John and Needham Perkins. It’s important to note that Perkinsville was the start of Euro-American settlement in the area, but the area was long known and frequented by Native Americans. (Broadly speaking, that fact is true everywhere Minnesota.) The same day that Lake Independence was "discovered," an abandoned Native American cabin was found on the southern shore of the lake. Native American burial grounds were found on the southeast and northern shores of the lake, and Lake Independence’s island was noted for its plethora of Native American artifacts.

When the Perkins brothers settled the area, they each built wooden homes. Needham Perkins built a sawmill and small general store. Perkins’ sawmill was accompanied by Job Moffitt’s sawmill, which was erected the same year at Lake Independence’s outflow at Pioneer Creek. Perkinsville saw quick development as a colony of several families from Indiana arrived. The two founders built the Lake House Hotel, which was frequented by summertime guests. The town was also home to many modest dwellings, a schoolhouse, general store, blacksmith, post office, and a brick-making business.

The Panic of 1857 paired with a grasshopper infestation wreaked havoc on the fledgling community’s farming operations. Perkinsville managed to survive the economic downturn, but the town never reached prosperity. The St. Paul & Pacific railroad bypassed Perkinsville in favor of Maple Plain in 1868. Thus, the dream of Perkinsville becoming a bustling community collapsed as it became a shadow of the once-ambitious Quaker settlement. The Perkins family eventually moved to Maple Plain, with many of the townsfolk following suit. The only signs left of Perkinsville are a few scattered broken bricks from the kiln that get churned up when the fields of the ghost town are tilled, and the aptly named Perkinsville Road on the south shores of Lake Independence.

To the south of Katrina Lake, near the border of Medina and Orono, lies another ghost town called Cumberland. Cumberland was founded by George Knettle in 1857 after the Minneapolis & Fort Ridgely Territorial Road was laid through this section of Hennepin County. Nettle built a steam sawmill on Painter Creek, where he also erected a farm and guest house called the Cumberland House. Two other settlers, Darius A. Keyes and Frank Fleming, built houses within Cumberland. A few families came and went from the community, but the population likely never exceeded 30 residents. That was the extent of Knettle’s “City of Cumberland,” which was never formally recognized by the state government. Cumberland’s last mention came in 1862 during the U.S.-Dakota War when the Cumberland House was repurposed as a safe house for Euro-American settlers. Although never mapped nor platted, Cumberland was likely near the intersection of Watertown Road and McCulley Road in present-day Orono.

The last ghost town in this area was Burchsville (sometimes mapped as Brushville), a forgotten hamlet that was situated near the intersection of County Roads 10 and 19 in present-day Corcoran. The land for Burchsville was made available by the Weinand family in the 1860s for development, but few settlers ever purchased lots and the town never blossomed. In 1894, the one-room Burchsville School was built and would remain in operation until 1967; it has since been turned into a museum.

It’s not surprising that there are a plethora of ghost towns in this area of Hennepin County. As the region was opened for settlement, many entrepreneurial homesteaders created villages with the optimism that they could generate enough buzz to attract business and propel their properties into relevancy. Although many of these little villages didn’t last, some remain and thrive today: Hamel, Loretto, Long Lake, and Maple Plain among them. Others, like Armstrong, Fletcher, Ditter, Lyndale, and Leighton, still exist in name only.

The Ghost Towns up the Mississippi River

North of what would become Minneapolis along the Mississippi are a trio of ghost towns within present-day Brooklyn Park. These sites were selected for their proximity to lumber, clay, and water resources, and they'd remain until resources and business prospects ran out.

The first of these villages was Industriana, a lumber milling and river town on the West Bank of the Mississippi River, located about 11 miles north of downtown Minneapolis. Industriana came to fruition in the mid-1850s, when The Industrial Mill Company formed by J. C. Post was launched. Post platted a town surrounding his millsite, thus Industriana was born as a successful lumbering center of the 1850s. A few brick kiln businesses kicked off after a vein of red brick clay was discovered on the banks of the Mississippi within the town’s limits.

The sawmill at Industriana was a large operation and had just started to turn a profit when disaster struck. On November 10, 1858, Industriana found itself plastered in newspapers across the state after a horrific boiler explosion occurred at the Industrial Mill Company. Seventeen men were tending to the mill when one of the three boilers burst. Noise from the explosion was reported as far away as Minneapolis. One of the two-ton boilers was allegedly blown nearly a quarter-mile away; the adjacent boiler was sent flying through the air, eventually lodging itself in the opposite bank of the Mississippi. Several employees were severely injured from the accident, which saw the closure of The Industrial Mill Company. As a result, Industriana drifted into irrelevance as the main employer of the town folded. By 1911, the few old-time houses left in Industriana were torn down.

About a mile north of Industriana was another, smaller hamlet known as Warwick, a pipedream from Thomas Warwick of St. Anthony via Maine. Looking to set up a sawmill business, Warwick spent his first year in Minnesota staking a claim along the Rum River and, later, the St. Croix River before finally settling along the Mississippi River in 1853. That same year, Warwick attempted to incorporate the town named after himself along the Mississippi with the Minnesota Territorial Legislature. For whatever reason, the territorial government refused to grant Warwick with city status. However, the government permitted a post office to be established in would-be Warwick, which is the only remaining structure in the ghost town off of West River Road. At the time of Warwick’s passing in 1903, his settlement had mostly been forgotten. Warwick and his dreams to create a modest city were buried in Mound Cemetery in present-day Brooklyn Center.

The last ghost town up the Mississippi from Minneapolis in Hennepin County is Harrisburg, which came on the scene in 1856 when the Harrisburg Sawmill was erected on the West Bank of the Mississippi River. Harrisburg was located to the north of the present location of the Hwy. 610 Bridge. The townsite was platted on 160 acres with several homes, a hotel, and a general store. The Harrisburg Post Office was opened in 1858 with Postmaster Cyrus Helliman at the helm, yet another postman with a great name. Harrisburg, like many of the other ghost towns, was entirely dependent on its milling industry. By the 1860s, the Harrisburg Mill closed after failing to keep relevant with competition in Minneapolis. The Harrisburg Post Office quickly followed suit, closing in 1873. The next year, two of the abandoned Harrisburg homes were found engulfed in flames. Prompted by further fire fears, the remaining houses and buildings were razed in the 1870s.

Other Ghost Towns in Hennepin County

There were two more ghost towns I found while researching this subject. The first of them is Farmersville. Farmersville was in the northern portion of Crystal Lake Township, where it was set apart by county commissioners on July 8 1858. The town’s location was described as follows:

"Beginning at a point on the Mississippi River, at the south line of section 12, township 118 north, of range 31 west of the fifth principal meridian; thence west to the southwest corner of section 7, township 117 north, of range 21 west of the fifth principal meridian; thence east to the Mississippi River; thence up said river to place of beginning."

It took way too long to research this, but I found the actual map that was referenced to compare Farmersville’s location with present-day features. Farmersville’s southern border was 45th Avenue N. starting at the Mississippi and heading westward to Hwy. 169. From there, the town border turned due north to 53rd Ave. N. The townline then jogged eastward back to the Mississippi River. Anyway, Farmersville only lasted for a few months. In the subsequent town meeting, its incorporation was reconsidered and its lands were ceded back to Crystal Lake Township.

The last ghost town I learned of was Attraction. Attraction was platted in 1856 by settlers Warren Sampson and Isaac Labosiniere just to the southeast of Osseo. Osseo was a portion of Maple Grove Township, whereas Attraction was within Brooklyn Township. After a few years of existence, the city commissioners of Osseo absorbed Attraction in 1875 due to its close proximity. The only noticeable remnant of the City of Attraction is 1st ½ Street in Osseo. This street was the northern terminus of Attraction. When Osseo annexed Attraction, they had to form their city grid around Attraction’s slightly off-canter blocks.

It’s truly fascinating that there were once so many towns battling and striving for relevancy during the early years of Hennepin County’s history. The heyday of these towns have long since passed, but their stories remain, shrouding these former communities in captivating drama. They serve as important reminders to appreciate the history that has shaped the state we live in today.

This story originally appeared on The Minnesota Historian, the local history website run by Josh Biber.

Sources

- O’Brien, Frank G. “Various Changes Which Forty Years Bring” The Minneapolis Tribune, December 24, 1899. P. 30.

- “Festivals in the Country” The Minneapolis Tribune, June 14, 1870. P. 4.

- Frear, Dana. “Ghost Towns of Hennepin County” Hennepin County History, Winter 1963.

- Frear, Dana. “Background of the Settling of St. Anthony” Hennepin County History, Fall 1960.

- Buechner, Louis; Cook, R. “Sectional Map of Hennepin Co. Minnesota, Showing Cities, Townships, Townsites, Roads & Rail Roads” Hennepin County Digital Library, 1860. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll17/id/124/rec/10

- Dahl, P. M. “Plat Book of Hennepin County Minnesota. Compiled and Drawn from Official Records and Actual Surveys.” Hennepin County Digital Library, 1898. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll17/id/5903/rec/17

- Pottle, James M. “Jas. M. Pottle's Addition to the Town of Harrisburg” Hennepin County Digital Library, 1857. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll17/id/3646/rec/22

- Wright, George B. “Map of Hennepin County, Minnesota. Plate 27 - Brooklyn” Hennepin County Digital Library, 1873. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll17/id/5839/rec/50

- Stubbs, Avery. “The Quaker Settlers from Ohio and Indiana” Hennepin History, Summer 1850.

- Perkins, John B. “Map of Perkinsville” Hennepin County Digital Library, 1857. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll17/id/3720/rec/3

- Olson, Gail. “Archaeologists, Historians Evaluate Artist’s Riverbank Artifacts” Northeaster, November 17, 1997. P. 7.

- Wallof, William. “The Side-Wheeler Saint Paul at Cheever's Landing on Mississippi River” Hennepin County Digital Library, 1904.

- Zalusky, Joseph W. “Patentees: Some Interesting Highlights and Some Prominent Names” Hennepin County History, Spring, 1962.

- Flanagan, Barbara. “We’re Lively, but We’ve Got Ghosts” The Minneapolis Star, June 10, 1971. P. 1C.

- Von Sternberg, Bob. “Ghost Towns” Star Tribune, February 5, 1989. P. 1.

- “Continuation of the History of St. Anthony” Minneapolis Weekly Times, September 20, 1856. P. 2.

- Smith, Herman C. “Tazaska” Hennepin County Digital Library, 1855.

- “Greenwood, Hennepin County” Minnesota Weekly Times, April 5, 1856. P. 2.

- Thomas, Jane. “Lake Discovered 100 Years Ago Today” The Minneapolis Tribune, July 4, 1954. P. 33.

- Edgar, Randolph. “Minnetonka Mills, Unheeded Now by Motorists, Once Minneapolis' Rival and a Steamboat Port” The Minneapolis Tribune, June 28, 1925. P. 21.

- O’Brien, Frank G. “Various Changes Which Forty Years Bring” The Minneapolis Tribune, December 24, 1899. P. 30.

- Thompson, Ruth. “Cheever’s Guests Paid Dimes to View Falls” The Minneapolis Tribune, September 19, 1949. P. 6.

- Davies, Pearl Janet. “Site of Cheever Tower” The Minneapolis Tribune, September 21, 1919. P. 42.

- Young, J. H.; Hazard, J. L. “Map of the Organized Counties of Minnesota” Hennepin County Digital Library, 1850

- “Greenwood/Greenfield History” Greenfield Historical Society, 2015.

- Neill, Edward D.; Williams, J. Fletcher. “History of Hennepin County and the City of Minneapolis, Including the Explorers and Pioneers of Minnesota” North Star Publishing Company, 1881. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL23304586M/History_of_Hennepin_county_and_the_city_of_Minneapolis

- Hopkins, George E. “Bloomington Historical Sites” Hennepin County History, Fall 1970.

- “The Minnesota Valley and the Bloomington Ferry” Minnesota Historical Society, May, 1857.

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. "View of St. Anthony, Minneapolis and St. Anthony's Falls. (From Cheever's Tower)." The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1857. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7da3-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99